Did a Princess of the Scots marry into the family that owned the Shroud of Turin? Was Margaret aware there were Knights Templar in her lineage? She was a Queen of the House of Bourbon – and Stewart? I have proven the Rougemont Templars owned the Shroud. Is Margaret close kin of William and Harry via their mother?

She is kin to Guillaume de Beaujeu, the Grand Master of the Knights Templar, who was the cousin of Louis IX St. Louis and Charles of Anjou who were Crusaders. Of course she knew of the exploits of these royal men, and the Knights Templar.

Jon Presco

http://detyre.tripod.com/Articles/DBJ.html

William de Beaujeu was elected in1273. He had impeccable connections, as he was the cousin of Louis IX (St. Louis) and Charles of Anjou, both the most powerful of the European lords that could influence a crusade. After being appointed Master of the Temple, he joined Charles of Anjou in his lands in Sicily, then onward to France, answering the summons to attend the Second Council of Lyons, called by Pope Gregory X. He had high hopes of seeing a call for another crusade, and to learn the state of the Holy Land.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guillaume_de_Beaujeu

ttps://www.geni.com/people/Louis-de-Beaujeu-I/6000000003827781088

Jon Presco

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Stewart,_Dauphine_of_France

Jean de Montagu Capet, sire de Sombernon 1341-1410

| \

| ¯¯¯¯¯| 5_ … …

|–1_ Jeanne de Montagu Capet 1366-1426

| 24_ Louis I, seigneur de Beaujeu †1295

| _____| 12_ Guichard VI le Grand, seigneur de Beaujeu

| Father | Louis XI de Valois-Orleans , King of France (1461 (1423-1483) |

| Mother | Princess of Scots Margaret Princess of Scots (1424-) |

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

In 1429, young Louis found himself at Loches in the presence of Joan of Arc, fresh from her first victory over the English at the Siege of Orléans,[3] which initiated a turning point for the French in the Hundred Years War. Joan later led troops in other victories at the Battle of Jargeau and the Battle of Patay.[6] Although Joan was unable to liberate Paris during her lifetime, the city was liberated after her death, and Louis and his father Charles VII were able to ride in triumph into the city on 12 November 1437.[7] Nevertheless, Louis grew up aware of the continuing weakness of the French nation. He regarded his father as a weakling, and despised him for this.

Margaret Stewart of Scotland.[8]

On 24 June 1436, Louis met Margaret of Scotland, daughter of King James I of Scotland, the bride his father had chosen for diplomatic reasons.[9] There are no direct accounts from Louis or his young bride of their first impressions of each other, and it is mere speculation whether they actually had negative feelings for each other. Several historians think that Louis had a predetermined attitude to hate his wife. But it is universally agreed that Louis entered the ceremony and the marriage itself dutifully, as evidenced by his formal embrace of Margaret upon their first meeting.

Louis’s marriage with Margaret resulted from the nature of medieval royal diplomacy and the precarious position of the French monarchy at the time. The wedding ceremony — very plain by the standards of the time — took place on the afternoon of 25 June 1436 in the chapel of the castle of Tours and was presided over by Renaud of Chartres, the Archbishop of Reims.[10] The 13-year-old Louis clearly looked more mature than his eleven-year-old bride, who was said to resemble a beautiful doll, and was treated as such by her in-laws.[10] Charles wore “grey riding pants” and “did not even bother to remove his spurs”.[10] The Scottish guests were quickly hustled out after the wedding reception, as the French royal court was quite impoverished at this time. They simply could not afford an extravagant ceremony or to host their Scottish guests for any longer than they did. The Scots, however, saw this behaviour as an insult to their small, but proud, country.[11]

Following the ceremony, “doctors advised against consummation” because of the relative immaturity of the bride and bridegroom. Margaret continued her studies, and Louis went on tour with Charles to loyal areas of the kingdom. Even at this time, Charles was taken aback by the intelligence and temper of his son. During this tour, Louis was named Dauphin of France by Charles, as was traditional for the eldest son of the king.[11] The beautiful and cultured Margaret was popular at the court of France, but her marriage to Louis was not a happy

Crusading[edit]

When Louis was 15, his mother brought an end to the Albigensian Crusade in 1229 after signing an agreement with Count Raymond VII of Toulouse that cleared the latter’s father of wrongdoing.[10] Raymond VI of Toulouse had been suspected of murdering a preacher on a mission to convert the Cathars.[11]

Louis went on two crusades, in his mid-30s in 1248 (Seventh Crusade), and then again in his mid-50s in 1270 (Eighth Crusade).

Seventh Crusade[edit]

Engraving representing the departure from Aigues-Mortes of King Louis IX for the Seventh Crusade (by Gustave Doré).

Equestrian statue of King Saint Louis at the Sacré-Cœur

In 1248 Louis decided that his obligations as a son of the Church outweighed those of his throne, and he left his kingdom for a six-year adventure. Since the base of Muslim power had shifted to Egypt, Louis did not even march on the Holy Land; any war against Islam now fit the definition of a Crusade.[12]

Louis and his followers landed in Egypt on 5 June 1249 and began his first crusade with the rapid capture of the port of Damietta.[12][13] This attack caused some disruption in the Muslim Ayyubid empire, especially as the current sultan, Al-Malik as-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub, was on his deathbed. However, the march from Damietta toward Cairo through the Nile River Delta went slowly. The rising of the Nile and the summer heat made it impossible for them to advance and follow up on their success.[14] During this time, the Ayyubid sultan died, and the sultan’s wife Shajar al-Durr set in motion a sudden power shift that would make her Queen and eventually place the Egyptian army of the Mamluks in power. On 6 April 1250 Louis lost his army at the Battle of Al Mansurah[15] and was captured by the Egyptians. His release was eventually negotiated in return for a ransom of 400,000 livres tournois (at the time France’s annual revenue was only about 1,250,000 livres tournois) and the surrender of the city of Damietta.[16]

Louis IX was taken prisoner at the Battle of Fariskur, during the Seventh Crusade (Gustave Doré).

Four years in Palestine[edit]

Following his release from Egyptian captivity, Louis spent four years in the Latin kingdoms of Acre, Caesarea, and Jaffa, using his wealth to assist the Crusaders in rebuilding their defences[17] and conducting diplomacy with the Islamic powers of Syria and Egypt. In the spring of 1254 he and his army returned to France.[12]

Louis exchanged multiple letters and emissaries with Mongol rulers of the period. During his first crusade in 1248, Louis was approached by envoys from Eljigidei, the Mongol military commander stationed in Armenia and Persia.[18] Eljigidei suggested that King Louis should land in Egypt, while Eljigidei attacked Baghdad, to prevent the Saracens of Egypt and those of Syria from joining forces. Louis sent André de Longjumeau, a Dominican priest, as an emissary to the Great Khan Güyük Khan (r. 1246-48) in Mongolia. Güyük died before the emissary arrived at his court, however, and nothing concrete occurred. Instead his queen and now regent, Oghul Qaimish, politely turned down the diplomatic offer.[19]

Louis dispatched another envoy to the Mongol court, the Franciscan William of Rubruck, who went to visit the Great Khan Möngke (1251-1259) in Mongolia. He spent several years at the Mongol court. In 1259, Berke, the ruler of the Golden Horde, westernmost part of the Mongolian Empire, demanded the submission of Louis.[20] On the contrary, Mongolian Emperors Möngke and Khubilai‘s brother, the Ilkhan Hulegu, sent a letter seeking military assistance from the king of France, but the letter did not reach France.[21]

Eighth Crusade[edit]

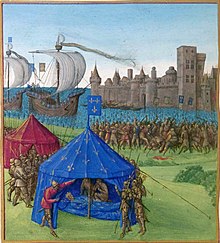

Death of Saint Louis: On 25 August 1270, Saint Louis dies under his fleurdelisé tent before the city of Tunis. Illuminated by Jean Fouquet, Grandes Chroniques de France (1455–1460)

In a parliament held at Paris, 24 March 1267, Louis and his three sons took the cross. On hearing the reports of the missionaries, Louis resolved to land at Tunis, and he ordered his younger brother, Charles of Anjou, to join him there. The crusaders, among whom was Prince Edward of England, landed at Carthage 17 July 1270, but disease broke out in the camp. Many died of dysentery, and on 25 August, Louis himself died.[17][22]

Patron of arts and arbiter of Europe[edit]

Louis’ patronage of the arts drove much innovation in Gothic art and architecture, and the style of his court radiated throughout Europe by both the purchase of art objects from Parisian masters for export, and by the marriage of the king’s daughters and female relatives to foreign husbands and their subsequent introduction of Parisian models elsewhere. Louis’ personal chapel, the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, was copied more than once by his descendants elsewhere. Louis most likely ordered the production of the Morgan Bible, a masterpiece of medieval painting.

Pope Innocent IV with Louis IX at Cluny

During the so-called “golden century of Saint Louis”, the kingdom of France was at its height in Europe, both politically and economically. Saint Louis was regarded as “primus inter pares”, first among equals, among the kings and rulers of the continent. He commanded the largest army and ruled the largest and wealthiest kingdom, the European centre of arts and intellectual thought at the time. The foundations for the famous college of theology later known as the Sorbonne were laid in Paris about the year 1257.[14] The prestige and respect felt in Europe for King Louis IX were due more to the attraction that his benevolent personality created rather than to military domination. For his contemporaries, he was the quintessential example of the Christian prince and embodied the whole of Christendom in his person. His reputation for saintliness and fairness was already well established while he was alive, and on many occasions he was chosen as an arbiter in quarrels among the rulers of Europe.[6]

Shortly before 1256, Enguerrand IV, Lord of Coucy, arrested and without trial hanged three young squires of Laon whom he accused of poaching in his forest. In 1256 Louis had him arrested and brought to the Louvre by his sergeants. Enguerrand demanded judgment by his peers and trial by battle, which the king refused because he thought it obsolete. Enguerrand was tried, sentenced, and ordered to pay 12,000 livres. Part of the money was to pay for masses in perpetuity for the men he had hanged.

In 1258, Louis and James I of Aragon signed the Treaty of Corbeil, under which Louis renounced his feudal overlordship over the County of Barcelona and Roussillon, which was held by the King of Aragon. James in turn renounced his feudal overlordship over several counties in southern France including Provence and Languedoc. In 1259 Louis signed the Treaty of Paris, by which Henry III of England was confirmed in his possession of territories in southwestern France and Louis received the provinces of Anjou, Normandy (Normandie), Poitou, Maine, and Touraine.[4]

STORY OF MASTER WILLIAM DE BEAUJEU, the twenty-first Master of the Temple, frequently reads like the story of Cassandra, the prophetess of the Trojans. Whenever de Beaujeu would warn the people of the now-waning crusader states of impending disaster, he was treated with scorn and derision, and called a coward and traitor. The warnings and pleas he would give would, like in Cassandra’s case, fell upon deaf ears.

I. ORIGINS

William de Beaujeu was elected in1273. He had impeccable connections, as he was the cousin of Louis IX (St. Louis) and Charles of Anjou, both the most powerful of the European lords that could influence a crusade. After being appointed Master of the Temple, he joined Charles of Anjou in his lands in Sicily, then onward to France, answering the summons to attend the Second Council of Lyons, called by Pope Gregory X. He had high hopes of seeing a call for another crusade, and to learn the state of the Holy Land. He did not like what he found. The Holy Land was in constant fear of attack from the new Egyptian sultan, Malik Rukn ed-Din Baibars, and while the Pope was willing to offer whatever help needed, he was, ultimately, ignored. The ravages against the much-reduced Kingdom of Outremer continued.

When de Beaujeu arrived in the Holy Land in 1275, he learned that the local barons were happy that there was no forthcoming crusade. It seemed that any upcoming crusade would interfere with the profitable trading that the crusader states had with the major Muslim merchant cities. Because of this lucrative trading, the barons did not believe that the Muslims would invade and destroy the valuable port cities that funneled the riches of the East to Europe. Besides, the barons were too busy fighting with one another over the ever-shrinking real estate of Outremer.

II. THE BEGINNING OF THE END

But Master William inherited a vast network in the Muslim lands as well. He had the Order’s banking network extended to cities like Cairo, Alexandria, Damascus, and other cities. He also had informants in all of the courts of Islam, highly placed and handsomely paid for whatever information they might gather. The Templars would disseminate any information gathered, insuring its accuracy, and then used the information in whatever way would best further Templar policy in the East. If the nobles of the kingdom had but listened to de Beaujeu, perhaps there would have been a chance.

Because of this network, de Beaujeu learned of the death of the sultan Baibars, killed when he invited a rival named al-Qahir, a descendant of Saladin, to a dinner party. He slipped poison into al-Qahir’s cup, and the cups were switched somehow. Baibars inadvertently poisoned himself, and died on the evening of 1 July, 1277. He was succeeded by Kala’un, who sought a peace-treaty with the crusaders to free up his forces from the Mongol threat to the Sultanate of Egypt. Master William signed this treaty in May of 1281.

Unfortunately, the crusaders were more concerned with the threat posed by the Mongol Ilkhanate of Persia. In 1281 the Mongol Ilkhan launched a major offensive against the Sultanate of Egypt. Kala’un extended the treaty of 1281 to last yet another ten years. But instead of preparing for the onslaught that was to come, the crusader barons and the Italian merchant contingents continued to cut-throat each other when, in 1289, Kala’un returned. It seems the leaders of the various factions in Tripoli invited Kala’un to intervene in their disputes. To their dismay, Kala’un showed up with an army in March of 1289.

De Beaujeu learned of Kala’un’s true intentions by a member of the Mamluk court, and official in their pay named al-Fakhri. According to al-Fakhri, the Sultan was sending a large army to Syria for an attack on Tripoli, and de Beaujeu warned the Tripolitan rulers. His information was met with scorn and abuse. De Beaujeu sent the Marshal of the Temple, Geoffrey de Vendac with a contingent of Templars to help with the defense of the city. The leaders of the city came to believe de Beaujeu after riders reported a massive Muslim army was marching right for Tripoli. King Hugh of Cyprus sent a group of knights under his brother Amalric, and a group of French mercenaries were sent from Acre. Soon, the city of Tripoli was surrounded by thousands of Muslim soldiers, and the walls were soon under heavy bombardment from nineteen huge mangonels. One of the corn-er towers crumbled under the hail of block-bursting twohundred pound stones, and the Italian merchant soldiers were the first to flee, with all the ships that remained. When Kala’un learned of their flight, he ordered a general attack on all points of the wall, and soon, Mamluk soldiers were dropping in from all points of the walls. They fought their way to the gates, and the slaughter began.

Amalric of Cyprus left with the remainder of his troops and the Templar Marshal de Vendac, leaving the surviving Templars to fight on to the death. All that remained of the citizens of Tripoli were the slaves wailing their misery, and the bodies rotting in the ruins, for Kala’un ordered the city and its walls torn down De Beaujeu and the Templars lost a core of trained soldiers they could ill afford to lose.

Those crusaders remaining in the one major city left to them, Acre, were terrified, fearing that they were next. It was with relief, then that they learned that Kala’un wanted to sign another ten-year truce with the remnants of the kingdom. The crusader barons signed with alacrity, though Hugh of Cyprus believed that Kala’un would break his treaty with them at the slightest excuse. He knew that the only hope of survival the kingdom of Outremer had would be in a major crusade with the combined armies of the crowned heads of Europe.

Hugh sent envoys to stress the need for another Crusade, and the envoys received mealy-mouthed promises and no concrete dates for the arrival of crusader armies. The only real help the kingdom of Outremer got was a group of unemployed mercenaries from Northern Italy. This undisciplined rabble consisted of mostly men who would sell their mothers for a coin, murderers, rapists, excommunicated soldiers and troublemakers. As these men saw things, they were there to kill Muslims and be well paid for their services. Inevitably, they got into a drunken brawl with some Muslim citizens in Acre, a brawl that spread until it became a large-scale riot. The killing and looting was only put down when the entire contingent of the Templars and Hospitallers were brought in.

The surviving Muslims went straight to Kala’un in Cairo, to call for vengeance. Kala’un was outraged, and demanded the surrender of the culprits, a demand that was was rejected. Once again, al-Fakhri warned Master William de Beaujeu that if these demands weren’t met, the Sultan of Egypt would invade and utterly destroy Acre.

De Beaujeu pleaded with the leaders of Acre to comply, but was met with angry shouts of defiance. “How dare you even consider turning Christian men over to the paynim,” the leaders demanded, “It is clear you love money more than you love Christ to consider such a cowardly way!”

Undaunted, de Beaujeu sent Templar envoys to Egypt to negotiate for some type of compromise. Kala’un’s terms were that the Templars could buy the lives of the people of Acre for a ransom of Venetian gold zecchines, one coin for each living soul. De Beaujeu presented this proposal to the city’s leaders, and once more he was shouted down with insults and abuse. Some days later, news came from Cairo that Kala’un was dead. He was succeeded by his son, al-Ashraf Khalil, who was just as committed to the destruction of Acre as was his father.

Concerned, the leaders of Acre send an ambassadorial party to Cairo in hopes of renewing the treaty between the two nations. The ambassadors were killed, giving an unmistakable message as to his intentions, but still the city did not prepare for the assault that was bound to come. The city was caught up in the endless stream of frenzied social activities that most decadent cultures indulge in before their fall.

In March of 1291 the Sultan of Egypt began his march on the truncated kingdom of Outremer. When the leaders and citizens heard the attack would really take place, the reaction was panic. Instead of abuse and cries of cowardice, the people pleaded with the Master of the Temple to save the city of Acre. De Beaujeu marshaled his forces alongside those of the Hospitallers, Teutonic Knights and the Order of St. Lazarus. The Venetians and Genoese mustered their forces, along with the city garrison and a contingent of Latin Cypriot knights, commanded by Amalric of Cyprus, and a small unit of English knights, under Otho de Grandison, a Swiss knight in service to King Edward I. However their numbers were wholly inadequate for the struggle to come, and together they could only scrape together eight hundred knights and around fourteen thousand men-at-arms. Al-Ashraf’s army numbered over one hundred sixty thousand.

Acre was built on a peninsula jutting into the Mediterranean Sea, and was shaped like a heater-shield. The south and westward edges were in the sea, and contained a natural harbor. The northern and eastern sections were encircled by two stone walls, the outer walls protected by ten great towers, the inner walls were protected by the largest tower, called the Accursed Tower.

III. THE DIE IS CAST

On 6 April 1291, the siege began, with the sound of stone cracking on stone, the roar of fireballs shot over the walls into the city and the mean hum of thousands of arrows. Two huge catapults, the Victorious and the Furious battered the north wall. In addition, ninety-two mangonels kept a steady stream of stones and Greek Fire pouring onto the garrison, while engineers dug tunnels day and night to undermine the towers of the outer wall.

De Beaujeu and Templars, stationed on the northern sector, felt their morale suffer from the constant bombardment that kept them under cover. They knew that they could not long endure sitting without striking a single blow, so they came up with a plan. De Beaujeu led three hundred of them in a charge from the St. Lazarus Gate to capture and destroy the Victorious on the evening of 15 April.

Uttering their battle cries, they charged through the Muslim camp, but in the darkness the horses tripped on the tent ropes that zigzagged the camp, unhorsing several knights. The Muslims, alerted by the noise, killed the dismounted knights where they fell. The attack was a dismal failure.

The Hospitallers tried their luck later that month with a similar attack, but the Muslim army expected that they would try again. They placed torches and bonfire piles about the camp, and lit them when the attack came, making the camp as bright as day. The Hospitallers, their attack robbed of the element of surprise, fled back to the city with heavy losses. The garrison tried no further evening raids.

King Hugh of Cyprus joined the city garrison on 4 May, bringing two thousand soldiers with him. Knowing that the city walls would not hold up under the pounding for much longer, de Beaujeu urged Hugh to send two knights to the Muslim camp under a flag of truce to discuss terms. One of the knights was a Templar, Guillaume de Cafran, who was fluent in Arabic. Al-Ashraf received them before his tent, and offered to allow the inhabitants to leave unmolested if they would surrender the city.

At that moment, a huge catapult stone launched from the city landed just short of the sultan’s tent. Believing that the crusaders were negotiating in bad faith, he nearly killed them by his own hand, but was restrained by his officers, who suggested the envoys leave.

IV. “SEIGNEURS, JE NE PLUS, CAR JE SUY MORT–VEES LE COUP.”

Two weeks after the failed negotiations, Kala’un’s miners had finally reached their objective, and had undermined a large stretch of wall. They set fire to the supporting timbers, and soon the towers began to fall into rubble. The crusaders fell back to the inner wall, and the Muslims forced the attack on all sections of the wall. They took the Accursed Tower, drove the crusaders from the wall and opened the gates. Thus began an orgy of slaughter.

Master William de Beaujeu fell attempting to retake the crumbling Accursed Tower, shot under the armpit with an arrow that hit a weak spot of his hauberk. While the garrison cursed him for his cowardice, he told them, “My lords, I can do no more, for I am dead. See the wound.” His soldiers took him to the Templar enclave in the south- west of the city, where he later died. The Hospitaller master was carried away to his galley, screaming for his men to put him down and insisting he could still fight. King Hugh and his brother fled with their garrison, and so did Otho de Grandison with the remnant of his contingent. The Venetians and the Genoese fled, but not before loading their galleys with merchandise, leaving people weeping by the docks. The only active crusader fighting force was the Templars in their tower by the sea. They died later, fighting to the last.

V. CONCLUSION

Master William de Beaujeu was the last Master of the Temple to give his life in protection of the Holy Places of Palestine. Perhaps it was a good thing that he would not live to see what would become of the order he gave so much for. The Templars who would survive him were a demoralized and dejected group. In subsequent years they, along with all the other military orders, came under increasing attack, and (ironically) were blamed for the loss of the Kingdom of Outremer.

Ultimately, the Catholic Church that they fought and died to protect turned on them, driven by the greed of King Phillip IV of France, who had nearly the entire Order of the Temple in France arrested and charged with heresy, sodomy, simony, idolatry and other trumped-up charges. These charges (and the adverse publicity that followed) led to the suppression of the Order in 1314 by Pope Boniface V, and the death of the last Master of the Temple. Jacques de Molay, along with Geoffrey de Charnay, Preceptor for Normandy, were burned at the stake, crying their innocence and that of the Order to the very last.

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Leave a comment