When I met with Belle Burch, I asked her to co-author my biography ‘Capturing Beauty’ because I wanted a feminine perspective, and, a female audience that would be more open to woman’s message. Here is Miriam Peskowitz saying that Jewish Weaving Stories carried on the teaching of the Sages and Rabbis after the fall of the temple, after Queen Helena – whom I title Sleeping Beauty – lost to the Roman slave masters.

When I met with Belle Burch, I asked her to co-author my biography ‘Capturing Beauty’ because I wanted a feminine perspective, and, a female audience that would be more open to woman’s message. Here is Miriam Peskowitz saying that Jewish Weaving Stories carried on the teaching of the Sages and Rabbis after the fall of the temple, after Queen Helena – whom I title Sleeping Beauty – lost to the Roman slave masters.

My surname was originally Preskowitz. I suspect I am of Jewish descent. I have titled myself a Rabbi in this blog. Consider the labyrinth were Beautiful Rosamond lived, and the clue of the red thread that led Queen Eleanor to her.

Jon Presco

https://rosamondpress.com/2012/10/01/the-sons-of-the-nazarite-queen-war-with-rome/

https://rosamondpress.com/2013/07/11/clue-of-the-rose-thread/

Miriam Peskowitz offers a dramatic revision to our understanding of early rabbinic Judaism. Using a wide range of sources—archaeology, legal texts, grave goods, technology, art, and writings in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, and Latin—she challenges traditional assumptions regarding Judaism’s historical development.

Following the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple by Roman armies in 70 C.E., new incarnations of Judaism emerged. Of these, rabbinic Judaism was the most successful, becoming the classical form of the religion. Through ancient stories involving Jewish spinners and weavers, Peskowitz re-examines this critical moment in Jewish history and presents a feminist interpretation in which gender takes center stage. She shows how notions of female and male were developed by the rabbis of Roman Palestine and why the distinctions were so important in the formation of their religious and legal tradition.

Rabbinic attention to women, men, sexuality, and gender took place within the “ordinary tedium of everyday life, in acts that were both familiar and mundane.” While spinners and weavers performed what seemed like ordinary tasks, their craft was in fact symbolic of larger gender and sexual issues, which Peskowitz deftly explicates. Her study of ancient spinning and her abundant source material will set new standards in the fields of gender studies, Jewish studies, and cultural studies.

M. Peskowitz and L. Levitt, Judaism Since Gender (Routledge, New York: 1997) pp. 229.

https://rosamondpress.com/2013/09/27/marie-de-france-is-fair-rosamond-the-sleeping-beauty/

https://rosamondpress.com/2013/02/01/sleeping-beauty-heart/

https://rosamondpress.com/2014/12/01/an-appeal-to-belle-burch/

https://rosamondpress.com/2012/12/06/capturing-beauty-the-prick/

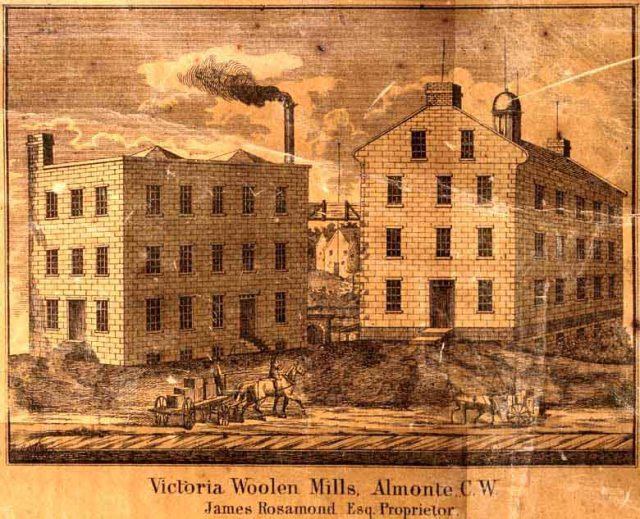

Bennett Rosamond and I look alike. At the Mill I asked our guide, Bill, about a “weaver’s needle”. He showed me an object that could not have been what the Rougemonts wore on Crusade. We talked to five elderly women in the weaving room, and they concluded the needle was a spindle. I found myself in a living Fairy Tale, and Templar Legend.

On the floor of the mill was wool. We were given a sample to touch. The woman next to me asked if we could keep it, and gave half to me. See photo above of my piece of yarn.

Here is a post made October 3, 2011

The Rosenmund cote of arms contains a cross. Only a family that went on crusade can put a cross on their shield. This cross is made up of a weaving hook, according to the Rosamond family genealogists, and was worn as a tunic pin by the Rougemont Crusaders. What this cross is, is a spindle. The Knights Templar of Fontenotte had a spindle on the marker outside their chapel where in the place of roses, they have two camels that represent the Outremer, the Kingdom of God that was lost to Islam. It is time to awaken that kingdom from a long sleep.

The Templar cross is a spindle viewed from the top. We see it laid down on the monument. This is my revelation after attending a weavers convention at the Lane County fairgrounds where I saw a spindle that looked like a cross. I talked to an expert who was present, and he said this cross design had been around before the Crusades. This is evidence my Rosamond/Rougemont ancestors were Knights Templar.

Above is the Rosamond cote of arms that has a cross made of a weavers needle on a mount with two flowers. You can not have a cross in your cote of arms unless your kindred went on crusade. Did the Lords of Rougemont and Florimont go on Crusade? I believe they went as Knights Templar.

The Rosamond family were weavers for countless generations. Surely we took interest in the story of Sleeping Beauty. Perhaps, it is a family yarn whose woof and weave connects us to the bloodline of the Swan Knight? Hans Ulrich Rosemond was a weaver. Ulrich means “wolf ruler’, and Hans is John.

A month into World War Two, German troops entered the city of Louvain and utterly destroyed it because freedom fighter were allegedly sniping at the Kaizer’s men. Atrocities were committed. Nuns were stripped naked in search of weapons. Citizens were herded off to concecration camps. Louvain College was burned to the ground along with four Art Colleges. One of them was the Falcon Art College of which my ancestor Godeschald Rosemondt was the Master. Was his artwork lost in the flames?

Above is a photo of Rosemondt’s book that he signs with a Rose and Mont. There is a Habsburg cote of arms and a emplem for the Falcon College. The Rosemondts were members of the Swan Brethren who wore a pen of a closed rose surrounded by thorns.

Here is the story of the Sleeping Beauty Princess named Rosamond and a beautiful city full of Artists and Thinkers that is destroyed because of the Kulturekumpf (cutlure war) The Kaizer is waging against Catholics. Louvain is a famous Cathlic University that was established in a Weaver’s Hall donated by another Godeschalk Rosemondt. Losing a Weaver’s Rebellion, many weaver families fled to England.

I just found out about the destruction of Louvain this morning. I believe much of the Rosemondt Family history was lost. I believe I was born to raise it from the ashes. I am The Rose of the World.

The cote of arms of Louvain depicts a open book with empty pages. Consider the Faun showing Ofelia the book of the Crossroads – the Rose Crossroads. The Louvain atrocity preceeds the atrocities of Franco against the Freedom Fighters of Spain, and the Jews of Germany. Louvain was a portal into the future, a bell that sounded a warning.

A Seer said I go each knight to a place the Rosicrucians discovered called ‘The Catherdral of the Souls’ where I have a reserved seat at a great wooden table. There is a hood figure standing behind because I am……..The One.

Awake and rise my dear Roses! Arise!

John Ulirch Rosemond

Copyright 2012

Peter Rosemond further reported

information from the Records Office in Basle that “before Basle the

family resided in Holland up to 1338, and it is said they descended

from the estate Rosemont, near Belfort, in France, where also the

village Rougemont is found.” A family coat-of-arms was registered

in Basle about 1537 when the first Hans became a resident there. A

reproduction of this coat-of-arms in the writer’s possession shows a

weaver’s crook conspicuously, and it will be remembered that in

Ireland our people were linen weavers and farmers, and that Edward,

the elder, was a weaver in this country. Peter Rosemond had seen in

print the letters from Erasmus to Gotschalk Rosemondt. He noticed

that a seal used by a Rosemont in Holland, bearing a jumping fox,

was like an emblem he had noticed in a wall of the house Rebleuten-

Zunft in Basle. This seal dated back to 1430, whereas the coat-of-

arms above mentioned dates from 1534, it seems.

https://rosamondpress.com/2012/12/06/capturing-beauty-the-prick/

When I was younger, I did not know. I thought that everyone fit neatly into the neutral category. “He” meant women and men, and “mankind” included all of humanity. Now, when I read my earlier work or when I read the books of our late and revered teacher, Abraham Joshua Heschel, I know what was meant, but I do not hear it the same way.

The feminist movement sharpened my ears and made it clear that “he” was a masculine, not an inclusive, pronoun. Feminist method also taught me that everyone, including myself, writes from within an autobiographical context. I am white, male, middle class, middle-aged, intellectual, Jewish, and heterosexual. I can really only speak for myself and, perhaps, for those like me. If I want to speak to others, I need to be much more consciously inclusive. Further, if I claim to speak for others, I need to be very careful that I know what I am talking about. Further, I need to be very cautious not to appropriate their voices. Laura Levitt was among the first to help me learn these lessons.

Now, Laura Levitt has, together with Miriam Peskowitz, published a book of essays on feminism as a method of reading and writing Jewish scholarship. Judaism Since Gender began with an excellent essay by Miriam Peskowitz and a series of questions by both editors which were sent to the contributors. Some wrote short responses and others more extended studies. The result is a series of essays which deal with feminism as a method, especially those by Miriam Peskowitz, Beth Wenger, Ellen Umansky, Riv-Ellen Prell, Sara Horowitz, and Laura Levitt. This grouping also includes a response by Rebecca Alpert which critiques the whole enterprise. (Is it an accident that this counter-essay is exactly in the middle of the book?)

The result also includes a series of essays which are feminist praxis, that is, they examine Jewish subjects using feminist methodology: Jesus (Susannah Heschel), women survivors of the shoah (Sara Horowitz), Maimonides (Susan Shapiro), New Testament studies (Amy-Jill Levine), rabbinic Judaism (Judith Baskin), ultraorthodox women (Tamar El Or), and sephardi women (Joëlle Bahloul). There are also two essays which use feminist methodology on subjects which are not directly concerned with role and place of women: Zionism (Laurence Silberstein) and Wissenschaft des Judentums (Robert Baird).

What, then, is feminist method as I understand it? It begins with the recognition that traditional scholarship organizes knowledge in ways that claim to be “objective” but which, upon closer analysis of language and analytic categories, reveal assumptions which privilege the perspectives of men, of the middle class, of heterosexuals, of the enlightenment as an ideology, and so on (3, 18-19). This does not happen in one sweeping attack but, like a backstitch, advances by looping backward. Thus, I began my own discovery of feminist method by examining so-called neutral pronouns. That led to a consideration of the tendency toward bipolar analysis, itself only one way of seeing the world, which characterizes certain modes of thinking practiced by men for many centuries. That, in turn, led to an analysis of the tendency to value universalization and resist particularization, again a praxis that is not absolutely good but a product of its own cultural environment. It also led me to see clearly the tendency to favor history over theology as a mode of discourse. The more I have traveled this path, the more I have come to see clearly the assumptions of language and culture inherent in all writing and reading.

One of the best tactics for exploring this critical view of the way one reads and writes is to ask the questions, where are the women’s voices in this passage? What are the ignored and the suppressed voices in this incident? In the beginning, I was tempted to “add women and stir,” that is, to talk about “women and …,” or “women in …,” or to add on a section dealing with women to the previously existing analysis or discussion. This “add women and stir” approach, popular as it was a decade ago, nonetheless reflects the basic assumption that something other than women is “normal” and women need to be “added.” This is hardly a responsible scholarly approach, nor is it ethically proper (18-22).

If I cannot simply “add women and stir,” what, then, constitutes the method of feminist scholarship? There are several ingredients. First, each one of us must grow to recognize that all scholarship, reading and writing, takes place in an autobiographical context. Everyone reads with, and writes with, assumptions; and each one of us must be honest about the assumptions of others and of oneself (215).

Second, each one of us must locate and name the assumptions in the reading and writing of others and of oneself. We must recognized the masculinist or feminist thrust of our language and analytic categories (23, 114, 153). To speak of “engendering” Judaism or Jewish studies, for instance, already presupposes that there is an existing normative gender — male (30). Each one of us must also locate and name those places where other assumptions are made: that the male pronoun denotes an area where gender and class do not count (79), that the enlightenment with its attendant assimilation was good and valuable because it would correct the wrong assumptions about Judaism made by non-Jews (86), that there are a set of “classic” texts that are the canon of Jewish civilization, that Hebrew is “better” than Yiddish (40-48), etc.

Third, each one of us must juxtapose new and old knowledges, setting the results of feminist scholarship next to the earlier studies. Whether the subject is women and men, or Jews and Jewishness, or Christianity, or the enlightenment, there is more than one way to construe the data on these subjects and more than one set of assumptions that motivates scholarship on these topics. Feminist method is committed to “problematizing” the older commitments and displaying the new commitments and insights (3). It is dedicated to asking, how did the old knowledge come to be knowledge in the first place? What is the story being told, who is telling it, and who benefits from the way it is told? (23-24).

Finally, feminist method is determined to ask, are we conscious of what we are doing? Have we fully explored the unstated assumptions, even in our own work? Have we been sensitive to the silenced voices, to the gaps in the various types of texts we study? Have we listened to what has not been said? And, have we responded to the inarticulated communication inherent in all presentation? (200-12). My own work tries, sometimes with greater or lesser degress of success, to embody this methodology.

Much of feminist method, it seems to me, derives from the work of Foucault whose presence hovers in this book. He was among the first to explore the relationship between power and knowledge. Knowledge is arranged by those who order it, and they have vested interests even where those interests are not evil. Whose interest is represented in this work of art? in this history? in this canon? in this law? Whose interest is served by this language? by these images and metaphors? These are the questions that have been developed quickly and effectively by feminism in relationship to women but which also have relevance for all “colonial” thinking which tries to imposed assumptions of one class or culture on others.

Miriam Peskowitz’s introductory essay, “Engendering Jewish Religious History” and Sara Horowitz’s essay, “Mengele, the Gynecologist, and Other Stories of Women’s Survival,” are very fine essays. The first sets forth the problematic of feminist method very clearly and the second embodies it with great sensitivity. Among the other fine essays in this book, everyone will have a favorite essay; my own is Susannah Heschel’s “Jesus as Theological Transvestite” (188-99). Drawing on queer theory, Heschel points out that heterosexuals are disoriented and uncomfortable with the transvestite, a person who dresses like the opposite sex. The transvestite disrupts the binary categories of male-female; he/she destabilizes the usual gender signs within which the rest of humanity lives. The transvestite is a “third category,” one that does not fit the binary others.

Without being disrespectful in the least, Heschel goes on to point out that Jesus is both fully a Jew and also the first Christian. He is, thus, both and yet neither. He bridges two worlds and, as such, disrupts and destabilizes the firm boundaries that divide Jews and Christians, Judaism and Christianity. As Heschel so aptly puts it, “Jews dress him [Jesus] as a rabbi and Christians dress him as a Christian” (192). I suppose I had always known this but it was only with the benefit of a feminist use of queer theory that I was able to see it so clearly and also to account for the disquiet which I and many others feel when we deal with the person of Jesus.

This model of understanding Jesus illuminates several other scholarly attitudes and postures. It accounts for Christian scholars who gladly acknowledge Jesus’ Jewishness but vilify the Judaism of which he was a part, specifically Pharisaic Judaism and rabbinic Law. Such a stance allows the reader-writer to affirm Jesus’ Jewishness and yet see him as one who “transcended” or “purified” the tradition of which he was a part, thus rendering it — and the Christianity to which such reader-writers adhere — “better.” It also helps us understand the fear Jews have of Jesus for, if a good Jew can become a Christian, so could any Jew. And, the fear Christians have of Jews for, if a good Christian can “slide into the morass of Jewishness,” so can any Christian. Finally, this analysis also accounts for the deep ambivalence in both Jewish and Christian circles toward Jewish scholars who write on Jesus. For the former, such a Jew is somehow disloyal; for the latter, such a person is a trespasser. This is not unlike the man who writes about women, or the woman who writes about men. The “very gaze of the scholarly eye” is destabilized.

Judaism Since Gender is a book that should be used in all graduate courses. It orients even as it disorients, and that is part of the work of all true scholarship.

This appeared in Nashim, 2:173-77.

http://www.hebrewhistory.info/factpapers/fp018_carpets.htm

“Simon held the upper city, and the great walls as far as Cedron, and as much of the old wall as bent from Siloam to the east, and which went down to the palace of Monobazus, who was king of the Adiabeni, beyond Euphrates; he also held the fountain, and the Acra, which was no other than the lower city; he also held all that reached to the palace of queen Helena, the mother of Monobazus; but John held the temple, and the parts thereto adjoining, for a great way, as also Ophla, and the valley called “Valley of Cedron;”

Years ago I suggested Nazarite Queen Helena of Abiabene was the Sleeping Beauty Princess, Rosamond. Her sarcophagus lies at rest under the pyramid of the Louvre, the place where Dan Brown’s Fairytale suggests Mary Magdalene, the wife of Jesus is interred. There is not name in the whole internet like that of my grandmother, Mary Magdalene Rosamond, whose granddaughter married a Benton. Jessie Benton and her husband, John Fremont, had Hungarian ex-patriots in their bodyguard, that fought against the Confederated slave masters of the new Roman empire whose false evangelical prophets have taken over Fremont’s party in order to take from the poor, the widow, and the elderly in order to give to the Imperial Billionaires of America.

The Roman swine who pretend to be wolves captured the beuatiful Menorah that Queen Helena gave as a gift to the Jewish people. My story ‘Capturing Beauty’ will bring the Light of God – home! I will overcome the world!

Johanne Wolferose

Judaism in Adiabene survived the death of Izates and Helena. History indicates that the Jewish religion continued to play a part in the kingdom of Adiabene; non-royal Adiabenians converted. “The names of the Adiabenite [sic] Jews Jacob Hadyaba and Zuga (Zuwa) of Hadyab,”33 indicate a non-Hebrew origin and possible conversion to Judaism.

Mindful of the events which in her view were of a positive nature, Helena journeyed with her retinue to Jerusalem and the Great Temple to worship and offer thank-offerings while the throne in Arbela had been safeguarded. Queen Helena offered items of blessing including a special addition to the Kodesh, or Inner Sanctuary of the Great Temple:

The doorway of the Kodesh was 10 cubits wide and 20 cubits high. Over the doorway was a carving of a golden menorah donated by Queen Helena, a convert to Judaism. The morning service could not begin before sunrise. The Temple was surrounded by high walls, and it was not possible to see the rising sun, so priest had to be sent outside to see if it was time for the service to begin. After Queen Helena donated the Menorah, it was no longer necessary to send a priest outside the Temple. As the sun rose in the east it shone against the menorah and the reflected light was cast into the Azarah. The priests then knew that the morning service could begin.18

Kevin Brook cites that the Jewish kings of Adiabene were regularly involved in policy and military affairs. In 61 CE, Monobazus II, the king who Izates meant to succeed him, sent troops to Armenia to try to thwart an invasion of Adiabene. Two years later, he was in attendance at a peace settlement between Parthia and Rome. During the war of Judea against the Roman Empire (66-70 CE), the Adiabenian royal family supported the Judean side.34

According to Paul E. Kahle, there were many Jews in the city of Arbela even after the establishment of bishops and the spread of Christianity in Adiabene.35

Leave a comment