Charles von Habsburg, King of Romans, launched a holy crusade against the indiginous people of the Americas, and devestated their culture and religion in what ammounted to genocide. Quint was the greatest parasite the world had ever known. He brought sickness to these people that he sicked his savage dogs upon, and took their gold. Charles fueled the ongoing violent conversion of Jews to Christianity with the wealth he stole from America. How dare Bishop say this in regards to my President.

“People of faith cannot be made second-class citizens because of their religious beliefs. . . . Our parents and grandparents did not come to these shores to help build America’s cities and towns, its infrastructure and institutions, enterprise and culture, only to have their posterity stripped of their God given rights.”

The Republican Christian-right dread the influx of people from Mexico – that Quint conquered – because their vote could put the Democrats in the White House – till doomsday. This is why the New Inqustion is going after condoms. This is purely a political attack aimed at weakening a secular Democracy. This attack comes from a foreigner, the Pope in Rome -who buthchered my Protestant Huguenot ancestors when the Rosemondt family alas saw the light and became Protestants. They fled the monsters of the Virgin Cult, and came to America where they built churches. And the ministers of these churches had wives!

So, put on your plastic rain gear, because the blood and guts are going to fly, as usual, when Viriginal Men go into a rage when folks don’t buy their holier-then-thou attitude, when normal folk dare question their authority to make everyone in the world a second class citizen! Not in my Democracy!

Jon the Nazarite

The White House is ready to soften its decision to require religious institutions to cover birth control in their employee health insurance.

President Obama’s decision has been denounced by Catholics, Republicans and even some Democrats. Amid the controversy, CBS News has learned that as early as Friday, President Obama could announce some new guidelines dealing with the contraception policy.

Sources tell CBS News the White House will not back off the administration goal to provide increased access to birth control for women, but it will provide religious institutions additional details on how to comply with the law.

The exact nature of the compromise remains unclear, but could largely follow what exists in a majority of states, like in Illinois where DePaul University, the largest Catholic university in the country, offers an employee health plan that does cover contraception. Georgetown University offers a similar plan.

The policy has sparked an internal debate within the White House that at one point pitted some of the male advisers, including Vice President Biden and former chief of staff Bill Daley, against some female advisers. In the end, the president decided to move forward on the rule, which is already law in 28 states.

The president was meeting with the Prime Minister of Italy in the Oval Office Thursday, but when peppered with questions on the red-hot controversy over contraception, he refused to comment.

The administration is doing a macabre dance around what is quite clearly a constitutional Inquisition. In telling Catholics that our religion is not as important as a woman’s “choice,” we are learning that JFK was wrong. Apparently, you cannot be both a Catholic and a law-abiding citizen under the Obama administration because you can obey the law only if you violate your religious principles, or pay a hefty fine for exercising your constitutional right to free exercise.

Unless Obama changes his position, all Catholics – regardless of their views on “choice” – should deny him their vote. If we don’t, we are accepting a seat at the back of the national bus.

I am with Christine on the issue of contraception. So are most Catholic women. The Church’s idea of “natural family planning” is way too unrealistic.

But there is nothing absurd or illogical about having a moral code that says that sex before marriage is irresponsible. One only has to see, as any teacher can tell you, the consequences to those children born to unwed teenagers and other single mothers, basically doomed to poverty, often neglected and abused.

OK, it is an ideal in a society that would rather imitate chimpanzees than saints.

So if we must, give the sexually active their pills and devices. It is better than abortion as birth control.

Charles V (Spanish: Carlos I, German: Karl V., Italian: Carlo V, Dutch: Karel V, French: Charles Quint; 24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 and, as Charles I, of the Spanish Empire from 1516 until his voluntary retirement and abdication in favor of his younger brother Ferdinand I and his son Philip II in 1556.

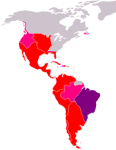

As the heir of three of Europe’s leading dynasties—the House of Habsburg of the Habsburg Monarchy; the House of Valois-Burgundy of the Burgundian Netherlands; and the House of Trastámara of the Crowns of Castile & Aragon—he ruled over extensive domains in Central, Western, and Southern Europe; and the Spanish colonies in North, Central, and South America, the Caribbean, and Asia.

Charles was the eldest son of Philip the Handsome and Joanna the Mad. When Philip died in 1506, Charles became ruler of the Burgundian Netherlands, and his mother’s co-ruler in Spain upon the death of his maternal grandfather, Ferdinand the Catholic, in 1516. As Charles was the first person to rule Castile-León and Aragon simultaneously in his own right, he became the first King of Spain (Charles co-reigned with his mother Joanna, which was however a technicality given her mental instability).[3] In 1519, Charles succeeded his paternal grandfather Maximilian as Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria. From that point forward, Charles’s realm, which has been described as “the empire on which the sun never sets”, spanned nearly four million square kilometers across Europe, the Far East, and the Americas.[4]

Much of Charles’ reign was devoted to the Italian Wars against the French king, Francis I, and his heir, king Henry II, which although enormously expensive, were militarily successful due to the undefeated Spanish tercio and the efforts of his prime ministers Mercurino Gattinara and Francisco de los Cobos y Molina. Charles’ forces re-captured both Milan and Franche-Comté from France after the decisive Habsburg victory at the Battle of Pavia in 1525,[5] which pushed Francis to form the Franco-Ottoman alliance. Charles’ rival Suleiman the Magnificent conquered Hungary in 1526 after defeating the Christians at the Battle of Mohács. However, the Ottoman advance was halted after they failed to capture Vienna in 1529.

Aside from this, Charles is best known for his role in opposing the Protestant Reformation.[6] In addition to the German Peasants’ War against the Empire, several German princes abandoned the Catholic Church and formed the Schmalkaldic League in order to challenge Charles’ authority with military force. Unwilling to allow the same religious wars to come to his other domains, Charles pushed for the convocation of the Council of Trent, which began the Counter-Reformation. The Society of Jesus was established by St. Ignacio de Loyola during Charles’ reign in order to peacefully and intellectually combat Protestantism, and continental Spain was spared from religious conflict largely by Charles’ nonviolent measures.[7] In Germany, although the Protestants were personally defeated by Charles at the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547, he legalized Lutheranism within the Holy Roman Empire with the Peace of Augsburg. Charles also maintained his alliance with Henry VIII of England, despite the latter splitting the Church of England from Rome and violently persecuting Catholics.

In the New World, Charles oversaw the Spanish colonization of the Americas, including the conquest of both the Aztec Empire and the Inca Empire. The rapid Christianization of New Spain was attributed to the miracle of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Uncomfortable with how his viceroys were governing the Americas vis-à-vis the Native Americans, Charles consulted figures such as Francisco de Vitoria and Bartolomé de las Casas on the morality of colonization which las Casas vehemently opposed with his Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Charles V also provided five ships to Ferdinand Magellan and his navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano, after the Portuguese captain was repeatedly turned down by Manuel I of Portugal. The commercial success of Magellan’s voyage (the first circumnavigation of the Earth) temporarily enriched Charles by the sale of its cargo of cloves and laid the foundation for the Pacific oceanic empire of Spain, and along with Ruy López de Villalobos, began Spanish colonization of the Philippines.

In the 16th century, the phrase (Spanish: El imperio en el que nunca se pone el sol) was first used to describe the Spanish Empire. It originated with a remark made by Fray Francisco de Ugalde to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (Charles I of Spain), who as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and king of Spain, had a large empire, which included many territories in Europe and vast territories in the Americas.

The phrase gained added resonance during the reign of Charles’s son, King Philip II of Spain. The Philippines was obtained by Spain in 1565. When King Henry of Portugal died, Philip II was recognised as King of Portugal in 1581, resulting in a personal union of the crowns. He now reigned over all his father’s possessions (except the Holy Roman Empire) and the Portuguese Empire, which included territories in South America, Africa, Asia and islands in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans.

. On that first trans-Atlantic voyage, Columbus and his sailors were greeted by the Arawak people of the Bahamas, who were kind and curious about the Spanish sailors, and offered food, water, and gifts. Yet, in his log, Columbus wrote that “. . . They would make fine servants . . . With fifty men we could subjugate them all, and make them do whatever we want.” In 1495, Columbus and crew rounded up 1,500 Arawak men, women, and children, from which group they selected 500 “best specimens” to take to his sponsors; of those people, some 200 died en route to Spain.[4] At the Spanish Court, Columbus presented the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabel, with the captured Arawaks, gold trinkets, parrots, and other exotic things. Impressed with the human and material bounties yielded by the first expedition, they commissioned Columbus for a second expedition, and provided 17 ships, some 1,500 soldiers, cavalry, and weapons (cannon, crossbows, guns, and attack dogs). In 1493, Columbus returned to the New World and claimed Spanish ownership of the island of Hispaniola (contemporary Haiti and the Dominican Republic) from the indigenous Taíno people.[citation needed] The Spanish Monarchs granted Columbus the governorship of the new territories, and financed more of his trans-Atlantic journeys

A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies[1] (Spanish: Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias) is an account written by the Spanish Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas in 1542 (published in 1552) about the mistreatment of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas in colonial times and sent to then Prince Philip II of Spain.

One of the stated purposes for writing the account is his fear of Spain coming under divine punishment and his concern for the souls of the Native Peoples. The account is one of the first attempts by a Spanish writer of the colonial era to depict the unfair treatment that the indigenous people endured during the early stages of the Spanish conquest of the Greater Antilles, particularly the island of La Hispaniola. Las Casas’s point of view can be described as being heavily against some of the Spanish methods of colonization, which, as he describes, have inflicted a great loss on the indigenous occupants of the islands.

His account is largely responsible for the passage of the new Spanish colonial laws known as the New Laws of 1542, which abolished native slavery for the first time in European colonial history and led to the Valladolid debate.

The images described by Las Casas were later depicted by Theodore de Bry in copper plate engravings that helped expand the Black Legend against Spain.

During Charles’ reign, the territories in New Spain were considerably extended by conquistadores like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, who caused the Aztec and Inca empires to fall in little more than a decade. Combined with the Magellan expedition’s circumnavigation of the globe in 1522, these successes convinced Charles of his divine mission to become the leader of Christendom that still perceived a significant threat from Islam. The conquests also helped solidify Charles’ rule by providing the state treasury with enormous amounts of bullion. As the conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo observed: “We came to serve God and his Majesty, to give light to those in darkness, and also to acquire that wealth which most men covet.”[21] In 1550, Charles convened a conference at Valladolid in order to consider the morality of the force used against the indigenous populations of the New World, which included figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas.

Charles V is credited with the first idea of constructing an American Isthmus canal in Panama as early as 1520.[22]

The Spaniards were also skilled at breeding dogs for war, hunting and protection. The introduction of the Mastiff, wolf hound and sheep dog was unexpectedly effective as a psychological weapon against the natives, who, in many cases, had never seen domesticated dogs, though many indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere did, indeed, have domestic dogs; these include, but are not limited to: the current Southwestern US, Aztec and other Central American peoples, the inhabitants of the Arctic/Tundra regions (Inuit, Aleut, Cree), and possibly some South American groups. During the conquest of the Americas, Spanish conquistadors used Spanish Mastiffs and other Molossers in battle against Native Americans, like the Taínos, Aztecs, or Mayans. These specially trained dogs were feared by the Indians because of their strength and ferocity.

The strongest war dogs, broad-mouthed breeds of mastiff specifically trained for battle, were used against almost nude troops. The Spanish conquistadors used armoured dogs that had been trained to kill and disembowel when they invaded the land controlled by South American natives.[18]

From 1580–1670 the Bandeirantes focused on slave hunting, then from 1670–1750 they focused on mineral wealth. Through these expeditions, the Bandeirantes also expanded Portuguese America from the small limits of the Tordesilhas Line to roughly the same territory as current Brazil.

In the conquest of Mexico the expedition of Hernan Cortes had to supply their own materials, weapons and horses. Some were supported by government, and too local governors backed by richmen. After receiving notice from Juan de Grijalva of much gold in the area of what is now Tabasco, the governor of Cuba, Diego de Velasquez, made a decision to send a larger force than had previously sailed, and appointed Cortes as Captain-General of the Armada. Cortes then applied all of his funds, mortgaged his estates and borrowed from merchants and friends to outfit the ships that would sail under his command. Velasquez may have contributed some to the effort, but the government of Spain had no financial input into this undertaking.[19]

[edit] Disease

Aztecs dying of smallpox, (“The Florentine Codex” 1540–85)

While technological and cultural factors played an important role in the victories of the conquistadors, this was facilitated by diseases brought from the old world, especially smallpox. The defeat of the American Indian civilizations seems were produced too in several cases, by their population crisis. Some identify genocidal acts by the Europeans as the main cause. Some attribute it to the introduction of new diseases and still others to both factors.

The first foreing diseases contracted by indigenous people were carried to distant tribes and villages. This typical path of disease transmission moved much faster than the advancing Spaniards.

Epidemic disease devastating the native population is commonly cited as the primary reason for the decline in population of the Native Americans because of their lack of immunity to new diseases brought from old world.[20] Often overlooked is that there were few relationships among the vast dispersed indigenous peoples of the Americas. Most peoples lived in isolated communities, with only limited trade contact and no regular communication. Limited trading was the only constant contact between most New World cultures.

In practice, the Inquisition would not itself pronounce sentence, but handed over convicted heretics to secular authorities.[10] The laws were inclusive of proscriptions against certain religious crimes (heresy, etc.), and the punishments included death by burning. Thus the inquisitors generally knew what would be the fate of anyone so remanded, and cannot be considered to have divorced the means of determining guilt from its effects.[11]

Tribunals and institutions

Before the 12th century, the Catholic Church already suppressed heresy, usually through a system of ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but without using torture[1] and seldom resorting to executions.[4][5] Such punishments had a number of ecclesiastical opponents, although some countries[which?] punished heresy with the death penalty.[6][7]

In the 12th century, to counter the spread of Catharism, prosecution of heretics by secular governments became more frequent. The Church charged councils composed of bishops and archbishops with establishing inquisitions (see Episcopal Inquisition). The first Inquisition was established in Languedoc (south of France) in 1184.

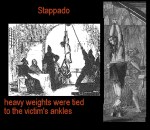

Two priests demand a heretic to repent as he is tortured.

In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX (reigned 1227–1241) assigned the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order. They used inquisitorial procedures, a legal practice common at that time. They judged heresy alone, using the local authorities to establish a tribunal and to prosecute heretics. After the end of the twelfth century, a Grand Inquisitor headed each Inquisition. Grand Inquisitions persisted until the 19th century.[8]

By the start of the 16th century the Catholic Church had reached an apparently dominant position as the established religious authority in western and central Europe dominating a faith-landscape in which Judaism, Waldensianism, Hussitism, Lollardry and the finally conquered Muslims al-Andalus (the Muslim-dominated Spain) hardly figured in terms of numbers or of influence. When the institutions of the church felt themselves threatened by what they perceived as the heresy, and then schism of the Protestant Reformation, they reacted. Paul III (Pope from 1534 to 1549) established a system of tribunals, administered by the “Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Universal Inquisition”, and staffed by cardinals and other Church officials. This system would later become known as the Roman Inquisition. In 1908 Pope Saint Pius X renamed the organisation: it became the “Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office”. This in its turn became the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith[9] in 1965, which name continues to this day[update].

The victim’s hands were bound behind the back. They were then yanked up to the ceiling of the torture chamber by a pulley and a rope. Dislocation ensued. Xtians preferred this method, as it left no visible marks of torture. Heavy weights were often strapped to the victim to increase the pain and suffering.

Squassation was a more extreme form of the torture. This method entailed strapping weights as much as hundreds of pounds, pulling limbs from their sockets. Following this, the xtian inquisitor would quickly release the rope so they would fall towards the floor. At the last second, the xtian inquisitioner would again yank the rope. This dislocated virtually every bone in the victim’s body. Four applications were considered enough to kill even the strongest of victims.

Xtian clergy delighted in the tearing and ripping of the flesh. The Catholic church learned a human being could live until the skin was peeled down to the waist when skinned alive. Often, the rippers were heated to red hot and used on women’s breasts and in the genitalia of both sexes.

Breast Rippers

Loss of human life:

Salzburg, Austria, 1677-1681 over 100 murdered

Basque region of the Pyrenees; 1608, Lawyer Pierre de Lancre was sent to the region to “root out and destroy those who worshipped Pagan Gods.” Over 600 tortured and murdered.

Witch judge Henri Boguet c. 1550-1619 sent some 600 victims to their deaths in Burgundy, many of them young children who were systematically tortured and then burned alive.

A pregnant woman was burned alive and from the trauma, she gave birth before she died. The baby was tossed back into the flames.

Swedish town of Mora, 1669, more than 300 murdered. Among them, 15 children. 36 children between the ages of 9 and 15 were made to run the gauntlet and were beaten with rods upon their hands once a week for an entire year. Twenty of the youngest children, all under the age of 9 were whipped on their hands at the church door for 3 sundays in succession. Many more were severaly beaten for witchcraft offenses.

In Scotland, under the rule of Oliver Cromwell, a total of 120 in a single month were murdered in 1661. Estimates of the total dead have been as high as 17,000 between 1563 and 1603.

In Würzburg, Germany, the Chancellor wrote a graphic account in the year of 1629:

“…there are three hundred children of three or four years, who are said to have had intercourse with the Devil. I have seen children of seven put to death, and brave little scholars of ten, twelve, fourteen and fifteen years of age…”

Between the years of 1623 and 1633, some 900 “witches” were put to death throughout Würzburg. This was largely maintained by the Jesuits.

The Chronicler of Treves reported in 1586 that the entire female population of two villages was wiped out by inquisitors. Only two women were left alive.

Noted cases included the Knights Templar, Joan of Arc who was chained by the neck, hands and feet and locked in a cramped iron cage, Galileo, who stated that the Earth revolved around the Sun and was not the center of the universe as the church taught(See above).

The above accounts were taken from Cassel Dictionary of Witchcraft by David Pickering.

On Sunday, March 12th, 2002, the Pope John Paul II apologized for the “errors of his church for the last 2000 years.”

As Holy Roman Emperor, Charles called Martin Luther to the Diet of Worms in 1521, promising him safe conduct if he would appear. Initially dismissing Luther’s theses as “an argument between monks”, he later outlawed Luther and his followers in that same year but was tied up with other concerns and unable to take action against Protestantism.

1524 to 1526 saw the Peasants’ Revolt in Germany and in 1531 the formation of the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League. Charles delegated increasing responsibility for Germany to his brother Ferdinand while he concentrated on problems elsewhere.

In 1545, the opening of the Council of Trent began the Counter-Reformation, and Charles won to the Catholic cause some of the princes of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1546 (the year of Luther’s natural death), he outlawed the Schmalkaldic League (which had occupied the territory of another prince). He drove the League’s troops out of southern Germany and at the Battle of Mühlberg defeated John Frederick, Elector of Saxony and imprisoned Philip of Hesse in 1547. At the Augsburg Interim in 1548 he created an interim solution giving certain allowances to Protestants until the Council of Trent would restore unity. However, Protestants mostly resented the Interim and some actively opposed it. Protestant princes, in alliance with Henry II of France, rebelled against Charles in 1552, which caused Charles to retreat to the Netherlands.

About the same time as in southern France the Inquisition was introduced into Aragon. In 1233 Pope Gregory X. commissioned the Archbishop of Tarragona to appoint inquisitors; and by the fourteenth century there was a grand inquisitor in Aragon. In 1359, when some Jews who had returned to Judaism after conversion fled from Provence to Spain, King Pedro IV. of Aragon empowered the inquisitor Bernard du Puy to sentence them wherever found. One of the most prominent personages of the Aragonese Inquisition was the grand inquisitor or inquisitor-general Nicolas Eymeric. He sentenced the Jew Astruc da Piera, accused of sorcery, to imprisonment for life; and Ramon de Tarrega, a Jew who accepted baptism and became a Dominican, and whose philosophic works Eymeric stigmatized as heretical, he kept imprisoned for two years, until compelled by Pope Gregory XI. to liberate him.

The New Inquisition.

The New or Spanish Inquisition, introduced into the united kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, and Navarre by Ferdinand V. and Isabella the Catholic, was directed chiefly against converted Jews and against Jews and Moors. During the cruel persecutions of 1391 many thousands of Jewish families accepted baptism in order to save their lives. These converts, called “Conversos,” “Neo-Christians” (“Christaõs Novos”). or “Maranos,” preserved their love for Judaism, and secretly observed the Jewish law and Jewish customs. Many of these families by their high positions at court and by alliances with the nobility excited the envy and hatred of the fanatics, especially of the clergy. After several unavailing attempts to introduce the Inquisition made successively, from the reign of Juan II., by the Bishop of Osma, Alfonso de Espina, and by Niccolo Franco, nuncio of Sixtus IV. at the Spanish court, the Dominicans applied to the young queen Isabella. Alfonso de Hojeda and the papal nuncio exerted all their energies, and succeeded in 1478 in obtaining from Sixtus IV. a bull authorizing Ferdinand and Isabella to choose sundry archbishops, bishops, and other persons, both clericals and laymen, for the purpose of conducting investigations in matters of faith. The king readily gave his consent to a scheme which promised to satisfy his cupidity, while the queen hesitated to sanction its establishment in Castile. It was early in Sept., 1480, that Isabella, urged by Alfonso de Hojeda, Diego de Marlo, Pedro de Solis, and other ecclesiastical dignitaries, finally affixed her signature to the document which established the Inquisition in her dominions. On Sept. 27, 1480, two Dominicans, Juan de San Martin and Miguel de Morillo, were appointed the first inquisitors.

The newly appointed inquisitors together with their assistant, Dr. Juan Ruiz de Medina, and with Diego Merlo, went first to Seville, where the feeling aroused was divided. The “good” Christians and the populace gave the visitors a ceremonious reception; but many nobles, several of whom had intermarried with the Maranos, were terrified at the new arrivals. A number of prominent and wealthy Maranos of Seville, Utrera, Carmona, Lorca, and other places, including Diego de Susán, father of the beautiful Susanna; Benadeva, father of the canon of the same name; Abolafia “el Perfumado,” farmer of the royal taxes; Pedro Fernandez Cansino; Alfonso Fernandez de Lorca, Juan del Monte, Juan de Xerez, and his father Alvaro de Sepulveda the Elder, and many others, convened and agreed to oppose the inquisitors. They intended to distribute arms and to win over the people by bribes. An old Jew of their number encouraged them. The conspiracy, however, was betrayed and suppressed in its inception (details of this “Conjurados de Sevilla” are given in Fita, “La España Hebræa,” I. 71-77, 184-196).

First Seizure of Maranos.

Many Maranos, on receiving news of the introduction of the Inquisition, went with all their possessions to Cadiz, in the hope of finding protection there; but the inquisitors addressed (Jan. 2, 1481) an edict to Rodrigo Ponce de Leon, Marquis of Cadiz, and to all dukes, counts, grand masters of orders, and knights, as well as to the alcaldes of the cities of Seville, Cordova, Jerez de la Frontera, Toledo, and others in Castile, ordering them to seize and give up all Maranos hidden among them, and to confiscate their property. All persons who refused to obey this edict were to be punished by excommunication and by forfeiture of their property, offices, and dignities (Fita, l.c. p. 77). The bands of fugitive Maranos were very numerous; in the territory of the Marquis of Cadiz alone there were 8,000, who were transported to Seville and delivered to the Inquisition. Even during the early days of 1481 many of the wealthiest, most prominent, and learned Maranos, municipal councilors, physicians, etc., had been apprehended, and it had been deemed necessary to transfer the tribunal to the castle of Triana near Seville.

This tribunal, the object of fear and terror for nearly 300 years, began its work; and on Feb. 6, 1481, the first auto da fé at Seville was held with a solemn procession on the Tablada. Six men and women were burned at the stake, probably the same persons whom Alfonso de Hojeda had accused of desecrating an image of Jesus. This zealous Dominican preached at this first auto da fé; but he did not live to see a second one, as he was one of the first victims of the plague which was then raging in Andalusia. A few days later three of the wealthiest and most prominent men of Seville, Diego de Susán (a “gran rabi,” with a fortune of 10,000,000 maravedis), Manuel Sauli, and Bartolome de Torralba, mounted the “quemadero,” as the stake was called. Many other members of the conspiracy mentioned above were burned soon after: Pedro Fernandez Benadeva; Pedro Fernandez Cansino and Gabriel de Zamora, the two last-named being municipal councilors of Seville; Abolafia “el Perfumado,” reputed to be a scholar; Medina el Barbudo, meat commissary at Seville; the municipal councilor Pedro de Jaen and his son Juan del Monte; Aleman Poca Sangre, progenitor of the Alemanes; the wealthybrothers Aldafes, who had been living in the castle of Triana; Alvaro de Sepulveda the Elder and his son Juan de Xerez; and others from Utrera and Carmona. The immense wealth of all the condemned was seized by the royal treasury. At Seville there was at least one auto da fé every month; 17 Maranos were burned on March 26, 1481; many more, a few weeks later; and by the following November nearly 300 had perished at the stake, while 79 were condemned to imprisonment for life. The Inquisition held office also at Cordova and in the archbishopric of Cadiz, where many Jewish heretics, mostly wealthy persons, were burned during the same year.

The Inquisition, in order to set a trap for the unhappy victims, issued a dispensation and called upon all Maranos guilty of observing Jewish customs to appear voluntarily before the court, promising the repentants absolution and enjoyment of their life and property. Many appeared, but they did not obtain absolution, until, under the seal of secrecy and under oath, they had betrayed the name, occupation, dwelling, and mode of life of each of the persons they knew to be Judaizers, or had heard described as such. A large number of unfortunates were thus entrapped by the Inquisition. On the lapse of this decree all those who had been betrayed were summoned to appear before the tribunal within three days. Those that did not attend voluntarily were dragged from their houses to the prisons of the Inquisition. Then a law was issued, indicating in thirty-seven articles the signs by which backsliding Maranos might be recognized. These signs were enumerated as follows:

Signs of Judaism.

(see Llorente, “Histoire de l’Inquisition,” i. 153, iv. Supplement, 6; “Boletin Acad. Hist.” xxii. 181 et seq.; “R. E. J.” xi. 96 et seq., xxxvii. 266 et seq.).

If they celebrate the Sabbath, wear a clean shirt or better garments, spread a clean tablecloth, light no fire, eat the food [“ani”] which has been cooked overnight in the oven, or perform no work on that day; if they eat meat during Lent; if they take neither meat nor drink on the Day of Atonement, go barefoot, or ask forgiveness of another on that day; if they celebrate the Passover with unleavened bread, or eat bitter herbs; if on the Feast of Tabernacles they use green branches or send fruit as gifts to friends; if they marry according to Jewish customs or take Jewish names; if they circumcise their boys or observe the “hadas” [a Babylonian superstition], that is, celebrate the seventh night after the birth of a child by filling a vessel with water, throwing in gold, silver, pearls, and grain, and then bathing the child while certain prayers are recited; if they throw a piece of dough in the stove before baking; if they wash their hands before praying, bless a cup of wine before meals and pass it round among the people at table; if they pronounce blessings while slaughtering poultry, cover the blood with earth, separate the veins from meat, soak the flesh in water before cooking, and cleanse it from blood; if they eat no pork, hare, rabbits, or eels; if, soon after baptizing a child, they wash with water the spot touched by the oil; give Old Testament names to their children, or bless the children by the laying on of hands; if the women do not attend church within forty days after confinement; if the dying turn toward the wall; if they wash a corpse with warm water; if they recite the Psalms without adding at the end: “Glory be to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost,” etc.

It was easy for the Inquisition, with this mode of procedure, to entrap more and more Maranos. From Seville, the only permanent tribunal, it sent its officers to Cordova, Jerez de la Frontera, and Ecija, in order to track the fugitives and especially to confiscate their property. The two inquisitors at Seville were so cruel that complaints were made to Sixtus IV., who addressed a brief (Jan. 29, 1482) to the royal couple, amending the bull of Nov. 1, 1478, and expressing his dissatisfaction. He declared that but for consideration for their majesties he would depose Miguel de Morillo and Juan de San Martin. He refused a request to appoint inquisitors for the other countries of the united kingdom; nevertheless, hardly two weeks later (Feb. 11, 1482) he appointed Vicar-General Alfonso de San Capriani inquisitor-general for the kingdoms of Castile and Leon, and seven other clericals, including Thomas de Torquemada (Turrecremata) as inquisitors.

A Sanbenito.(After Picart.)Ferdinand and Isabella gave no heed to the pope’s urgent recommendation to treat the Maranos more humanely; and they still more strongly disapproved his giving absolution to heretics condemned by the tribunal. Upon this subject Queen Isabella addressed an autograph letter to Sixtus IV., which he answered at length (Feb. 23, 1483). While recognizing her piety, he hinted that the queen was urged to proceed so rigorously against the Maranos “by ambition and greed for earthly possessions, rather than by zeal for the faith and true fear of God.” Still, he made many concessions. Although, as he expressly says in the bull of May 25, 1483, he was the only power to whom final appeal could be made in matters of faith, yet, at the request of the Spanish sovereigns, he appointed the Archbisbop of Seville, Inigo Manrique, judge of appeals for Spain. This, however, did not prevent the vacillating pope from issuing a few months later (Aug. 2) the bull “Ad Futuram Rei Memoriam,” in which he commanded that all Maranos who had repented at Rome and had done penance should no longer be persecutedby the Inquisition. The fact that he had permitted as many copies as possible to be made of this bull did not prevent him from repealing it eleven days later (Aug. 13). By way of further concession to the royal couple the pope appointed as officials of the Inquisition only clericals of pure Christian descent and orthodox Catholics in no degree related to Maranos.

Thomas de Torquemada.

On Oct. 17, 1483, Thomas de Torquemada, then sixty-three years of age and prior of a monastery at Segovia, his native city, was appointed inquisitor-general. His chief endeavor was to make the Inquisition more effective. Tribunals were established in quick succession at Cordova, Jaen, and Ciudad Real. At Cordova, seat of the oldest tribunal next to Seville, the first inquisitors were Pedro Martinez de Barrio and Alvar Gonzalez; and one of the first to be condemned was Pedro Fernandez de Alcaudete, treasurer of a church (Ad. de Castro, “Judios en España,” p. 118; “Boletin Acad. Hist.” v. 401 et seq.). The first inquisitors at Jaen were Juan Garcia de Canas, chaplain to their majesties, and Juan de Yarca, prior of a monastery at Toledo. The tribunal at Ciudad Real, whose first inquisitors were Pedro Diaz de Costana and Francisco Sanchez de la Fuente, existed only two years. From Feb. 6, 1484, to May 6, 1485, ten autos da fé were held in that city, the largest being celebrated Feb. 23-24, 1484, and March 15, 1485. On Feb. 23 about 26 Maranos of either sex suffered at the stake, among them Alvaro de Belmonte, Pero Çarça, Maestre Fernando (known as “el Licenciado de Cordova”), and Maria Gonsales la Pampana. Juan Gonsales Pampana, husband of the last-named, was burned in effigy on the following day together with 41 others, some of whom, like him, had fled, and some of whom had died. On March 15, 1485, not less than 8 were burned alive and 54 in effigy. One of the former was Juan Gonsales Escogido, who was reputed to be a rabbi and “Confesor de los Confesos” (Process of Maria Gonsales la Pampana and of Juan G. Escogido, published, after the acts of the Inquisition, in “Boletin Acad. Hist.” xx. 485 et seq., xxii. 189 et seq.). In May, 1485, the tribunal of Ciudad Real was transferred to Toledo.

Various Manners of Torturing During the Inquisition.(After Picart.)Conditions of Confession.

In order to give more uniformity and stability to the tribunal, Torquemada drafted an inquisitorial constitution, “Compilacion de las Instrucciones,” containing twenty-eight articles, to which several additions were subsequently made. It provided for a respite of thirty or forty days for those accused of Judaizing, and that all who voluntarily confessed within that time should, on payment of a small fine and on making presents to the state treasury, remain in possession of their property. They had to make their confession in writing before the inquisitors and several witnesses, conscientiously answering all questions addressedto them concerning the time and duration of their Judaizing. Thereupon followed the public recantation, which could be made in secret only in rare cases. Those that confessed only after the expiration of the respite were punished by having their property confiscated or by imprisonment for life (“carcel perpetuo”) according to the gravity of the offense. Maranos under twenty years of age who admitted that they were obliged by their parents, relations, or other persons to observe Jewish ceremonies were not subject to confiscation of their property, but were compelled to wear for a certain length of time the sanbenito (see Auto da FÉ). Those that confessed after the publication of the testimony, but before sentence was pronounced, were admitted to “reconciliation,” but were sentenced to imprisonment for life, while those that concealed part of their guilt were condemned to the stake. If a suspected Marano could not be convicted of apostasy he was to be tortured; if he confessed on the rack, he was condemned to death as a Judaizer; but if he recanted his confession or resorted to untruths, he was again subjected to torture.

The prisons of the Inquisition—which, with the instruments of torture, still exist in some cities in Spain, as in Saragossa—were small, dark, damp apartments, often underground. The food of the captives, furnished at their own cost, was both meager and poor; and their only beverage was water. Complaining aloud, crying, or whimpering was rigorously repressed. The punishment inflicted by the Inquisition was imprisonment, either for a stated time or for life, or death by fire. If impenitent the condemned was tied to the stake and burned alive; if penitent he was strangled before being placed on the pile. Flight was considered equivalent to a confession or to a relapse (“relapso”) to Judaism. The property of the fugitive was confiscated, and he himself was burned in effigy (“Compilacion de las Instrucciones del Oficio de la S. Inquisicion,” Madrid, 1667; Llorente, l.c. i. 175 et seq.; “R. E. J.” xi. 91 et seq.).

In Aragon, Catalonia, and Valencia.

With Torquemada the Inquisition was introduced into Catalonia (Oct. 17, 1483); as to Valencia, it had existed there since 1420, the inquisitor being the Dominican Juan Cristobal de Gualbes (Galves). In Aragon the Inquisition could be instituted only with the consent of the Cortes; and its introduction according to the new organization was determined (April, 1484) only after violent debates. Gaspar Juglar, and Pedro Arbues, canon of the metropolitan church of Saragossa, were appointed inquisitors for Aragon, and Pedro d’Epila and Martin Iñigo for Valencia. On May 10, 1484, the first auto da fé at Saragossa was held under the presidency of Maestre Julian, who, according to Lea, is identical with Gaspar Juglar. He was soon after poisoned by the Conversos or Maranos.

Death of Pedro Arbues.

There was violent opposition to the Inquisition throughout Aragon as well as in Catalonia; not only the Conversos and persons descended from Conversos or connected with them by marriage, but Christians also considered the Inquisition as destructive of their liberties. There was so much opposition that the assembled Cortes determined to send a deputation to protest to the king, who remained inflexible, even refusing the enormous sum which the Maranos offered to induce him to revoke the decree confiscating their property. The Maranos in despair then assassinated the inquisitor Arbues. When the murder became known, the populace proceeded to the ghetto in order to kill the Jews and Maranos, and a fearful massacre would have followed had not the young Archbishop Alfonso de Aragon appeared in time to pacify the people.

This conspiracy incited the Inquisition to horrible activity. Between Dec. 15, 1485, and the beginning of the sixteenth century one or two autos da fé were held nearly every month at Saragossa. Especial severity was exercised toward the instigators of and participants in the conspiracy. Juan de Esperanden first had his hands chopped off, and was then dragged with Vidal de Urango to the market-place, and beheaded. Both were quartered and finally burned June 30, 1486. On Dec. 15 a similar fate befell the scholarly Francisco de S. Fé (a descendant of Jerome de S. Fé), who was held in high esteem by the governor of Aragon. Juan de la Abadia, who had attempted suicide, was dragged through the streets, quartered, and burned Jan. 21, 1487. Four weeks later the Jesuit Juan Martinez de Rueden, in whose possession anti-Christian books in Hebrew were found, was burned; and on April 10, 1492, his relative, the widow of Antonio de Rueda of Catalayud, who had kept the Sabbath and had regularly eaten “ḥamyn” (“potagium vocatum ḥamyn”= or “shalet”), met a similar fate. Gaspar de S. Cruce and Juan Pedro Sanchez, who had escaped to Toulouse, were burned in effigy. During the last fifteen years of the fifteenth century more than fifty autos da fé were held at Saragossa, and during the year in which the Jews were expelled from Spain not less than nine were celebrated there; hundreds of members of the most wealthy and prominent families—those of Sanchez, Caballeria, Santangel, Paternoy, Monfort, Ram, Almaçan, and Clemente—were either burned or sentenced to imprisonment for life (Henry C. Lea, “The Martyrdom of S. Pedro Arbues,” New York, 1889; Rios, “Hist.” iii. 615-634; “R. E. J.” xi. 84 et seq.).

The Maranos of Toledo likewise resisted the introduction of the Inquisition; and several of them conspired to kill the inquisitor. In May, 1485, the inquisitors Pero Diaz de la Costana and Vasco Ramirez de Ribera entered Toledo. On June 2 an attack was made on one of them; but he was protected by the populace, who, falling upon the conspirators, De la Torre and his four companions, strangled and hanged them. The inquisitors granted a respite of forty days to the Maranos, which was extended to seventy, in order to afford them the opportunity to give themselves up voluntarily to the Inquisition. At the same time they called together the rabbis, and demanded from them, under oath and on pain of dire punishment, that they pronounce the great excommunication upon all the Jews, and that they recall it only after the Jews had denounced all Maranos following Jewish customs. Some frightenedJews are said to have betrayed their coreligionists; others, poor, degraded, and filled with hatred against the apostates, denounced them as Judaizers, giving false testimony. Eight or more of these false witnesses were tortured with hot irons at the command of Queen Isabella (Pulgar, “Cron. de los Reyes Catolicos,” iii., li. 100; “Boletin Acad. Hist.” xi. 297, xxiii. 407).

In Toledo.

There was no lack of victims. On Feb. 12, 1486, occurred the first auto da fé in Toledo in the presence of a large concourse of the people of the city and of the surrounding country. On this day 750 persons were received into the Church; on April 2, 900; on June 11, 750. On Aug. 16 of the same year, 25 persons, including Alfonso Cota and other prominent men, were burned alive; on the following day the pastor of Talavera and a cleric, both of whom were adherents of Judaism, were burned; and on Oct. 15 several hundred deceased persons, whose property had been confiscated by the state, were burned in effigy. At an auto da fé held Dec. 10 following, 950 persons received absolution. On Jan. 15 and March 10, 1487, 1,900 Judaizers were readmitted to the Church. On May 7, 23 persons, including a canon, were burned alive; on July 25, 1488, 37 persons, and two days later 6 Judaizing clericals, shared the same fate. On May 24, 1490, 21 persons suffered at the stake, and 11 were sentenced to imprisonment for life. At a great auto da fé on the following day the bones of 400 Judaizers and many Hebrew books formed the pile for a woman who wished to die as a Jewess, and who expired with the word “Adonai” on her lips. On July 25, 1492, eight days before the expulsion, 5 Maranos were led to the stake, and many others were condemned to imprisonment for life. At an especially large auto da fé held July 30, 1494, 16 persons from Guadalajara, Alcalá de Henares, and Toledo were burned, and 30 were condemned to life imprisonment. In 1496 three autos da fé were held, and in the following year two. All the condemned persons were of course deprived of their property (on Toledo see “Boletin Acad. Hist.” xi. 285 et seq., xx. 462).

Before the end of the fifteenth century there were nearly a dozen tribunals in Spain. The one at Guadalupe, province of Estremadura, was established as early as that at Toledo; many Maranos were living there; and the inquisitor, Nuno de Arevato, proceeded rigorously against them. The tribunal existed there for a few years only; but during that time, beginning with 1485, seven autos da fé were held, at which 52 Judaizers were burned alive, 25 were burned in effigy together with the bones of 46 deceased persons, 16 were condemned to imprisonment for life, and many were sentenced to wear the sanbenito, and were deprived of their property.

Opposition in Catalonia.

The Catalonian cities, too, stubbornly opposed the newly organized Inquisition; and in 1486 there were riots at Teruel, Lerida, Barcelona, and Valencia, during which the tribunals were destroyed. It was not until 1487 that the inquisitor-general Torquemada was able to appoint Alfonso de Espina of Huesca inquisitor of Barcelona. De Espina began his activity on Jan. 25, 1488, with a solemn auto da fé, the first victim being the royal official Santa Fé, a descendant of a well-known Jew-hater, Jerome de Santa Fé. On May 2, 1489, the wife of Jacob Monfort, the former Catalonian treasurer, was burned in effigy; and on March 5 and 23, 1490, Louis Ribelles, a surgeon of Falces, together with his children and his daughter-in-law, was condemned to imprisonment for life; his wife Constancia was burned on March 12 at Tarracona, where a large auto da fé was held on July 18, 1489; and on March 24, 1490, Gabriel Miro (magister in artibus et medicina), his wife Blanquina, the wealthy Gaspar de la Cavalleria, and his wife were burned in effigy. Simon de Santangel and his wife, whom their own son denounced to the Inquisition at Huesca as Judaizers, were burned on July 30, 1490, at Lerida.

Conforming Jews Involved.

In Catalonia the activity of the Inquisition was restricted to a few autos da fé held at Barcelona and some other cities; and the number of victims was limited. The Inquisition was all the more active in Old Castile, where Ferdinand and Isabella, with Torquemada, did their utmost, not to confirm the Maranos in their new faith, but to destroy them and to deprive them of their property. On June 19, 1488, the tribunal of Valladolid held its first auto da fé, at which 18 persons who had openly confessed Judaism were burned alive. The first inquisitors at Segovia were Dr. de Mora and the licentiate De Cañas; and the first victim to be publicly burned was Gonzalo de Cuellar, whose property to the amount of 393,000 maravedis was confiscated by the state treasury. Involved in the process against him were his Jewish relatives, Don Moses de Cuellar, the latter’s son Rabbi Abraham and his brother, of Buytrago, as well as Juan (Chalfon) Conbiador (= “changer”) and Isaac Herrera, both of Segovia (“Boletin Acad. Hist.” xxiii. 323 et seq.). At Avila the first victims were the Francos, who were accused of having murdered the child La Guardia. Between 1490 and the end of the century more than 100 persons were burned at Avila as “Judios” or Judaizers, the majority being natives of Avila, with a few from Arevalo, Oropesa, and Almeda; 70 were punished otherwise (see lists of the condemned in Fita, l.c. i. 51 et seq.).

Torquemada accused even bishops who were of Jewish descent, as Juan Arias Davila, Bishop of Segovia, and Pedro de Aranda, Bishop of Calahorra. During his term of fifteen years he condemned more than 8,000 Jews and Maranos to be burned alive, and more than 6,000 in effigy. His successor, the scholarly Dominican Diego Deza, the friend and patron of Columbus, was equally cruel, condemning many Maranos. On Feb. 22, 1501, a great auto da fé was held at Toledo, at which 38 persons were burned, all of them from Herrera. On the following day 67 women of Herrera and Alcocen were burned at Toledo; a few days previously about 90 Maranos of Chillon were burned at Cordova; and on March 30, 1501, 9 persons were burned at Toledo, while 56 young men and 87 young women were condemned to life imprisonment. In July of the same year 45 persons were burned at Seville, among them a young woman 25 years of age, who was considered a scholar and who read the Bible with her fellowsufferers (“Boletin Acad. Hist.” xl. 307 et seq.; “R. E. J.” xxxvii. 268, xxxviii. 275). Diego Deza, of Jewish descent on his mother’s side, despite his cruelty to the Jews, was himself accused of Judaizing. As he was continually ill, Juan, Bishop of Vigue, was appointed grand inquisitor of Aragon, and Francisco de Ximenes, Archbishop of Toledo, was appointed grand inquisitor of Castile, even during Deza’s lifetime.

Diego Rodriguez Lucero.

Deza’s most pliable tool was Diego Rodriguez Lucero, the inquisitor of Cordova, who enjoyed the special favor of Ferdinand and Isabella. For his espionage and confiscations he received from them “ayudas de Costa” to the value of 20,000 and 25,000 maravedis. He was a monster of cruelty and committed so many atrocities that Gonzalo de Avora wrote to the royal secretary Almazan on July 16, 1507. “Deza, Lucero, and Juan de la Fuente have dishonored all provinces; they have no regard either for God or for justice; they kill, steal, and dishonor girls and women to the disgrace of the Christian religion.” In order to curry favor with King Ferdinand, Lucero brought accusations against all persons suspected of being of Jewish blood, regardless of their station in life, and extorted confession on the rack. One of these victims was the young Archdeacon de Castro, whose mother was of an old Christian family, while his father was a Marano; his revenues, amounting to 300,000 maravedis, were divided among Lucero, Cardinal Carvajal, the royal treasurer, and the king’s secretary. A bachelor of divinity, Membreque by name, was accused of having publicly preached on the doctrines of Judaism, whereupon Lucero procured a list of the persons who had listened to his sermon, and all of them, 107 in number, were burned alive.

Attempts to Check Lucero.

No one was sure of his life. The prisons were crowded, and large numbers of prisoners were taken to Toro, the seat of the supreme council of the Inquisition. Lucero’s principal object was the confiscation of property, as the Bishop of Cordova and many dignitaries of the city stated in a complaint against him which they sent to the pope. The most prominent persons of Cordova requested the inquisitor-general Deza to depose Lucero; and an appeal was made to Queen Juana and her husband, Philip of Austria, who then lived in Flanders. On Sept. 30, 1505, Philip and Juana addressed a cedula to Deza, in which they sharply criticized Lucero’s proceedings and suspended the Inquisition until their arrival in Spain. Though this missive was disregarded, Philip’s coming filled the Maranos with new hope. At Rome they had bought the Curia; and they had offered 100,000 ducats to King Ferdinand during his sojourn at Valladolid if he would suspend the Inquisition until the arrival of the young couple. At first matters looked very bright for their attempts, and Lucero’s conduct was the object of an investigation. Unfortunately, Philip died suddenly, and Lucero, now emboldened, asserted that most of the knights and nobles of Cordova and other cities were Judaizers, and had synagogues in their houses. The highest dignitaries were treated by him like “Jewish dogs.” He accused the pious Hernando de Talavera, Archbishop of Granada, who had Jewish blood in his veins, and his whole family, of Judaizing. His relatives were imprisoned, and he himself, who once had been the confessor of Queen Isabella, was compelled with many other converts to go barefoot and bareheaded in procession through the streets of Granada. The exposure brought on an attack of fever, and he died five days later.

Ferdinand, who reascended the throne after Philip’s death, was obliged to dismiss Deza, in order to stem the movement against the Inquisition at Cordova; and Ximenes, Archbishop of Toledo, was appointed inquisitor-general in his place (June, 1507). The supreme council of the Inquisition, headed by Ximenes, decided in May, 1508, to imprison Lucero; and he was taken in chains to Burgos and confined in the castle there. The “Congregacion Catolica,” consisting of the most pious and learned bishops and other high ecclesiastics of the whole country, was commissioned to investigate the charges against Lucero, and at a solemn session held at Valladolid Aug. 1, 1508, it gave orders for the liberation of all those imprisoned on the charge of Judaizing (Henry C. Lea, “Lucero, the Inquisitor,” in “Am. Hist. Review,” ii. 611-626; Rios, “Hist.” iii. 483 et seq.).

Attitude of Charles V.

The grand inquisitor Cardinal Ximenes de Cisneros was not more tolerant toward the Maranos than his predecessor had been; he caused many to be burned and many thousands to be punished by forcing them to perform various acts as penance. A few years after his death the victims of incessant persecution, profiting by the opposition of Castile to the young Charles I. (afterward Emperor Charles V.), sent a deputation, consisting of the most prominent Maranos, to King Charles in Flanders, requesting him to restrict the powers of the Inquisition and to have testimony heard in public. As an inducement to the king they offered him a very large sum, said to have amounted to 800,000 gold thalers. In order to win over the Curia, Gutierrez sent his nephew, Luis Gutierrez, to Rome, where other converts, among them Diego de las Casas and Bernaldino Diez, were working for them. The tolerant Pope Leo X. granted them a bull such as they desired, and which some persons claim to have seen in a Spanish translation. As soon as Charles heard of the intended bull, he made every effort to prevent its publication. He sent word to Leo X. by his envoy Lope Hurtado de Mendoza that the complaints of the converts as well as the expostulations of a few Spanish prelates and of misinformed or interested persons deserved no credit, and that the inquisitor-general for Castile, Adrian, formerly Bishop of Tortosa, who had been appointed May 4, 1518, was much more inclined to moderation than to severity. Furthermore, he stated that the converts had sent a complaint to him against the servants of the Inquisition, and had offered to him, as formerly to his grandfather, a large sum to restrain the tribunal. Moreover, Charles affirmed that under no conditions would he allow a bull restraining the Inquisition to be published in his kingdom. The pope acceded to Charles’s demand, issuing thebrief of Oct. 12, 1519; and the Inquisition pursued its course unchecked (“Boletin Acad. Hist.” xxxiii. 307 et seq.; “R. E. J.” xxxvii. 269 et seq.). Nevertheless, Charles would have restrained the Inquisition in his dominions had not his chancellor Selvagio, who advocated the plan, died. After his death Charles became an ardent protector of the Inquisition. Down to 1538 there were tribunals at Seville, Cordova, Jaen, Toledo, Valladolid, Calahorra, Llerena, Saragossa, Valencia, Barcelona, Cuenca, Granada, Tudela, and at Palma in the Balearic Isles, where the first auto da fé was held in 1506, and 22 Judaizers were burned in effigy. Several Jews were burned alive in 1509 and 1510, and 62 Judaizers were burned in effigy in the following year.

Under the Philips.

The cruel Philip II. favored the Inquisition. One of his grand inquisitors was Fernando de Valdes, formerly Archbishop of Seville, who was unsurpassed for his cruelty. The Cortes in vain repeatedly remonstrated against the terrible abuses of the tribunals and demanded that they be restricted. Philip III. was very weak, and during his reign the Inquisition proceeded still more shamelessly after the unsuccessful attempt of the Duke de Olivares to check it. Under this king as well as under his successor, Philip IV., Jews were burned throughout the realm; every tribunal held at least one great auto da fé each year. The largest number occurred in Andalusia, at Seville, Granada, and Cordova. The fanatical populace gathered in greater multitudes at the autos than at theaters and bull-fights. Every auto was like a great popular festival, to which the knights and representatives of neighboring cities were solemnly invited, the windows of the houses nearest to the quemadero being reserved for them. Great autos were held at Cordova on Dec. 3, 1625; May 3, 1655; and June 29, 1665. Among the large number burned at the first of these was Manuel Lopez, who obstinately resisted all attempts at conversion. At the last-mentioned auto the city spent, according to the bills preserved in the municipal archives, not less than 392,616 maravedis for food served to the inquisitors and their servants, the dignitaries, knights and invited guests. The auto lasted from seven in the morning till nine at night; and 55 Judaizers were burned, 3 of them alive. In addition 16 were burned in effigy. Under Philip IV. a tribunal was instituted at Madrid, the new capital, and on July 4, 1632, the first auto was held for Judaizers in celebration of the delivery of Elizabeth of Bourbon. One of the largest autos at Madrid took place on June 30, 1680, in the presence of King Charles II. and his young wife. In the previous year, between May 6 and May 28, five autos had been held at Palma, at which 210 “Chuetas” (or Maranos) were condemned to imprisonment for life; and on May 6, 1691, 25 Chuetas were burned there.

Leave a reply to Royal Rosamond Press Cancel reply