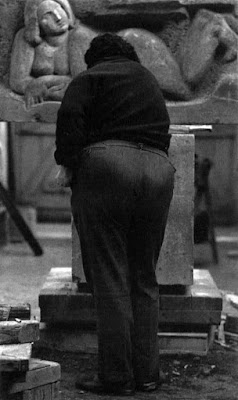

Diego Rivera, Mexico City,1924. Photo by Edward Weston. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Weston Collection.

Knowing of his close friend Diego Rivera’s November-December 1930 exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor and his exciting San Francisco mural commissions, Edward Weston decided come up from Carmel to pay him a surprise visit at his mutual sculptor friend Ralph Stackpole’s Jessop Place studio. Weston also wanted to bask in the concurrent exhibition of his own work at the Vickery, Atkins and Torrey Gallery and socialize with photographer friends Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange and husband Maynard Dixon, and Imogen Cunningham and husband Roi Partridge and others.

Sydney Morris all but destroyed the estate of Brett Weston, and destroyed the estate of Christine Rosamond Benton. My good friend was good friends of the Stackpole family, and went with ne to Christine’s funeral. I talked to Carrol Williams for an hour on the phone.

John Presco

“According to Williams, she was approached by Morris in the fall of ”95 to discuss the purchase of the archive.

“Sidney told me it had been decided that the entire vault was going to be sold because Erica wanted money instead of prints,” says Williams.

“I was told by Sidney that Brett would have wanted me to have the [archive] and that he was prepared to do battle for me with Erica,” adds Williams. “What I got from Sidney was he didn”t want the liability and responsibility and management headaches of selling the archive individually.”

According to Morris, the estate had given consideration to managing Weston”s archive itself, but decided that such a time-consuming and complicated endeavor was not worth the potential financial risks and uncertainty.

“We had considered trying to manage the estate and running it as a business, but in view of what we had to deal with, in our opinion to run it as a business entity would have been long and arduous and maybe not successful,” says Morris. “Erica”s lawyers and my lawyers felt it would be in the best interests of the estate to dispose of substantially all of the collection.”

Southern California Architectural History

A Blog for fans of the cultural, architectural and design history of Southern California and related published material authored by John Crosse: jocresse979@gmail.com

Sunday, March 12, 2017

Edward Weston, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, December 1930

Diego Rivera, Mexico City,1924. Photo by Edward Weston. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Weston Collection.

Knowing of his close friend Diego Rivera’s November-December 1930 exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor and his exciting San Francisco mural commissions, Edward Weston decided come up from Carmel to pay him a surprise visit at his mutual sculptor friend Ralph Stackpole’s Jessop Place studio. Weston also wanted to bask in the concurrent exhibition of his own work at the Vickery, Atkins and Torrey Gallery and socialize with photographer friends Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange and husband Maynard Dixon, and Imogen Cunningham and husband Roi Partridge and others.

Edward Weston and Johan Hagemeyer, Gump’s, Feb., 9 to Feb. 21, 1925. Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, Edward Weston Collection.

During a six month interlude in San Francisco during his 1923-26 Mexican sojourn, Weston was one of the first to introduce Rivera and friends to the Bay Area. Through his close photogropher friend Johan Hagemeyer Weston excitedly exhibited his early Mexican work, including the above photo of Rivera, at a two-man show at Gump’s Department Store (see above).

Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Timothy Pflueger and Ralph Stackpole, November 10, 1930. Photographer unknown. Courtesy San Franciso Public Library Historical Photograph Collection.

Exhibition Catalogue, Diego Rivera, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, November 15 to December 25, 1930. Introduction by Katherine Field Caldwell. From author’s collection.

Frontispiece portrait of Diego Rivera, Mexico City, ca. 1923-4 by Edward Weston. (Ibid).

Diego and Frida, Ralph Stackpole’s Studio, 27 Jessop Place, San Francisco, December, 1930. Photo by Edward Weston. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Weston Collection.

Weston fondly wrote of the visit,

“I met Diego! I stood behind a stone block, stepped out as he lumbered downstairs into Ralph [Stackpole]’s courtyard on Jessop Place, – and he took me clear off my feet in an embrace. I photographed Diego again, his new wife – Frieda – too: she is in sharp contrast to Lupe, petite, – a little doll alongside Diego, but a doll in size only, for she is strong and quite beautiful, shows very little of her father’s German blood. Dressed in native costume even to huaraches, she causes much excitement on the streets of San Francisco. People stop in their tracks to look in wonder. We ate at a little Italian restaurant [Coppa’s] where many of the artists gather, recalled old days in Mexico, with promises of meeting soon again in Carmel. Pfleuger – architect – was another contact worthwhile. He sat to me – on the roof of Ralph’s.” (The Daybooks of Edward Weston, Volume II, California, pp. 198-9. For much more on Coppa’s and fellow Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco’s happy times there see my “Orozco in San Francisco, 1917-1919“).

Frida Kahlo, Ralph Stackpole’s Studio, 27 Jessop Place, San Francisco, December, 1930. Photo by Edward Weston. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Weston Collection.

Diego Rivera, Ralph Stackpole’s Studio, 27 Jessop Place, San Francisco, December, 1930. Photo by Edward Weston. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Weston Collection.

Lady Hastings, San Francisco, ca. 1930. Photo by Edward Weston from The San Franciscan, April 1931, p. 21.

The wife of Lord Hastings, one of Rivera’s mural assistants, also sat for a portrait while Weston was in town. It was published in the April 1931 issue of The San Franciscan with the caption,

“Lady Hastings who is being widely entertained during her sojourn in San Francisco, while her husband, Lord Hastings, assists Diego Rivera with fresco panels in the Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts.”

Storer House, 8161 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood, Frank Lloyd Wright, architect, 1924.

Weston made prints of his San Francisco reconnection with Rivera before heading south for the holidays to visit the family. Brett, who had recently established his first independent studio in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Storer House (see above) through the largess of Pauline Schindler, picked up his father in Carmel and drove him back to Los Angeles. (For more detail see my “Brett Weston’s Smokestacks and Pylons“).

“Toward the Big Sur” by Edward Weston, The Carmelite, May 2, 1929. Courtesy Harrison Memorial Library, Carmel.

While in Southern California Weston hooked up with close friends Johan Hagemeyer, Merle Armitage and Ramiel McGehee and visited Pauline at the Storer House. She had herself recently returned from a two year sojourn in Carmel where she edited and published the local progressive weekly newspaper, The Carmelite in which she frequently featured the work of Weston (see above for example). He shared with her his prints of Rivera and other recent work prompting her to recommend he send them off to various suggested publications. (For much more on Pauline’s marketing efforts on behalf of the artists and architects in her wide circle see my “Pauline Gibling Schindler: Vagabond Agent for Modernism“).

Diego Rivera, Ralph Stackpole’s Studio, 27 Jessop Place, San Francisco, December, 1930. Photo by Edward Weston. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Weston Collection.

Of the Rivera prints she recommended,

“i think also that the Rivera pictures should be used now while the san francisco work is hot. why not send it to “creative art?” or “the international studio?” or whatever publication you consider superlative in that line. or send the glossy to me, and i will send it to where you suggest, with a brief accompanying article. how about sending the rivera beside mop and garbage can (see above) to “the new masses?” please let me know exact details as much as possible of the s. f. paintings of rivera for my articles.” (Pauline Schindler to Edward Weston, February 13, 1931. Center for Creative Photography, Weston Papers).

Pauline would have been dying to meet Rivera knowing full well of his politics from Weston and former Schindler House tenant and Blue Four art dealer Galka Scheyer and the news media. She would meet Rivera through Scheyer and mutual friend Marjorie Eaton on a trip to the Bay Area two weeks later. (Ibid).

Galka Scheyer had been staying with Pauline and Brett and perhaps crossed paths with mutual friend Weston when she visited Rivera in San Francisco to solicit his co-sponsorship for her upcoming Blue Four exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in April. (For much more on the Scheyer-Rivera connection see my “Schindler-Scheyer-Eaton-Ain: A Case Study in Adobe”).

(Author’s note: Brett Weston had photographed Mexican muralist amigo Jose Clemente Orozco in the spring of 1930 while he was creating his Prometheus mural at Pomona College. His father photographed him in Carmel during a July visit with his dealer Alma Reed while they were in San Francisco scouting for mural walls and preparing for his upcoming exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). (For more details on Orozco’s 1930 California visit see my “Brett Weston’s Smokestacks and Pylons,” “Richard Neutra and the California Art Club” and “Orozco in San Francisco, 1917-1919“).

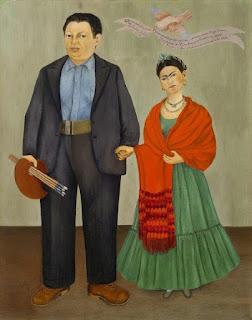

Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931 by Frieda Kahlo. Courtesy FridaKahlo.org.

(Author’s note 2: In November of 1931 a portrait of Frieda and Diego Rivera painted by “Senora Frieda Rivera” of Mexico City during their 1930-31 stay in San Francisco (see above) was selected for the juried Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists at the Legion of Honor. This was the first public showing of Frida Kahlo’s work). (“Art and Artists,” Oakland Tribune, November 8, 1931, p. 22). (For much more on this see my “Schindler-Scheyer-Eaton-Ain: A Case Study in Adobe“).

Lovell Beach House, Newport Beach, R. M. Schindler, architect, 1926. Photo by Edward Weston, August 2, 1927. Courtesy UC-Santa Barbara Architecture and Design Collections, Schindler Papers.

The material in this and linked posts will be part of a larger project, “The Schindlers and the Westons: An Avant-Garde Friendship” (see above).

Sydney Morris and Brett Weston

Posted on March 20, 2021 by Royal Rosamond Press

Sydney Morris works for, or is a partner of Robert Buck, who put together the Buck Foundation employing his legal expertise. Morris destroys the estate of Brett Weston and Christine Rosamond Benton, two of Carmel’s most creative citizens. Jack London and George Serling founded this famous Bohemian Mecca. Ben Maddow wrote Edward Weston’s biography.

Here is a Buck Baby going after Gavin Newsom thinking they are saving Californians from becoming alcoholics or – whatever! The whole board ignores me – and my late sister.

John Presco

One of modern photography’s greatest pioneers, Edward Weston awakened his viewers to the sensuous qualities of organic forms. In this biography Ben Maddow draws heavily on Weston’s uncut journals and letters and on the reminiscences and written accounts of his closest friends and family to reveal the man behind the opaque formalism of the photographs.

Lawsuit Against Buck, Chazen, Pierrot, and Comstock | Rosamond Press

Governor Newsom: Don’t Let Your Wine Interests Trump Your Ethics – Alcohol Justice

So back to the pun in our title: Gov. Newsom, will your wine interests Trump your ethics? President Trump is under suspicion of violating the emoluments clause of the Constitution. Is the President financially gaining from the Trump Hotel on the Capital Mall by sucking in foreign visitor monies? While California’s constitution does not have an emoluments clause, the same conflicts of interest arise. If the 4 a.m. Bar Bill lands on Governor Newsom’s desk, he could gain financially from signing the bill, through wine sales and through the PlumpJack Squaw Valley Inn. Alcohol Justice must directly ask: Governor-elect Gavin Newsom – could you please completely divest from the wine industry and invest in public health? And please do not support any attempts to further gut alcohol regulations which have been deteriorating for decades in California while the body and injury counts rise.

READ MORE about the ongoing alcohol catastrophe in California.

Members of Gavin Newsom’s wine, restaurant, bar, resort and real estate partnerships since 1991:

Kevin & Bronwyn Brunner, John Burton, Casey and Michelle Cadwell, Bob and Barbara Callan, Frank Caufield, Donna Chazen, Lawrence Chazen, Joe & Victoria Cotchett, Michael & Hilary Decesare, Philip DeLimur, Don Dianda, Gretchen Dianda, Edward Everett, Richard Freemon, James Fuller, Stanlee Gatti, Robert Gerry, Andrew Getty, Ann Getty, Anna Getty, Chris Getty, Gordon Getty, Mark Getty, Peter Getty, Ronald Getty, Tara Getty, William “Billy” Getty, Robert Goldberg, Florianne Gordon, Stu Gordon, Gordon Goletto, David Goodman, Arthur Groza, Richard & Martha Guggenhime, Tony and Anthony Guilfoyle, Shelly Guyer, James & Shea Halligan, Bob & Jill Hamer, Erin Howard, Thomas Huntington, Isolep Enterprises (Paul and Nancy Pelosi family personal investment company), Peter Jacobi, Gaye Jenkins, Jeffrey Kanbar, Chad Kawai, David Lamonde, John Larson, Rob Lavoie, Leavitt/Weaver interior designers, Marc Leland, Maryon Davies Lewis, Anne McCutcheon, Chris McCutcheon, Ross McGowan, Rich McNally, Robert & Carole McNeil, Paul Mohun, Robert Mohun, Jeff Morin, Sara Moughan, Terry Moughan, Brian Mueth, Bob Naify, Marshall Naify, John Nees, Barbara Newsom, Brennan Newsom, Catherine & David Newsom, Gavin Newsom, Patrick Newsom,

Tessa Newsom, William Newsom, John O’Hara, Jack Owsley, Pacific Design, Matt Pelosi, Robynne Piggott, James Samuel Powers, Elizabeth Rice, Jeremy Scherer, Paul Scherer, Gary Schnitzer, Steve & Theresa Selover, Steve Siino, Trevor Traina, Chris Vietor, Francesca Vietor, Kenneth Weeman, Nicki West, Justin & Aridne Williams, Kevin Williams, Thomas & Kiyoko Woodhouse

“By September 2000, however, plans were underway for a biography of Decedent, which Petitioner hoped might create interest in her work. The book was published in 2002. Although the book did not spur the hoped-for interest in Decedent’s life and work, efforts continued to market the concept of a screenplay based upon Decedent’s life. Petitioner hoping that this might be brought to fruition, elected to keep the estate open. However, it is the Petitioner’s belief the likelihood of an increased interest in Decedents work is negligible, and the time has come to close the estate.”

“Pierrot later bought the business from the estate, royalties

from which go to Rosamond’s daughters, Drew now 11, and Shannon, 28.

Pierrot has a determined vision of where she wants the business to

go. A poster of Rosamond’s creation “Dunkin the Frog” will be

distributed to children in hospitals. T-shirts and tote bags will

also be produced featuring the whimsical character, Pierrot says. All

manner of upscale merchandising is contemplated using the images from

Rosamond’s paintings…bed linins, throw pillows and other elegant

household items.”

“As suggested by a review of the court documents and interviews with many of the principals in the court case, the dispute over Weston”s estate has been a grotesque, acrimonious soap opera, replete with insinuations and outright charges of deception, theft, financial manipulation, malfeasance and mismanagement.”

http://www.amazon.com/Rosamond-Complete-Catalogue-Raisonne-1947-1994/dp/0615359892

“Many of these pictures have not been in public viewing but rather have been copied from private owners. There are between 180 and 190 pictures at least to enjoy.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Frog_Prince

http://www.oldsf.org/#ll:37.779049|-122.428520&m:37.77059|-122.39590|14

I don”t think of it in terms of money. I do it just for the love and excitement.”

-Brett Weston

It was 40 years ago on New Year”s Day that photographer Edward Weston died at his home on Wildcat Hill in the Carmel Highlands. Despite decades of struggle, during which he never earned more than a few hundred dollars for images that are now regarded as masterworks of 20th century photography, Weston came to be recognized as one of modern photography”s true geniuses.

In the five years since Brett Weston, Edward Weston”s second son, died at the age of 81 at his home on the Kona coast in Hawaii, he too has come to be regarded as a photographic genius in his own right, one whose singular vision and bold abstract landscapes anticipated and paralleled many of the major trends of 20th century art.

Unlike his father, however, Brett Weston achieved substantial wealth during his lifetime. Abetted by the art boom of the late ”70s and ”80s, and the growing recognition of photography as a legitimate art form, many of Weston”s better-known images sold for upwards of $5,000 apiece. In addition, Weston earned hundreds of thousands of dollars from numerous book contracts and the sale of reproductions of his images.

At the time of his passing, Weston left behind an estate valued at well over $2 million and an astonishing archive of some 30,000 photographs, spanning his entire, seven-decade career. Many of these images, all printed by Weston himself, have never been exhibited or reproduced. In order to assure both the value and integrity of his archive, Weston destroyed nearly 7,000 of his negatives-a bold act that defied art-world conventions and that continues to cause much debate and consternation among art historians.

As art historians seek to evaluate Weston”s legacy and influence on 20th-century art and photography, it is Weston”s archive that will form the basis for much of that assessment. In terms of photographic history, the archive is priceless. But in the real world, where everything has a price, the archive and Weston”s legacy have become bones of contention.

For the past year and a half, the county courthouse in Monterey has been the scene of a contentious and oftentimes bitter legal dispute over Brett Weston”s estate and the disposition of his photographic archive-one that could have far-reaching implications for the legacy of Weston”s artistic achievement.

At the center of the dispute is Weston”s long-time agent and friend, Carol Williams, owner and director of the Photography West Gallery in Carmel, and Carmel attorney Sidney Morris, executor for the Weston estate.

The point of contention between Williams and Morris has been the sale of Weston”s entire photographic archive to an Oklahoma banker and art collector named Christian Keesee, as well as the status of ongoing print sales, and a previous publishing contract between Weston and the Photography West Gallery.

At issue is whether the sale to Keesee, which was finalized and approved by the court last summer despite efforts by Williams to overturn the sale, violated Weston”s expressed interests for his archive, and whether the sale will have a negative impact on the value of Weston”s work and its assessment by art historians.

As suggested by a review of the court documents and interviews with many of the principals in the court case, the dispute over Weston”s estate has been a grotesque, acrimonious soap opera, replete with insinuations and outright charges of deception, theft, financial manipulation, malfeasance and mismanagement.

The path to understanding the convoluted and confusing path that led to the sale of Weston”s archive to Keesee, is littered by a host of self-serving half-truths, dissembling and dissimulation by former friends, lovers, acquaintances and art-world associates of Weston that make the parties” motives and the truth difficult to ascertain.

At the center of this legal miasma resides Brett Weston himself, a man who emerges from past interviews and conversations with friends and associates as an enigmatic and incongruous personality, a man whose intentions regarding his archive were never made clear and whose single-minded pursuit of his art often came at the expense of personal and professional relationships.

“I have spoken all my life through the camera. Photographs are the statements and legacy that I have left.”

-Brett Weston

In looking back at Brett Weston”s life and career as an artist, one is struck by the degree to which his art is inextricably linked to his relationships with women. Married and divorced four times, Weston engaged in countless personal relationships with women, many of whom assisted Weston professionally.

From March of 1959 to August of 1992, less than five months before his death, Weston left as many as 10 wills with 16 codicils, with many of the amendations representing changes in executors and beneficiaries.

According to Morris and former estate co-executor and Weston friend Bob Byers, there were 29 versions of estate plans for Weston during his lifetime, “the common theme being gifts to lady friends and family members and to ultimately take care of [Weston”s daughter and sole heir] Erica,” according to Morris.

For Josephus Daniels, a respected Carmel photography dealer who represents some of Weston”s work, there is knowing amusement in the complicated and messy estate Weston left behind.

“Brett was a very complex fellow yet simplistic in other ways,” says Daniels. “Brett”s world was very rigid and internalized and he had very specific ideas about the world of art and his relation to it.

“The whole family was a dysfunctional family, and Brett had difficult times with relationships,” adds Daniels. “I don”t know if Brett ever lost control [of his archive], but I don”t know if he ever had control of it either.”

Over the years, Weston also vacillated over the disposition of his negatives, with earlier wills stipulating the destruction of any remaining negatives and later wills approving the donation of some negatives to educational institutions. Prior to his death, Weston did donate approximately 12 negatives to the Center For Creative Photography in Tucson, Ariz., and gave another dozen to his brother, the noted photographer Cole Weston. In both cases, all the negatives were sufficiently damaged to prevent future printing. What negatives have survived include several hundred images taken in Hawaii during the latter part of Weston”s life. None of these images are believed to have been printed, and according to Morris, these negatives have been donated to the Center as part of the sale to Keesee with instructions that they may never be printed.

In his final codicil just months before his passing, Weston made one significant change in his will that bears significantly on the sale of his archive to Keesee. After writing numerous wills naming the San Francisco Museum of Modern art as the “remainder trust” beneficiary of his archive, Weston switched to the Center, reportedly through the importuning of Diane Nielsen, a photographer and personal friend who works for the Center, and who was named as a beneficiary of 25 prints in Weston”s will.

That change came as a surprise to some Weston associates who say Weston had a longstanding enmity against the Center over its refusal to purchase his works as it had done for other photographers of equal stature, and its insistence that Weston donate images to the Center instead.

Despite all the changes in Weston”s will over the years, the one constant and concern, all parties agree, was to see to it that his daughter Erica would be provided for.

Given the complex and complicated nature of Weston”s personal life and the uncertainties surrounding his wills, it is not too surprising that his archive should have been in similar disarray.

“In the four years the vault was in my possession, I could not deliver a single requested photograph because I didn”t have it or would have had to break up a portfolio,” says Morris, who says the archive, which was “poorly catalogued,” was twice appraised at around $1.2 million, not including the potential value from publishing and reproduction rights.

As Brett Weston”s primary dealer for the last 13 years of his life, Carol Williams seemed an obvious choice to purchase Weston”s archive. Besides earning Weston hundreds of thousands of dollars over the years, Williams helped broaden the appreciation of Weston”s work through her gallery”s publication of three beautifully produced and highly regarded monographs of Weston images. Those books were published prior to Weston”s death as part of a five-book deal, the remainder of which is currently being disputed by Morris on behalf of the Weston estate.

According to Williams, her personal and professional relationship with Weston gave her unique insight into the man and his art, and Williams remains a passionate and devoted believer in Weston and his artistic legacy. It was Williams” dream, and according to Williams, Brett”s desire as well, to see his work remain in Carmel. Williams says she intended, had she purchased the archive, to sell some of the collection in order to finance construction of a photography center or museum that would pay tribute to the entire Weston family, a family indelibly linked to the Carmel area.

According to Williams, she was approached by Morris in the fall of ”95 to discuss the purchase of the archive.

“Sidney told me it had been decided that the entire vault was going to be sold because Erica wanted money instead of prints,” says Williams.

“I was told by Sidney that Brett would have wanted me to have the [archive] and that he was prepared to do battle for me with Erica,” adds Williams. “What I got from Sidney was he didn”t want the liability and responsibility and management headaches of selling the archive individually.”

According to Morris, the estate had given consideration to managing Weston”s archive itself, but decided that such a time-consuming and complicated endeavor was not worth the potential financial risks and uncertainty.

“We had considered trying to manage the estate and running it as a business, but in view of what we had to deal with, in our opinion to run it as a business entity would have been long and arduous and maybe not successful,” says Morris. “Erica”s lawyers and my lawyers felt it would be in the best interests of the estate to dispose of substantially all of the collection.”

Prior to discussions with Williams, Morris approached the Center For Creative Photography as a possible buyer. As a research and educational institution housing more than 60,000 photographs, archives books and documents of such noted photographers as Edward Weston, Ansel Adams and Wynn Bullock, the Center seemed a likely choice.

“As Brett”s executor, I hoped I could find some way to create a photographic legacy with the Center after it seemed unlikely the trust could market its entire collection during Erica”s lifetime,” says Morris.

According to Morris, the Center declined to purchase the archive because of its unwillingness to take on the necessary financial obligations such a purchase would entail in terms of providing for Erica Weston and the estate.

“We did pursue in some detail letting the Center have it, but they didn”t want to be responsible for generating income [for Erica and the estate],” explains Morris.

Although the Center declined to purchase Weston”s archive, they were particularly interested in purchasing what is known as the 50th Anniversary Portfolio, a collection of 125 prints of Weston”s finest work spanning his entire career and assembled by noted photo-historians Beaumont and Nancy Newhall for an exhibit in Santa Fe, NM. in the 1970s.

Morris confirms that the Center did want to buy the 50th Anniversary Portfolio, worth an estimated $300,000, but the price that was offered was below market value and “prejudicial to the interest of the income beneficiary.”

As discussions between Morris and Williams proceeded, and a figure of $1.5 million was proposed for purchase of the estate, Williams says she thought the deal would be completed, pending the approval of the sale by Erica and the Center, which Williams says Morris sought as a “”courtesy”” to the Center. But such approvals, says Morris, were not forthcoming.

The response to the proposed sale to Williams, says Morris, was “strictly negative from Erica, and the Center was concerned about Carol personally and her business practices. They thought there would be a sale to another museum and they weren”t enamored with the idea,” says Morris, who insists that no deal was ever finalized between the estate and Williams.

According to Williams, however, “the Center”s attorney told me they never objected to my offer.” Williams adds that Erica told her that her [Erica”s] objections were based on incomplete information regarding the terms of a possible sale to Williams.

After repeated questioning, Morris conceded that the Center had no legal standing to object to the sale. Furthermore, the derogatory allusion to Williams” “business practices” begs the question why Morris would approach Williams in the first place if her business practices were in doubt, and why Weston himself placed such implicit trust in Williams over the years.

Williams says it was only after she was told by Morris that the Center was going to purchase the archive for a larger sum, only to later find out it was sold to Keesee under terms and conditions she felt Brett would have objected to, did she eventually sue to block the sale in May of ”97.

“I was told by Sidney I had it and in January [1997] he said the vault went to the Center for more money than I offered and that Erica was thrilled,” says Williams. “I thought it all went to the Center but it had to been sold to Keesee.”

Williams” suit was eventually denied by Judge William Curtis citing Williams” lack of standing. Curtis later sanctioned Williams $10,000 after she pursued the suit further.

Because the interpretation and recollection of the events surrounding the sale of Weston”s archive varies from person to person, it is difficult to ascertain what assurances, guarantees and/or promises were made to and by all the parties involved in the eventual sale of Weston”s archive to Keesee.

The most likely explanation may have to do with the financial liabilities and benefits of the archive to the estate, the powerful influence of the Center, which benefited substantially from the sale of the archive to Keesee, and the role of Erica”s attorney and advisor Jim Rust, a St. Louis attorney who ended up brokering the deal between the estate and Keesee.

(Both Erica Weston and Jim Rust, per Erica”s instructions, declined to be interviewed for this story. Terence Pitts, who serves as director for the Center For Creative Photography also declined to be interviewed despite the prominent role the Center played in the disposition of Weston”s archive. According to Pitts, there was nothing controversial about the sale of Weston”s archive.)

The sale to Keesee, with the help of his agent Jon Burris, who now serves as curator of the Brett Weston Archive, was completed in November, 1996 following final negotiations in Oklahoma City.

According to court documents, Keesee purchased the archive for the $1.5 million asking price, but only put $200,000 down, agreeing to pay off the additional $1.3 million balance in interest and principal in five years.

In turn, the estate paid a 10 percent commission to Burris and agreed to take out a $300,000 loan from Keesee”s bank. According to Morris, the deal was structured in such a way as to reduce the estate”s overall tax burden, with the bank loan allowing the estate to pay off some of its debts. By deferring payment in full, says Morris, Keesee was able to keep more cash on hand to help finance planned exhibitions and publications of Weston”s work.

In addition to the archive, Morris sold all reproduction rights to Keesee in an exclusive licensing agreement, giving Keesee the right to reproduce and publish Weston”s work for 25 years in exchange for 7 percent of the gross sales to the estate. It has been suggested by sources that those rights could be worth upwards of an additional $1 million.

One of Keesee”s first moves has been to license 1,500 of Weston”s images to Bill Gates” Corbis Corp. of Bellevue, Wash., for electronic reproduction. Keesee retains final approval for any uses by Corbis, which has a similar agreement with the Ansel Adams Trust. According to Morris, the estate has relinquished all control over how Weston”s images can be used or marketed.

As for the Center, it received the 50th Anniversary Portfolio from the estate, along with a donation from Keesee of somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 prints not included in the sale, as well as several hundred negatives of Weston”s later Hawaii work. All of the items donated to the Center will provide tax benefits to Keesee and the estate. According to Morris, title to the Portfolio has yet to be transferred from the estate to the Center.

As far as Morris is concerned, the terms of the sale of the Weston archive represents the best outcome for both Weston”s estate, and for the legacy of Weston”s artistic achievement. Any supposed controversy over the sale, says Morris, is strictly in the mind of Williams, and that Brett never explicitly stated how he wanted his archive disposed of.

“I honestly feel the results achieved over the past four years are as good as could have been achieved for this estate,” says Morris. “We”ve done all we can do and I feel good about it. It has not been easy, but it”s my nature to know what I”m doing is right and doing the best job to get the estate closed.

“In my opinion the Center will have the definitive collection of Brett”s work and as far as everyone else is concerned they couldn”t be happier,” says Morris.

As a coda to the events surrounding the legal fight over the sale of Weston”s archive to Keesee, Williams herself was sued this past October by Morris on behalf of the estate over breach of contract for the remaining two books on Weston”s work, and for the return of 600 Weston photographs intended for those publications. She is also being sued for money Morris says is due the estate as a result of ongoing sales of Weston”s work by Williams at the Photography West Gallery.

Williams says she hadn”t gone forward on the other books because Morris told her the estate didn”t want any additional tax liabilities from any additional sales or promotions.

Morris denies Williams assertions, and says only that negotiations between the estate and Williams are ongoing and may be resolved in January.

“My feeling is she breached her contract for the other two books, and the estate issues have nothing to do with her failure to do the last two books,” says Morris.

“I love appreciation and an audience, we all do, but I don”t photograph for anybody but myself. In general mass audiences are tasteless, and I”d rather have an audience of say a thousand people who really love and understand and appreciate my work than 10 million. ”

-Brett Weston

As loathe as Weston may have been for a large, and largely uninformed audience, it appears as though his reputation will be greatly enlarged in the coming years. In the aftermath of the sale of the Weston archive to Keesee, two questions remain-whether this area lost an invaluable local treasure, and how Brett Weston and his tremendous artistic achievement will be assessed by art historians and the public at large.

Despite questions raised by Williams and Weston”s brother Cole over whether Brett would have approved a sale that included several hundred negatives and the licensing of the electronic publishing rights, based on steps taken so far, Keesee and Burris have shown great savvy and seem serious and forthright in their desire to build on Weston”s legacy in a positive way.

To date, Burris has mounted two shows of Weston”s work-one at the International Center of Photography in New York City of 76 images of New York cityscapes, and a 60-print retrospective in Guadalajara, Mexico- and is in the process of lining up exhibitions in galleries and museums in several European countries over the coming years. Negotiations have also begun, says Burris, with three major American publishers and one foreign publisher for a series of six books over the next five years that Burris says that will “totally reinterpret Brett”s career.”

“Our intention is to bring attention to the fact that not a lot of Brett”s work nor a broad enough range has been reproduced or exhibited,” says Burris, who has been an art dealer/curator for the past 25 years. “Looking at his immense archive that parallels the history of photography, it is amazing in scope and amazing from the standpoint of what was not shown and exhibited. We obviously feel there is great potential with the material and in terms of marketing we intend to bring Brett Weston”s name to greater prominence.”

As far as concerns that the sale to Keesee represents the loss of a valuable local treasure, Burris insists Weston”s value and representation goes beyond such parochial concerns.

“Brett was one of the great American landscape artists and it is unfair to relegate him just to the California school,” says Burris. “If you took a handful of the top six American photographers he is certainly one of them. The fact that any one artist could physically create an archive this wide-ranging is amazing in and of itself.

“Anything projected about what Brett may or may not have wanted is not clearly defined,” adds Burris. “I think, as with many artists, one of things that”s been said is there is some implication Brett might not have wanted his work to leave California and the idea of plans for a museum, but in all of our research we can find nothing to indicate this and I don”t think any of that is true. Had he wanted that specifically, he had people around him who could have helped him set that up but he didn”t do that. As with any artist whose work is on this level it belongs to the history of American photography regardless of where it is handled, as long as it is handled properly.”

As far as Williams is concerned, her feelings are decidedly mixed regarding the sale of Weston”s archive and tied deeply to her personal feeling for Brett as an artist and friend.

“I feel as far as Brett”s legacy is concerned the local area lost a tremendous archive, one of the most important artistic archives that exists in the history of photography ever created,” says Williams, “but I don”t think [the sale to Keesee] was the worst thing that could have happened.

“My concerns for Brett”s work is it”s never been organized or assembled. No scholars or public institutions have had an opportunity for study,” adds Williams. “My overwhelming response is sorrow about the irony of it. It seems so sad it was turned into this big commercial investment. Brett was a visual genius and had as sophisticated an eye as perhaps the most sophisticated 20th-century painters and abstractionists. That is his legacy.

“There needs to be a reevaluation of Brett”s artistic contribution, a chronological scholarly study of his work properly dated with comparative studies done to see who was influencing whom. That was the opportunity presented by the archive-scholarly research-and hopefully it won”t be lost.” cw

Am I Stackpole’s Historian?

Posted on June 4, 2019 by Royal Rosamond Press

Before the death of my late friend, Michael Harkins, I asked him if anyone was taking care of the Stackpole family legacy. He said Peter’s daughter was on it. I am not sure if she is doing enough. I am going to include a chapter in my book.

If I find time I am going to do a painting of Ralph, Frieda, and Rivera from the photograph above. They are in a classic pose. Their raised legs create a religious theme often used by the masters. This pyramid pose is perfectly off-center which balances the differences in weight of the two men, and the leaning towards Rivera, that does not exclude Ralph. Someone knows their art. Who took this photo. This is pure San Francisco. This is a real revolution – with amazing results!

Wow! I just noticed Frieda was a friend of Ed Weston who photographed this famous woman artist. Michael was a good friend of Ralph, Peter, and Peter Stackpole Jr. We went to Peter’s destroyed home after the Oakland fire. Much work was destroyed. Michael helped me investigate the death of Christine Rosamond Benton. He was a good friend of the poet Michael McClure, and Jim Morrison. Stone wanted Michael’s story for his movie. He declined.

When Kahlo and Rivera moved to San Francisco in 1930, Kahlo was introduced to American artists such as Edward Weston, Ralph Stackpole, Timothy Pflueger, and Nickolas Muray.[19] The six months spent in San Francisco were a productive period for Kahlo,[20] who further developed the folk art style she had adopted in Cuernavaca.[21] In addition to painting portraits of several new acquaintances,[22] she made Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931), a double portrait based on their wedding photograph,[23] and The Portrait of Luther Burbank (1931), which depicted the eponymous horticulturist as a hybrid between a human and a plant.[24] Although she still publicly presented herself as simply Rivera’s spouse rather than as an artist,[25] she participated for the first time in an exhibition, when Frieda and Diego Rivera was included in the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists in the Palace of the Legion of Honor.[26][27]

The Creative Stackpoles

Posted on December 7, 2011by Royal Rosamond Press

Ralph Stackpole was a friend of George Sterling and stayed with him and the artists and poets that gathered at Lake Temescal in Oakland. Ralph befriended Diego and Freda Rivera the famous muralist and artist. Ralph helped design the Paramount theatre and a giant statue for Golden Gate Exposition, a goddess named Pacifica.

Peter Stackpole was a staff photographer for LIFE magazine and spent much time in Hollywood shooting the stars, among them, Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor. Peter stayed on Errol Flynn’s boat and was privy to his exploits. My grandmother, Mary Magdalene Rosamond, chased Errol from her home at dawn when he and a friend came serenading.

Jon Presco

Ralph Ward Stackpole (May 1, 1885 – December 13, 1973) was an American sculptor, painter, muralist, etcher and art educator, San Francisco’s leading artist during the 1920s and 1930s. Stackpole was involved in the art and causes of social realism, especially during the Great Depression, when he was part of the Federal Art Project for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Stackpole was responsible for recommending that architect Timothy L. Pflueger bring Mexican muralist Diego Rivera to San Francisco to work on the San Francisco Stock Exchange and its attached office tower in 1930–31.[2] His son Peter Stackpole became a well-known photojournalist.

Throughout the 1930s, Stackpole worked frequently with architect Timothy Pflueger on various commissions. Beginning in 1929 when the two men first met, Stackpole was given responsibility for selecting the artists who worked to execute and augment Pflueger’s basic design scheme for the San Francisco Stock Exchange and its associated Tower, especially the Luncheon Club occupying the top floors of the Tower.[17] Stackpole said later of the experience, “the artists were in from the first. They were called in conference and assumed responsibility and personal pride in the building.”[18] At the Sansome Street tower entrance, Stackpole worked on a scaffolding with a crew of assistants to direct carve heroic figures in stone.[19] After the building was completed, Stackpole was finally successful in winning a commission for Rivera; Pflueger became convinced that Rivera would be the perfect muralist for decorating the staircase wall and ceiling of the Stock Exchange Club. This was a controversial selection considering Rivera’s leftist political beliefs in contradiction to the Stock Exchange’s capitalist foundation.[20] Into the mural, Rivera painted a figure of Stackpole’s son Peter holding a model airplane.

During his stay, Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo lived and worked at the studio, becoming in the process lifelong friends with Stackpole and Ginette. They met tennis champion Helen Wills Moody, an avid painter-hobbyist, who soon agreed to model for Rivera at the studio.[21] Neighbor Dixon saw the attention, and the American money being given to Rivera, and with etcher Frank Van Sloun organized a short-lived protest against the Communist artist. However, both Dixon and Van Sloun quickly realized that the San Francisco art world “oligarchy” who were obviously smitten with Rivera, including Stackpole’s well-connected patrons, were the same group that they themselves would need to support their own art aspirations.[10]

For much of 1931, Stackpole partnered with other artists to decorate Pflueger’s Paramount Theatre in Oakland; an Art Deco masterpiece. A bas-relief scene of horses, waves and a central winged figure was emplaced over the stage’s proscenium arch, finished in gold-toned metal leaf—the work jointly designed by Stackpole and Robert Boardman Howard.[22] The design worked into Pflueger’s metal grille ceiling grid likely came unattributed from Stackpole’s sketches. Pflueger was an able project leader; Stackpole later described his involvement: “He was the boss alright, as an architect should be … He would call the plays just as a symphony conductor does … There wasn’t a lock, molding, or window that he did not inspect in the drawings and in the actual building with the utmost thoroughness and care.”[23]

Stackpole worked through ten months of 1932 on a monumental pair of sculptures flanking the grand entrance of the Stock Exchange: a male and a female grouping showing the polarity of agriculture and industry, showing in their rounded human shapes the influence of Rivera. Chiseling into 15 short tons (14 t) of Yosemite granite, he wore goggles and a mask. The unveiling ceremony took place in the cold of New Year’s Eve, with Mayor Angelo Rossi joining Stackpole, Pflueger and artisans in smocks.[24]

Stackpole took his son Peter to visit their photographer friend Edward Weston in Carmel in the early 1930s, and the two older men spent the day discussing photography, “the difference between making and taking a photograph, between the intended and the random”.[7] This conversation, and the 1932 exhibit by Group f/64, a collection of innovative photographers such as Weston and Ansel Adams, was later seen as foundational to Peter Stackpole’s conception of photography.[7]

In July 1933, Stackpole completed a model of a design to be incorporated into the San Francisco – Oakland Bay Bridge’s central anchorage on the western side. The anchorage, to be constructed of concrete rising 197 feet (60 m) above the water, was to display over much of its height a bare-chested male figure standing solidly between the two suspension spans. However, Arthur Brown, Jr., Pflueger’s colleague on the Bay Bridge project, did not like the scale of the figure, which belittled the bridge. Engineer Ralph Modjeski agreed, writing “The gigantic figure which is proposed for the centre anchorage is out of place for a structure of this kind and would not harmonize with the end anchorage.”[25] Stackpole’s design was abandoned in favor of a largely flat expanse of poured concrete.

In 1933 and 1934, Stackpole took part in the Public Works of Art Project assignment to paint murals for Coit Tower.[26] Many of the murals were executed in styles reminiscent of Rivera, and Stackpole himself was portrayed in five of them;[27] in one he is shown reading a newspaper announcing the destruction of a Rivera mural in New York.

In 1937, Stackpole received a commission to sculpt his interpretation of Colorado River explorer John Wesley Powell, for display in the Main Interior Building of the U.S. Department of Interior. It was to be a companion piece to Heinz Warneke’s portrayal of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Warneke learned that Stackpole intended a water scene, so he changed his portrayal of Lewis and Clark to be one of them on land. Stackpole and Warneke delivered their stone reliefs in 1940, and the two panels were mounted on either side of the stage of the building’s auditorium.[28]

Noted photographer Peter Stackpole, famous for his photographs of the building of the Bay Bridge in the 1930s and one of the original four staff photographers for Life magazine, has died. He was 83.

Mr. Stackpole died Sunday at Novato Community Hospital of congestive heart failure, his son, Tim Stackpole, said Monday.

Born in San Francisco on June 15, 1913, the son of artists, Mr. Stackpole grew up in Oakland and took up photography in high school when he traded his model airplanes for a friend’s photography equipment. His father, Ralph Stackpole, sculpted the pylons adorning the front of the Pacific Stock Exchange and “Pacifica,” the 80-foot statue for the 1939 World’s Fair on Treasure Island.

Sponsored Links

• Local Singles – Free Pics 1000s of Local Singles Want to Chat! View Pics & Profiles for Free! (true.com)

• The Next Internet Boom Stock Investment With 1,000% Potential Gains (www.stockmauthority.com)

• Credit Cards For Everyone Rebuild Credit Today With A Second Chance Credit Card! (CardWisdom.com)

advertisement | your ad here

After building a darkroom in his mother’s home, Peter Stackpole parlayed his hobby into work for local newspapers.

He is best known to Bay Area residents for his powerful images of the construction of the Bay Bridge. On a ferry ride to visit his father’s studio, he got an inspiration from seeing the bridge towers being built, rising out of the water like majestic monoliths.

His big break came in 1934, when Time magazine paid him $100 for his shot of then-President Herbert Hoover snoozing at a commencement ceremony at UC-Berkeley’s Greek Theatre – a photograph killed by Oakland Tribune publisher William Knowland.

In 1936, Life magazine hired Mr. Stackpole as one of its four original photographers. He worked alongside legendary photographers Alfred Eisenstaedt, Margaret Bourke-White and Thomas McAvoy, launching an illustrious career with Life that lasted 25 years. His work graced 26 covers.

He was the last surviving member of that first Life photo staff.

In 1991, Mr. Stackpole, who had carefully saved negatives from his assignments covering everything from war to Hollywood, lost all but a handful of his work in the Oakland hills fire that consumed his home. He bundled up 50 wartime images and escaped with them.

Mr. Stackpole and his wife, Hebe, lost their Montclair hillside home and everything in it, including a professional darkroom, four enlargers, a dozen cameras, expensive accessories, and negatives and prints from a thousand assignments.

A year after the fire, the photographer said the loss gave him perspective and a fresh outlook.

“If I had five more minutes and more light to see where the stuff was, I might have saved some of my best work,” he said. “But what’s gone is gone and there ain’t a damned thing anyone can do about it.”

Tim Stackpole remembered his father’s creative craftsmanship in building waterproof camera housings in the family basement.

“Media was like putty in his hands,” Tim Stackpole said. The elder Stackpole taught his son how to use lathes to shape Plexiglass. “I came away with the feeling that I could make anything.”

“He was a wonderful person. A wonderful friend,” said Mr. Stackpole’s nephew Tobias van Rossum Daum, who recalled that his uncle was recently busy in his darkroom reprinting crisp images of Errol Flynn from original 60-year-old negatives.

Besides Flynn, Mr. Stackpole photographed Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Alfred Hitchcock, Ingrid Bergman, Orson Welles and Elizabeth Taylor. He became a fixture at Hollywood parties and developed friendships with many film industry luminaries.

His photographs showing the celebrities having fun and relaxing at home with their families were among the first to break from the glamorous Hollywood portraits familiar to fans.

Mr. Stackpole also taught photography at the Academy of Arts College in San Francisco in the 1960s. He also was something of a celebrity at local photo equipment swap meets.

“He’ll be missed in those circles,” van Rossum Daum said.

Mr. Stackpole is survived by his son, Tim, and two daughters

Share this:

Related

The Creative StackpolesDecember 7, 2011With 1 comment

Peter Stackpole and Liz TaylorJuly 6, 2021Liked by 1 person

The Atlantean Grail RisingJanuary 28, 2015

Leave a comment