Was the Heritage Foundation informed of Trump’s plan to alter the White House grounds?

Making the poor envious of the rich is a main theme of the Bible. Has Trump, the Republicans, and the Heritage Foundation read the Bible? How about the Constitution? Obamacare and the War on Poverty is all but dead. Did Trump’s father teach his son to look down on the poor and grab as much money as he can?

Below is the list of THE VERY RICH who contributed a fraction of their wealth to the grand ballroom. Comcast is going to have many people cancel their subscription when they go over the edge with the taking away of food stamps and Medicaid. Is this why Trump demands $250,000,000 million from the department of Justice, to pay for the losses of his rich pals? Trump keeps eluding to his belief that white men are better at making money, that black men, and Obama did not get the backing of the very wealthy.

John Fremont wanted to be President. If he could rise from the dead and behold the Obama’s dancing on Inauguration Day, he would be in heaven. Fremont Emancipated the slaves in Missouri. With the destruction of the West wing, the Republican Party – is dead!

John Presco

The Heritage Foundation is a right-wing think tank in Washington, D.C., founded in 1973, that promotes conservative public policies based on free enterprise, limited government, and individual freedom. It is a non-profit organization with a public policy mission, led by President Kevin Roberts, that conducts research and advocates for policies through its own staff and sister organization, Heritage Action. The organization also offers internships, educational programs, and is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, meaning it is tax-exempt.

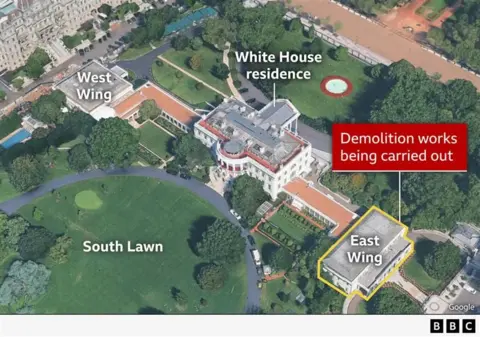

Trump says ‘existing structure’ of White House East Wing to be torn down

2:12Is Trump allowed to demolish part of the White House to build a ballroom?

US President Donald Trump has said the “existing structure” of the White House East Wing must be torn down in order to construct a new $250m (£186m) ballroom.

Crews began demolishing parts of the structure on Monday, and two administration officials earlier told the BBC’s US partner CBS that it will be completely torn down by the weekend.

It marks a significant expansion of the construction project announced over the summer. Trump previously said his ballroom addition would not “interfere with the current building”.

He rejected accusations he had not been transparent over the extent of the works, telling reporters on Wednesday: “I think we’ve been more transparent than anyone’s ever been.”

But criticism from opposition politicians has intensified as the scale of the works comes into focus. Democratic members of the US House of Representatives have now written to the president, raising their own transparency concerns and requesting a range of documents that relate to the demolition.

Conservationists have also suggested the project should have faced more scrutiny at the outset.

The White House is considered a special building that is exempt from the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which would ordinarily require public reviews of projects in which historic buildings are impacted.

However, Prof Priya Jain, the chair of a heritage preservation committee at the Society of Architectural Historians, said she “would be surprised if that process was not followed at the White House in the past”.

“That process is so well established, and is followed on thousands of buildings, and would have been best practice,” Prof Jain explained to the BBC.

- Trump says White House renovation is ‘music to my ears’ as criticism mounts

- Who is paying for Trump’s White House ballroom?

The White House has served as the historic home of the US president for two centuries. The East Wing was constructed in 1902 and was last modified in 1942.

It is a section of the White House that holds offices for the first lady and other staff, as well as meetings and special events.

Trump said the building had gone through several changes over the years and was “very, very much changed from what it was originally”.

He added that was “never thought of as being much” and that the changes have been wanted “for at least 150 years”.

The construction was being fully funded by Trump and “some friends of mine – donors”. The military was also involved, he added.

The US president announced construction had begun in a social media post on Monday, saying “ground has been broken” on the “much-needed” ballroom space.

He said that the East Wing was “completely separate” from the White House, although it is attached to the main structure.

The Trump administration officials told CBS it was always the case that the East Wing would have to be modernised to enhance security and technology, but that during the planning process, it became apparent that the best option would be to demolish the entirety of the East Wing.

0:37Watch as parts of White House East Wing torn down

Trump’s comments came after the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a Washington non-profit organisation that protects historic US sites, wrote a letter to White House officials saying it was “deeply concerned” by the project.

The trust asked Trump to pause demolition work, arguing that the White House was a national historic landmark and that officials needed to hold a public review process of the plan for the ballroom.

Some Democrats have been critical of the renovation, including Hilary Clinton, who ran against Trump for the US presidency in 2016.

In a post on X, she wrote that the White House was not Trump’s house, and “he’s destroying it”.

Additional reporting by Bernd Debusmann Jr

- Altria Group, Inc.

- Amazon

- Apple

- Booz Allen Hamilton

- Caterpillar, Inc.

- Coinbase

- Comcast Corporation

- J. Pepe and Emilia Fanjul

- Hard Rock International

- HP Inc.

- Lockheed Martin

- Meta Platforms

- Micron Technology

- Microsoft

- NextEra Energy, Inc.

- Palantir Technologies Inc.

- Ripple

- Reynolds American

- T-Mobile

- Tether America

- Union Pacific Railroad

- Adelson Family Foundation

- Stefan E. Brodie

- Betty Wold Johnson Foundation

- Charles and Marissa Cascarilla

- Edward and Shari Glazer

- Harold Hamm

- Benjamin Leon Jr.

- The Lutnick Family

- The Laura & Isaac Perlmutter Foundation

- Stephen A. Schwarzman

- Konstantin Sokolov

- Kelly Loeffler and Jeff Sprecher

- Paolo Tiramani

- Cameron Winklevoss

- Tyler Winklevoss

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

Most Popular

- CultureMatilda Djerf Is Still HereBy Stephanie McNeal

- EntertainmentAlexandra Grant and Keanu Reeves Clear Up Recent Rumors With a ‘Real’ KissBy Glamour

- BeautyDakota Johnson Just Gave Milk Bath Nails a Fresh Fall UpdateBy Grace McCarty

Advertisement

The Frémont Emancipation was part of a military proclamation issued by Major General John C. Frémont (1813–1890) on August 30, 1861, in St. Louis, Missouri during the early months of the American Civil War. The proclamation placed the state of Missouri under martial law and decreed that all property of those bearing arms in rebellion would be confiscated, including slaves, and that confiscated slaves would subsequently be declared free. It also imposed capital punishment for those in rebellion against the federal government.

Frémont, a career army officer, frontiersman and politician, was in command of the military Department of the West from July 1861 to October 1861. Although Frémont claimed his proclamation was intended only as a means of deterring secessionists in Missouri, his policy had national repercussions, potentially setting a highly controversial precedent that the Civil War would be a war of liberation.[1]

For President Abraham Lincoln the proclamation created a difficult situation, as he tried to balance the agendas of Radical Republicans who favored abolition and slave-holding Unionists in the American border states whose support was essential in keeping the states of Missouri, Kentucky and Maryland in the Union.[2]

Nationwide reaction to the proclamation was mixed. Abolitionists enthusiastically supported the measure while conservatives demanded Frémont’s removal.[3] Seeking to reverse Frémont’s actions and maintain political balance, Lincoln eventually ordered Frémont to rescind the edict on September 11, 1861.[4] Lincoln then sent various government officials to Missouri to build a case for Frémont’s removal founded on Frémont’s alleged incompetence rather than his abolitionist views.[5] On these grounds, Lincoln sent an order on October 22, 1861, removing Frémont from command of the Department of the West.[6] Although Lincoln opposed Frémont’s method of emancipation, the episode had a significant impact on Lincoln, shaping his opinions on the appropriate steps towards emancipation and eventually leading, sixteen months later, to Lincoln’s own Emancipation Proclamation.[7]

Background

Frémont

Main article: John C. Frémont

Born in Savannah, Georgia in 1813, John Charles Frémont would become one of the nation’s leading antislavery politicians in the 1850s.[3] Frémont was granted a second lieutenant’s commission in the U.S. Army’s Bureau of Topographical Engineers in 1838, primarily through the support of Secretary of War Joel Poinsett. As a young army officer, Frémont took part in several exploratory expeditions of the American West in the 1840s.[3] For his success in mapping a route across the Rocky Mountains to then Mexican California via the Oregon Trail, Frémont earned the nickname, “the Pathfinder” and attained the status of a national hero.[3] During the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), Major Frémont took command of the Californian revolt of American settlers against Mexico and was appointed military governor of California in 1847. Frémont’s independent actions ran at cross-purposes with the senior U.S. Army officer in California during the Mexican War—Stephen Watts Kearny. Frémont was arrested, brought to Washington, D.C. for a court-martial and resigned from the Army in 1848. Returning to the Pacific coast, Frémont became one of the first senators from California when it was granted statehood in 1850. In 1856, Frémont became the first Presidential candidate of the new Republican Party which established a platform advocating the limitation of slavery to those states in which it already existed.[3] Frémont won 33 percent of the popular vote, but lost to Democratic Party candidate James Buchanan.[8]

At the onset of the Civil War in April 1861, Frémont sought to resume his service in the Regular Army and was commissioned major general, becoming the third highest ranking general in the U.S. Army (according to date of appointment), just behind Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan.[9] Frémont was placed in command of the Department of the West which included all states and territories between the Mississippi River and the Rockies as well as the state of Illinois and the western part of Kentucky. The department was headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. Frémont arrived there and assumed command on July 25, 1861.[10] His chief task was to establish control within the state of Missouri.[11]

Missouri

Main article: Missouri in the American Civil War

At the commencement of the Civil War, Missouri was a deeply divided state. Missouri had chosen to remain in the Union, and initially maintained a policy of neutrality towards both the Union and the Confederacy. However, Missouri was also a state in which slavery was still legal, a factor which generated sympathy for the Confederacy and secession. The governor of Missouri at the start of the war, Claiborne Jackson, was in favor of secession and attempted to use the Missouri State Militia to resist the build-up of Union forces in his state.[12]

Before Frémont, two generals had previously served as head of the Department of the West during the first four months of the war. Brigadier General William S. Harney had taken a diplomatic approach in Missouri, attempting to respect Missouri’s neutrality through the Price-Harney Truce, negotiated with Sterling Price, commander of the Missouri State Militia.[13] The truce was unacceptable to many Unionists and particularly to President Lincoln, as continued neutrality in Missouri would result in the state’s refusal to supply men for the Union army. Harney was removed on May 30 and replaced with the hard-line Radical Republican Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon.[14] Earlier, while still a subordinate of Harney’s, Lyon had raised tensions in Missouri to a fever-pitch by acting independently and capturing a portion of the Missouri State Militia during the Camp Jackson Affair on May 10, 1861. Although the maneuver eliminated a threat to the St. Louis Arsenal, it also caused a riot in St. Louis.[15] As commander of the Department of the West, Lyon met with Gov. Jackson and informed him that, “rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my government in any matter…I would see you…and every man and woman and child in the State dead and buried.”[16] After this, open warfare commenced between pro-Confederate militia and Union forces in Missouri. Gov. Jackson fled St. Louis, and the Missouri State Militia was re-organized to become the Missouri State Guard—a pro-secession force under the command of Sterling Price and Governor-in-Exile Jackson.

By the time Frémont took command in St. Louis on July 25, 1861, Union forces under Lyon had fought in several engagements against the Missouri State Guard. On August 10, a combined force of Missouri State Guard, Confederate States Army, and Arkansas Militia, consisting of about 11,000 troops, closed in on Lyon’s Union force numbering approximately 5,000 near Springfield, Missouri.[17] During the ensuing Battle of Wilson’s Creek, Lyon was killed and the federal force routed. Pro-secession sentiment surged throughout Missouri following the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. Estimates by Union army officials placed the number of armed secessionists in Missouri at roughly 60,000.[18] Alarmed by the increasing turbulence, Frémont declared martial law in the state of Missouri on August 30, 1861.[19]

Proclamation and reaction

Just before dawn on August 30, Frémont finished penning his proclamation of martial law and read it to his wife and a trusted advisor, Edward Davis of Philadelphia. Davis warned that officials in Washington would never stand for such a sweeping edict. Frémont responded that he had been given full power to put down secession in Missouri and that, as a war measure, the proclamation was entirely warranted.[20]

The most controversial passage of the proclamation, and the one with the greatest political consequences, was the following:[3]

All persons who shall be taken with arms in their hands within these lines shall be tried by court-martial, and, if found guilty, will be shot. The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, and who shall be directly proven to have taken active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use; and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free.[21]

The two measures described within this passage threatened to alienate Unionists in each of the border states. Drawing a line from Cape Girardeau, Missouri to Leavenworth, Kansas, Frémont declared capital punishment would be administered to any secessionists bearing arms north of that line.[19] Further, the proclamation freed the slaves of any secessionists who took up arms against the government. Frémont issued his proclamation without consulting any authority in Missouri or Washington.[3]

The proclamation freed very few slaves. First, and most prominently, two slaves belonging to an aide of the former Gov. Jackson, Frank Lewis and Hiram Reed, were given their manumission papers. This act received significant coverage by the St. Louis press.[19] Frémont then issued papers to 21 other slaves.[22] However, the greatest significance of the proclamation came in the form of political ramifications. The proclamation set a political precedent, over which there was tremendous disagreement, whether a Union general had any basis of authority to emancipate slaves.[23] This threatened to tip the delicate political balance in border states. Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland all might have been pushed towards secession if such a precedent had been backed by the federal government at the beginning of the war.[24]

Unionists in Missouri were divided in their reaction. Radical Republicans, who favored abolition, were overjoyed. This included much of the St. Louis press.[3] Frémont surrounded himself with men of this faction, and several Radical Republican politicians had come to St. Louis with him as aides and advisors. These included Illinois Congressman Owen Lovejoy (brother of the antislavery journalist Elijah Lovejoy who had been murdered in 1837 by an anti-abolitionist mob), Ohio Congressman John A. Gurley and Indiana Congressman John P.C. Shanks. All ardent abolitionists, these men encouraged and influenced Frémont’s proclamation.[25] More moderate Unionists were troubled by Frémont’s proclamation and pro-slavery conservatives were outraged.[19] Most important, among the moderates in Missouri alienated by Frémont’s proclamation was the new governor of Missouri, Hamilton Rowan Gamble, whose authority Frémont had now superseded by declaring martial law. Feeling that Frémont had greatly overstepped his authority, Gamble began to work for Frémont’s removal.[3] In neighboring Kentucky, there was widespread outrage. Although the proclamation pertained only to the state of Missouri, Kentuckians feared that a similar edict might be applied by Frémont to their state. Most slaves in Kentucky belonged to Unionists and threatening to free them could have pushed the state into the Confederacy.[2]

Lincoln’s reaction and Frémont’s removal

President Lincoln learned of Frémont’s proclamation by reading it in the newspaper.[23] Disturbed by Frémont’s actions, Lincoln felt that emancipation was “not within the range of military law or necessity” and that such powers rested only with the elected federal government.[26] Lincoln also recognized the monumental political problem that such an edict posed to his efforts to keep the border states in the Union. He was particularly worried about reports he heard of the furor in Kentucky over the edict, writing, “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game.”[27] According to Lincoln in a letter to a supporter of Frémont, a unit of Kentucky militia fighting for the Union, upon hearing of Frémont’s proclamation, threw down their weapons and disbanded.[27] Lincoln determined the proclamation could not be allowed to remain in force. However, to override the edict or to directly order Frémont to strike out or modify the paragraph had its own political dangers—such an act would outrage abolitionists throughout the North. Sensitive to the political pitfalls on all sides, Lincoln wrote to Frémont, “Allow me to therefore ask, that you will, as of your own motion, modify that paragraph…”[24]

Frémont wrote a reply to Lincoln’s request on September 8, 1861, and sent it to Washington in the hands of his wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, who met with the President in the White House on September 10. In the letter, Frémont stated that he knew the situation in Missouri better than the President and that he would not rescind the proclamation unless directly ordered. Angered, Lincoln wrote Frémont the next day, directly ordering him to modify the emancipation clause to conform with existing federal law—that only slaves themselves acting in armed rebellion could be confiscated and freed.[4]

Lincoln could not allow Frémont’s insubordination to go unpunished. However, his dilemma again lay in politics. Removal of Frémont over the emancipation issue would infuriate radicals in Congress. Lincoln determined that if Frémont were to be removed, it would have to be for matters unrelated to the proclamation. He therefore sent Postmaster General Montgomery Blair and Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs to Missouri to evaluate Frémont’s management of his department.[5] On his return, Blair reported that a tremendous state of disorganization existed in Missouri and Frémont “seemed stupified…and is doing absolutely nothing.”[6] When Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas made his own inspection and reported to Lincoln that Frémont was, “wholly incompetent,” Lincoln decided to leak Thomas’s report to the press.[28] Amidst the resulting public outrage against Frémont, Lincoln sent an order on October 22, 1861, removing him from command of the Department of the West.[6]

Aftermath

For Frémont, the personal repercussions of his proclamation were disastrous. His removal from command of the Western Department did irreparable damage to his reputation.[3] Giving Frémont a second chance, Lincoln approved his appointment to command the strategically important Mountain Department, overseeing the mountainous region surrounding the Virginia and Kentucky border. Frémont’s forces were badly defeated, however, in the Battle of Cross Keys in Virginia on June 8, 1862.[3] He eventually resigned from frustration at being passed over when Lincoln appointed Maj. Gen. John Pope to command of the Army of Virginia, and spent the rest of the war awaiting a new appointment which never came.[3]

For Lincoln, the immediate effects of Frémont’s removal resulted in the furor the president had anticipated from northern abolitionists. Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew, a Radical Republican and abolitionist, wrote that Lincoln’s actions had a “chilling influence” on the antislavery movement.[29] The outrage was only a short-term effect, however, and soon subsided.[29]

The most significant long-term consequence of the Frémont Emancipation was the effect it had on Lincoln’s perceptions of emancipation and, specifically, how it should be accomplished. As historian Allen Guelzo describes, Lincoln became determined, after Frémont’s failed proclamation, that emancipation could not be a matter of martial law or some other temporary measure that would later be challenged in courts. To ensure its permanence, Lincoln felt, emancipation would have to be put into effect by the federal government in a manner that was incontrovertibly constitutional.[30] Equally important, the timing of emancipation would need to be orchestrated carefully, so as not to interfere with the war effort. Although in 1861, Lincoln had not yet espoused the idea of immediate emancipation and still hoped to work with state governments to accomplish gradual and perhaps even a compensated emancipation, the Frémont incident solidified Lincoln’s belief that emancipation was the President’s responsibility and could not be accomplished by scattered decrees from Union generals. This realization was one of several factors that led to Lincoln’s own Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862.[7]

Leave a comment