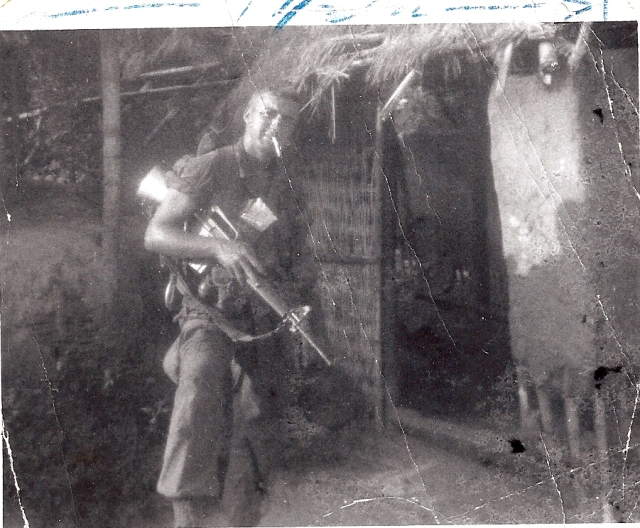

Not too many Baby Boomers, and original hippies, can say their stepfather was a Screaming Eagle. Robert Miles is six months my junior, and fought in Vietnam with the 101st Airborne. Robby met my mother in the Balboa Lounge in Reseda just before he was sent to Vietnam. He told Rosemary if he survives, he will come home and marry her. He was a man of his word. Robby adopted all the Presco children and their children. He took Rosemary’s grandchildren camping every summer.

In Vietnam Robby was amongst the Renegades, a group of soldiers who took no orders, and set out at night to fulfil their quota after it was announced being in Vietnam was about “body count”. No one messed with Robby and his brothers. They returned to camp wearing necklaces of Vietcong ears which they delivered at the entrance of the officers tent. This is what Robby told two of my friends at my wedding reception.

Many folks who claim they are patriots want to be seen as bad-asses – and drunks! Robby only went to a bar to get in a fight. He never lost. He wanted to fight me when we first met. Hence, Robby told me he loves me – all the time! The last time I saw Robby he was in bed with my mother smoking pot.

“Want some?” Robby asked as I made my way to the bathroom.

Peace!

Robby was surrounded by Hippies. He killed many human beings. Robby was a killing machine that swooped out of the sky. He was terrifying. The American Eagle has been compared to the Phoenix Bird. At Hollis’ memorial, I said this to Maria Cortez of HUD-VASH. Robby and Hollis are in my family tree.

“I want to the war in Vietnam – to end!”

Maria looked puzzled. She is around 24 years of age. It had ended for Hollis and I because we declared it over – for us! We made a pledge that we would spend our remaining years living happily outside the great divide that war made in our Democracy, that many Veterans make even wider as radical End Time evangelicals. For these bad-asses, their holy war is over………Surrender!

Samson is the greatest warrior in the Bible. He was a Nazarite. His name is a riddle. In many respects he is the Un-named Soldier. Where he is buried, no one knows.

Samson has been compared to Heracles/Hercules. The Screaming Phoenix Bird is associated with the Phoenicians and Melqart ‘The King of the City’…….the city of Jerusalem. The Romans destroyed Carthage, and hated the Phoenician Sea-Rovers who raided their shipping in the Medirranian. Many Hellenized Jews adopted Heracles and Melqart. John the Baptist and his disciples preached amongst the Greeks, the rivals of Rome. Paul was a roman agent hired to destroy this alliance. The Pope in Rome is modeled after the Pontiff Maximus, the Roman High Priest of Augury. Pontius Pilate was a master augur.

Hiram, the Phoenician, built Solomon’s temple. Did he install the Phoenix within? Is this the angel with no name that Zachariah saw, he given the name and thus was filled with the holy spirit, his lips sealed lest he speak – THE NAME? Was John gifted with THE NAME?

I bid all God’s Warriors to take the Vow of the Nazarite and be one with God. Help crush the rise of alcoholism amongst our nation’s young.

I suspect David’s fighting men were Phoenician warriors who do the Pyrrhic fire dance to this very day. It is from the ashes of this fire – that we are reborn. I believe Jesus entered Jerusalem as Melqart, and the sign nailed above his head read ‘King of the city’. I believe Jesus walked on the water as Melqart, and rose from the dead – like the Phoenix Bird!

It is time for America to be – REBORN!

Arise my fellow Nazarites! Arise!

Jon the Nazarite

Copyright 2013

Upon its arrival in Vietnam in 1965 (1st Brigade, followed by the 2nd and 3rd Brigades in 1968), the division was an airborne unit. In mid-1968 it was reorganized and redesignated as an airmobile division, then in 1974 as an air assault division. Both of these titles reflect the fact that the division went from airplanes as the primary method of delivering troops into combat, to the use of helicopters as the way the division entered battle. Many current members of the 101st are graduates of the U.S. Army Air Assault School and wear the Air Assault Badge. Division headquarters is at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. In recent years, the division has served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The division is one of the most highly decorated units in the U.S. Army and has been featured prominently in military fiction since its first deployment.

Heracles (pron.: /ˈhɛrəkliːz/ HERR-ə-kleez; Greek: Ἡρακλῆς, Hēraklēs, from Hēra, “Hera”, and kleos, “glory”[1]), born Alcaeus[2] (Ἀλκαῖος, Alkaios) or Alcides[3] (Ἀλκείδης, Alkeidēs), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, foster son of Amphitryon[4] and great-grandson (and half-brother) of Perseus. He was the greatest of the Greek heroes, a paragon of masculinity, the ancestor of royal clans who claimed to be Heracleidae (Ἡρακλεῖδαι) and a champion of the Olympian order against chthonic monsters. In Rome and the modern West, he is known as Hercules, with whom the later Roman Emperors, in particular Commodus and Maximian, often identified themselves. The Romans adopted the Greek version of his life and works essentially unchanged, but added anecdotal detail of their own, some of it linking the hero with the geography of the Central Mediterranean. Details of his cult were adapted to Rome as well.

Extraordinary strength, courage, ingenuity, and sexual prowess with both males and females were among his characteristic attributes. Heracles used his wits on several occasions when his strength did not suffice, such as when laboring for the king Augeas of Elis, wrestling the giant Antaeus, or tricking Atlas into taking the sky back onto his shoulders. Together with Hermes he was the patron and protector of gymnasia and palaestrae.[5] His iconographic attributes are the lion skin and the club. These qualities did not prevent him from being regarded as a playful figure who used games to relax from his labors and played a great deal with children.[6] By conquering dangerous archaic forces he is said to have “made the world safe for mankind” and to be its benefactor.[7] Heracles was an extremely passionate and emotional individual, capable of doing both great deeds for his friends (such as wrestling with Thanatos on behalf of Prince Admetus, who had regaled Heracles with his hospitality, or restoring his friend Tyndareus to the throne of Sparta after he was overthrown) and being a terrible enemy who would wreak horrible vengeance on those who crossed him, as Augeas, Neleus and Laomedon all found out to their cost.

In Greek mythology, a phoenix or phenix (Ancient Greek φοίνιξ phóinīx) is a long-lived bird that is cyclically regenerated or reborn. Associated with the sun, a phoenix obtains new life by arising from the ashes of its predecessor. The phoenix was subsequently adopted as a symbol in Early Christianity. The phoenix is referenced in modern popular culture.

In his study of the phoenix, R. van der Broek summarizes, that, in the historical record, the phoenix “could symbolize renewal in general as well as the sun, Time, the Empire, metempsychosis, consecration, resurrection, life in the heavenly Paradise, Christ, Mary, virginity, the exceptional man, and certain aspects of Christian life”.[1]

Early Christianity is the period of Christianity preceding the First Council of Nicaea in 325. It is typically divided into the Apostolic Age and the Ante-Nicene Period (from the Apostolic Age until Nicea).

The first Christians, as described in the first chapters of the Acts of the Apostles, were all Jewish, either by birth, or conversion for which the biblical term proselyte is used,[1] and referred to by historians as the Jewish Christians. The New Testament’s Book of Acts and Epistle to the Galatians record that the first Christian community was centered in Jerusalem and its leaders included Peter, James, and John.[2] Paul of Tarsus, after his conversion to Christianity, claimed the title of “Apostle to the Gentiles”. Paul’s influence on Christian thinking is said to be more significant than any other New Testament writer.[3] By the end of the 1st century, Christianity began to be recognized internally and externally as a separate religion from Rabbinic Judaism which itself was refined and developed further in the centuries after the destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple.

The modern English noun phoenix derives from Middle English fenix (before 1150), itself from Old English fēnix (around 750). Old English fēnix was borrowed from Medieval Latin phenix and, later, from Latin phoenīx, deriving from Greek φοίνιξ phóinīx.[2]

During the Classic period, the name of the bird, φοίνιξ, was variously associated with the color purple, ‘Phoenician’, and the date palm.[3] According to an etymology offered by the 6th and 7th century archbishop Isidore of Seville, the name of the phoenix derived from its purple-red hue, an explanation that has been influential. This association continued into the medieval period, albeit in a different fashion; the bird was considered “the royal bird” and therefore also referred to as “the purple one”.[3]

With the deciphering of the Linear B script in the 20th century, however, the ancestor of Greek φοίνιξ was confirmed in Mycenaean Greek po-ni-ke, itself open to a variety of interpretations.[4]

[edit] Relation to the Egyptian benu

Classical discourse on the subject of the phoenix points to a potential origin of the phoenix in Ancient Egypt. In the 19th century scholastic suspicions appeared to be confirmed by the discovery that Egyptians in Heliopolis had venerated the benu, a solar bird observed in some respects to be similar to the Greek phoenix. However, the Egyptian sources regarding the benu are often problematic and open to a variety of interpretations. Some of these sources may have been influenced by Greek notions of the phoenix.[5]

[edit] Analogues

Scholars have observed analogues to the phoenix in a variety of cultures. These analogues include the Persian anka, the Hindu garuda and Gandaberunda, the Russian firebird, the Persian simorgh, the Turkish kerkes, the Tibetan Me byi karmo, the Chinese fenghuang, and the Japanese ho-oh.[6]

Melqart, properly Phoenician Milk-Qart “King of the City”,[1] less accurately Melkart, Melkarth or Melgart, Akkadian Milqartu, was tutelary god of the Phoenician city of Tyre as Eshmun protected Sidon. Melqart was often titled Ba‘l Ṣūr “Lord of Tyre”, the ancestral king of the royal line. In Greek, by interpretatio graeca he was identified with Heracles and referred to as the Tyrian Herakles.

Melqart was venerated in Phoenician and Punic cultures from Syria to Spain. The first occurrence of the name is in a 9th-century BCE stela inscription found in 1939 north of Aleppo in northern Syria, the “Ben-Hadad” inscription, erected by the son of the king of Arma, “for his lord Melqart, which he vowed to him and he heard his voice”.[2]

“Mozia ephebe” – Melqart (?)

Melqart is likely to have been the particular Ba‘al found in the Tanach,[3] whose worship was prominently introduced to Israel by King Ahab and largely eradicated by King Jehu. In 1 Kings 18.27, it is possible that there is a mocking reference to legendary Heraclean journeys made by the god and to the annual egersis (“awakening”) of the god:

And it came to pass at noon that Elijah mocked them and said, “Cry out loud: for he is a god; either he is lost in thought, or he has wandered away, or he is on a journey, or perhaps he is sleeping and must be awakened.”

The Hellenistic novelist, Heliodorus of Emesa, in his Aethiopica, refers to the dancing of Tyrian sailors in honor of the Tyrian Heracles: “Now they leap spiritedly into the air, now they bend their knees to the ground and revolve on them like persons possessed”.

The historian Herodotus recorded (2.44):

In the wish to get the best information that I could on these matters, I made a voyage to Tyre in Phoenicia, hearing there was a temple of Heracles at that place, very highly venerated. I visited the temple, and found it richly adorned with a number of offerings, among which were two pillars, one of pure gold, the other of smaragdos, shining with great brilliance at night. In a conversation which I held with the priests, I inquired how long their temple had been built, and found by their answer that they, too, differed from the Hellenes. They said that the temple was built at the same time that the city was founded, and that the foundation of the city took place 2,300 years ago. In Tyre I remarked another temple where the same god was worshipped as the Thasian Heracles. So I went on to Thasos, where I found a temple of Heracles which had been built by the Phoenicians who colonised that island when they sailed in search of Europa. Even this was five generations earlier than the time when Heracles, son of Amphitryon, was born in Hellas. These researches show plainly that there is an ancient god Heracles; and my own opinion is that those Hellenes act most wisely who build and maintain two temples of Heracles, in the one of which the Heracles worshipped is known by the name of Olympian, and has sacrifice offered to him as an immortal, while in the other the honours paid are such as are due to a hero.

Josephus records (Antiquities 8.5.3), following Menander the historian, concerning King Hiram I of Tyre (c. 965–935 BCE):

He also went and cut down materials of timber out of the mountain called Lebanon, for the roof of temples; and when he had pulled down the ancient temples, he both built the temple of Heracles and that of `Ashtart; and he was the first to celebrate the awakening (egersis) of Heracles in the month Peritius.[4]

1 Samuel 22:2 – All those who were in distress or in debt or discontented gathered around David, and he became their leader. About four hundred men were with him.

2 Samuel 23:8 – These are the names of David’s mighty men: Josheb-Basshebeth, a Tahchemonite, chief of the captains. He was called Adino the Eznite. He killed eight hundred men in one encounter.

A Pyrrhic victory is a victory with such a devastating cost that it carries the implication that another such victory will ultimately lead to defeat. Someone who wins a Pyrrhic victory has been victorious in some way; however, the heavy toll negates any sense of achievement or profit.

[edit] Etymology

The phrase Pyrrhic victory is named after King Pyrrhus of Epirus, whose army suffered irreplaceable casualties in defeating the Romans at Heraclea in 280 BC and Asculum in 279 BC during the Pyrrhic War. After the latter battle, Plutarch relates in a report by Dionysius:

The armies separated; and, it is said, Pyrrhus replied to one that gave him joy of his victory that one more such victory would utterly undo him. For he had lost a great part of the forces he brought with him, and almost all his particular friends and principal commanders; there were no others there to make recruits, and he found the confederates in Italy backward. On the other hand, as from a fountain continually flowing out of the city, the Roman camp was quickly and plentifully filled up with fresh men, not at all abating in courage for the loss they sustained, but even from their very anger gaining new force and resolution to go on with the war.

—Plutarch, [1]

In both of Pyrrhus’s victories, the Romans suffered greater casualties than Pyrrhus did. However, the Romans had a much larger supply of men from which to draw soldiers, so their casualties did less damage to their war effort than Pyrrhus’s casualties did to his.

The report is often quoted as “Another such victory and I come back to Epirus alone”,[2] or “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined.”[3]

The term is used as an analogy in fields such as business, politics, and sports to describe struggles that end up ruining the victor. Theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, for example, commented on the necessity of coercion in preserving the course of justice by warning, “Moral reason must learn how to make coercion its ally without running the risk of a Pyrrhic victory in which the ally exploits and negates the triumph.”[4] Also, in Beauharnais v. Illinois, a 1952 U.S. Supreme Court decision involving a charge proscribing group libel, Justice Hugo Black alluded to the Pyrrhic War in his dissent: “If minority groups hail this holding as their victory, they might consider the possible relevancy of this ancient remark: ‘Another such victory and I am undone.'”[5]