What does INRI mean, and how does it apply to modern Christians? T

Evangelicals and Christian Nationalists claim Jesus was God, who came amongst mortals to be crucified by them, and thus dying for everyone’s sins so they will know eternal life. Why then is God in CONTENTION to be….

THE KING OF THE JEWS?

How about….

KING OF THE JEBUSITES?

Now that there exist a JESUS 2025 PLAN FOR AMERICA, it is time we blow away the smoke, and smash the mirrors. If it is the aim of the Republican Party of Jesus to force all Americans to believe in Jesus, and the American King – Donald Trump – can we at least know

WHAT A NAZARENE IS?

We are talking about GOF’S BRANDING! Quite frankly – it sucks! Why all this guesswork about Jesus and his mission? There was no slaughter of the innocents. I suspect Herod ordered a COUNTING of children and infants which put them in line for the wrath of…..

THE ANGEL OF THE THRESHING FLOOR

The Greeks and Romans had no qualms about advertising their immortal Gods…..OF OLYMPUS! What’s so sepcial about the city of Nazareth that is not named in the Old Testament. Why not….

JESUS THE BRINGER OF ETERNAL LIFE?

Who cares where he lived if this is – THE PRODECT?

“You too can live as long as any Roman God. Go tell your slave master you are a immortal – and way better than he is!”

“Sign me up!”

I believe Jesus was a NAZARITE like John the Baptist, who was filled with the Holy Spirit – WHILE IN HIS MOTHER’S WOMB!

WOW! This is what I call BRANDING!

John ‘The Nazarite’

Others point to a passage in the Book of Judges which refers to Samson as a Nazirite, a word that is just one letter off from Nazarene in Greek.[7] It is also possible that Nazorean signs Jesus as a ruler.[8]

Another theory holds that the Greek form Ναζαρά (Nazará), used in the Gospel of Matthew and Gospel of Luke, may derive from an earlier Aramaic form of the name, or from another Semitic language form.[14] If there were a tsade (צ) in the original Semitic form, as in the later Hebrew forms, it would normally have been transcribed in Greek with a sigma (σ) instead of a zeta (ζ).[15] This has led some scholars to question whether “Nazareth” and its cognates in the New Testament actually refer to the settlement known traditionally as Nazareth in Lower Galilee.[16] Such linguistic discrepancies may be explained, however, by “a peculiarity of the ‘Palestinian’ Aramaic dialect wherein a sade (ṣ) between two voiced (sonant) consonants tended to be partially assimilated by taking on a zayin (z) sound”.[15]

Another theory holds that the Greek form Ναζαρά (Nazará), used in the Gospel of Matthew and Gospel of Luke, may derive from an earlier Aramaic form of the name, or from another Semitic language form.[14] If there were a tsade (צ) in the original Semitic form, as in the later Hebrew forms, it would normally have been transcribed in Greek with a sigma (σ) instead of a zeta (ζ).[15] This has led some scholars to question whether “Nazareth” and its cognates in the New Testament actually refer to the settlement known traditionally as Nazareth in Lower Galilee.[16] Such linguistic discrepancies may be explained, however, by “a peculiarity of the ‘Palestinian’ Aramaic dialect wherein a sade (ṣ) between two voiced (sonant) consonants tended to be partially assimilated by taking on a zayin (z) sound”.[15]

In the New Testament, Jesus is referred to as the King of the Jews, both at the beginning of his life and at the end. In the Koine Hellenic of the New Testament, e.g., in John 19:3, this is written as Basileus ton Ioudaion (βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων).[1]

Both uses of the title lead to dramatic results in the New Testament accounts. In the account of the nativity of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, the Biblical Magi who come from the east call Jesus the “King of the Jews”, implying that he was the Messiah. This caused Herod the Great to order the Massacre of the Innocents. Towards the end of the accounts of all four canonical Gospels, in the narrative of the Passion of Jesus, the title “King of the Jews” leads to charges against Jesus that result in his crucifixion.[2][3]

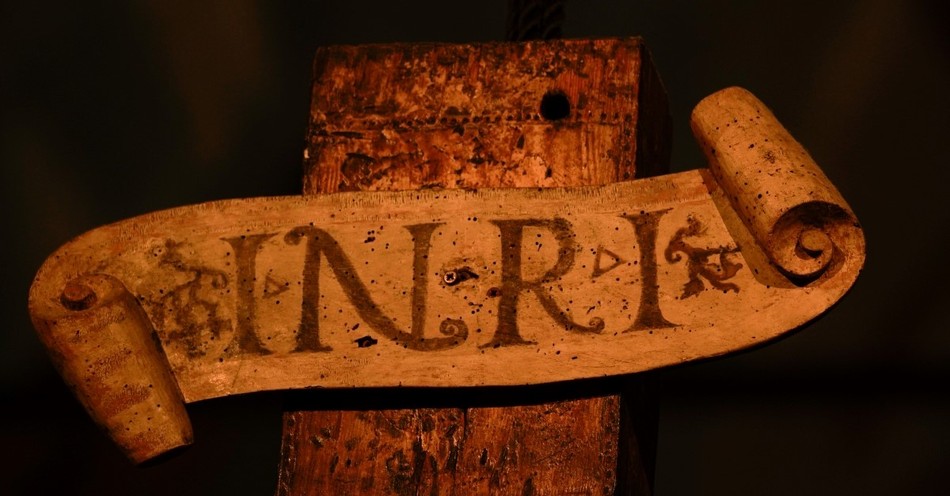

The initialism INRI (Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum) represents the Latin inscription (in John 19:19 and Matthew 27:37), which in English translates to “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews”, and John 19:20 states that this was written in three languages—Jewish tongue,[a] Latin, and Hellenic (ΙΝΒΙ = Ιησούς Ναζωραίος Βασιλεύς Ιουδαίων)—during the crucifixion of Jesus.

The title “King of the Jews” is only used in the New Testament by gentiles, namely by the Magi, Pontius Pilate, and the Roman soldiers. In contrast, the Jews in the New Testament use the title “King of Israel”[7][2] or the Hebrew word Messiah, which can also mean king.

Although the phrase “King of the Jews” is used in most English translations,[b] it has also been translated “King of the Judeans” (see Ioudaioi).[8]

In the nativity

Further information: Matthew 2:7 and Matthew 2:8

In the account of the nativity of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, the Biblical Magi go to King Herod in Jerusalem and (in Matthew 2:2) ask him: “Where is he that is born King of the Jews?”[9] Herod asks the “chief priests and teachers of the law”, who tell him in Bethlehem of Judea.

The question troubles Herod who considers the title his own, and in Matthew 2:7–8 he questions the Magi about the exact time of the Star of Bethlehem‘s appearance. Herod sends the Magi to Bethlehem, telling them to notify him when they find the child. After the Magi find Jesus and present their gifts, having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they returned to their country by a different way.

An angel appears to Joseph in a dream and warns him to take Jesus and Mary into Egypt (Matthew 2:13). When Herod realizes he has been outwitted by the Magi he gives orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who are two years old and under. (Matthew 2:16)

In the Passion narratives

In the accounts of the Passion of Jesus, the title King of the Jews is used on three occasions. In the first such episode, all four Gospels state that the title was used for Jesus when he was interviewed by Pilate and that his crucifixion was based on that charge, as in Matthew 27:11, Mark 15:2, Luke 23:3 and John 18:33.[10]

The use of the terms king and kingdom and the role of the Jews in using the term king to accuse Jesus are central to the discussion between Jesus and Pilate. In Matthew 27:11, Mark 15:2, and Luke 23:3 Jesus responds to Pilate, “you have said so” when asked if Jesus is the King of the Jews and says nothing further. This answer is traditionally interpreted as an affirmative.[11][12][13] Some scholars describe it as ambiguous and enigmatic.[11][14] Other scholars say it was calculated not to anger Pilate while allowing the gospel reader to understand that the answer is affirmative.[15][16] In John 18:34, he hints that the king accusation did not originate with Pilate but with “others” and, in John 18:36, he states: “My kingdom is not of this world”. However, Jesus does not directly deny being the King of the Jews.[17][18]

In the New Testament, Pilate writes “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews” as a sign to be affixed to the cross of Jesus. John 19:21 states that the Jews told Pilate: “Do not write King of the Jews” but instead write that Jesus had merely claimed that title, but Pilate wrote it anyway.[19] Pilate’s response to the protest is recorded by John: “What I have written, I have written.”

After the trial by Pilate and after the flagellation of Christ episode, the soldiers mock Jesus as the King of Jews by putting a purple robe (that signifies royal status) on him, place a Crown of Thorns on his head, and beat and mistreat him in Matthew 27:29–30, Mark 15:17–19 and John 19:2–3.[20]

The continued reliance on the use of the term king by the Judeans to press charges against Jesus is a key element of the final decision to crucify him.[3] In John 19:12 Pilate seeks to release Jesus, but the Jews object, saying: “If thou release this man, thou art not Caesar’s friend: every one that maketh himself a king speaketh against Caesar”, bringing the power of Caesar to the forefront of the discussion.[3] In John 19:12, the Jews then cry out: “Crucify him! … We have no king but Caesar.”

The use of the term “King of the Jews” by the early Church after the death of Jesus was thus not without risk, for this term could have opened them to prosecution as followers of Jesus, who was accused of possible rebellion against Rome.[3]

The final use of the title only appears in Luke 23:36–37. Here, after Jesus has carried the cross to Calvary and has been nailed to the cross, the soldiers look up on him on the cross, mock him, offer him vinegar and say: “If thou art the King of the Jews, save thyself.” In the parallel account in Matthew 27:42, the Jewish priests mock Jesus as “King of Israel”, saying: “He is the King of Israel; let him now come down from the cross, and we will believe in him.”

King of the Jews vs King of Israel

In the New Testament, the “King of the Jews” title is used only by the gentiles, by the Magi, Pontius Pilate, and Roman soldiers. In contrast, the Jews in the New Testament prefer the designation “King of Israel” as used reverentially by Jesus’ Jewish followers in John 1:49 and John 12:13, and mockingly by the Jewish leaders in Matthew 27:42 and Mark 15:32. From Pilate’s perspective, it is the term “King” (regardless of Jews or Israel) that is sensitive, for it implies possible rebellion against the Roman Empire.[2]

In the Gospel of Mark the distinction between King of the Jews and King of Israel is made consciously, setting apart the two uses of the term by the Jews and the gentiles.[7]

INRI and ΙΝΒΙ

“INRI” redirects here. For other uses, see INRI (disambiguation).

The initialism INRI represents the Latin inscription Iesvs Nazarenvs Rex Ivdæorvm (Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum), which in English translates to “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews” (John 19:19).[21] John 19:20 states that this was written in three languages – Hebrew,[a] Latin, and Greek – and was put on the cross of Jesus. The Greek version of the initialism reads ΙΝΒΙ, representing Ἰησοῦς ὁ Ναζωραῖος ὁ βασιλεύς τῶν Ἰουδαίων (Iēsoûs ho Nazōraîos ho basileús tôn Ioudaíōn).[22]

Devotional enthusiasm greeted the discovery by Pedro González de Mendoza in 1492 of what was acclaimed as the actual tablet, said to have been brought to Rome by Saint Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine.[23][24]

Western Christianity

In Western Christianity, most crucifixes and many depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus include a plaque or parchment placed above his head, called a titulus, or title, bearing only the Latin letters INRI, occasionally carved directly into the cross and usually just above the head of Jesus. The initialism INRI (as opposed to the full inscription) was in use by the 10th century (Gero Cross, Cologne, ca. 970).

Eastern Christianity

In Eastern Christianity, both the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Eastern Catholic particular churches sui iuris use the Greek letters ΙΝΒΙ, based on the Greek version of the inscription Ἰησοῦς ὁ Ναζωραῖος ὁ βασιλεύς τῶν Ἰουδαίων. Some representations change the title to “ΙΝΒΚ,” ὁ βασιλεύς τοῦ κόσμου (ho Basileùs toû kósmou, “The King of the World”), or to ὁ βασιλεύς τῆς Δόξης (ho Basileùs tês Dóxēs, “The King of Glory”),[22][25] not implying that this was really what was written but reflecting the tradition that icons depict the spiritual reality rather than the physical reality.

The Romanian Orthodox Church uses INRI, since abbreviation in Romanian is exactly the same as in Latin (Iisus Nazarineanul Regele Iudeilor).

Eastern Orthodox Churches that use Church Slavonic in their liturgy use ІНЦІ (INTsI, the equivalent of ΙΝΒΙ for Church Slavonic: І҆и҃съ назѡрѧни́нъ, цр҃ь і҆ꙋде́йскїй) or the abbreviation Царь Сла́вы (Tsar Slávy, “King of Glory”).

Versions in the gospels

| Matthew | Mark | Luke | John | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verse | Matthew 27:37 | Mark 15:26 | Luke 23:38 | John 19:19–20 |

| Greek Inscription | οὗτός ἐστιν Ἰησοῦς ὁ βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων | ὁ βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων | ὁ βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων οὗτος | Ἰησοῦς ὁ Ναζωραῖος ὁ βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων |

| Transliteration | hûtós estin Iēsûs ho basileùs tôn Iudaéōn | ho basileùs tôn Iudaéōn | ho basileùs tôn Iudaéōn hûtos | Iēsûs ho Nazōraêos ho basileùs tôn Iudaéōn |

| Vulgata Xystina-Clementina (Latin) | Hic est Iesus rex Iudæorum | Rex Iudæorum | Hic est rex Iudæorum | Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudæorum |

| English translation | This is Jesus, the King of the Jews | The King of the Jews | This is the King of the Jews | Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews |

| Languages | [none specified] | [none specified] | Hebrew, Latin, Greek[c] | Hebrew, Latin, Greek |

| Full verse in KJV | And set up over His head His accusation written, THIS IS JESUS THE KING OF THE JEWS | And the superscription of His accusation was written over, THE KING OF THE JEWS. | And a superscription also was written over Him in letters of Greek, and Latin, and Hebrew, THIS IS THE KING OF THE JEWS. | And Pilate wrote a title, and put it on the cross. And the writing was, JESUS OF NAZARETH THE KING OF THE JEWS. This title then read many of the Jews: for the place where Jesus was crucified was nigh to the city: and it was written in Hebrew, and Greek, and Latin. |

Other uses of INRI

See also: INRI (disambiguation)

In Spanish, the word inri denotes any insulting or mocking word or phrase; it is usually found in the fixed expression para más/mayor inri (literally “for more/greater insult”), which idiomatically means “to add insult to injury” or “to make matters worse”.[30] Its origin is sometimes made clearer by capitalisation para más INRI.

The initials INRI have been reinterpreted with other expansions (backronyms). In an 1825 book on Freemasonry, Marcello Reghellini de Schio alleged that Rosicrucians gave “INRI” alchemical meanings:[31]

- Latin Igne Natura Renovatur Integra (“by fire, nature renews itself”); other sources have Igne Natura Renovando Integrat

- Latin Igne Nitrum Roris Invenitur (“the nitre of dew is found by fire”)

- Hebrew ימים, נור, רוח, יבשת (Yammīm, Nūr, Rūaḥ, Yabešet, “water, fire, wind, earth” — the four elements)

Later writers have attributed these to Freemasonry, Hermeticism, or neo-paganism. Aleister Crowley‘s The Temple of Solomon the King includes a discussion of Augoeides, supposedly written by “Frater P.” of the A∴A∴:[32]For since Intra Nobis Regnum deI [footnote in original: I.N.R.I.], all things are in Ourself, and all Spiritual Experience is a more of less complete Revelation of Him [i.e. Augoeides].

Latin Intra Nobis Regnum deI literally means “Inside Us the Kingdom of god”.

Leopold Bloom, the nominally Catholic, ethnically Jewish protagonist of James Joyce‘s Ulysses, remembers his wife Molly Bloom interpreting INRI as “Iron Nails Ran In”.[33][34][35][36] The same meaning is given by a character in Ed McBain‘s 1975 novel Doors.[37] Most Ulysses translations preserve “INRI” and make a new misinterpretation, such as the French Il Nous Refait Innocents “he makes us innocent again”.[38]

Isopsephy

In isopsephy, the Greek term (βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἰουδαίων) receives a value of 3343 whose digits seem to correspond to a suggested date for the crucifixion of Jesus, (33, April, 3rd day).

Nazarene is a title used to describe people from the city of Nazareth in the New Testament (there is no mention of either Nazareth or Nazarene in the Old Testament), and is a title applied to Jesus, who, according to the New Testament, grew up in Nazareth,[1] a town in Galilee, located in ancient Judea. The word is used to translate two related terms that appear in the Greek New Testament: Nazarēnos (‘Nazarene’) and Nazōraios (‘Nazorean‘). The phrases traditionally rendered as “Jesus of Nazareth” can also be translated as “Jesus the Nazarene” or “Jesus the Nazorean”,[2] and the title Nazarene may have a religious significance instead of denoting a place of origin. Both Nazarene and Nazorean are irregular in Greek and the additional vowel in Nazorean complicates any derivation from Nazareth.[3]

The Gospel of Matthew explains that the title Nazarene is derived from the prophecy “He will be called a Nazorean”,[4] but this has no obvious Old Testament source. Some scholars argue that it refers to a passage in the Book of Isaiah,[5] with Nazarene a Greek reading of the Hebrew ne·tser (‘branch’), understood as a messianic title.[6] Others point to a passage in the Book of Judges which refers to Samson as a Nazirite, a word that is just one letter off from Nazarene in Greek.[7] It is also possible that Nazorean signs Jesus as a ruler.[8]

The Greek New Testament uses Nazarene six times (Mark, Luke), while Nazorean is used 13 times (Matthew, Mark in some manuscripts, Luke, John, Acts). In the Book of Acts, Nazorean is used to refer to a follower of Jesus, i.e. a Christian, rather than an inhabitant of a town.[9] Notzrim is the modern Hebrew word for Christians (No·tsri, נוֹצְרִי) and one of two words commonly used to mean ‘Christian’ in Syriac (Nasrani) and Arabic (Naṣrānī, نصراني).

Etymology

Nazarene is anglicized from Greek Nazarēnos (Ναζαρηνός), a word applied to Jesus in the New Testament.[10] Several Hebrew words have been suggested as roots:[11]

Nazareth

The traditional view is that this word’s derived from the Hebrew word for Nazareth (Nazara) that was used in ancient times.[12] Nazareth, in turn, may be derived from either na·tsar, נָצַר, meaning ‘to watch’,[13] or from ne·tser, נֵ֫צֶר, meaning ‘branch’.[14]

The common Greek structure Iesous o Nazoraios (Ἰησοῦς ὁ Ναζωραῖος) ‘Jesus the Nazarene/of Nazareth’ is traditionally considered as one of several geographical names in the New Testament such as Loukios o Kurenaios (Λούκιος ὁ Κυρηναῖος) ‘Lucius the Cyrenian/Lucius of Cyrene‘, Trofimos o Efesios (‘Trophimus the Ephesian’, Τρόφιμος ὁ Ἐφέσιος), Maria Magdalene (‘Mary the woman of Magdala’), Saulos Tarseus (‘Saul the Tarsian’), or many classical examples such as Athenagoras the Athenian (Ἀθηναγόρας ὁ Ἀθηναῖος).

The Greek phrase usually translated as Jesus of Nazareth (iēsous o nazōraios) can be compared with three other places in the New Testament where the construction of Nazareth is used:

How God anointed Jesus of Nazareth (ho apo Nazaret, ὁ ἀπὸ Ναζαρέτ) with the Holy Ghost and with power: who went about doing good, and healing all that were oppressed of the devil; for God was with him. Acts 10:38 KJV 1611

Jesus is also referred to as “from Nazareth of Galilee”:

And the crowds said, “This is the prophet Jesus, from Nazareth of Galilee.” (ho apo Nazaret tes Galilaias, ὁ ἀπὸ Ναζαρὲτ τῆς Γαλιλαίας) Matthew 21:11

Similar is found in John 1:45–46:

Philip findeth Nathanael, and saith unto him, We have found him, of whom Moses in the law, and the prophets, did write, Jesus, the son of Joseph, he from Nazareth (τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ Ἰωσὴφ τὸν ἀπὸ Ναζαρέτ; Nominative case: ho uios tou Iosef ho apo Nazaret).

And Nathanael said unto him, Can there any good thing come out of Nazareth (ek Nazaret ἐκ Ναζαρὲτ)? Philip saith unto him, Come and see.

Some consider Jesus the Nazarene more common in the Greek.[15] The name “of Nazareth” is not used of anyone else, and outside the New Testament there is no 1st-century reference to Nazareth.

Nazareth and Nazarene are complementary only in Greek, where they possess the “z”, or voiced alveolar fricative. In Semitic languages, Nazarene and its cognates Nazareth, Nazara, and Nazorean/Nazaraean possess the voiceless alveolar fricative corresponding to the “s” or “ts” sound. Voiced and voiceless sounds follow separate linguistic pathways. The Greek forms referring to Nazareth should therefore be Nasarene, Nasoraios, and Nasareth.[citation needed] The additional vowel (ω) in Nazorean makes this variation more difficult to derive, although a weak Aramaic vowel in Nazareth has been suggested as a possible source.[3]

Ne·tzer

- ne·tser (נֵ֫צֶר, n-ts-r), pronounced nay’·tser, meaning ‘branch’, ‘flower’, or ‘offshoot’. Derived from na·tsar. (See below.)[16][page needed]

Jerome (c. 347 – 420) linked Nazarene to a verse in the Book of Isaiah, claiming that Nazarene was the Hebrew reading of a word scholars read as ne·tzer (‘branch’).[17] The text from Isaiah is:

There shall come forth a Rod from the stem of Jesse, And a Branch shall grow out of his roots. ve·ya·tza cho·ter mig·ge·za yi·shai ve·ne·tzer mi·sha·ra·shav yif·reh.[5]

In ancient Hebrew texts, vowels were not indicated, so a wider variety of readings was possible in Jerome’s time. Here branch/Nazarene is metaphorically “descendant” (of Jesse, father of King David). Eusebius, a 4th-century Christian polemicist, also argued that Isaiah was the source of Nazarene. This prophecy by Isaiah was extremely popular in New Testament times and is also referred to in Romans and Revelation.[18]

Ancient usage

The term Nazarene (Nazorean or Nazaraean) has been referred to in the Jewish Gospels, particularly the Hebrew Gospel, the Gospel of the Nazarenes and the Gospel of Matthew. It is also referred to in the Gospel of Mark.[19]

Matthew

Matthew consistently uses the variant Nazorean. A link between Nazorean and Nazareth is found in Matthew:

And after being warned in a dream, he went away to the district of Galilee. There he made his home in a town called Nazareth, so that what had been spoken through the prophets might be fulfilled, “He will be called a Nazorean.”[20]

The passage presents difficulties; no prophecy such as “He shall be called a Nazorean” is known in Jewish scripture, and Nazorean is a new term, appearing here for the first time in association with Nazareth and, indeed, for the first time anywhere.

Matthew’s prophecy is often linked to Isaiah’s.[5] Although only Isaiah’s prophecy gives ‘branch’ as ne·tser, there are four other messianic prophecies where the word for branch is given as tze·mach.[21] Matthew’s phrase “spoken through the prophets” may suggest that these passages are being referred to collectively.[6] In contrast, the phrase “through the prophet”, used a few verses above the Nazorean prophecy,[22] refers to a specific Old Testament passage.[23]

An alternative view suggests that a passage in the Book of Judges which refers to Samson as a Nazirite is the source for Matthew’s prophecy. Nazirite is only one letter off from Nazorean in Greek.[7] But the characterization of Jesus in the New Testament is not that of a typical Nazirite, and it is doubtful that Matthew intended a comparison between Jesus and the amoral Samson.[7] But Nazorean can be a transliteration of the NZR, which also means ‘ruler’ (s. Gen 49,26), referring to Jesus as the new ruler of Israel.[24]

Mark

See also: Mark 1

The Gospel of Mark, considered the oldest gospel, consistently uses Nazarene, while scripture written later generally uses Nazorean. This suggests that the form more closely tied to Nazareth came first. Another possibility is that Mark used this form because the more explicitly messianic form was still controversial when he was writing. Before he was baptized, Mark refers to Jesus as “from Nazareth of Galilee”,[25] whereas afterwards he is “the Nazarene”.[26] In a similar fashion, second century messianic claimant Simon bar Kokhba (Aramaic for ‘Simon, son of a star’), changed his name from Simon bar Kosiba to add a reference to the Star Prophecy.[27]

Patristic works

After Tertullus (Acts 24:5), the second reference to Nazarenes (plural) comes from Tertullian (208), the third reference from Eusebius (before 324), then extensive references in Epiphanius of Salamis (375) and Jerome (circa 390).

Epiphanius additionally is the first and only source to write of another group with a similar name, the “Nasarenes” of Gilead and Bashan in Trans-Jordan (Greek: Nasaraioi Panarion 18). Epiphanius clearly distinguishes this group from the Christian Nazarenes as a separate and different “pre-Christian” Jewish sect.[28] Epiphanius’ explanation is dismissed as a confusion by some scholars (Schoeps 1911, Schaeder 1942, Gaertner 1957), or a misidentification (Bugge). Other scholars have seen some truth in Epiphanius’ explanation and variously identified such a group with the Mandeans, Samaritans, or Rechabites.[29]

Gnostic works

The Gospel of Philip, a third-century Gnostic work,[30] claims that the word Nazarene signifies ‘the truth’:

“Jesus” is a hidden name, “Christ” is a revealed name. For this reason “Jesus” is not particular to any language; rather he is always called by the name “Jesus”. While as for “Christ”, in Syriac it is “Messiah”, in Greek it is “Christ”. Certainly all the others have it according to their own language. “The Nazarene” is he who reveals what is hidden. Christ has everything in himself, whether man, or angel, or mystery, and the Father….[31] The apostles who were before us had these names for him: “Jesus, the Nazorean, Messiah”, that is, “Jesus, the Nazorean, the Christ”. The last name is “Christ”, the first is “Jesus”, that in the middle is “the Nazarene”. “Messiah” has two meanings, both “the Christ” and “the measured”. “Jesus” in Hebrew is “the redemption”. “Nazara” is “the Truth”. “The Nazarene” then, is “the Truth”. “Christ” [unreadable] has been measured. “The Nazarene” and “Jesus” are they who have been measured.[32]

Historicity

Although the historian Flavius Josephus (AD 37 – c. 100) mentions 45 towns in Galilee, he never mentions Nazareth. But Josephus also writes that Galilee had 219 villages in all,[33] so it is clear that most village names have gone unrecorded in surviving literature. Nazareth was overshadowed by nearby Japhia in his time, so Josephus might not have thought of it as a separate town.[34] The earliest known reference to Nazareth outside the New Testament and as a contemporary town is by Sextus Julius Africanus, who wrote around AD 200.[35] Writers who question the association of Nazareth with the life of Jesus suggest that Nazorean was originally a religious title and was later reinterpreted as referring to a town.[36]

Variants

The numbers in parentheses are from Strong’s Concordance.

Nazarene (3479)

- Nazarēne (Ναζαρηνέ) Mark 1:24, Luke 4:34

- Nazarēnon (Ναζαρηνὸν) Mark 16:6

- Nazarēnos (Ναζαρηνός) Mark 10:47

- Nazarēnou (Ναζαρηνοῦ) Mark 14:67, Luke 24:19

Nazorean (3480)

- Nazōraios (Ναζωραῖος) Matthew 2:23, Luke 18:37, John 19:19 Acts 6:14, Acts 22:8

- Nazōraiou (Ναζωραίου) Matthew 26:71, Acts 3:6, Acts 4:10, Acts 26:9

- Nazōraiōn (Ναζωραίων) Acts 24:5

- Nazōraion (Ναζωραῖον) John 18:5, John 18:7, Acts 2:22

Nazareth (3478)

- Nazareth (Ναζαρέθ) Matthew 21:11, Luke 1:26, Luke 2:4, Luke 2:39, Luke 2:51, Acts 10:38

- Nazara (Ναζαρά) Matthew 4:13, Luke 4:16

- Nazaret (Ναζαρέτ) Mark 1:9, Matthew 2:23, John 1:45, John 1:46

Look up Nazarene in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Nazarenes – a term for the early Christians

The first confirmed use of Nazarenes (in Greek Nazoraioi) occurs from Tertullus before Antonius Felix.[37] One such as Tertullus who did not acknowledge Iesous ho Nazoraios (‘Jesus of Nazareth’) as Iesous ho Christos (‘Jesus the Messiah’) would not call Paul’s sect Christianoi (‘followers of the Messiah’).[38]

Nazarenes for Christians in Greek

In Acts, Paul the Apostle is called “a ringleader of the sect of the Nazoreans”,[9] thus identifying Nazorean with Christian. Although both Christianios (by Gentiles) and Nazarenes (by Jews) appear to have been current in the 1st century, and both are recorded in the New Testament, the Gentile name Christian appears to have won out against Nazarene in usage among Christians themselves after the 1st century. Around 331 Eusebius records that from the name Nazareth Christ was called a Nazoraean, and that in earlier centuries Christians were once called Nazarenes.[39] Tertullian (Against Marcion 4:8) records that “for this reason the Jews call us ‘Nazarenes’. The first mention of the term Nazarenes (plural) is that of Tertullus in the first accusation of Paul (Acts 24:5), though Herod Agrippa II (Acts 26:28) uses the term Christians, which had been “first used in Antioch.” (Acts 11:26), and is acknowledged in 1 Peter 4:16.[40] Later Tertullian,[41] Jerome, Origen and Eusebius note that the Jews call Christians Nazarenes.

“The Christ of the Creator had to be called a Nazarene according to prophecy; whence the Jews also designate us, on that very account, Nazarenes after Him.”– Tertullian, Against Marcion 4.8)[42]

Nazarenes or Nasranis for Christians in Aramaic and Syriac

The Aramaic and Syriac word for Christians used by Christians themselves is Kristyane (Syriac ܟܪܣܛܝܢܐ), as found in the following verse from the Peshitta:

Acts 11:26b .ܡܢ ܗܝܕܝܢ ܩܕܡܝܬ ܐܬܩܪܝܘ ܒܐܢܛܝܘܟܝ ܬܠܡܝܕܐ ܟܪܣܛܝܢܐ ..

Transcription: .. mn hydyn qdmyt ᵓtqryw bᵓnṭywky tlmydᵓ krsṭynᵓ.

Translation: The disciples were first called Christians at Antioch

Likewise “but if as a Christian, let him not be ashamed, but glorify God in this name” (1 Peter 4:16), and early Syriac church texts.

However, in the statement of Tertullus in Acts 24:5, Nazarenes and in Jesus of Nazareth are both nasraya (ܢܨܪܝܐ) in Syrian Aramaic, while Nasrat (ܢܨܪܬ ) is used for Nazareth.[43][44][45] This usage may explain transmission of the name Nasorean as the name of the Mandaeans leaving Jerusalem for Iraq in the Haran Gawaita of the Mandaeans. Saint Thomas Christians, an ancient community in India who claim to trace their origins to evangelistic activity of Thomas the Apostle in the 1st century, are sometimes known by the name Nasrani even today.[46][47]

Nazarenes as Christians in Arabic literature

Although Arab Christians referred to themselves as مسيحي Masīḥī (from مسيح Masīḥ, ‘Messiah, Christ’), the term Nazarene is used in the Arabic as singular Naṣrani (Arabic: نصراني, ‘a Christian’) and plural Naṣara (Arabic: نصارى, ‘Nazarenes, Christians’) to refer to Christians in general. The term Naṣara is used many times in the Qur’an when referring to them. For example, Surat Al-Baqara (Verse No. 113) says:

2:113. The Jews say the (Naṣara) Nazarenes are not on anything, and the (Naṣara) Nazarenes say it is the Jews who are not on anything. Yet they both read the Book. And those who do not know say like their saying. Allah will judge between them their disputes on the Day of Resurrection.

— Hassan Al Fathi Qaribullah Qur’an Translation, Al-Baqara 113

In the Qur’an however Nasrani is used as a verb, not a noun coming from the Arabic root n-ṣ-r, meaning champion, or supporter, the meaning is elucidated on in Surah Al-Imran, Aya 50-52 where the prophet Isa, asks who will become supporters of me (Ansar-i) for the sake of God, the Hawariyun (the Apostles\ Followers) answer that they will become the Ansar. The same root comes in reference to the Ansar, those that sheltered the prophet Muhammad in Yathrib.

Nazarenes as Christians in Hebrew literature

In Rabbinic and contemporary Israeli modern Hebrew, the term Notzrim (plural) (Hebrew: נוצרים), or singular Notzri (נוצרי) is the general official term for ‘Christians’ and ‘Christian’,[48] although many Messianic Jews prefer Meshiykiyyim (Hebrew: משיחיים) ‘Messianics’, as used in most Hebrew New Testament translations to translate the Greek Christianoi.[49][50]

Nazarene and Nazarenes in the Talmud

The first Hebrew language mentions of Notzri (singular) and Notzrim (plural) are in manuscripts of the Babylonian Talmud; these mentions are not found in the Jerusalem Talmud.[51] Notzrim are not mentioned in older printed editions of the Talmud due to Christian censorship of Jewish presses.[52] Notzrim are clearly mentioned in Avodah Zarah 6a, Ta’anit 27b, and may be reconstructed in other texts such as Gittin 57a.[53]

- Avodah Zarah (‘foreign worship’) 6a: “The Nazarene day, according to the words of R. Ishmael, is forbidden for ever”[54]

- Taanit ‘On fasting’ 27b: “Why did they not fast on the day after the Sabbath? Rabbi Johanan said, because of the Notzrim“

Samuel Klein (1909)[55] proposed that the passage in Gittin (‘Documents’) 57a, which is one of the most controversial possible references to Jesus in the Talmud, may also have included reference to “Yesu ha Notzri” warning his followers, the Notzrim, of his and their fate.[56]

An additional possible reference in the Tosefta where the text may have originally read Notzrim (‘Christians’) rather than Mitzrim (‘Egyptians’)[57] is “They said: He went to hear him from Kfar Sakhnia[58] of the Egyptians [Mitzrim] to the west.” where medical aid from a certain Jacob, or James, is avoided.[59]

There are no Tannaitic references to Notzrim and few from the Amoraic period.[60] References by Tannaim (70–200 CE) and Amoraim (230–500 CE) to Minim are much more common, leading some, such as R. Travers Herford (1903), to conclude that Minim in Talmud and Midrash generally refers to Jewish Christians.[61]

Yeshu ha Notzri

Main article: Jesus in the Talmud

The references to Notzrim in the Babylonian Talmud are related to the meaning and person of Yeshu Ha Notzri (‘Jesus the Nazarene’) in the Talmud and Tosefta.[52] This includes passages in the Babylonian Talmud such as Sanhedrin 107b which states “Jesus the Nazarene practiced magic and led Israel astray” though scholars such as Bock (2002) consider the historicity of the event described is questionable.[62][63] The Jerusalem Talmud contains other coded references to Jesus such as “Jesus ben Pantera”,[64] while the references using the term notzri are restricted to the Babylon Talmud.[65][66] (See main article Jesus in the Talmud for further discussion).

“Curse on the Heretics”

Main articles: Birkat haMinim and Heresy in Judaism

Two fragments of the Birkat haMinim (‘Curse on the heretics’) in copies of the Amidah found in the Cairo Geniza include notzrim in the malediction against minim.[67][68][69] Robert Herford (1903) concluded that minim in the Talmud and Midrash generally refers to Jewish Christians.[70]

Toledot Yeshu

Main article: Toledot Yeshu

The early medieval rabbinical text Toledoth Yeshu (History of Jesus) is a polemical account of the origins of Christianity which connects the notzrim (‘Nazarenes’) to the netzarim (‘watchmen’ Jeremiah 31:6) of Samaria. The Toledot Yeshu identifies the leader of the notzrim during the reign of Alexander Jannaeus as a rebellious student mentioned in the Baraitas (traditions outside the Mishnah) as “Yeshu ha-Notzri“.[citation needed] This is generally seen as a continuation of references to Jesus in the Talmud[71] although the identification has been contested, as Yeshu ha-Notzri is depicted as living circa 100 BCE.[72] According to the Toledot Yeshu the Notzrim flourished during the reign of the Hasmonean queen Alexandra Helene Salome among Hellenized supporters of Rome in Judea.[73]

“Nazarenes” for Christians in late Medieval and Renaissance Hebrew literature

The term Notzrim continued to be used of Christians in the medieval period. Hasdai Crescas, one of the most influential Jewish philosophers in the last years of Muslim rule in Spain,[74] wrote a refutation of Christian principles in Catalan which survives as Sefer Bittul ‘Iqqarei ha-Notzrim (‘Refutation of Christian Principles’).[75]

Modern Hebrew usage

As said above, in Modern Hebrew the word Notzrim (נוצרים) is the standard word for Christians, but Meshiykhiyyim (Hebrew: משיחיים) is used by many Christians of themselves, as in the BFBS New Testament of Franz Delitzsch; 1 Peter 4:16 “Yet if any suffer as ha-Meshiykhiyyim (Hebrew: משיחיים), let them not be ashamed, but let them glorify God in that name.”[76][77] In the Hebrew New Testament Tertullus‘ use of Nazarenes (Acts 24:5) is translated Notzrim, and Jesus of Nazareth is translated Yeshu ha Notzri.[78]

Possible relation to other groups

Pliny and the Nazerini (1st century BCE)

Pliny the Elder mentioned a people called the Nazerini in his Historia Naturalis (Book V, 23).[79] Bernard Dubourg (1987) connects Pliny’s Nazerini with early Christians, and Dubourg dates Pliny’s source between 30 and 20 BCE and, accounting for the lapse of time required for the installation in Syria of a sect born in Israel/Judea, suggests the presence of a Nasoraean current around 50 BCE.[80] Pliny the Elder indicates[81] that the Nazerini lived not far from Apamea, in Syria in a city called Bambyx, Hierapolis or Mabog. However it is generally thought that this people has no connection to either Tertullus’ description of Paul, nor to the later 4th century Nazarenes.[82] Pritz, following Dussaud, connects Pliny’s 1st century BCE Nazerini, to the 9th century CE Nusairis.[citation needed]

Nazarenes and Ephanius’ Nasaraioi (4th century CE)

Main article: Nazarene (sect)

The testimonies of Epiphanius, Philastrius, and Pseudo-Tertullian may all draw in part from the same lost anti-heretical works of Hippolytus of Rome, mentioned as the Syntagma by Photius, and Against all Heresies by Origen and Jerome.[83]

Epiphanius mentions a sect called the Nasaraeans (Nasaraioi), whom he distinguishes from the Jewish-Christian sect of the Nazoraeans (Nazoraioi). He reports them as having pre-Christian origins.[84] He writes: “(6,1) They did not call themselves Nasaraeans either; the Nasaraean sect was before Christ, and did not know Christ. 6,2 But besides, as I indicated, everyone called the Christians Nazoraeans,” (Adversus Haereses, 29.6).[85] The sect was apparently centered in the areas of Coele-Syria, Galilee and Samaria, essentially corresponding to the long-defunct Kingdom of Israel.[86] According to Epiphanius they rejected temple sacrifice and the Law of Moses, but adhered to other Jewish practices. They are described as being vegetarian.[87] According to him they were Jews only by nationality who lived in Gilead, Basham, and the Transjordan. They revered Moses but, unlike the pro-Torah Nazoraeans, believed he had received different laws from those accredited to him.

Epiphanius’ testimony was accepted as accurate by some 19th-century scholars, including Wilhelm Bousset, Richard Reitzenstein and Bultmann.[citation needed] However Epiphanius testimony in this regard, which is second-hand, is in modern scholarship read with more awareness of his polemical objectives to show that the 4th century Nazarenes and Ebionites were not Christian.[88]

Mandaeans

Main article: Mandaeans

See also: Nazarene (sect) § Nasoraean Mandaeans, and Mandaean priest

The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran use the term Nasoraean in their scroll, the Haran Gawaitha, to describe their origins in, and migration from Jerusalem: “And sixty thousand Nasoraeans abandoned the Sign of the Seven and entered the Median Hills, a place where we were free from domination by all other races.”…[89]

Theories on the origins of the Mandaeans have varied widely. During the 19th and early 20th centuries Wilhelm Bousset, Richard Reitzenstein and Rudolf Bultmann argued that the Mandaeans were pre-Christian, as a parallel of Bultmann’s theory that Gnosticism predated the Gospel of John.[90] Hans Lietzmann (1930) countered with the argument that all extant texts could be explained by a 7th-century exposure to, and conversion to, an oriental form of Christianity, taking on such Christian rituals as a Sunday Sabbath. Mandaean lead amulets have been dated to as early as the 3rd Century CE and the first confirmed Mandaean scribe using colophons copied the Left Ginza around the year 200 CE.[91]: 4

Scholars of Mandaeans considered them to be of pre-Christian origin.[92] They claim John the Baptist as a member (and onetime leader) of their sect; the River Jordan is a central feature of their doctrine of baptism.[93][94][95]

Leave a comment