Joan (John) Baez with her guitar

Capturing Beauty

On this day, October 25, 2025, I went searching for a true name for Hippie. a name we hated, that was thrust upon us. I found….

PRINCE FLEURIMOND

Prince Fleurimond falls in live with Princess Rosamond. Did they have a child? Was thus chid…….A FLOWER CHILD?

The name of this child is….

FLEURI

We are……The Vleuri.

John Presco a.k.a.

JON FLORIMOND

Florimond is a masculine name with Latin and Germanic roots, meaning “blooming” or “flowering” and “protection”. It is a male name, sometimes spelled Fleurimond, with origins in ancient Germanic and Latin languages.

- Meaning: The name combines the Latin “florus” meaning “blooming, flowering” with the ancient Germanic element “mund,” which means “protection”.

“Wake up, Jeff.” — Joan Baez suddenly announced that she would pull all of her music and collaborations from Amazon, criticizing Jeff Besoz.

Prince Florimund is the male lead in the ballet The Sleeping Beauty, who awakens Princess Aurora after she has slept for 100 years. In the second act, he is introduced as a prince on a hunting expedition who is guided by the Lilac Fairy to the sleeping princess, whom he first sees in a vision and falls in love with. He then travels to her palace and breaks the curse with a kiss.

Rosamond is a name for the princess in the Brothers Grimm’s version of “The Sleeping Beauty,” though other versions use names like Briar Rose or Talia. In this version, a curse by an uninvited fairy causes Rosamond to prick her finger on a spindle and fall into a 100-year sleep, along with her entire castle. The curse is broken when a prince finds and kiss.

“Wake up, Jeff.” — Joan Baez suddenly announced that she would pull all of her music and collaborations from Amazon, criticizing Jeff Bezos’ quiet alignment with Trump. The statement quickly became an ultimatum that stunned both Bezos and the public.

“You support Trump, you support hate. I cannot be a part of that,” Baez declared in a heartfelt post on her personal site. Bezos, caught off guard, was left speechless by her unwavering conviction. Within hours, Trump fired back on Truth Social, mocking Baez as “another washed-up protest singer chasing relevance.”

But Joan Baez was undeterred. She answered with eight quiet words that silenced Trump — words that carried more power than any insult could:

“Truth doesn’t age, and neither does courage.”

Social media erupted. Artists, fans, and activists rallied behind her, calling it “a masterclass in integrity.” Comment sections filled with tributes, clips of her classic performances, and quotes from her decades-long fight for justice.

For some, it was a flashback to the fearless young woman who once sang for peace on the steps of history. For others, it was a revelation — proof that at eighty-four, Joan Baez’s voice still cuts through noise like a blade of light.

My nephew dnc with my wife at our wedding

David Seidler And Our Ex

David Seidler was married to my ex, Mary Ann Tharaldsen, and thus is in my and Liz Taylor’s family tree. Maybe he can author a Bond movie?

I see a play based upon The Misfits, and Bus Stop, where Tom and Mary Ann Pynchon, end up on the bus to Mexico with Lee Harvey Oswald. What was said, or not said, to detour Oswald from ending Camelot, or, what made up his mind to end the life of JFK, would be the Story of their generation? Belief in dialogue and philosophy was at its peak. If JFK had lived, there would be no Brexit and Trump. The bond between the U.S. Canada and Britain, would be strong. I suspect my ex was recruited by the CIA.

“I did not like it in Mexico…” The writer’s introspection also bothered her. “He wasn’t very present as a lover or a person. I wanted a relationship with someone who wanted to have children, and it became apparent to me that he really didn’t want to do that. He wanted to focus more on his writing.” After some time, the couple moved from Mexico to Texas, where they lived in separate houses. The novelist worked all night and slept all day. “So that isn’t very conducive to a relationship,” Tharaldsen recalled, laughing.“

John Presco 007

| THARALDSEN, MARY ANN married a groom named DAVID SEIDLER in the year 1961 on license number 4200 issued in Brooklyn, New York City, New York, U.S.A. Special thanks to RECLAIM THE RECORDS. Now you may also check Archives for MARY ANN THARALDSEN. |

Mary A Presco

in the California, Divorce Index, 1966-1984

- Add Alternative Information

- Report issue

| Name: | Mary A Presco |

|---|---|

| Spouse Name: | John G |

| Location: | Alameda |

| Date: | 24 Mar 1980 |

http://piaui.folha.uol.com.br/materia/the-fake-hermit/

I did not know Saint Francis began his Mission in Baja California! Did Meher Baba?

Supposedly, Outsider Stacey Pierrot, had an agreement with Carrie Fisher to author the biography of my late sister, Christine Rosamond Presco, the sister-in-law of, Mary Ann Presco, who was married to David Seidler, who won an academy award for his screenplay in the movie ‘The King’s Speech’’. David and Mary Ann will be in the Rosamond Family Tree I am compiling. Rick Partlow will be there because he was married to Christine. Rick won an Emmy for his foley work in the series ‘Battlestar Galactica’. Mary Ann was married to Thomas Pynchon, and he will be in this rosy tree, as will Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor, who was married to Eddy Fisher. Garth Benton did some acting and was married to Allee McBride. Benton did murals in the homes of the Stars.

This is a Starry constellation that I hereby title ‘The Royal Rosamond Space Academy’. As a descendant of the Master of the Falcon Art College in Holland, who commissioned Hieronymus Bosch to execute his otherworldly painting, I am going to teach young people how to get Out There – without drugs! Science Fiction Author, Daemon Knight, wrote a book on Bosch.

Jon

Oakland Tommy

Posted on March 4, 2016 by Royal Rosamond Press

I just found out my ex-wife lived on College Avenue – IN OAKLAND – with Thomas Pynchon. They lived in a big apartment building located next to ‘Ye Olde Hut’ where I did a lot of drinking with my friends, including Paul Drake who Mary Ann encouraged to take up acting. Paul claims he based his tough-guy persona on watching me drink, but I believe he is speaking of Richard Swartz who was a bodyguard for Dederich of Synanon. Richard held the world’s record to the fifty yard dash – on his hands!

Mary Ann did illustrations for a rare book about the Symbionese Liberation Army. Her best friend, Joan (who lived right off college) came home for Thanksgiving and found her whole family blown away by the Black Mau Maus. Her father was a CEO of Standard Oil. Patty Hurst was kidnapped from 2803 Benvenue, which is about ten blocks from the Hut. I thought Mary Ann and I were going to be Facebook friends, then she prohibited any more drama. Maybe I will get an Oscar someday – late in my life – when most of my peers are dead, leaving a thousand writers to guess what became of Pynchon? What about Patty? What us olde ones don’t realize, is, that every seven years you get a new generation, thus withholding information from them – is futile!

“When he finished college, Pynchon was dating a girl named Lilian Laufgraben. Her family was Jewish and preferred that their daughter marry a dentist with the same religion. Heartbroken, the writer turned to some friends for comfort, Mary Ann Tharaldsen and David Seidler, a couple living in Seattle. Tharaldsen worked for Boeing and arranged a job at the company for the young friend. At the time Pynchon was writing his debut novel, V. In the book there’s a Jewish girl, Esther, who gets a nose job. When the surgery was about to start, the character was still awake: “She felt passive, even (a little?) sexually aroused.” Later, “Esther’s eyes were wild; she sobbed quietly, obviously beginning to get second thoughts. ‘Too late now,’ Trench consoled her, grinning. ‘Lay quiet, hey.’” Pynchon takes several pages to describe the mutilation of the girl’s face, without sparing metaphors of sexual penetration. Many of his friends interpret the passage as the novelist’s revenge on Lilian Laufgraben.

As soon as V. was published in 1963, the author quit his job at Boeing and moved to Mexico City, where he believed he would spend less money. He hated Seattle. “It’s a nightmare. If there were no people in it, it would be beautiful,” he wrote in a letter to an old college friend. During a brief trip back to the United States, he started a relationship with Mary Ann Tharaldsen, which led to the end of her marriage.

I called David Seidler, the ex-husband. “Thomas Pynchon? I’d rather not talk about it, thanks,” he said sarcastically. He’s now a theater and film writer and won an Academy Award in 2011 for The King’s Speech. Like George VI, the film’s protagonist, Seidler was born in England and stuttered in his childhood.

Tharaldsen, a technical writer, now 80 and living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, told me a few details about their relationship. “Pynchon didn’t want to really communicate with anybody, except at that time I was the person that he would communicate with.” She agreed to live in Mexico when the two began their relationship. “I did not like it in Mexico…” The writer’s introspection also bothered her. “He wasn’t very present as a lover or a person. I wanted a relationship with someone who wanted to have children, and it became apparent to me that he really didn’t want to do that. He wanted to focus more on his writing.” After some time, the couple moved from Mexico to Texas, where they lived in separate houses. The novelist worked all night and slept all day. “So that isn’t very conducive to a relationship,” Tharaldsen recalled, laughing.

Pynchon’s Catholicism manifested itself mainly in his strict habits. In their five years together, Tharaldsen never saw her boyfriend smoke marijuana (there are reports that he took up weed later on). The author once got annoyed at his girlfriend when she said she wanted to have a drink during the day. “I will not tolerate midday drinking,” he shouted.

Some people guarantee that Tharaldsen served as the inspiration for Oedipa Maas, the protagonist of The Crying of Lot 49. The housewife ditches her husband, disc jockey Wendell “Mucho” Maas, and ventures to California chasing leads on an underground organization. The more she gets caught up in the search, the more she’s egged on by her own paranoia. Countless critics have claimed that Pynchon composes unidimensional and overly ludicrous characters. It’s certainly not the case with Oedipa Maas.

The novelist and Tharaldsen parted ways for good in the late ’60s, when the writer was finishing Gravity’s Rainbow at a house near the ocean in Manhattan Beach, a town near Los Angeles. Retired Army officer Jim Hall, Pynchon’s neighbor at the time, was dating a girl that the writer also knew. “When I met him for the first time, we were drinking wine at his house. Pynchon was very much into thermodynamics and there were stacks of Scientific American magazines in his apartment. My girlfriend said he didn’t want to read anything anybody else had written because he was afraid he’d write it into his work. Since I’d just gotten back from Vietnam, Pynchon asked me several questions about it.” Some of the critics claim that although Gravity’s Rainbow takes place in World War II, the book is about how Americans viewed the Vietnam War. I asked Hall if the novelist had shown paranoid traits at the time. “A little,” he replied. “But considering what we know today about the government’s covert operations at the time, he was right to act that way.”

To divide Tom the man from Pynchon the idea for biographical purposes, however, is to risk the folly in which Lane indulges in Journey into the Mind of [P.], particularly when he speculates that Pynchon was on the bus Lee Harvey Oswald took from Houston, Texas, to Mexico City on September 26, 1963,[23] about a month after Pynchon served as best man at Richard Fariña and Mimi Baez’s wedding on August 21, 1963. Lane never offers an explanation for why Pynchon would travel from California to Texas to return to Mexico rather than take a bus from Pacific Grove, to which he had traveled from Mexico City in August.[24] Lane admits that he is offering nothing more than “ridiculous rumor,” a description he quickly recasts as “ridiculous speculation,” apparently to indicate that the story is his own, but he also conjectures that Pynchon’s “secret,” his reason for avoiding the press, involves the conversation he had with Oswald. “This is the kind of fun people like me can have,” Lane then says. But the speculation isn’t simply ridiculous; it ignores the record, even as it existed at the time of the film’s making. Pynchon had already begun his famed avoidance of the media before Oswald went to Mexico, as George Plimpton, a literary journalist, and Jules Siegel, a former friend, point out in the film just after Lane’s speculation. There is no reasonable way to place Pynchon on a bus with Oswald, despite Lane’s insistence that connections can be forged even if the words we have don’t imply them, or to attribute Pynchon’s desire for privacy to a meeting between him and Kennedy’s assassin. Indeed, it has more recently been revealed that Pynchon headed further north after Fariña’s wedding, meeting up with friends from Cornell, Mary Ann Tharaldsen and David Seidler, in Berkeley, where he remained until “shortly after John F. Kennedy was assassinated.”[25] Pynchon might observe of Lane’s speculation: “Opera librettos, movies and television drama are allowed to get away with all kinds of errors in detail. Too much time in front of the Tube and a writer [or biographical researcher, it turns out] can get to believing the same thing. . . . The lesson here, obvious but now and then overlooked, is just to corroborate one’s data.”[26]

Today is the most momentous day in my life. All my hard work has paid off. Ludwig traveled to Ithaca and hung with Cornell philosophers. My cup runneth over. I am so overjoyed that my grandparents can be put in a group of writers and thinkers – forever! I can remove my sister Christine from the literary hell she was thrown in hours after she died. My relationship with the woman I married, is redeemed. We believed in each other.

John Presco

Wittgenstein’sVisittoIthaca.pdf (cornell.edu)

Pynchon and Philosophy radically reworks our readings of Thomas Pynchon alongside the theoretical perspectives of Wittgenstein, Foucault and Adorno. Rigorous yet readable, Pynchon and Philosophy seeks to recover philosophical readings of Pynchon that work harmoniously, rather than antagonistically, resulting in a wholly fresh approach.

Martin Paul Eve

Chapter in Profils Américains: Thomas Pynchon

Edited by Bénédicte Chorier-Fryd and Gilles Chamerois

Pynchon and Wittgenstein: Ethics, Relativism and Philosophical Methodology

Perhaps the strongest rationale for a philosophico-literary study intersecting Thomas Pynchon

with Ludwig Wittgenstein is that, in the writings of this philosopher, the very nature of philosophy is

reflexively questioned. Within his lifetime Wittgenstein published a single text, Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus, influenced by the logical atomists in which he claimed, initially, to have “solved

all the problems of philosophy” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus x). However, in 1929 he resumed

lecturing and, following his death in 1951, the world was presented with the unfinished product of

these intervening years: the Philosophical Investigations. While many early studies, and indeed this

biographical overview, present a seemingly bi-polar, bi-tonal Wittgenstein, who enacts a retraction of

the Tractatus in the Philosophical Investigations, a closer examination of Wittgenstein’s notebooks and

intermediate remarks reveals that the latter owes its genesis to a critique of the former and was

developed through an accumulation of thought and a gradual transition.

This piece presents a tripartite analysis of the relationship between the philosophical works of

Ludwig Wittgenstein and the novels of Thomas Pynchon. This is broadly structured around three

schools of Wittgenstein scholarship identified by Guy Kahane et al. as the Orthodox Tractatus, the New

Wittgenstein, and several strands of the Orthodox Investigations (Kahane et al. 4-14). Moving from the

earliest affiliation that Pynchon stages between Wittgenstein and Weissman, the underlying theme lies

in Pynchon’s relationship to ethical relativism as it pertains to Nazism. From this it will become clear

that neither relativism of experience and representation, nor an unbounded relativism of non-committal

John Presco Married Mary Ann Tharaldsen

Posted on December 8, 2020 by Royal Rosamond Press

I married Mary Ann Tharaldsen, the ex-wife of Academy Award Winner, David Seidler, who is also in my family tree, along with Rick Partlow who marred my sister, Christine Rosamond Benton, who was married to the muralist, Garth Benton. Partlow won a Grammy. A Cornell paper says Mary Ann was married to Thomas Pynchon and they lived in the Rockridge on College Avenue near where the Hippie Movement began. The Loading Zone played at the Open Theatre. Lead guitarist, Peter Shapiro, played at our wedding reception. A close friend lived nearby and he was asked to contribute to Oliver Stone’s movie. He was a good friend of Jim Morrison and Michael MacLure who taught poetry across the street from the Art College.

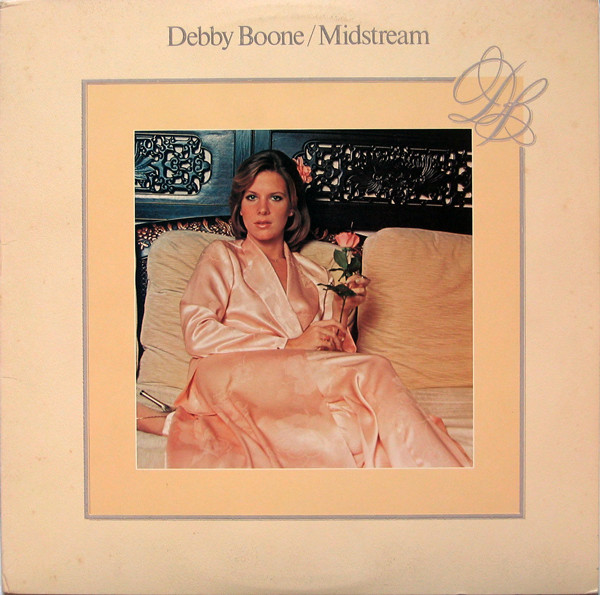

My family were San Francisco Pioneers. Mary Ann’s father came from Norway. My step-daughter, Britt Baumback Murray will be in my family tree. Mary Ann is wearing Marilyn Reed’s ‘Train Dree’ that my sister Christine Rosamond Benton, wore, and Debbie Boone on the cover of her album. Mary Ann discovered the actor, Paul Drake, who played Mick in ‘Sudden Impact’. My friend, Bryan MacLean played at our wedding.

I still admire and love the only woman I married. She found me living and hiding in a little shack working on the fifty drawings of Atlantis. MA lived in Marin. My niece, Shannon Rosamond, read the bad movie script written about her mother. I’m going to use MA’s discovery of me in – our movie about a world famous artist. MA was raving about me, she saying my drawing were worthy of a Master’s Dissertation. She asked me if I was a member of Mensa?

I was blown away when twelve year old Britt showed me her written code after beating the Mother May I machine. I hope our new President will revitalize Gifted Children programs. Britt chose to go to my old school, McCheznie, verses the all white private school in SF. My Stuttmeister-Broderick kin had a house and small farm down the street. Gertrude Stein was a neighbor. I was very proud of my step-daughter for this stellar choice. Our black maid lived nearby and would take Christine home with her on the weekends to stay with the Sisters. At the reception MA danced with my nephew, Cian, when he was about nine. He is ‘The Garden Child’ I did a life-size drawing of MA who did a life-size painting of her good friend, Mimi Farina. I wish I had found time to do a painting of Britt and Mary Ann. Perhaps I will.

After our divorce, I moved downstairs. I remained good friends with MA. One day Britt brought her black girlfriend down to meet me, and show me their cornrow hairdos they just did. I should have become a photographer – along time ago. Her father had her going to the most exclusive private school in SF so she could meet the children of the rich. There had been a legal matter. Looking at these two beauties, was the happy outcome. These beautiful lessons continue to be the highlight of Bay Area History.

It occurs to me why I did not take up photography. I was afraid of becoming a commercial success like my sister, who is depicted as being deluded in saying her gallery ripped her off for millions; when in truth, they only ripped her for $50,000 a year. In this court matter, it never occurred to me me to use Rosamond as a character reference. I just now realize she was the kind of person Mr. Baumbach wanted his daughter to mingle with. The Benton’s were friends of the Getty family. The hut in this painting is more my style. I did this when I was seventeen from memory of the mudflats off the entrance of the Bay Bridge. It is rumored Pynchon lived here. You could only walk to this shack during a special low-tide. How perfect for your average recluse. Note the pier is broken, thus, there is no access to the Recluse, this way. Money can’t buy seclusion like this, because it is……a state of mind. Stoke the potbelly stove. Cue the rain!

John Presco

President: Royal Rosamond Press

Our Home On Miles | Rosamond Press

Christine Rosamond Partlow | Rosamond Press

Black Mask Authors | Rosamond Press

Britt Baumbach Murray | Facebook

Mary A Presco

in the California, Divorce Index, 1966-1984VIEW

| Name: | Mary A Presco |

|---|---|

| Spouse Name: | John G |

| Location: | Alameda |

| Date: | 24 Mar 1980 |

Mary Ann was married to

| Name: | David Seidler |

|---|---|

| Gender: | Male |

| Marriage License Date: | 1961 |

| Marriage License Place: | Brooklyn, New York City, New York, USA |

| Spouse: | Mary Ann Tharaldsen |

| License Number: | 4200 |

Two of Pynchon’s Cornell friends, his future girlfriend Tharaldsen and her then-husband, David Seidler, had moved to Seattle and encouraged Pynchon to join them. Tharaldsen says Pynchon arrived “depressed—very down.” She worked for Boeing, and hooked him up with a job writing technical copy for their in-house guide, Bomarc Service News. The aerospace giant was just then developing the Minuteman, a nuclear-capable missile that likely inspired Pynchon, years later, to cast Germany’s World War II–era V-2 rocket as the screaming menace of Gravity’s Rainbow.

UG. 25, 2013

On the Thomas Pynchon Trail: From the Long Island of His Boyhood to the ‘Yupper West Side’ of His New Novel

By Boris Kachka

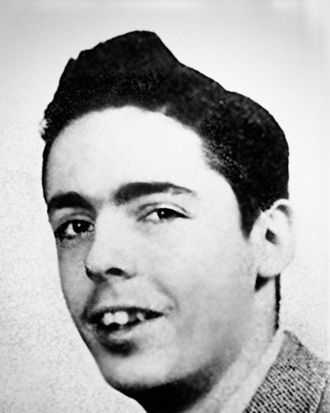

Then: Pynchon, age 16, in his 1953 high-school yearbook, one of the few known photos of the author. Photo: Getty

Let’s get a few things straight. First of all, it’s pronounced “Pynch-ON.” Second, the great and bewildering and, yes, very private novelist is not exactly a recluse. In select company, he’s intensely social and charismatic, and, in spite of those famously shaming Bugs Bunny teeth, he was rarely without a girlfriend for the 30 years he spent wandering and couch-surfing before getting married in 1990. Today, he’s a yuppie—self-confessed, if you read his new novel, Bleeding Edge, as a key to the present life of a man whose travels led one critic to reflect: “Salinger hides; Pynchon runs.” Now Pynchon hides in plain sight, on the Upper West Side, with a family and a history of contradictions: a child of the postwar Establishment determined to reject it; a postmodernist master who’s called himself a “classicist”; a workaholic stoner; a polymath who revels in dirty puns; a literary outsider who’s married to a literary agent; a scourge of capitalism who sent his son to private school and lives in a $1.7 million prewar classic six.

Other high-serious contemporaries, like Don DeLillo and Cormac McCarthy, have avoided most publicity out of a conviction that their work should stand apart, and they’ve largely succeeded; no one stakes them out with telephoto lenses, and everyone takes their reticence as proof of their stature. But Pynchon, by truly going the countercultural distance—running farther, fighting harder, and writing wilder—has crafted a more slippery persona. He doesn’t just challenge his fans; he pranks them, dares them to find out what he’s really about (or maybe just to stop exalting Important Writers in the first place). He’s said he wants to “keep scholars busy for several generations,” but Pynchon academics, deprived of any scrap of history, find themselves turned into stalkers.* The more he flees, the more we want—even now that, at 76, he’s just another local writer you wouldn’t recognize on the street. Though likely you have heard the rumors: He was the Unabomber; he was CIA; he wrote ornery letters to the editor at a small-town newspaper in character as a bag lady. In 1976, a writer named John Calvin Batchelor wrote a long essay arguing that Pynchon didn’t exist and J. D. Salinger had written all the novels. Two decades later, Batchelor and Pynchon published stories on the same page of the newsletter of New York’s Cathedral School, which both their children attended. Their bylines were side by side: “John is a novelist”; “Tom is a writer.”

Tom is quite a writer. He’s been credited, justly, with perfecting encyclopedic postmodernism in his third novel, Gravity’s Rainbow, as well as in other kaleidoscopic epics and a few books he’d call potboilers and others would call the minor work of a giant. Bleeding Edge, out in September, is a love-hate letter to the New York City of a dozen years ago, when Internet 1.0 gave way to the fleeting traumas of September 11. It takes place partly on Long Island—where he was raised—but largely on what his detective heroine knows as “The Yupper West Side.” And it’s a book about something he’s never really addressed before: home.

Batchelor and Pynchon probably know each other by now (though neither has answered interview requests). But their first point of contact was a note Pynchon wrote in response to that original article, postmarked from Malibu and written, curiously, on MGM stationery. “Some of it is true,” Pynchon wrote of the story, “but none of the interesting parts. Keep trying.”

Early on in Gravity’s Rainbow, Tyrone Slothrop muses bitterly on his old-money roots. “Shit, money, and the Word, the three American truths, powering the American mobility, claimed the Slothrops, clasped them for good to the country’s fate. But they did not prosper … about all they did was persist.” It sounds like an ungenerous rendering of the Pynchons, one of those Wasp lineages whose historical prominence leaves their ancestors with a burdened inheritance. For a would-be writer with his own stubborn ideas, it was a source of pride and shame.

The name goes back to Pinco de Normandie, who came to England at the side of William the Conqueror, and carries on through Thomas Ruggles Pynchon, the author’s great-great-uncle, president of Trinity College and the first Pynchon to take issue with the family’s portrayal by another writer (Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote of the “Pyncheons” in The House of the Seven Gables). Thinkers, surveyors, and religious mavericks, the House of Pynchon had settled into middle-class respectability by the time this Thomas Ruggles Pynchon was born near Oyster Bay, Long Island, in 1937.

His father, Thomas Sr., remembered saluting fellow congregant Teddy Roosevelt at church, and remained a staunch Republican along with most of Long Island’s mid-century Establishment. Eisenhower was their man, and the growing white suburbs of postwar New York their constituency. Thomas Sr. went into engineering like his own father but wound up, for a time, in politics. He was Oyster Bay’s superintendent of highways and then, briefly, town supervisor (the equivalent of mayor), until he was accused of complicity in a scheme to overpay a road-surfacing company. At a hearing during his campaign, Pynchon Sr. admitted to taking gifts. “I received some poinsettias and I managed to keep one alive,” he told his accuser, “and it will give me great pleasure to put one on your political grave.” Instead he lost, giving way to the town’s first Democratic supervisor in 32 years. His son was out of the house by then, but he’d seen enough of small-town, big-boss politics to float “The Republican Party Is a Machine” as an alternate title for his first novel, V. A family friend remembers the Pynchons, in their simple frame house, as “a very bookish family” with a large library to complement the ancestral portraits. On Sundays, the three children would split off between churches—Episcopalian for Dad, Catholic for Mom (a nurse from upstate)—and reassemble later at Rothmann’s Steak House.

Tom was lanky and unathletic, with protruding teeth that embarrassed him. He stuttered, too, and felt a kinship with Porky Pig. But that same friend ascribes some of Pynchon’s “social behavior issues” to his “very dysfunctional family”—without elaborating. Pynchon himself almost never talked about his parents, especially in his earlier years. But one afternoon in the mid-sixties, he and his then-girlfriend, Mary Ann Tharaldsen, were driving through Big Sur when she complained of nausea. She wanted to stop at a bar and have a shot to settle her stomach. According to Tharaldsen, he exploded, telling her he would not tolerate midday drinking. When she asked why, he told her he’d seen his mother, after drinking, accidentally puncture his father’s eye with a clothespin. It was the only time, says Tharaldsen, who lived with him, that he ever mentioned his family. “He was disconnected from them,” she says. “There seems to have been something not good there.”

A voracious reader and precocious writer, the young Pynchon skipped two grades, probably before high school, and channeled his suburban alienation into clever parodies of authority. He wrote a series of fictional columns under pseudonyms in his high-school paper in which teachers used drugs, shot off guns, and were driven insane by student pranks. In one story, a leftist agitator “got acquainted with the business end of a night stick the hard way.” Pynchon later recalled that his first “honest-to-God” story was about World War II—though in his recollection it doubled as a plan for how to navigate the stultifying culture of postwar America. “Idealism is no good,” he summarized. “Any concrete dedication to an abstract condition results in unpleasant things like wars.”

Engineering physics, the hardest program at Cornell, was meant to supply Cold War America with its elites—the best and the brightest, junior league. One professor called its students “intellectual supermen”; Pynchon’s old friend David Shetzline remembers them as “the slide-rule boys.” But after less than two years in the major, Pynchon left Cornell in order to enlist in another Cold War operation, the Navy. He once wrote that calculus was “the only class I ever failed,” but he’s always used self-deprecation to deflect inquiries, and professors remembered universally good grades. Tharaldsen says she saw Pynchon’s IQ score, somewhere in the 190s. So why would he leave? He wrote much later about feeling in college “a sense of that other world humming out there”—a sense that would surely nag him from one city to another for the rest of his life. He was also in thrall to Thomas Wolfe and Lord Byron. Most likely he wanted to follow their examples, to experience adventure at ground level and not from the command centers.

Royal Rosamond Space Academy

Posted on September 19, 2016 by Royal Rosamond Press

Here is David, a friend of Mary Ann Tharaldsen and Crew at Cornell, that I put in the Wold Newton family, that should include the works of Thomas Pynchon. The CC went far – but not far enough. With the loss of Richard Farina, there was no going further – enough! We rest on our laurels lining up our regular paydays. I’m glad I got my crew to – retool! Why not write a story about the world Richard and Mimi – would have – tripped in? A young couple invent the New Oz. There is some serious name-dropping going down around David.

Mary Ann drove up from Oakland to see David, and dropped off my dog. I was living near Blue River that burned down in a fire. We drove her father’s Thunderbird cross county.

VRR

On Meeting David Shetzline and Discussing Heckletooth 3 – Nestucca Spit Press Meditations

https://pamplinmedia.com/cr/28-opinion/279580-155069-remembering-oregon-citys-dr-cameron-bangs

On Meeting David Shetzline and Discussing Heckletooth 3

On Sunday, my friend Kevin and I sat down with David Shetzline, author of Heckletooth 3, one the greatest overlooked American novels of the last 50 years, and talked of Heckletooth 3, and other matters, for over three hours. It was easily one of the top moments of my many years reading, studying and writing about Oregon history and literature. It’s right up there with interviewing Dr. Cameron Bangs of Vortex I fame and Maurice Lucas, the bad ass Portland Trail Blazer.

Thank you David, for sharing the remarkable story of this incredible novel, your writing career, and other stories that probably deserve novels or films.

(And thank you to his daughters Andrea and Erika for arranging the meeting.)

Published by Random House in 1969, set in and around the mythical coastal town of Sixes and the Oregon woods, which happened to be engulfed in fire in the plot, Heckletooth 3 is a classic, a forgotten classic, that never saw a paperback edition, was never reprinted, and is almost impossible to find except for a few rare copies. It’s pretty much been purged from Oregon libraries except University of Oregon’s.”

Wold Newton family – Wikipedia

David W. Shetzline (born 1934, Yonkers, New York) is an American author residing in Marcola, Oregon.

Shetzline received his bachelor of arts from Cornell University in 1956 and his masters in literature from the University of Oregon in 1997. His dissertation was entitled “Quantum Dialogues: The Rhetorics of Religion and the Metaphors of Postmodern Science (English, 2000). He served as a paratrooper in the U.S. Army, in addition to being a ditchdigger and a student at Columbia University.[1] He wrote in “the Cornell school” of writing in the 1960s with Thomas Pynchon and Richard Fariña.[2] This school of writing has been defined as having three preoccupations (1) socio-political paranoia, (2) concern with environmental degradation, and (3) awareness of popular culture’s unique impact on the American mind.[3] In addition to Pynchon and Fariña, the Cornell School would also include Mary F. Beal, to whom Shetzline was married. The Cornell School could also be said to include, or be influenced by, Vladimir Nabokov and Kurt Vonnegut. It stands in contrast to Cornell’s older literary traditions, such as the literary traditions represented by E.B. White and Hiram Corson.

In 1968, Shetzline signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[4]

Contents

Primary Fiction[edit]

His first work, DeFord, was published in 1968.[5] DeFord is dedicated to the memory of Fariña.[6] Reviewing DeFord, author Thomas Pynchon wrote, “What makes Shetzline’s voice a truly original and important one is the way he uses these interference-patterns to build his novel, combining an amazing talent for seeing and listening with a yarn-spinner’s native gift for picking you up, keeping you in the spell of the action, the chase, not letting go of you till you’ve said, yes, I see; yes, this is how it is.”[7] DeFord was a seminal contra use of geography as a metaphor.[8]

Heckletooth 3 followed the next year as DeFord, and was noted as a lead text in the new ecology movement of the 1970s.[9] Of Heckletooth 3, The Whole Earth Catalog wrote, “[t]here are some writers and books that I only hear about from others. William Eastlake is one. So is David Shetzline, notably for his forest fire novel Heckletooth 3. Ken Kesey went on about it to me years ago. And last week Don Carpenter firmly put the book into my hand. Well they’ve got my agreement. My summer logging the Oregon woods tells me that Shetzline has the work right, the fire and the men right. He especially has the language – Oregon laconic. It’s an introspective action-novel about virtue. I mean, about detail.”[10]

Other works[edit]

A short story, “A Country of Painted Freaks” appeared in the Paris Review in 1972.[11] Shetzline also conducted the critically acclaimed memoir interviews of William Appleman Williams in 1976, entitled Typescript: A Boy from Iowa Becomes a Revolutionary.[12]

Network[edit]

Shetzline was friends with both Fariña and Pynchon.[13] As Shetzline noted regarding the relationship between Fariña and Pynchon, “I think Tom recognized that Richard had a magic with language, that he was genuinely gifted, and I think Tom recognized that Richard worked with his gifts, he worked consciously to hone them. Tom always hung back. You didn’t find out much about his writing from him, but he was always complaining that he wasn’t getting enough writing done, and that is the tip-off that somebody is absolutely haunted as a writer. Richard knew Tom was as serious about writing as he was. I think Pynchon was also fascinated with Richard’s effect on women, which was powerful. Pynchon developed a capacity to appeal to women who would then sort of go after him.”[14] In the foreword to Greening the Lyre, David Gilcrest described Shetzline as “a true artisan of the pen and fly rod, has earned my respect and thanks as an exemplar in all things philosophical and anadromous.”[15]

He is currently an organizer of the Wickes Beal Studio, in Oregon.

Sharon Family Reunion at Palace Hotel | Rosamond Press

No More Waiting For Van Gogh | Rosamond Press

Get Out Of Montana | Rosamond Press

Mimi Farina In Concord | Rosamond Press

Fearless Girl of the Graffitti Art Labyrinth | Rosamond Press

Blows Against the Empire – Wikipedia

We Took Over The World | Rosamond Press

Blows Against the Empire is a concept album by Paul Kantner, released under the name Paul Kantner and Jefferson Starship. It is the first album to use the “Starship” moniker, a name which Kantner and Grace Slick would later use for the band Jefferson Starship that emerged after Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen left Jefferson Airplane. From a commercial standpoint, it performed comparably to Jefferson Airplane albums of the era, peaking at No. 20 on the Billboard 200 and receiving a RIAA gold certification.[1] It was one of the first two albums to be nominated for a Hugo Award in the category of Best Dramatic Presentation.[2]

Mimi Farina In Concord

Posted on December 9, 2020 by Royal Rosamond Press

I awoke from my Old Man Nap and exclaimed;

“This is my life? Holy shit! I took on Scientology – and lost?”

According to Leah Remini the disappearance of your child by Scientologist is designed to shut your ass up – but good! It surely throws you off balance – and puts you on the defensive. They knew I had a blog. If I wrote anything NEGATIVE about them, then I may never see my MINOR CHILD….again!

Scientology Wants Celebrities | Rosamond Press

For some reason, Tim O’Connor popped into my mind. I am still trying to figure out why he didn’t want me to put any of his poems on my blog. His famous father died two years ago, and I wondered if he was writing a biography – and my famous sister would be in it. Christine and Tim were lovers for a short while. Was this more grabbing from THE PILE full of narcissistic nutrients? Infant Melba has been – hauled off by a total stranger. This could be a case of stalking because when she finally made contact she started ragging on Rena Easton – my muse!

What the fuck!

“What’s your mother’s name? I want to see if she is related to Royal Rosamond.

“I’m not going to tell you!”

WTF!

Anyway…Tim is the reason I was detained by a LA Cop in a Hawaii shirt and cut-offs as I came down the escalator in the Greyhound bus depot. I was put in this little room and accused of being a professional demonstrator on my way to Oakland to be with Phony Joanie at her protests at the Oakland Induction Center. Joan and her sister, Mimi, were arrested and put in Santa Rita. My cop took out a truncheon and was going to work me over – while I was in handcuffs. He was stopped. I was taken to jail where after two days I am taken to a detective room and shown pics of Tim O’Connor;

“Do you know this guy?”

“No!”

“How did he get your driver’s liscence.”

“I dont know!”

“You’re lying!”

This was true. I had gone to visit my family and Tim was living with Vicki and Rosemary. His father threw him out – again. He wanted to go see a band on the Strip and borrowed my license to get in. He did not tell me the next morning he got arrested for Marijuana procession. The LA cops are trying to pin that bust on me. I told them to do a match of the fingerprints – which I believe they already did. They wanted A NAME for The Phantom of the Strip. This is the dude that doses Mafia Max. He went to the same school as my sister and knew all the actor’s children. Did he know River Phoenix? I never confronted our family friend who looks like Doc in Inherent Vice. and lived in Venice and played on the boardwalk. Tim played at my wedding reception. How did Mary Ann get involved in all these Hollywood types.

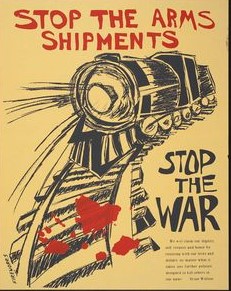

Actor Tim O’Connor Leaves The Planet | Rosamond Press

Two days ago I discovered my facebook friend lived in Concord around the time the Prescos did. He tells me he had a 50 Caliber machine gun pointed at him when he and a friend sent rockets soaring into the air. He said he had just read the story Mutiny about the black navy men that were tried for treason after the huge explosion at Port Chicago. Mimi was in Concord protesting, and tying to stop munitions trains from eventually delivering white phosphorous to Vietnam. Mimi lived in Marin where I founded MARIN SHIPMATES that I want to see funded by the Buck Foundation as part of BLM. Two days ago I posted on General Loyd Austin being made head of our armed forces. Is he going to be a Uncle Tom for Uncle Buck – who is also the money Uncle Sam gives the military every year and is being held by Big King Buck. WTF!

Mutiny (1999 film) – Wikipedia

Write your new VP, Kamala Harris, who was a District Attorney for Oakland and San Francisco, and bid her to look into these matters where the military took on U.S. Citizens who were legally protesting. One man got run over by a train in……CONCORD…..by

UNCLE SAM BUCK

John Presco

The Marin Shipmates | Rosamond Press

Black Panther Party Gallery and Museum | Rosamond Press

Bread and Roses of Marin

Posted on August 21, 2017by Royal Rosamond Press

Did Beryl Buck ever meet, or see, Mimi Farina, who was a good friend of my ex? Where are Beryl’s things and letters? Did she ever buy a ticket to go see Bread&Roses?

Above is a pic of where B&R was located in Mill Valley in Marin Couty. Mimi lived on Mount Tamalpais. Mimi created the ideal charity. She is the model for all Buck Foundations. Instead we get a dude playing with his expensive toys.

Sydney Morris screwed up the Brett Weston creative legacy. I had my mother call him and he and Stacey were about to throw away our family photos.

“Do you want them?”

“Of course I want them!”

These are fucking lawyers! They should be banned from getting near creative people.

Jon

Mimi died on July 18, 2001, at her home on Mt. Tamalpais in Mill Valley, California, surrounded by her family and close friends. Her vision lives on in the form of Bread & Roses today.

The Mission Statement for this inspirational program is as follows:

Bread & Roses is dedicated to uplifting the human spirit by providing free, live, quality entertainment to people who live in institutions or are otherwise isolated from society. Our performances: enrich the soul and promote wellness through the healing power of the performing arts; create a sense of community for our professional performers, in a non-commercial setting in which they can donate their talents to inspire and be inspired; provide an opportunity for non-performing volunteers to contribute a variety of skills and resources that support our humanitarian services and increase the impact of donor contributions. In carrying out this mission, Bread & Roses seeks to create a social awareness of people who are isolated from society, and to encourage the development of similar organizations in other communities.

Pynchon’s Eclipse House

Posted on August 21, 2017by Royal Rosamond Press

Here is the apartment my ex lived in with Thomas Pynchon. It has “ECLIPSE” written all over it!

Don’t you think he is keen on the Buck Hangars and this Nazi talk? Mary Ann Tharaldsen was Christine Rosamond’s sister-in-law. She got Tom a job at Boeing. I bet your Bob Buck makes Pynchon – even more paranoiac! There’s “DOOMSDAY” written all over Bob.

Jon Presco

“Engineering physics, the hardest program at Cornell, was meant to supply Cold War America with its elites—the best and the brightest, junior league. One professor called its students “intellectual supermen”; Pynchon’s old friend David Shetzline remembers them as “the slide-rule boys.” But after less than two years in the major, Pynchon left Cornell in order to enlist in another Cold War operation, the Navy. He once wrote that calculus was “the only class I ever failed,” but he’s always used self-deprecation to deflect inquiries, and professors remembered universally good grades. Tharaldsen says she saw Pynchon’s IQ score, somewhere in the 190s. So why would he leave? He wrote much later about feeling in college “a sense of that other world humming out there”—a sense that would surely nag him from one city to another for the rest of his life. He was also in thrall to Thomas Wolfe and Lord Byron. Most likely he wanted to follow their examples, to experience adventure at ground level and not from the command centers.

What finally smoked him out was Richard Fariña’s wedding to Mimi Baez, sister of the famous folk singer. In August, Pynchon took a bus up the California coast to serve as his friend’s best man. Remembering the visit soon after, Fariña portrayed Pynchon with his head buried in Scientific American before eventually “coming to life with the tacos.” Pynchon later wrote to Mimi that Fariña teased him about his “anti-photograph Thing … what’s the matter, you afraid people are going to stick pins; pour aqua regia? So how could I tell him yeah, yeah right, you got it.”

After Fariña’s wedding, Pynchon went up to Berkeley, where he met up with Tharaldsen and Seidler. For years, Pynchon trackers have wondered about Tharaldsen, listed as married to Pynchon in a 1966–67 alumni directory. The real story is not of a secret marriage but a distressing divorce—hers from Seidler. Pynchon and Tharaldsen quickly fell in love, and when Pynchon went back to Mexico City shortly after John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Tharaldsen soon followed.

In Mexico, Tharaldsen says, Pynchon wrote all night, slept all day, and kept mostly to himself. When he didn’t write, he read—mainly Latin American writers like Jorge Luis Borges, a big influence on his second novel, The Crying of Lot 49. (He also translated Julio Cortázar’s short story “Axolotl.”) His odd writing habits persisted throughout his life; later, when he was in the throes of a chapter, he’d live off junk food (and sometimes pot). He’d cover the windows with black sheets, never answer the door, and avoid anything that smelled of obligation. He often worked on multiple books at once—three or four in the mid-sixties—and a friend remembers him bringing up the subject of 1997’s Mason & Dixon in 1970.

Tharaldsen grew bored of the routine. Soon they moved to Houston, then to Manhattan Beach. Tharaldsen, a painter, did a portrait of Pynchon with a pig on his shoulder, referencing a pig figurine he’d always carry in his pocket, talking to it on the street or at the movies. (He still identified closely with the animals, collecting swine paraphernalia and even signing a note to friends with a drawing of a pig.) Once Tharaldsen painted a man with massive teeth devouring a burger, which she titled Bottomless, Unfillable Nothingness. Pynchon thought it was him, and hated it. Tharaldsen insists it wasn’t, but their friend Mary Beal isn’t so sure. “I know she regarded him as devouring people. I think in the sense that he—well, I shouldn’t say this, because all writers do it. Writers use people.”

Tharaldsen hated L.A., and decided to go back to school in Berkeley. “I thought they were unserious sort of beach people—lazy bums! But Tom didn’t care because he was inside all day and writing all night.” At the moment, eager to break with his publisher, Lippincott (and rejoin Cork Smith, since departed to Viking), he saw Lot 49 as a quickie “potboiler” meant to break his option with the house—forcing them to either reject it, liberating him, or pay him $10,000. They paid him, defying his own low opinion of it. In his introduction to Slow Learner, a later collection of his early stories, he’d write that with Lot 49, “I seem to have forgotten most of what I thought I’d learned up till then.” Now it’s required reading in college courses, a gateway drug to the serious stuff. Which, of course, was his next book: Gravity’s Rainbow.

War protests[edit]

In 1982, at the height of U.S. intervention in the Central American Crisis, Concord Naval Weapons Station was the site of daily anti-war protests against the shipment of weapons to Central America, including white phosphorus. On September 1, 1987 U.S. Air Force veteran and peace activist Brian Willson was run over by a Navy munitions train while attempting to stop the train by sitting on the railroad tracks outside the compound gates. He suffered a fractured skull and the amputation of both his legs below the knee, among other injuries. The incident that caused Mr. Willson’s injury were never prosecuted in criminal court, but a civil suit was filed and an out-of-court settlement was awarded.

In the days afterward, thousands participated by protesting the actions of the train’s crew and the munitions shipment including Jesse Jackson and Joan Baez. During the demonstration, anti-war protesters dismantled several hundred feet of Navy railroad tracks located outside of the base, while police and U.S. Marines looked on. Billy Nessen, a prominent Berkeley-based activist, was subsequently charged with organizing the track removal, and his trial resulted in a plea bargain that involved no jail time.

Share this:Share this:

Hippie House

What we may be looking at in this article, is the first shot fired in the sexual revolution – and the Free Speech Movement! Why not…

THE LIBERAL HIPPIE MOVEMENT…..

that the President and FBI Director Kash Patal are putting in,,,

THE CROSSHAIRS OF SHAME

Dean Mallott spoke out against McCarthyism, but founded a modern day Inquisition/ My alleged ancestor was forced to take part in the Spanish Inquisition, and found three Protestants guilty. They were strangled to death. Below is a video of Patal being grilled by a Senator.

“In the Fifties, Cornell was slow to sense the new mood of postwar students with respect to sexuality, which was shaped, in part, by the returning World War II veterans, who felt themselves quite capable of regulating their own personal and social conduct. This would lead to a dramatic confrontation between students and President Deane Malott in 1958 over the University’s claim in loco parentis to regulate student social and sexual actions and even at titudes.

In 1951, Malott accepted the position of 6th president of Cornell University. His 12-year term as president brought about the era of ‘Big Science‘ at Cornell: in 1961 sponsored research funding came to over $39 million. His term also saw the construction of new campuses for the School of Labor Relations and the Colleges of Engineering and Veterinary Medicine as well as other major facilities, including the Arecibo Observatory and Lynah Rink. Though a social conservative, Malott was publicly very critical of McCarthyism; he saw it as a major threat to academic freedom.

After his retirement from Cornell, he would go on to serve on the boards of B.F. Goodrich, Owens-Corning, and General Mills.

- The martyrs were three Augustinian monks from the Augustinian friary in Antwerp, captured after the friary was destroyed by Protestant reformers.

- The three monks were given the choice to recant their Catholic faith or face execution.

- Two of the monks, Hendrik Voes and Jan van Woerden (the search result uses “Johann Esschen”), were executed by being strangled and then burned at the stake in Brussels in 1523.

- The third monk, Lambert Thorn, was not executed until 1528.

Hippie House

Campus Confrontation, 1958

Cornell University Press recently published Cornell: A History, 1940–2015, which picks up where A History of Cornell (by Morris Bishop 1913, PhD ’26) left off. In an excerpt, its authors describe a seminal event that marked the beginning of the end of in loco parentis and foreshadowed much campus turmoil to come.

By Glenn Altschuler & Isaac Kramnick

Calm before the storm: The campus in the mid-Fifties, when conformity reigned.

Photo: 1955 Cornellian

As Cornell launches its sesquicentennial celebration, it’s time for an update. A History of Cornell, the much-admired account by Morris Bishop 1913, PhD ’26, ends in 1951, with the naming of Deane Malott as the University’s sixth president. A great deal has happened since then. So, eleven years ago, the task of bringing Cornell’s history up to the present was tackled by Glenn Altschuler and Isaac Kramnick, two of the University’s longest-serving and best-known professors. Altschuler, PhD ’76, is the Litwin Professor of American Studies and dean of the School of Continuing Education and Summer Sessions. He also served as vice president for university relations. Kramnick is the Schwartz Professor of Government and was vice provost for undergraduate education from 2001 to 2005. They were given access to presidential papers in the University Archive and drew from a wide variety of other sources— including this magazine. Their book, Cornell: A History, 1940–2015, has just been published by Cornell University Press. In this exclusive excerpt, the authors recount the tale of the “apartment riot” of 1958, a seminal event that foreshadowed much campus turmoil to come.

In the Fifties, Cornell was slow to sense the new mood of postwar students with respect to sexuality, which was shaped, in part, by the returning World War II veterans, who felt themselves quite capable of regulating their own personal and social conduct. This would lead to a dramatic confrontation between students and President Deane Malott in 1958 over the University’s claim in loco parentis to regulate student social and sexual actions and even at titudes.

Fighting words: Ronald Sukenick ’55 (back row, far left, with the editorial board of the Cornell Writer) penned a short story that outraged President Deane Malott (below left).

Photo: 1955 Cornellian

There was a foreshadowing of this cultural lag in late 1953, when Malott took offense at the presence of what he la beled “filthy words” in a short story published in the student literary journal, the Cornell Writer. The president complained in a letter to Baxter Hathaway, the English professor who was the faculty adviser to the publication, that because “Cornell” appeared on the masthead, “a public relations problem” loomed. He urged Hathaway to re move obscenities from future published student pieces. The president’s anger reveals much about him and the en suing confrontation between him and the students. The story, “Indian Love Call,” by Ronald Sukenick ’55 (who became an English professor at the University of Colorado and author of five novels), contained, in fact, no obscene phrases, no four- letter Anglo-Saxon words, no anatomical or even erotically charged passages. The filth Malott objects to is clearly the general “immorality” in the story’s portrait of college life, which is a narrative about drunken, dissolute college students—disaffected intellectuals whose friendships include casual sex, never described.

Deane Malott.

Photo: 1956 Cornellian

Hathaway responded to Malott’s letter with the claim that “I have no business to act as censor.” Not all students write as their predecessors in the “Genteel Tradition” did, he added in a mini-lecture, describing the new “realist school” in contemporary fiction, concerned with “real-life behavior.” Hathaway concluded by noting that “there is a point somewhere within which the educational pro-cess must be protected against the demands of good public re lations.” An infuriated Malott replied, “I cannot believe there is literary or educational value in filthy words. I sup pose as an administrator it is scarcely appropriate for me to have opinions on education, but certainly to publish filth seems even to a layman scarcely a part of the educational process, regardless of how educational may be either the reading or the writing of it.”

Malott immediately referred the matter to the Faculty Committee on Student Activities and Student Conduct, which that spring had done his bidding by reprimanding editors of the Cornell Daily Sun and the Widow for “obscene and profane material appearing within their pages.” The president urged a similar rebuke to the editor of the Cornell Writer and the author of the offensive story. With the Daily Sun editorializing against “the forces of right eousness, virtue, and purity on the Cornell campus” and English professors opposing what they labeled the “clear- cut trend to bring open expression of student thought under tight control,” the Faculty Committee declined to act on the president’s request that the two students be reprimanded. The story was “a bona fide effort in the field of modern realistic writing,” the committee held, even if, as committee members acknowledged, it “went beyond the limits of the standards of good taste.” Around campus, jokes were told of faculty responding to an angry Malott asking if there was nothing professors found unacceptable, with “Yes, Mr. President, plagiarism.”

The faculty would soon have its authority in such matters undermined. When the same Faculty Committee in late 1953 allowed male students to entertain women “guests” in unchaperoned apartments with two or more rooms, if at least two non-freshman women students were present, and permitted the women to remain in the apartment until midnight, or 1 a.m. on Sunday, the president had had enough. Ignoring a poll that revealed that half of women students thought they should be allowed to visit men’s apartments “under any circumstances,” he decided in May 1955 to move responsibility for supervising and disciplining student conduct and extracurricular activities from the faculty, where it had resided since 1901, to the president. Despite almost unanimous faculty disapproval and the resignation of the dean of the faculty, William Farnham 1918, LLB ’22, the Board of Trustees changed the University’s bylaws so that the formerly autonomous Faculty Committee would henceforth be appointed by and re port to the president. Whereas usually seventy-five to one hundred professors showed up at faculty meetings, 300 came to the one responding to the Mal ott-inspired board action. A resolution condemning the bylaws change as “contrary to sound educational policy” was passed by acclamation. So began the multiyear Malott “morals crusade.”

Skirmishes saw Malott’s own dean of women, Dorothy Brooks, recommend in the spring of 1957 that, except for a ban on freshman women, all regulations on apartment parties be abolished. Brooks pointed out that 62 percent of parents gave “blanket permission” for their sophomore daughters to attend parties. Malott would not budge, writ ing to the chair of the Faculty Committee—a committee that now reported to him—that allowing male students an unrestricted right to entertain female students in their apartments at night would be “in complete disregard of con ventional mores and morals.”

The conflict escalated after a particularly alcohol-sodden Spring Weekend, which saw a student, Frederick Nowicki ’60, die in the University infirmary from a fractured skull suffered in a fifteen-foot fall from a second-floor porch at Phi Kappa Tau fraternity house at 5:30 a.m. on Saturday, May 11, 1957. On Sunday, Malott called a group of student leaders to his office. He demanded that they take action to prevent any recurrence of “rowdiness, vandalism, and public displays of drunkenness.” Agreeing that “wild and drunkard parties” had to be prevented, the students promised to establish new social standards for parties. In the fall, they proposed earlier closing hours, along with limitations on “party-hopping” and “public” drinking. The President’s Committee on Student Activities, which had recently imposed an unpopular alcohol ban in Schoellkopf Stadium, found the student-authored social code inadequate, especially in controlling sexual activity, and in December announced much more stringent rules. The committee specified, for example, that for four hours, from 3 to 7 a.m. Saturday and 4 to 8 a.m. Sunday, at overnight parties, there could be no one of the opposite sex present in any room or house on or off campus.

In January 1958, the Student Council by a vote of 16–0 rejected the Faculty Committee’s “university social standards,” as did the Interfraternity Council and the Women’s Self-Government Association. Malott replied by informing an open meeting of 350 students, faculty, and administrators in the Memorial Room of Willard Straight Hall, with another 175 students listening to a broadcast of the session in nearby rooms, that neither students nor faculty had jurisdiction over matters in the social code; the Board of Trustees gave authority to him alone over such issues. When asked about the appropriate role of the University in setting up a “standard morality” for students, Malott shot back that “students should conform to the mores of the society in which we live. Most students have acceptable habits of conduct. Some do not, and have to be controlled.”

A tense truce persisted through most of the remaining spring term. Invoking historian Carl Becker’s already canonical words, Malott repeatedly insisted on the need for student responsibility to temper their excessive freedom. The Daily Sun in its editorials, letters, and columns responded that “the imposition and codification of responsibility is a dangerous precedent to set. It is not a question of Freedom with Responsibility, but of the insult given to the students by the imposition of rules, which if followed make the student moral and responsible, which if broken make the student immoral and irresponsible.” The chair of the president’s Faculty Committee, Theresa Humphreyville, who taught in Home Economics, defended the code in terms of the University’s role “as a parent, providing a place to live, and an atmosphere to meet and get together, both normally the functions of a family, a role which parents put the University in. The University feels responsible for what happens to students while they are here.” She told a Student Council meeting that “there was just too much social activity at the University. Anything which limits partying provides an opportunity to pursue academics.” In response, Cornell erupted in the first broadly based “student power” protest of the kind that swept American campuses during the Sixties.

Open warfare broke out in mid-May, when Humphreyville and Lloyd Elliott, the executive assistant to Malott, informed the Student Council that the president’s Faculty Committee was seriously considering restoring the ban on unchaperoned parties in off-campus apartments. Apartment entertaining, Elliott told the council, “was not in the best interests of an educational environment leading to co-educational achievements.” The University “should lead in the ethics and moral development of students.” Humphreyville added that “since the apartment situation is conducive to petting and intercourse it is an area with which the University should be properly concerned.”

Daily Sun editor Kirkpatrick Sale ’58.

Photo: Daily Sun

Students countered first with a flurry of letters and opinion pieces in the Daily Sun. “No amount of legislation is ever going to prevent society—much less students—from ‘necking,’” an editorial proclaimed. “The administration is operating under the magnificently false assumption that our parents do not trust us unchaperoned in a room with the opposite sex,” wrote Stephanie Green ’59. “The main rationale for the Committee’s contemplated action is a Victorian belief in the fundamental immorality of sex; the administration plans to change bad old Cornell into a Bible Sect Seminary,” claimed another student, “name withheld.” “It is time for the University to abandon its ill-conceived and non-purposeful attempt to impose moral ‘standards’ on its student body,” declared Stephen A. Schuker ’59. And Jay Cunningham ’58 asserted that “what really hurts is seeing the University set itself up as a molly-coddling goddess, a sort of Johnny-come-lately Mom in the form of a new and all powerful pseudo-parent.”

Midnight mayhem: Protesters at the raucous Sage Hall rally (right) included Daily Sun editor Kirkpatrick Sale ’58.

Photo: Daily Sun

On Friday and Saturday, May 23 and 24, the students took to the streets in anti-Malott rioting, in an unprecedented protest against their own administration. The leaders were John Kirkpatrick Sale ’58 and Richard Fariña ’59, who shared an apartment at 109 College Avenue. Sale, the son of Cornell English professor William Sale, had grown up in Ithaca and in 1958 was editor of the Daily Sun. He was a student radical, who a year and a half earlier had written a Sun opinion piece that decried student apathy and acceptance of the Fifties status quo. “Cannot Cornell take its place with other people across the country in refuting the abominable notion of The Silent Generation?” he asked. Sale’s editorials relentlessly criticized Malott for treating students as if they were children and encouraged students to take direct action. On May 13, he had written, “Let Cornell students not sit passively by once more while the President’s Committee takes away privileges and attempts to define morality for the undergraduate. If there is resistance to the elimination of apartment parties, let it be formulated now.”

We know from Fariña’s critically acclaimed 1966 novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, that “resistance” was in fact being planned. Fariña, whose first writings appeared in the tainted Cornell Writer, and who would also become a respected folk singer and composer (and husband of Mimi Baez), would die in a motorcycle accident two days after his novel’s publication. The novel describes endless drug- and drink-filled planning sessions in the spring of 1958 with campus anarchists and the editor of the Daily Sun. They designed protests against “Sylvia Pankhurst” (Fariña’s fictional Cornell vice president, a composite of Humphreyville and Elliott), who, the novel relates, “actually said that male apartments, if you follow me, are conducive to petting and intercourse.”

Richard Fariña ’59

Photo: THEMUSICSOVER.COM

One thousand students gathered in front of Willard Straight Hall at ten o’clock on Friday morning, unsure of what was going to happen until Sale stood up and addressed the group: “We’re here to protest the social code, and the crushing of the faculty. Today is a day for action. We don’t need people who are going to chicken out.” The group then marched to Day Hall, chanting such slogans as “We want Malott shot” and “No ban.” Malott, “tall, tanned, graying, and tending toward natty blue suits and red neckties,” according to Newsweek’s account, had already “made a fortunate escape.” Eventually the crowd circled the Arts Quad and returned to Day Hall. Sale announced that the women at Sage Hall would stay out late that night to protest the proposed ban and the existing curfew rules. The group then sang the Alma Mater, but before breaking up at 10:50 to go to classes, a few students threw eggs at Day Hall, some of which splattered the dean of men, Frank Baldwin ’22, who had been speaking to them from the steps of the building, and whose daughter Polly [Mary Baldwin Gott ’58, BFA ’59] was one of the protesters. Despite this incident, a faculty observer deemed the protest “orderly and good-natured,” commending the organizers for stationing students in front of the doors of Boardman and Goldwin Smith to prevent anyone from interfering with classes.

That night, more than 3,000 students gathered in front of Sage to urge women students to stay out after the 12:30 a.m. curfew. Some of them carried flares and torches, and from time to time firecrackers were set off. Officers of the Student Council and the Women’s Self-Government Association tried to calm the crowd. P. K. Kellogg ’59, president of the council, said he had met with University officials that afternoon and saw some evidence that administrators might not impose the ban.

‘We’re here to protest the social code, and the crushing of the faculty,’ Sale said. ‘Today is a day for action. We don’t need people who are going to chicken out.’They were shouted down as “puppets” with cries of “We want Sale.” And they got him. Proclaiming “what we need now is less Student Council and more student body,” Sale asked the group if they wanted the new tighter rules governing house and apartment parties, and a chant went up: “We want a new president.” When more than 100 women did not return to their dorms after 12:30, the protest turned nastier, with a burning effigy of Malott hanged from an elm tree in front of Sage. Sale and others took down the effigy, put out the flames, and tried to convince the crowd that, having accomplished its purpose of encouraging women students to break their curfew, it should disperse. When a few students cried out that the protesters should march to the president’s home in Cayuga Heights, Sale tried—and failed—to dissuade them.

Deane Malott was the first president of Cornell not to live in Andrew Dickson White’s house on central campus. He resided about half a mile away, on Oak Hill Road in a University-purchased home. On this particular weekend, he and his wife, Eleanor, had as houseguests John Collyer 1917, chairman of the Board of Trustees, and his wife. On Friday afternoon the Coll-yers had presented the University the new Collyer Boathouse. On Saturday morning at about one o’clock, a leaderless throng of almost 1,000 students arrived at Malott’s house, trampling the lawn and landscaping, setting off a smoke bomb, and throwing eggs and stones, all the while chanting “Go back to Kansas.” Appearing on his front steps, Malott told them, “This University will never be swayed by mob rule.” Obscenities were shouted at him, and some windows were smashed. On seeing the demonstrators, Mrs. Collyer reportedly said to her husband, “Are these the boys you are giving the boathouse to, John?” The next morning, Sale, who had not gone to Cayuga Heights, said that he “regretted the violence against President Malott, and expressed the hope that there would be no further violence on campus.”

Fiery tempers: Sage protesters burned Malott in effigy.

Photo: Daily Sun

It was too late for regrets. Sale, Fariña, and two other students were suspended by the dean of men on Sunday night for “inciting fellow students to riot.” They were not permitted to attend classes or otherwise appear on campus until the Men’s Judiciary Board considered the charges against them. Sale repeated his criticism of the violence at Oak Hill Road, but condemned the president and “the entire attitude of the Cornell administration over the last eight years to limit the student voice, to limit faculty powers, and to impose standards of morality and social behavior on the students.”

As the Men’s Judiciary Board, composed of eight undergraduates appointed by the Student Council, considered its verdict, there was a flurry of activity on campus. A petition supporting the four students was signed by 1,860 Cornellians, and a sit-down strike at Day Hall to end the “reign of error” was called off at the urging of friends of the suspended students. Lloyd Elliott, an architect of the social code, resigned, to become president of the University of Maine. He was replaced by John Summerskill, one of the directors of the new Gannett Health Clinic, associate professor of clinical and preventive medicine, and an authority on student psychology. With a new title, vice president for student affairs, Summerskill quickly orchestrated a meeting of the four suspended students with Malott to apologize for the violence. A bit chastened, perhaps, the president asked Summerskill to create an advisory committee of students “to assure a constant and free flow of opinion and understanding between the administration and the students.” Speaking on WVBR, Theresa Humphreyville backed away from a ban on unchaperoned parties, claiming to favor “spot checks” to assess “their effect on the general social atmosphere at Cornell.” Off campus, the protest was front-page news in the national press, with the New York Journal-American story displaying the headline Four SUSPENDED BY CORNELL AFTER 2-DAY RIOT OVER GIRLS. The San Francisco Chronicle‘s story was headed STUDENTS STNE HEAD OF CORNELL.

In a meeting that began at 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday and lasted until 6:30 a.m. Wednesday, the Men’s Judiciary Board decided to put Sale and Fariña on “parole” and to give reprimands to the other two miscreants. The board rejected suspension, it reported, because none of the four “had participated in the acts of violence which marred the demonstrations.” Because “they had in large part contributed to the atmosphere out of which the violence arose,” Fariña and Sale were required by the parole to be under the direct supervision of a faculty member or University administrator to whom they had to report periodically.

Sale had the last word in a full-page editorial in the Daily Sun a month later on graduation day. Anticipating the general mood of Sixties student radicalism, he offered a blistering attack on “the lack of a sound intellectual atmosphere at this campus,” where there is no longer any chance “for a student talking and thinking with his professors.” He was convinced that “as long as the fraternity social atmosphere at Cornell is dominant, the intellectual life of the students is irreparably damaged.” The Malott administration, Sale added, “seems to have had very little regard for the magnificent tradition of Cornell.” Day Hall was “far too impressed with efficiency . . . too [much] big business and not enough Cornell,” and all too willing to trample on “student rights and student freedom.” Sale would become a founding member of the national Students for a Democratic Society, the history of which he would write in his long career as a public intellectual and author of books on Columbus, Robert Fulton, and the Luddites.

During the Board of Trustees meeting on that very weekend, Collyer presented a telegram from Humphreyville suggesting that the board should annul the parole of Sale and Fariña, suspend them, and thereby prevent Sale, a senior, from graduating. The trustees declined, voting 18–7 to uphold the decision of the Men’s Judiciary Board. The trustees also voted, however, “that John Kirkpatrick Sale be not admitted for further study in any division of the University without approval of this committee.” Meanwhile, graduating Hotel school students gave Malott a two-layer marble cake with the note, “Whenever you receive eggs from students in the future, they will be in this form.”

Malott remained ambivalent in the wake of the riots. Sobered by the intensity of student anger, he seemed content to turn over student issues to Summerskill and the newly created Student Advisory Committee. He would accept dramatic policy innovations brought by Summerskill that fall. But a part of him resented the catastrophic ending of his morals war. “My attempts to bring the University within a framework of decent standards is primarily the cause of their rebellion,” he insisted. Three days later, however, he wrote to the president of Ohio University that the mob was “not vicious or malicious” but simply “trying to make a point—which I don’t think was valid, to be sure, that they were getting too many rules and regulations inhibiting their social activities.”

Malott was particularly hurt by a trustee revolt over the affair, led by Arthur Dean 1919, JD ’23, and Maxwell Upson 1899. In the midst of the May crisis, Dean had urged privately “that the President has to be relieved of his central, untenable position in the handling of these social disciplinary cases.” Upson went even further, becoming the ringleader of a veritable coup, unsuccessful to be sure, but the nature of which he ultimately shared with the president in an unusually candid letter. He had, he wrote, been “under great pressure from many of my co-trustees, the alumni and professors” to do something about “the marked and severe criticism of some of your methods, during the past three or four years.” Upson assured Malott that he had defended him in the past, “always hoping and expecting a betterment of the situation.” But the events of the spring “reached a degree of seriousness that caused me to feel it was my duty to take steps to rectify the situation,” in which the “reputation of Cornell was being seriously menaced.” One possibility involved “putting you in as Chancellor and finding an understudy who would have charge of relationships with the faculty, the students, and the alumni. The areas of most serious discord.” Happily, Upson wrote, with the installation of Summerskill, and the realization “that you were leaving him completely alone, permitting him to handle the whole matter,” such an intervention proved unnecessary. Reassured, Upson “deeply regretted succumbing to the trustee pressure” and felt that there was no longer any justification for board interference, since it was evident that “[you had decided to] delegate responsibilities and . . . discarded your offensive operational methods.” He concluded with “a sincere hope my confidence is going to be justified.”