My 9th grandfather, John Wilson, mentions Zion a number of times. This is very key because John was a co-founder of Harvard that is under attack by Bill Ackman, who wants many colleges to spread pro-Israeli messages. No need, Big A. Sit down!

John Wilson’s son was a ‘First Fruit’ one of nine graduates of Harvard. I am almost certain I sent this post, and others, to Mark Gall, who I considered a good friend since 1997. He was the head of of the Department of Education at the University of Oregon. He ignored me, and other pleas for help in owning literary credibility. He should contact his Alma mater, and make sure I get a honorary degree, in regards to my intellectual contributions that have shed light on recent controversies.. .

John Presco

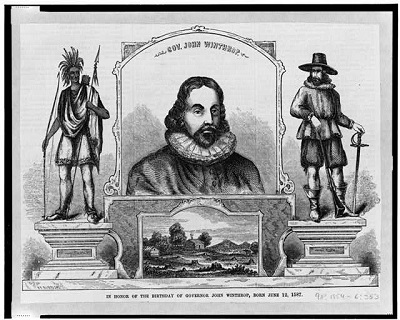

The Protector of Harvard

“Goldman writes. Early Puritan settlers in America understood their “errand into the wilderness” as a fulfillment of God’s covenants. But Goldman argues that most of the seventeenth-century colonial talk about America as “the New Israel” was less about Puritans and more about the Jews. Puritans did not claim that God had turned his favor to New England at Israel’s expense. Rather, as Goldman writes, “New England might have been like Israel in important ways. But it could not be a replacement for the Jews because the covenant with Abraham remained in effect.” The nuances of this belief, the author admits, did not extend to all, or even most, New Englanders. There are copious examples of colonial (and later) theologians and pastors equating America with God’s covenanted people. But the belief that Jews remained in covenant with God was held by Increase Mather and Jonathan Edwards, among others.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alma_mater

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Increase_Mather

Harvard College[edit]

In his autobiography, Increase Mather writes that he was President of Harvard from 1681 until 1701,[1][page needed] but due to charter and organizational changes, his official title varied. On June 11, 1685, he was made Acting President and on July 23, 1686, he was appointed Rector. On June 27, 1692, he finished writing the new college charter and became president.[5] On September 5, 1692, while the Salem trials were still ongoing, Increase Mather was awarded a doctorate of divinity, the first doctorate issued at Harvard, and the last for 79 years.[16]

What I Wrote Yesterday

Posted on December 8, 2019 by Royal Rosamond Press

I wrote the following yesterday from 10:00 to 5:00 P.M. I dropped out of High School and never went to college. I did not do well in English and never passed a spelling test. When I took a break and a walk, my neighbors wondered about me. I seemed to be in a daze, and ignoring them. Some became furious, and tried to destroy me. The same thing happened to Reverend John Wilson. One article I read said, the Massachusetts Bay Company charter was annulled by Charles the second (an ancestor of Princess Diana) because Harvard College was founded. John Eliot founded a Latin School in Roxbury where I lived.

My daughter and her mother went behind my back to create a bond with my sister who destroyed our family history – for money! After getting caught betraying me, this team of treasure hunters have formed a Man Hater club where I am demonized and ostracized. I have been besieged by crazy Christian and Anarchist Tribes who want to destroy me. John Wilson can relate. I suspect a lot of drunks and fornicators got on board ships for America looking for a free meal. The Puritans banned Christmas because it was a Roman orgy.

I am going to adopt this pen name.

John Wilson Rosamond

New England First Fruits

Posted on December 8, 2019 by Royal Rosamond Press

(Gali Tibbon/AFP/Getty)

Uh-oh!

My 9th grandfather, John Wilson, mentions Zion a number of times. This is very key because John was a co-founder of Harvard that is under attack by Bill Ackman, who wants many colleges to spread pro-Israeli messages. No need, Big A. Sit down!

John Presco

The Protector of Harvard

“Goldman writes. Early Puritan settlers in America understood their “errand into the wilderness” as a fulfillment of God’s covenants. But Goldman argues that most of the seventeenth-century colonial talk about America as “the New Israel” was less about Puritans and more about the Jews. Puritans did not claim that God had turned his favor to New England at Israel’s expense. Rather, as Goldman writes, “New England might have been like Israel in important ways. But it could not be a replacement for the Jews because the covenant with Abraham remained in effect.” The nuances of this belief, the author admits, did not extend to all, or even most, New Englanders. There are copious examples of colonial (and later) theologians and pastors equating America with God’s covenanted people. But the belief that Jews remained in covenant with God was held by Increase Mather and Jonathan Edwards, among others.

A retired US Army lieutenant colonel is organizing an armed convoy next week to the Texas border to, he says, hunt down migrants crossing into the US from Mexico. Hundreds of people already say they are coordinating travel plans for the convoy on Telegram as tensions continue to rise between the state and federal government over immigration.

Pete Chambers, the lieutenant colonel who says he was a Green Beret, appeared on far-right school-shooting conspiracist Alex Jones’ InfoWars show on Thursday to outline plans for the Take Back Our Border convoy, which has been primarily organized on Telegram.

es Archives

See the article in its original context from

December 25, 1983, Section 7, Page 4Buy Reprints

TimesMachine is an exclusive benefit for home delivery and digital subscribers.

About the Archive

This is a digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive, before the start of online publication in 1996. To preserve these articles as they originally appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them.

Occasionally the digitization process introduces transcription errors or other problems; we are continuing to work to improve these archived versions.

ISRAEL IN THE MIND OF AMERICA

By Peter Grose. Illustrated. 361 pp. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. $17.95.

THE history of America and that of the Jewish people have commingled for more than three centuries. The New Jerusalems and New Zions the Puritans aimed to build in New England attest to the fervid identification of these early settlers with the Old Testament. And the hectored Jews of Europe long beheld the new land as Canaan itself. Today, the United States and Israel are bound together in strategic cooperation, and the developments that led to their present relationship represent American politics at its best – and worst – as well as the resolve of a ravaged people to survive devastation.

Peter Grose, a senior fellow of the Council on Foreign Relations and its director of Middle Eastern studies, relates the American side of the tale with clarity and brio in ”Israel in the Mind of America.” It is difficult to do justice to the liveliness, intricacies and subtleties of this resplendent book, which is based on painstaking research. Sympathetic to the struggle to establish a Jewish homeland but never uncritical, Mr. Henry F. Graff , a professor of history at Columbia University, is the editor of the forthcoming ”The Presidents: A Reference History.” Grose confidently negotiates the history of the politics and diplomacy with a ready eye for quotation and anecdote. He is able to evoke in a paragraph or two the essence and foibles of the many principal actors, giving the book the quality of a pageant. The array of characters is colorful. There is, for instance, Cotton Mather, who in 1696 prayed earnestly for ”the conversion of the Jewish Nation, and for . . . having the happiness at some time or other, to baptize a Jew.” And there are the gentiles and Jews with other hopes. Two of the most notable are John McDonald, a Presbyterian pastor in Albany during the War of 1812, who beseeched all who would listen to him to help restore the Jews to their ancient homeland, and, a few decades later, Mordecai Noah of Philadelphia, a Sephardic Jew and sometime United States diplomat, who promoted through his newspaper a proto-Zionist dream of returning the Jews to the Promised Land.

At the middle of the 19th century, nevertheless, the possibility of re-establishing Zion seemed foolish fancy. Indeed, among American Jews – as among Jews everywhere – the traditional cry of ”next year in Jerusalem” remained the pious incantation it had been for nearly 2,000 years. Besides, to most of the 150,000 Jews in America on the eve of the Civil War, the possibility of a revived homeland in Palestine was of little interest. To the rest of the population, the subject was not even a matter of discussion. Jews were irrelevant in a nation whose people often preened themselves as the new chosen people. Although anti-Semitism existed (and exists) in America, Mr. Grose does not touch on the subject save in passing. Nor does he call attention to the Jewish community’s steady acculturation – the indispensable requirement for the American-Jewish interplay that proved essential for the ”return.”

ADVERTISEMENT

But by the end of the 19th century, a small but growing roster of Jewish figures was beginning to have influence on the national scene, just as a new era in the resuscitation of Palestine as a Jewish homeland had opened in Europe. The utopian vision of Theodor Herzl seized the imagination of Jews in Russia and Poland, increasingly battered by pogroms – 300 of them reported in the American press between 1903 and 1906 alone. The hundreds of thousands of East European Jews who fled to the United States stirred anxieties in the older American-Jewish community. The insecurity of the established Jews about their own place in American society made them fiercely anti-Zionist, even as support for Zionism was rising among the new arrivals.

Henry Morgenthau, the father of the future New Deal Secretary of the Treasury, declared boldly that Zionism was ”wrong in principle and impossible of realization . . . an Eastern European proposal . . . which, if it were to succeed would cost the Jews of America most of what they had gained of liberty, equality and fraternity.” But Louis D. Brandeis, one of Morgenthau’s contemporaries and a legendary voice for social justice, became a missionary for Zionism. Before World War I ended, the ceaseless work in Europe of Chaim Weizmann had led to the Balfour Declaration – Britain’s pledge to help re-establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Mr. Grose’s review of the love-hate relationship between Weizmann and Brandeis speaks brilliantly to the place that historians must reserve for the individual actors even as they quest to grasp the forces of history.

Most of ”Israel in the Mind of America” deals with the story after 1940. While the Holocaust was greeted by American Jews with disbelief at first, the rest of America met the news mostly with indifference – a complex amalgam of ignorance, social anti-Semitism in the State Department and the immense gulf between national ideals and national will. Mr. Grose spares no one in assessing the American Government’s response to the plight of the Jews during World War II and after. He sees Franklin Roosevelt as a simplifier of issues, trimming his sails constantly to the winds he confronted – Arab or Jewish or bureaucratic. He sees Harry S. Truman as bent on doing the right thing – supporting the ideal of a Zionist state – but constantly wary of being taken in by the Jewish leaders who lobbied him incessantly. He regards Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long and some other public officials as anti-Semites, whose views were finally defeated in the play of forces within Truman’s White House.

MR. GROSE also recounts the contribution of David K. Niles, a Presidential assistant of Polish-Jewish background, whose work in pressing the case for the recognition of Israel in 1948 was Herculean. A holdover from the Roosevelt Administration, Niles is depicted as supplying the determinative argument that Clark Clifford, then a young Truman adviser, presented in a memorable confrontation with George C. Marshall, Robert Lovett and others in the State Department over the nagging issue of recognition. But Niles is only one of the figures whose work is spotlighted here. The roles of Samuel Rosenman, Benjamin V. Cohen and Truman’s army friend, Eddie Jacobson, have never been so fully elucidated. And the roles played by non-Jews, including particularly Maj. Gen. John H. Hilldring and Earl G. Harrison, are given their due.

Making significant use of documents in Israeli archives that have recently been published, Mr. Grose relates, with fresh details, the critical labors late in November 1947 to round up votes at the United Nations in support of the partition of Palestine. Every arm, it seems, was twisted. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, accompanied by his colleague Frank Murphy, paid a fruitful visit to the Philippine Ambassador in Washington. Niles, through a friend in Boston, worked on Spyros Skouras, the motion-picture magnate, to influence his friends in Greece (to no avail, it proved). Bernard Baruch, hardly a friend of Zionism, was also induced by Niles to pitch in. According to Mr. Grose, Baruch ”ended up by telling the French delegate to his face that a French vote against partition would mean the end of all American aid to France.” France voted for the partition resolution, which passed with only two votes to spare.

“What gets us to the enemy quickly is find, fix, and finish,” Chambers told Jones. “That’s what we did in Syria when we took out ISIS really quick. Now we don’t have the authorities to finish, so what we can do is fix the location of where the bad guys are and pair up with law enforcement who are constitutionally sound.”

While this kind of right-wing chatter doesn’t always amount to anything, on Telegram the main Take Back Our Border channel now has over 1,000 members and is being used as a place to plan and share information about the convoy, as well as three rallies taking place in Texas, California, and Arizona next week. The convoy will reportedly begin on Monday, January 29, and participants currently say they are planning on driving to Shelby Park in Eagle Pass, Texas, where the Texas National Guard is currently in a standoff with the US Border Patrol.

The convoy has been promoted by Texas state representative Keith Self, who appeared on Fox Business to speak about the event and posted a link to a news article from the conspiracy-focused The Gateway Pundit about the convoy on his X account.

In state-specific subgroups for attendees to organize rideshares and other resources, members are outlining their plans about where along the route they will join up with the convoy. The main part of the convoy will begin in Virginia and will make its way through Florida, Louisiana, and on to Texas.

ADVERTISEMENT

One group member suggested others bring “kits” to the planned rallies so that “if stuff goes down you will be able to protect yourselves and help out.” Another user responded: “I’m in Missouri. I’ll be ready and have my kit full.”

Some Telegram users have compared this moment to the American revolution of 1776.

“There is a point where we are going to have to get our hands dirty,” one member wrote in the Texas group. “I’ve dealt with MANY bullies in my life, and I’ve never been able to reason with them. The one universal language bullies understand is when you push them back.”

Another poster shared a quote from far-right figure Jack Posobiec saying the country is on “the verge of civil war with the government,” while one member claimed, without evidence, that the Border Patrol is “letting known terrorists into the US.”

A promotional video for the convoy on the website begins with alarms sounding and the words “invasion alert” flashing over what appears to be night-vision footage of people crossing the border. The video also calls back to previous convoys, such as the People’s Convoy that rolled into Washington, DC, in 2022 to protest Covid-19 lockdowns. However, the administrators of the Telegram group and the convoy’s website are careful to say this will be a peaceful protest and that only “law-abiding citizens” are welcome. The convoy’s website says it’s looking for everyone to join the effort, including “all active and retired law enforcement and military veterans.”

FEATURED VIDEOAli Wong & Steven Yeun Answer the Web’s Most Searched Questions

MOST POPULAR

The convoy is being organized as tensions over the US–Mexico border escalated this week, when the US Supreme Court lifted an order by a lower court and sided with President Joe Biden’s administration to rule that Border Patrol agents could remove razor wire installed by the Texas National Guard and state troopers. Texas governor Greg Abbott has defied the ruling as the Texas National Guard and state troopers have continued to roll out wire at Shelby Park on the banks of the Rio Grande in Eagle Pass. Republicans have backed Abbott, who stated on January 24 that the state’s right to “defend and protect” itself against an “invasion” of migrants “is the supreme law of the land and supersedes any federal statutes to the contrary.”

More than two dozen Republican governors, Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, and former president Donald Trump have come out in support of Abbot.

“Biden is, unbelievably, fighting to tie the hands of Governor Abbott and the State of Texas, so that the Invasion continues unchecked,” Trump wrote on Truth Social. “Texas has rightly invoked the Invasion Clause of the Constitution, and must be given full support to repel the invasion.”

“The feds are staging a civil war, and Texas should stand their ground.” Representative Clay Higgins, a GOP congressman from Louisiana, posted on X after the Supreme Court issued its ruling.

The post was shared widely in online communities populated by far-right extremists, including on The Donald, a far-right message board where some of the planning for the January 6 Capitol riot took place.

“There’s no other way to interpret removing a border than outright treason,” a member of The Donald wrote. “The Supreme Court justices who agreed to this deserve to be executed as traitors.” Another added in relation to the judges: “Traitors deserve to die.”

On X on Thursday, the hashtags #CivilWar and #StandwithTexas were both trending.

Do you know anything about the Take Back Our Border convoy or its organizers? Send David Gilbert an email at david.gilbert@wired.com or DM him on X (Twitter) @daithaigilbert for his Signal and WhatsApp number.

During the hourlong interview, Chambers blamed migrants for the fentanyl crisis, which he described as “chemical warfare,” and he called the Biden administration the enemy of the people. Jones described Abbott’s January 24 statement as “the new Declaration of Independence.” Chambers told Jones how he was planning to use the same techniques he claims he used while in the US military fighting the Islamic State to target migrants crossing the border. He echoed Abbott, and described the effort as “domestic internal defense.”

Chambers also said that one of the stops on the convoy will be the One Shot Distillery and Brewery in Dripping Springs, Texas, which is owned by Phil Waldron, a former army colonel. Waldron was central to plotting the January 6 insurrection, when he circulated a 38-page PowerPoint presentation to members of Congress that, among other things, called for Trump to declare a state of emergency and seize voting machines. Waldron was listed as an unindicted coconspirator in Trump’s Georgia election-interference case.

And while much of this kind of violent rhetoric is never acted upon, there have been a growing number of incidents beyond January 6 where online comments have been followed up with real-world action, including when a man targeted an FBI office after slamming the agency for searching Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home on Truth Social.

Efforts in Congress to find a compromise on border funding appeared to collapse earlier this week, but yesterday Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell told reporters that talks were still “ongoing.”

Cross© provided by RawStory

Atrucker convoy heading down to the southern border is using apocalyptic rhetoric to describe its desire to hunt down migrants illegally entering the United States.

Vice reports that the convoy, which is calling itself “God’s Army,” is launching a campaign called “Take Our Border Back” to drive undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers out of the country.

And the rhetoric about representing God in this quest isn’t just metaphorical, as they believe they have a divine calling to force foreigners out of the country, writes Vice.

Want more breaking political news? Click for the latest headlines at Raw Story.

“This is a biblical, monumental moment that’s been put together by God,” one convoy member said during a recent organizing call.

On that same call, writes Vice, another organizer argued that these actions needed to be taken because “we are besieged on all sides by dark forces of evil.”

The group’s desire for drastic actions was recently heightened after the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could remove razor wire at Eagle Pass, where a migrant woman and two children drowned while trying to cross the border.

What’s so American about Christian Zionism?

By Dan Hummel | May 9, 2018

(Gali Tibbon/AFP/Getty)

God’s Country: Christian Zionism in America

By Samuel Goldman

University of Pennsylvania, 2018

Benjamin Netanyahu’s visit to the White House in March made headlines for his comparison of Donald Trump to Cyrus, the ancient Persian king who ended Israel’s Babylonian captivity. Speaking of the U.S. decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of the state of Israel, Netanyahu placed Trump in a distinguished lineage including Lord Balfour and Harry Truman, saying, “Mr. President, this will be remembered by our people through the ages.”

Indeed, a popular anecdote in the annals of American-Israeli relations tells of a retired President Truman being introduced to a Jewish Theological Seminary audience. As he is presented by his old business partner, Eddie Jacobson, as “the man who helped create the State of Israel,” Truman bristles and replies: “What do you mean, ‘helped to create’? I am Cyrus! I am Cyrus!”

Both the current Israeli prime minister and President Truman invoked the name of Cyrus as shorthand for an instrument of God chosen to restore the Jews to their Promised Land. In the flurry of Christian Zionist activity in the Trump era, the Cyrus motif still carries weight. Cyrus, and the biblical story of Esther, are perhaps the predominant typologies in contemporary Christian Zionist thinking.*

Samuel Goldman, who teaches political science and directs the Loeb Institute for Religious Freedom at George Washington University, makes the case in his new book, God’s Country: Christian Zionism in America, that a significant tradition in American Protestantism has understood the United States as a collective Cyrus, destined to help return the Jewish people to their Promised Land as a fulfillment of God’s covenants with Abraham.

Less well known—and Goldman’s prime concern—are the predecessors to modern evangelical Christian Zionists: sixteenth-century British theologians, seventeenth-century Puritan divines, eighteenth-century American revolutionaries, and nineteenth- and twentieth-century liberal Protestants. He weaves these characters into a history of American Christian Zionist thought from the seventeenth century to the present and gives a semblance of coherence and understanding for readers who are curious about the roots of American Cyrus-philia and the possible consequences of its invocation by political leaders.

Unlike today, when U.S. engagement in the Middle East is a matter of course, American interest in Palestine before the twentieth century was chiefly theological. Goldman reminds us that out of the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation emerged popular interest in the fate of the Jewish people and a new covenantal thinking that tied the destiny of gentile nations to Jewish settlement in Palestine. Protestant theologians, by reading the Hebrew and early Christian prophetic books “literally” instead of allegorically, came to believe that ancient Israel had never enjoyed complete domination over the land to which they were promised, and that God would yet fulfill those promises with the physical descendants of Abraham.

It was not just theology but Protestant theology that created the “unique connection” with Israel in the “American imagination,” Goldman writes. Early Puritan settlers in America understood their “errand into the wilderness” as a fulfillment of God’s covenants. But Goldman argues that most of the seventeenth-century colonial talk about America as “the New Israel” was less about Puritans and more about the Jews. Puritans did not claim that God had turned his favor to New England at Israel’s expense. Rather, as Goldman writes, “New England might have been like Israel in important ways. But it could not be a replacement for the Jews because the covenant with Abraham remained in effect.” The nuances of this belief, the author admits, did not extend to all, or even most, New Englanders. There are copious examples of colonial (and later) theologians and pastors equating America with God’s covenanted people. But the belief that Jews remained in covenant with God was held by Increase Mather and Jonathan Edwards, among others.

This conviction, Goldman argues, outlasted the Puritans and became embedded in American political thought. Elias Boudinot, a former president of the Continental Congress, wondered in 1816 whether “God had raised up these United States in these latter days, for the very purpose of accomplishing his will in bringing his beloved people to their own land.” By 1891, the conservative evangelical William E. Blackstone, whom Louis Brandeis called the “father of Zionism,” could produce more than 400 signatures from the circles of American political and social elites—Supreme Court justices, senators, congressmen, and business tycoons—to urge President Benjamin Harrison to become like Cyrus and facilitate the Jewish people’s return to their homeland.

This American fascination with Israel was mediated through the Bible. For Boudinot and Blackstone, God’s continued covenant with the Jewish people did not, of course, seamlessly translate into Protestant respect for Judaism. Most theologians expected Jews to convert “from unbelief” as a precondition for their restoration to Palestine. Even for those who did not, Judaism and political Zionism were tolerated only as imperfect tools of God’s will. America’s covenantal responsibilities encapsulated more than Jewish political restoration and extended to fulfilling the Apostle Paul’s prophecy of Romans 11:26 that “all Israel will be saved.”

Likewise, the Israel that American Christians invoked hardly resembled the land or people of Palestine in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Americans preferred vivid biblical and national metaphors to describe the Holy Land and their relationship to it; Cyrus was but one of the most prominent. The United States was the “eagle” of Exodus 19, according to Boudinot, delivering Jews from exile. Palestine, described by Herman Melville as a place “[w]here vulture unto vulture calls,” evoked the unsettled American West. For famed Protestant minister Harry Emerson Fosdick, who toured Palestine in 1926, the Arab inhabitants were destined to become like the Native Americans. “[T]he Arab has not the faintest chance of competition,” he concluded, in the presence of industrious Jewish migrants. John Haynes Holmes, a Unitarian minister and friend of Fosdick, called for Jews confronting violence in Palestine to be “a ‘suffering servant’ of God for his work of justice and peace upon the earth” and to resist acting as “a nation ‘like all the nations.’” Goldman observes that “Holmes was subtly and perhaps unintentionally implying that Israel’s duty was to engage in a collective imitation of Christ.”

These metaphors, so powerful in linking America to Jewish restoration, also exposed blind spots in future American diplomacy, both in attitudes toward Palestine and in the prescriptive roles for Arabs and Jews that undergirded American thinking. Goldman is reticent to explore the links between Christian Zionist attitudes and American policy toward the Middle East in the twentieth century, even as he illustrates how pervasive Protestant thinking was in American political thought. Other historians, including Paul Boyer, Douglas Little, and Melani McAlister, have more fully examined the ramifications of Protestant theology on American policy toward Palestine’s Arab inhabitants. In short, the special link between Israel and the land of Palestine, and the vaunted place of Jewish restoration in Christian eschatology, often came at the expense of the non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine.

Goldman is more engaged in tracing the contours of liberal Protestant opinion toward Jews in Europe. The legacy of supersessionist theology, which declared that the church had assumed the blessings once reserved for Israel while Jews suffered under their rejection of Jesus as Messiah, blunted Protestant concern for European anti-Semitism. “To the extent that liberal Protestants protested the Third Reich in its first years,” Goldman writes, “it was in defense of so-called non-Aryan Christians—converts to Christianity or their descendants, who were still considered Jews under Nazi racial laws.” The seeming paradox of elevating the role of the Jewish people in God’s ultimate plans while remaining disengaged with contemporary Jewish suffering was not a uniquely American Protestant phenomenon, but its development was especially consequential in the United States, which after 1945 became more engaged than ever in Middle East diplomacy.

The “Judeo-Christian civilization” that Americans began to articulate in the 1930s, and which received a major boost in the waging and winning of World War II, opened new avenues for American Zionism and informed successive U.S. administrations’ understandings of Israel and the Middle East. But “Judeo-Christianity” also advanced a civil religious concept that celebrated God chiefly as the bestower of democratic and individual rights. This God—“the universal deity of liberal Protestantism” in Goldman’s account—was not the God who chose Israel as his covenanted people, but a God who had used the Jewish people as a “testimony to a religious perspective to which all people had access.” The postwar ecumenical leaders had less patience for covenantal chosenness and the nationalism of political Zionism. The drift of liberal and mainline Protestantism from its Christian Zionist roots, Goldman argues, was due in part to this shifting theological emphasis, as well as Israel’s transformation from “David to Goliath” after its victory in the Arab-Israeli War of June 1967.

Even so, for a smaller group of postwar liberal Protestants, humanitarian and geopolitical considerations fueled a vigilant Christian Zionism. Reinhold Niebuhr, the most outspoken postwar Protestant supporter of Israel until his death in 1971, was a bellwether, basing his concerns for Israel on morality and political realism. Unlike other liberal Protestants, it did not take the Holocaust to spur his humanitarian considerations—Niebuhr had come to believe in the need for a Jewish state in Palestine in the 1930s. Like the Protestants of old, he acknowledged Jewish covenantal exceptionalism, though he did not believe in the literal fulfillment of biblical prophecies. Niebuhr’s long career and defense of Israel bridge the Christian Zionist tradition that Goldman traces from the sixteenth century with the late-twentieth century Christian Zionist movement dominated by evangelical Christians.

In Goldman’s telling, the alliance between evangelicals and Israel after 1980 was “more continuous with the liberal Christian Zionism of the postwar years than it appeared to be”—a judgment that too swiftly ignores the novel ways evangelicals developed their Zionism, including the adoption of prosperity theology to give material weight to God’s promise to “bless those who bless” Israel. Indeed, the historical lesson Goldman seeks to draw from emphasizing continuity in American Christian Zionism is left undeveloped. Today’s evangelical Christian Zionists can point to a historical and distinguished pedigree; their skeptics can trace the long theological moves that kept covenantal theology and prophecy interpretation alive in American Protestantism long past its preferred expiration date. While empathetic to Christian supporters of Israel, Goldman refrains from judgment on which narrative is closer to the truth. While he admits that “not everything old is good,” he situates current Christian Zionists as the inheritors of the tradition and, to use 2018 language, normalizes Christian Zionism in American thought—not to endorse it, but to stimulate “civil discussion.”

Yet it is true that God’s Country tells, with notable clarity and academic rigor, a version of the story close to what Christian Zionists repeatedly tell themselves. Mike Pence uttered a less nuanced version of that story in his January speech to the Knesset. The vice president invoked the memories of the Pilgrims, George Washington, John Adams, and Harry Truman to affirm that “down through the generations, the American people became fierce advocates of the Jewish people’s aspiration to return to the land of your forefathers.” Goldman has provided the most erudite, accessible, and concise guide to this unfamiliar but relevant theological history; perhaps he has also supplied the tools to critique it anew.

Daniel G. Hummel is a Robert M. Kingdon Research Fellow at the Institute for Research in the Humanities, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“These latest developments have aroused civil war fantasies on fringe forums, as well as on the social media accounts of GOP lawmakers and right-wing political commentators,” reports Vice. “And this all means that the border convoy is garnering more interest than it might have done a couple of weeks ago. The convoy’s crowdfunder on GiveSendGo has raked in more than $30,000 just this week, totaling nearly $50,000 by Friday morning.”

Leave a comment