All Bohemian Roads lead to Oregon.

John

Glenwood and George Miller

Posted on February 4, 2019 by Royal Rosamond Press

I propose a newspaper museum for the New Glenwood, and the naming of the George Miller Highway from Florence to Winnemucca. I would like to see Glenwood renamed Fairmont, after the city that was swallowed by Eugene.

Elizabeth Maude “Lischen” or “Lizzie” Cogswell married George Miller. Lizzie was the foremost literary woman in Oregon. On Feb. 6, 1897, Idaho Cogswell, married Feb. 6, 1897, Ira L. Campbell, who was editor, publisher and co-owner (with his brother John) of the Daily Eugene Guard newspaper. The Campbell Center is named after Ira.

The Wedding of John Cogswell to Mary Frances Gay, was the first recorded in Lane County where I registered my newspaper, Royal Rosamond Press. Idaho Campbell was a charter member of the Fortnightly Club that raised funds for the first Eugene Library. Joaquin Miller was the editor of Eugene’s first newspaper the Democratic Register, and the Eugene City Review.

George Melvin Miller was a frequent visitor to ‘The Hights’ his brothers visionary utopia where gathered famous artists and writers in the hills above my great grandfather’s farm. The Miller brothers promoted Arts and Literature, as well as Civic Celebrations. Joaquin’s contact with the Pre-Raphaelites in England, lent credence to the notion that George and Joaquin were Oregon’s Cultural Shamans. Joaquin took part in the City Beautiful movement. George platted the city of Florence and Fairmont that was located next to Franklin Street. George was the promoter of a highway from Crescent City to Winnamucca, that was going to be a National Highway to New York. With new highways, I am promoting the Florence to Winnamucca route that traverses the Fremont Highway, named after the ‘Pathfinder’ who explored and mapped the Oregon Territory.

John Presco

Oregon Route 31 is a state highway in the U.S. state of Oregon that runs between the Central Oregon cities of La Pine and Lakeview. OR 31 traverses most of the Fremont Highway No. 19 of the Oregon state highway system,[2] named after John C. Frémont. The entire length of OR 31 is part of the Outback Scenic Byway, though the byway extends further south beyond the end of OR 31, to the California border.

Stepping Into History

Posted on February 5, 2019 by Royal Rosamond Press

Last night, when I started walking towards the podium at the Springfield City Hall meeting, I felt faint, and almost stumbled. It was like I had been at sea for a year, and when I stepped on to solid ground, I still had my sea legs. My voice faltered when I spoke. I realized the gravity of the moment. There was the Mayor of Springfield before me with her ears at ready. She wanted to hear what I have to say. I was, shocked! I have had some fierce rejection.

I now felt uneasy, because I was not prepared for what I was doing. In promoting the history of two men, I am promoting myself. This has always been difficult for me because I suffer from extreme low self-esteem. You would not know it by reading this blog.

When I visited my friend Nancy at the Springfield Creamer located a few blocks away from where I told the City Council about Harry Lane, she suggested I write the history of the hippies because I could recall so much. I began to write The Gideon Computer which is about the last Bohemian-Hippie in the future. I hid behind a science fiction character named Berkeley Bill Bolagard, who took on the persona of Buffalo Bill. Bill was homeless, and spent most of his time in the Oakland Library.

Before going into the meeting, I googled Ina Colbrith because I was going to mention her in the three minutes I had to speak. I read that she worked on the history of the early California Writers. Her notes got burned up in a fire. I wondered if my grandfather was in those notes. Ina worked at the Oakland Library that was her baby she grew to hate because it took up so much of her time. She was not writing poems. Then I read she raised Joaquin Miller’s daughter. In the morning I read a genealogy George Miller recited to a reporter. George taks about his mother;s cooking, and his father’s sheep that he raised in Coburg, a small town seven miles north of Springfield, that did not exist until 1885. George Miller says Coburg got its name from Ananiah Lewis who came from Wales. George claims he was the first to sell cherries from a wagon in Eugene.

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/25743586/the_oregon_daily_journal/

Before the meeting, I spotted Niel Laudati across the room. I went up to him and we shook hands. He had commented we had not seen each other for awhile. I told him he has done a great job with downtown Springfield. We had talked in his office about two years ago. He was glad he had taken Ken Kesey away from Eugene, and would take more if he could. I wanted to slip Joaquin Miller in my presentation, but I was afraid I would overwhelm the Mayor and Council. Joaquin has credibility problems. It is said Joseph Lane got him the job as the editor of the Eugene City newspaper, and wrote pro-slavery articles. Did Joaquin know Polly also? Did she talk about her family dramas? Miller had lived with a Native tribe and had a child by a Squaw. Miller may have been compelled to be a pro-slavery writer. He had graduated from Columbia College in Eugene. He was a country hick and bumkin who grew up in a tiny town. He was the real McCoy. Ambrose Bierce and Bret Harte came from back East. They were City Slickers playing Cowboy writers.

There is a saying in AA; “Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water.” When Joseph Lane and his Confederate backer in Oregon lost the Civil War, much of their history was thrown out. I believe Ina Coolbrith reworked Joaquin’s Brand that he began to create for himself while in college. What is a college education for?

I suspect many Western authors were jealous of Miller’s history and credentials. His famous “posturing” was done in self-defense. When I read this paragraph last night, I knew the City of Springfield was ready to receive their Native Son, because, Coburg is nearer to Springfield, then to Eugene, and, Phil and Penny Knight don’t like old stuff. They love shiny new things. Bohemian are about working with old stuff. I am on the verge of declaring Coburg the birthplace of American Bohemianism. Did the Springfield Creamery milk their own cows?

“Yet for all his posturing, Joaquin Miller, who took the name “Joaquin” in a fit of indignity over San Francisco’s mockery of his poem “Joaquin Marietta,” was the most forceful literary personality to emerge in 19th century California. Ironically, this poet so widely regarded as a fraud is frequently acknowledged as the first authentically Western voice; as a writer whose bullish attempts to body forth the spirit of the Sierras prefigured many great Californian writers to follow, including John Muir, John Steinbeck, Mary Austin, Gary Snyder and Robinson Jeffers. In his study Archetype West, the Bay Area poet William Everson cites Miller’s autobiographical fiction, Unwritten History: Life Among the Modocs, as the “inception point to the Western archetype,” claiming that in its ambitious fusion of myth, fact and nature, Miller “emerges permanently as the West’s first literary autochthon.”

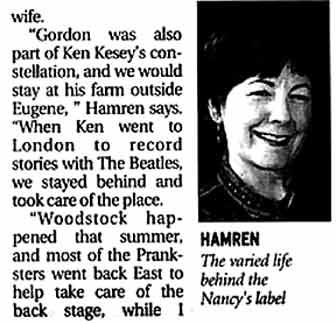

Thanks to Nancy Hamren, I am a writer and a historian. Berkeley Bill Bolagard has come of age, and, lives in Springfield Oregon. Nancy lived with Gordon, the brother of Mountain Girl, on the Kesey Farm in Pleasant Hill which is about eight miles from Springfield. Nancy and I grew up in Oakland and have compared Ken to Joaquin.

The discovery I made this morning that the Lane family is kin to the Hart family of Kentucky, who I am kin to via Senator Thomas Hart Benton, makes me a historian of renown once my findings are published. I just talked to the City Recorder who is going to send me back the pages I gave the Mayor and Council to read. They will file the copies in the City Archives. Then there is talk about a new Springfield Library.

I just awoke from my old-man nap with the words I spoke to my friend Amy Oles ringing in my head.

“Ina is the Queen Bee of the Bohemians!”

Ina was one of four women admitted to the Bohemian Club. She was their librarian. Ina was working on the Literary History of Western Writers. Joaquin was a member. The librarain who helped me was from West Virginia and knew nothing about Oregon History. I told him to look at Ina.

“Is she connected with Springfield?” he asked.

Joaquin gave his half-breed daughter to Ian to raise and educate. Her name was Cal-Shasta. Joaquin’s mother, who raised her family in Coburg, came to live with her son in the Hights, where members of the Bohemian Club came to spread the ashes of the Poet of the Sierras. This is to say the Miller Family DNA, went to Oakland. Margaret De Witt-Miller of Coburg, was surrounded by Bohemians, who probably assisted in the care of the mother of the Miller brothers, and Cal-Shasta? Who else?

“Joaquin Miller dumps his daughter into Ina’s lap to raise along with supporting her niece, nephew and step brothers. Miller’s daughter, Calla Shasta turns out to be a bit of a hell-raiser.”

Did Joaquin try to drop Calle Shasta off on his brother, George, but, the Cogswell family, would have none of that. They were connected to the founders of the Eugene Register Guard. Out West magazine published my grandfather’s poems and short stories. That magazine was formerly The Overland Express. Who is trying to gather all the writers under one wing, the Wing of the Owl?

John Presco

President: Royal Rosamond Press

At a literary dinner on May 5, 1874, Coolbrith was elected honorary member of the Bohemian Club,[27] the second of four women so honored.[28] This allowed the members of the club to discreetly assist her in her finances.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breckinridge_family

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ken_Kesey

Pleasant Hill was the first white settlement in Lane County when Elijah Bristow settled in 1846.[2] He was the first of a party of four immigrants to settle, most recently from California. Also in the party was Eugene Skinner, Captain Felix Scott, and William Dodson. Dodson and Scott took up adjacent claims, Dodson to the southeast and Scott to the west of Bristow’s claim. Scott later abandoned and claimed opposite the mouth of the Mohawk River, some 7 miles (11 km) north of his previous claim. Skinner made his claim at what is now Eugene.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ina_Coolbrith

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hart_Benton_(politician)

It all began in the coffeehouses a couple of centuries or more ago in London where such institutions as media and insurance took on their modern forms, for better or for worse.

The coffeehouses had names like The Fifth Estate and Lloyd’s of London. They all shared something in common. They imbibed a highly seditious drink, a coffee brew from Turkey called Kaufy. Most folks regarded the potent new drink the same way police viewed pot in the coffeehouses of Los Angeles and San Francisco in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

After the Gold Rush, Bohemia and coffeehouses developed in San Francisco with such characters as Herman Melville and Mark Twain. The bohemian was the foundation of good writing in California, first in San Francisco and then in Los Angeles.

Mark Twain comes to Southern California through the Newhall pass. It was in this area gold was first discovered in 1842 in nearby Placerita Canyon, not 1848 near Sutter’s Mills in Sacramento, the usual first dating of the Gold Rush. Twain probably visited Southern California while exploring the original gold fields in the 1860s. In 1884, Charles Lummis published Tramp Across the Continent, describing his trip to Los Angeles. Lummis became a seminal figure in the development of Los Angeles bohemia. He was the first city editor of the Los Angeles Times, the first librarian, and as publisher of the The Land Of Sunshine which became Outwest in 1901, eventually became Jack London’s first publisher. 1901 was also the year John C. Van Dyke published his masterpiece about Southern California, The Desert, a brilliant description of the Mojave’s many different colors and attributes.

Bohemianism moved to Carmel after the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, and it was from Carmel the great bohemian migration to Los Angeles began. A good example of this is Ina Coolbrith, the Oakland librarian who served as Jack London’s mentor. She became involved in a romantic three-way with Mark Twain and Brete Harte. She grew up in Los Angeles when it was still a pueblo, then moved north. In the late 1920s, she came back to the city of the angels to visit Charles Lummis at his El Alisal all stone castle in the Arroyo, shortly before both died. Others involved in 1906 in Carmel and then Los Angeles included Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, Upton Sinclair and Mary Austin.

At the center of this group was California poet laureate George Sterling, who had lived at the Bohemian Club on the Russian River north of San Francisco. Sterling, the state’s poet laureate, was friends of all the bohemians, and he visited his friend Finn Frolich in Los Angeles in the 20s. Frolich built a sculptor studio there and dedicated it to his old friend Jack London. London had written about Frolich as a character in his book Martin Eden, published in 1906. It is no accident that the insides of London House, which still stands in an alley near the Paramount Studios on Melrose Avenue, looked like a ship, with its winding narrow stairs. There’s a bust of London on the house’s bow—Frolich did the same bust at Oakland Square and London’s Valley of the Moon.

We don’t think of Dreiser as a California writer, but he was here for quite a spell. He was so close to Sterling he took his beautiful wife to the Bohemian club on the Russian River and allowed Sterling to entertain and woo her by swimming naked in the river. He moved to L.A. in 1919. He had written Sister Carrie in 1900. In 1920, he began An American Tragedy in L.A. Upton Sinclair, author of The Jungle in 1906, spent time in Carmel but then moved to Southern California in 1916 and spent most of the rest of his life here. His novel Oil published in 1927, is his great Los Angeles book. Recently it was made into a movie called “And There Will Be Blood.”

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/terence-clarke/the-bohemians-of-san-fran_b_5644219.html

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/lionel-rolfe/london-house_b_3813640.html

JOAQUIN MILLER

Historical Essay

by Jim Fisher

Poet Joaquin Miller, in buckskin with guns

“[Miller] shouted platitudes at the top of his voice. His lines boomed with the pomposity of a brass band; floods, fires, hurricanes, extravagantly blazing sunsets, the thunder of a herd of buffaloes—-all were unmercifully piled up. And yet, even in its most blatant fortissimos, Miller’s poetry occasionally captured the grandeur of his surroundings, the spread of the Sierras, the lavish energy of the Western World.” —-Louis Untermeyer, Modern American Poetry; 1930.

Recalling Joaquin Miller, the erstwhile judge, horse-thief and argonaut of Grant County, Oregon, a local miner remarked briefly: “He used to write verses and read them to us—-we thought he was a little cracked.” The man who was to inspire Buffalo Bill to sport sombreros, buckskin and spurs is also noted for rhyming “teeth” with “Goethe,” and for claiming to have been born on the Indiana plains “in a covered wagon, pointing west.” Not the only deliberate fiction of his life, Miller also boasted to have lived among the Modoc Indian tribe, to have accompanied William Walker on a revolutionary trip to Nicaragua, and to have been rescued from a Shasta City prison by an Indian princess.

Yet for all his posturing, Joaquin Miller, who took the name “Joaquin” in a fit of indignity over San Francisco’s mockery of his poem “Joaquin Marietta,” was the most forceful literary personality to emerge in 19th century California. Ironically, this poet so widely regarded as a fraud is frequently acknowledged as the first authentically Western voice; as a writer whose bullish attempts to body forth the spirit of the Sierras prefigured many great Californian writers to follow, including John Muir, John Steinbeck, Mary Austin, Gary Snyder and Robinson Jeffers. In his study Archetype West, the Bay Area poet William Everson cites Miller’s autobiographical fiction, Unwritten History: Life Among the Modocs, as the “inception point to the Western archetype,” claiming that in its ambitious fusion of myth, fact and nature, Miller “emerges permanently as the West’s first literary autochthon.”

For a brief period in the late 1860s, Miller was associated with the literary group surrounding the San Francisco journals The Golden Era and The Overland Monthly, though the relation was largely attributable to his own tireless self-promotion. Editors such as Bret Harte, Ina Coolbrith and Joseph E. Lawrence received pages of unsolicited manuscript from the Oregon judge, who seemed undaunted by rejection. (One note from Bret Harte assesses Miller’s verse as exhibiting “a certain theatrical tendency and feverish exultation, which would be better kept under restraint.”) In the dedication to his second book of verse, Joaquin et al., Miller includes a forthright address, “To the Bards of the San Francisco Bay,” which failed to elicit much response. Nonetheless, it was at this time that Miller entered into friendships with poets Charles Warren Stoddard and Ina Coolbrith, the latter of whom agreed to care for his daughter when Miller, determined to find fame across the Atlantic, abandoned San Francisco for London in 1870.

Ina Coolbrith

Photo: courtesy Stephen Mexal

Charles Warren Stoddard

Photo: courtesy Stephen Mexal

It was in England, after setting a wreath fashioned by Coolbrith on the grave of Lord Byron, that Miller blustered into a critical reversal among “the most startling of all of literature.” After failing to find a publisher for his poems, Miller pawned his watch, scraped together the last of his savings, and anonymously printed one hundred copies of his Pacific Poems. The reviewers for the London press swallowed it hook, line and sinker. Here at last was a poet with “the supreme independence, the spontaneity, the all-pervading passion, and the prodigal wealth of imagery” of a bona-fide bard of the frontier. With the help of friends, Miller immediately arranged for a second printing, changing the title to the more masculine Songs of the Sierras—-and this time including his name. Up until this second edition, one London critic was of the opinion that the poet of Pacific Poems was Robert Browning, albeit in a sort of pioneer mood.

Almost overnight Miller was transformed from a virtually unknown poet to the representative bard of the West. He attended dinner parties with Tennyson, Arnold and the Pre-Raphaelites, reputedly even running around on all fours at one formal dinner attended by two mortified San Francisco expatriates, Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce. To the London literati, Miller became the incarnation of the frontier, the “great interpreter of America.” Yet back in San Francisco his reputation hardly changed: critics still refused to take him seriously, though indeed there was more attention devoted to debunking him than before. Bierce, always leading public opinion with an insult, asserted early on that Miller was guilty of “rewriting his life by reading dime novels.”

Apart from his outlandish dress, perhaps the most publicized of Miller’s eccentricities was his preference for a quill pen, which he said “fitted his mood” because it made “a big, broad track.” Unfortunately, he often failed to sharpen the instrument, rendering his script unreadable. Many recipients of his letters, including Walt Whitman, simply refused to respond. According to the San Francisco poet George Sterling, the handwriting was another carefully maintained pose. Sterling’s uncle managed a few acres in the Oakland Hills bordering on Miller’s land, and whenever there was business requiring written communication, such as the hiring of guards to block hikers from cutting Christmas trees on their property, Miller’s script was as legible as a bookkeeper’s.

It was on this property in the Oakland Hills that Miller spent the final decades of his life. Planting eucalyptus trees around his acreage, which he called the “Hights” (his own spelling), he tended to his widowed mother, consumed vast amounts of whiskey, hailed passing girls as “the One Fair Woman!” and managed to produce several novels and plays before his death in 1913. On a porch overlooking San Francisco, Miller regularly entertained members of a younger generation of San Francisco writers, including Jack London, Mary Austin, George Sterling and Isabel Fraser. He had become a kind of mentor, the “grand old poet” of the turn-of-the-century Piedmont crowd. It was a unique triumph, perhaps all the more remarkable in that Miller’s literary admirers—-as revealed in posthumous appreciations written by Sterling, London and others—-remained skeptical to the end of Miller’s strictly literary merits.

FURTHER READING:

Untermeyer, Louis. Modern American Poetry, 4th rev. ed. New York: Harcourt, Brace; 1930.

Everson, William. Archetype West. Oyez Press, 1976.

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence and Nancy Peters. Literary San Francisco. Harper and Row, 1980.

Miller, Joaquin. Unwritten History: Life Among the Modocs. Orion Press, 1972.

Sterling, George. “Joaquin Miller.” American Mercury. February, 1926; p. 220.

Reblogged this on Rosamond Press and commented:

My grandfather, Royal Rosamond, belonged to the Mark Twain Society.