The Royal Janitor

Exisenthower’s Sword

Victoria Rosemond Bond spent allot of time watching her giant flat screen TV now that she surrendered the care of Baby Her to Starfish. This was done according to her wife’s instructions. There was a giant oak on the old road to sisters. Her was to be placed under this tree in a special basket woven from hemp stalk.

When the President appeared on the evening new, he was with Pete Hesgeth, and Russ Vought , the author of Project 2025. Regardless of the Governor’s claim that Port;and was “war ravaged” was allot of hyperbole. motjomg but pure fiction. there is Trump on TV annpindong how the invsion of the Rose City will go down.

Pete Hesgeth and Russ will join the military convoy that is formin in Boise. Russ will dredded like a Puritan Priest. He will be carrying the New Christian Constitution he help author, as a heaed of Project 2025. He will read certain passages when the two comets apper of Oregon on October 8th. He will perfoemd a Christian Cleansing of what he twred

THE WICCAN CAPITOL OF THE WORLD

Hesgeth will wave a sword, that will be a sginal for Donald Trump to land at the Portland airpord. On board, is a speciall crown…..

“ENOUGH!” Shouted Victoria, and she picked up her phone to call Starfish – when he phone rang in her hand.

“There a Lombard sword!” Victoria and Star shouted at the same time! “How stupid can we be!”

“We must warn the world. You once said Christianity is a fraud, and you can prove it. Charlie Kirk was going to speak at the UofO. You must go there and….

TELL THE TRUTH!

To be continued

Donald Trump, at the time president of the United States, listens to then-Office of Management and Budget Acting Director Russ Vought deliver remarks prior to Trump signing executive orders on Oct. 9, 2019, in the Roosevelt Room of the White House. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

General Dwight D. Eisenhower possessed several notable swords throughout his military career, including a West Point saber, a Sword of Honor from London, and an honorary saber from the Netherlands. The swords have gained renewed public attention due to a recent controversy involving the Trump administration.

Eisenhower’s swords

- Netherlands honorary saber: In 1947, Queen Wilhelmina presented Eisenhower with an honorary saber for his role in liberating the Netherlands during World War II.

- This saber is made of gold and silver with embedded gemstones and features engravings of the Dutch coat of arms and the message, “Queen Wilhelmina to General DD Eisenhower”.

- The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas, holds this saber.

- London Sword of Honor: The City of London also awarded Eisenhower a Sword of Honor in 1947.

- Eisenhower regarded this gift as a symbol of the unity between the United States and the United Kingdom.

- This sword is currently on loan from the Eisenhower family to the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum for a temporary exhibit.

- West Point Officer’s Saber: Eisenhower, a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point (class of 1915), also possessed his ceremonial Model 1902 Army Officer’s Saber.

- This saber, along with the Sword of Honor, is temporarily displayed at the Nixon Library.

- Napoleon Bonaparte’s sword: In 1945, General Charles de Gaulle of France presented Eisenhower with one of Napoleon’s personal swords. It had been worn by Napoleon when he was First Consul.

- The sword is housed at the Eisenhower Presidential Library.

Recent controversy surrounding the swords (September–October 2025)

The Eisenhower swords were recently in the news due to a diplomatic dispute involving a proposed gift for King Charles III.

- Request for a sword: During a state visit by President Donald Trump to the UK in September 2025, the administration requested an original Eisenhower sword from the presidential library to give to King Charles.

- Library director’s refusal: Todd Arrington, the library director, refused the request. He stated that the original artifacts belonged to the U.S. government and the American public and were legally required to be preserved by the National Archives.

- The outcome: In the end, a replica West Point cadet saber was given to King Charles instead.

- Director’s resignation: Weeks later, Arrington was forced to resign. He told reporters that a supervisor at the National Archives told him he had lost the administration’s trust.

Library chief asks to be reinstated after tussle over sword for King

Todd Arrington refused to let Trump give King Charles a sword which had belonged to Dwight D Eisenhower during the president’s recent state visit to the UK

, Washington

Friday October 03 2025, 12.05am BST, The Times

A presidential library director removed from his post after he refused requests to give an original sword belonging to Dwight D Eisenhower to King Charles during President Trump’s state visit to Britain has made a public plea to be reinstated.

Todd Arrington said he was told he was being removed from the role of director of Eisenhower’s library on Monday after he objected to requests from the Trump administration to bestow an authentic sword to the King and Queen.

“I’m very sad and upset, and frankly devastated, and I have tried to reach out to higher-ups in the National Archives to basically say, I will do whatever it takes to reverse this,” Arrington told the Daily Mail on Thursday. “I will personally apologise to anyone who needs to be apologised to.”

• Sign up for The Times’s weekly US newsletter

Arrington said he had told state department officials who requested the sword that he was unable to release any artefacts because they were gifts to the museum and belonged to the American people. He offered a replica instead, he said, adding: “The person I talked to there was lovely and polite and friendly and totally understanding of me saying, ‘I can’t give you an artefact out of our museum, but I can help you find something else.’”

Advertisement

During Trump’s state visit to the UK last month, Arrington said he had been contacted by a superior at the National Archives and thanked for his help. However, on Monday he was informed that he was being removed from the job and accused of leaking information after talking to colleagues about the sword, he said.

Arrington spoke out after CBS News reported that he had resigned.

Todd Arrington, a career historian, ran the library in Kansas

ARCHIVES.GOV

Dwight D Eisenhower, the 34th president of the United States

FOX PHOTOS/GETTY IMAGES

Melania Trump, the first lady who was responsible for choosing the gifts for last month’s visit, had picked the sword as a symbol of the enduring strength of the postwar British-American relationship.

Trump eventually gave the King a replica of Eisenhower’s West Point sabre from the military academy.

In a statement last month, Buckingham Palace said that the replica symbolised profound respect and was a reminder of the historical partnership that was critical to winning the Second World War.

Advertisement

“The sword also symbolises the enduring values and co-operative spirit that continues to define the relationship between the United States and Great Britain,” the palace added.

• King Charles ‘perplexed’ by Prince Harry’s accusation of sabotage

Eisenhower had a number of swords, including a sword of honour received in 1947 by Lord Inverchapel, the former British ambassador, on behalf of the City of London for his service as Allied supreme commander in the Second World War.

The 1947 Sword of Honour

ALAMY

Tom Beasley, the swordsmith who crafted the City of London sword

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHIC AGENCY/GETTY IMAGES

The original, made by the renowned British swordsmith Tom Beasley and a number of elderly craftsmen at the Wilkinson Sword company, is on display at Richard Nixon’s presidential library, along with the original West Point sabre.

Sources told CBS News that although the Trump administration was unhappy with Arrington’s objections, no one expressed discontent directly to him. Four officials involved in the state visit were unaware that he had left his job and said the White House had played no role in his exit.

Advertisement

Eisenhower’s presidential library in Abilene, Kansas

ALAMY

Arrington, a career historian, had served as the director of the Dwight D Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home in Abilene, Kansas, since August 2024.

The site, where Eisenhower is buried, is operated by the National Archives and Records Administration. In February Trump fired Colleen J Shogan, the national archivist and Nara chief administrator. Marco Rubio is acting as the incumbent.

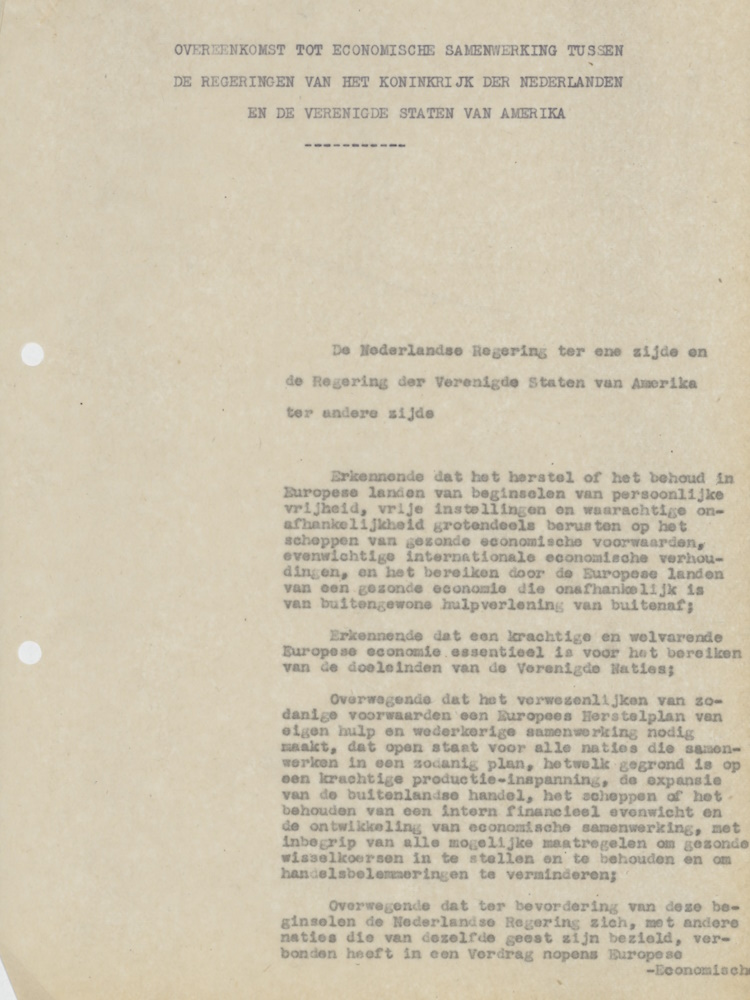

A Sabre for Eisenhower: Forging Transatlantic Bonds for the Twentieth Century

Dutch-American Stories: #21

Written by Jorrit Steehouder

Using a royal gift as a starting point, Jorrit Steehouder shows how ties between the United States and the Netherlands were forged through rituals and symbols, as well as through personal friendships.

On October 14th, 1947, a crisp and sunny autumn day, General Dwight D. Eisenhower celebrated his 57th birthday in style. At the Dutch embassy, in the heart of Washington, D.C., ambassador Eelco van Kleffens presented the legendary hero of World War II with an ‘honorary sabre’. It was not a conventional blade. Weighing nearly five pounds, the gold-encrusted sabre was embedded with hundreds of gemstones and had been meticulously handcrafted by one of the most skillful goldsmiths in The Netherlands: Brom’s Edelsmederij in Utrecht. In addition to its impressive appearance, the sabre surpassed the ordinary because it was a symbol of profound gratitude – from none other than the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina herself. The sabre’s scabbard was engraved with the words: ‘In grateful memory of the glorious liberation’. The blade itself was inscribed on both sides with ‘E pluribus unum’ and ‘Je maintiendrai’, the national mottos of the United States and The Netherlands.

The sabre was more than just a symbol of gratitude. Obviously, the liberation of The Netherlands by American forces (and indeed also Canadian and Polish) in May 1945 added a new layer to the already deep historical bond between the two countries. Wilhelmina’s gift harkened back to the existing ties, and, by celebrating the recent American sacrifice and valor, she helped to forge a lasting transatlantic bond of friendship between United States and The Netherlands. The sabre for Eisenhower, in that sense, symbolized the connection between two nations across the Atlantic in past and present, as well as in the future. Like the sabre itself, these connections were forged under pressure, particularly during and immediately after the war.

These were not all shiny celebrative moments. In fact, cementing lasting transatlantic bonds between The Netherlands and the United States entailed hard and painstaking work of diplomats, often out of the public gaze, going through piles and piles of paperwork and sometimes straining negotiations in backrooms, creating durable institutional and personal connections in the process. This was the job of men like Hans Hirschfeld and Ernst van der Beugel, who were stationed in Washington in the post-war years to explain to the American policymakers of the State Department why Europe needed post-war American economic assistance. Both the public and symbolic display of friendly relations (like gifting the sabre) and the laborious work of diplomats, however, are essential to forging durable relations.

Shortages of food and fuel

Forging Eisenhower’s sabre had taken well over a year. It was commissioned in July 1945, shortly after the end of the war in Europe. After a phase of planning, designing, and consulting between the brother-goldsmiths Jan Eloy Brom and Leo Brom, the Ministry of War, and Queen Wilhelmina herself, the processing of manufacturing the sabre could begin. There was even an effort at acquiring a better sense of what ‘Ike’ would appreciate in a sabre and how the makers could provide it with a personal touch that would befit the General. Most of the gemstones used for the sabre’s decoration had to be obtained, cut, and polished in France, which considering the large number, obviously took a long time. But there was another reason as well. As gas and coal remained rationed in The Netherlands during the immediate post-war years, the ovens required to heat the precious metals could not be used to their full capacity. In a sense, the making of Eisenhower’s honorary sabre went hand in hand with the gradual recovery of European industry and was plagued by the same bottlenecks that slowed Europe’s economic recovery: shortages of coal, oil, and food.

The Marshall Plan and the European reaction

In the months before Eisenhower was presented with the sabre, American policymakers were dealing with the issue of economic recovery, along with the shortages of fuel and food. In May 1947, Will Clayton, the Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs, had cautioned that without ‘prompt and substantial aid from the United States, economic, social and political disintegration will overwhelm Europe.’ Immediate action had to be taken to ‘save Europe from starvation and chaos,’ which could lead to a communist takeover. Clayton’s warning set the wheels of state in motion. Secretary of State George C. Marshall announced a large-scale program of economic assistance to European countries in a speech at Harvard University on 5 June 1947. Yet the Marshall Plan, as it became known later, did not resemble an actual plan yet. Many things were unclear: how would the Europeans receive aid, how would it be administered, how much would it amount to. And Congress of course had the final say. Instead of providing specifics, Marshall called on the Europeans to provide ways through which the American government could help them with economic recovery. In the words of Marshall, this was the ‘business of the Europeans.’

For an audio recording of Marshall’s speech

Dutch diplomats enterpreting American goals

The leader of the Dutch delegation, Hans Hirschfeld, turned out to be an excellent interpreter of ‘vague’ American demands. Good personal contacts between Dutch and American policymakers enabled Europeans, Hirschfeld in particular, to make sense of what the Americans meant with these ‘constructive plans’. Clayton had been quite clear in off-the-record meetings with his European counterparts in Paris, shedding the ambiguousness of his colleagues in Washington. He expected nothing less than the eventual creation of large European market based on the American model. Clayton knew that it was not realistic to expect the Europeans to set up a full-blown European economic federation at this stage, but Hirschfeld was a smart thinker and developed an actionable plan for intra-European payments that would bring Clayton’s eventual goal one step closer.

In proposing increased European currency convertibility, Hirschfeld was acting along the lines envisioned by Clayton and in the spirit of the American government’s ultimate ideas for an economically integrated European continent. In addition, Hirschfeld was an early advocate of German economic recovery in a European framework. This was something that the French resented, but the Americans considered it necessary for Europe’s recovery. Hirschfeld also fully grasped the urgency of the moment. To him the Marshall Plan presented a unique opportunity, not just for his own country, but for Europe as a whole. Failure to take further steps on the road towards European cooperation, he noted, would ‘promote a tendency to autarchy’, which ‘would mean that the countries of Europe would become more and more isolated from each other, as occurred at the end of the first world war’. By reminding his European colleagues of the social and economic chaos that haunted the continent in the interwar years, he deliberately struck an emotional chord.

Eventually, the Paris Conference referred Hirschfeld’s plan to a study group, because its purpose was beyond the conference’s mandate. Meanwhile, in Washington, Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett was concerned that the lists of economic requirements constrained European thinking to ‘self-help’. Or, in other words, it limited European economic planning to policies that stimulated integration and mutual help between its own economies, instead of furthering economic dependency on America. By late August, Washington became seriously worried about the Paris Conference and the pending European reaction to Secretary Marshall’s speech. The total sum for the ‘sixteen shopping lists’ amounted to a staggering $28 billion. This was considered unacceptable to the American public, and Hirschfeld acknowledged that even before the Americans voiced their objections. Clayton’s emphasis on ‘financial and multilateral arrangements’ to achieve European ‘self-help’ was also a cause of concern. Monetary multilateralism, as Hirschfeld had proposed, fell short of American ambitions and did not help to sell the Marshall Plan to the American public. The State Department sent George Kennan, one of their top diplomats to Paris to straighten things out. Kennan told the Europeans to shift their emphasis from the ‘long-run gains of European economic integration’ to the ‘more urgent short-run needs’. This would make the plan more acceptable to American public opinion. After all, American citizens could very well understand the needs of hungry Europeans.

Hirschfeld at the State Department

The context of the Marshall Plan and its European reception determined the setting in which the honorary sabre was presented to Eisenhower. Initially, the Dutch Ministry of War had opted for a military ceremony in Washington. Eisenhower, after all, was honored for his military achievements. He was clearly a military man and not a diplomat or politician. Yet on the appointed day the ceremony took on a different hue. The reception hosted by Van Kleffens, attended by many American dignitaries, transformed it into a diplomatic setting emphasizing the strong ties between the two countries. In view of the large-scale public relations campaign to ‘sell’ the Marshall Plan to the American voters, this was a sensible move. Expressing gratitude to a country in the midst of the ‘second act’ in the liberation of Europe, as it was dubbed, could potentially win over an American public skeptical of dispatching more aid to Europe.

A week before the ceremony Hirschfeld also arrived in Washington. He had boarded the Queen Mary in London to cross the Atlantic, together with American Congressional leaders who had been on a tour to acquaint themselves with the dire economic state of European countries, in particular Germany. Several representatives of the Committee for European Economic Cooperation also sailed on the Queen Mary, including the French Robert Marjolin, the British Frank Figgures, and Hirschfeld’s fellow Dutch citizen Ernst van der Beugel. The atmosphere aboard the Queen Mary had been very friendly, as some of the travelers later recalled. Hirschfeld was unable to attend the reception for Eisenhower, as he had to answer questions from American policymakers about the European response to Marshall’s speech. In a painstaking last-minute effort, and under considerable American pressure, the Europeans had reduced their request for aid to acceptable levels. The meetings between the American and European delegations in Washington had been very complex and technical, but in the end did help to convince American policymakers of the feasibility of the plan, as well as of European intentions regarding economic recovery and mutual aid.

Diplomats understanding each other

The intense months of negotiations in Paris and Washington had also been a process of rapprochement between American and European diplomats. In Paris, Hirschfeld had shown himself a listener, with a good ear for American intentions for Europe. This had enabled him to closely align the European policies of The Netherlands, such as intra-European payments and German recovery, with American aims. On a personal level, he understood the difficulties the Americans faced. Hirschfeld knew it would be very difficult to sell the Marshall Plan to the American public, and that Europeans should be sensitive to the American domestic situation. Vice versa, American diplomats had gained a better understanding of Europe. Kennan had understood that there was a fine line between what the Americans expected from Europeans in the short run, and what they were prepared to do. Clayton had intimated to his colleagues that lowering the request for economic assistance had been ‘an extremely delicate matter of deep concern’ for Europeans, who could not be expected to accept lowered living standards for much longer.

This episode in Dutch-American history shows that relations amount to more than what catches the public eye. Rituals, symbols, and expressions of gratitude certainly contribute to public perceptions of Dutch-American relationship, but do not fully explain the resilience of it. Dutch-American relations have been built on common history, as well as on common interests. In the case of the Marshall Plan, Dutch and American interests clearly aligned, and men like Hirschfeld and Clayton understood this. This gradual institutionalization of our countries’ relations makes them durable. It makes it possible to address difficult issues, such as the Dutch military interventions in Indonesia, starting in July 1947, a matter of deep concern to the United States.

Eisenhower’s sabre of honor remains in the collection of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas, where it is currently on display in an exhibition of the various tokens of gratitude Eisenhower received from all over the world for his role in the Allied victory in the Second World War. As such, it continues to symbolize the deep historical and emotional bonds between The Netherlands and the United States.

About the author

Jorrit Steehouder is Assistant Professor in the History of International Relations at Utrecht University. His research interests include the history of European integration, transatlantic relations, the history of exile communities during World War II, global multilateralism, and the history of Central- and Eastern Europe. He defended his PhD dissertation Constructing Europe: Blueprints for a New Monetary Order, 1919-1950 in January 2022 at Utrecht University.

About the blogseries

This is the twenty-first installment in a monthly series of blogs telling stories about the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch peoples. Authors from both countries present accounts of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to give as full a picture as possible of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that happened place over hundreds of years of shared history. Not all these stories are ‘feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not diminish this friendship but, rather, deepens it.

New Trump budget chief wrote Project 2025’s agenda for empowering the presidency

By:Jennifer Shutt-November 30, 20248:00 am

Donald Trump, at the time president of the United States, listens to then-Office of Management and Budget Acting Director Russ Vought deliver remarks prior to Trump signing executive orders on Oct. 9, 2019, in the Roosevelt Room of the White House. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

WASHINGTON — Incoming White House budget director Russ Vought has spent much of his career learning the detailed, often convoluted mechanisms that make up the Office of Management and Budget.

The agency, little known outside Washington, D.C., is relatively small compared to the rest of the federal government, but it acts like a nucleus for the executive branch and holds significant power.

OMB is responsible for releasing the president’s budget request every year, but also manages much of the executive branch by overseeing departments’ performance, reviewing the vast majority of federal regulations and coordinating how the various agencies communicate with Congress.

Vought was deputy director, acting director and then director at OMB during Trump’s first term.

Before that Vought worked as vice president of Heritage Action for America, policy director for the U.S. House Republican Conference, executive director of the Republican Study Committee and a legislative assistant for former Texas Republican Sen. Phil Gramm. He has an undergraduate degree from Wheaton College and a law degree from George Washington University Law School.

Following Trump’s first term in office, Vought founded the right-leaning Center for Renewing America. The group’s mission is “to renew a consensus of America as a nation under God with unique interests worthy of defending that flow from its people, institutions, and history, where individuals’ enjoyment of freedom is predicated on just laws and healthy communities.”

Cutting government spending

Vought outlined his agenda for the next four years in Project 2025, a 922-page document from the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation that led to speculation during the presidential campaign about what Trump would seek to do without Congress, including in areas that constitutionally fall within the legislative branch, like government spending.

The Democratic presidential nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris, repeatedly tried to tie Project 2025 to Trump and his campaign, and they sought to distance themselves from its proposals. But Trump has since nominated some of its authors or contributors to run federal departments and agencies.

Vought, in a 26-page chapter on the executive office of the president, wrote the OMB director “must ensure the appointment of a General Counsel who is respected yet creative and fearless in his or her ability to challenge legal precedents that serve to protect the status quo.”

Trump, Vought and many others are bullish about cutting government spending, but will likely run into legal challenges if they try to spend more or considerably less than lawmakers approve in the dozen annual government funding bills.

Budget request

One of Vought’s most visible responsibilities will be releasing the president’s annual budget request, a sweeping document that lays out the commander-in-chief’s proposal for the federal government’s tax and spending policy.

The president’s budget, however, is just a request since Congress has the constitutional authority to establish tax and spending policy.

Lawmakers on Capitol Hill write the dozen annual government funding bills that account for about one-third of annual federal spending. The rest of the federal government’s spending comes from Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, which are classified as mandatory programs and mostly run on autopilot unless Congress approves changes and the president signs off on a new law.

That separation of powers led to frustration during Trump’s first term in office and will likely do so again, since he spoke during the 2024 campaign about using “impoundment” to prevent the federal government from spending money Congress has approved.

Trump withheld security assistance funding from Ukraine during his first term in office, leading to one of his two impeachments and a ruling from the Government Accountability Office —a nonpartisan government watchdog — that he had violated the law.

“Faithful execution of the law does not permit the President to substitute his own policy priorities for those that Congress has enacted into law,” GAO wrote. “OMB withheld funds for a policy reason, which is not permitted under the Impoundment Control Act (ICA). The withholding was not a programmatic delay. Therefore, we conclude that OMB violated the ICA.”

Trump spoke on the campaign trail about using “impoundment” to drastically cut government spending, but that would likely lead to lawsuits and a Supreme Court ruling.

Vought’s think tank, Center for Renewing America, published analysis of presidents using impoundment throughout the country’s history, with the authors concluding the Impoundment Control Act is unconstitutional.

‘Every possible tool’

Vought sought to defend the president’s budget request in his chapter in Project 2025, writing that though “some mistakenly regard it as a mere paper-pushing exercise, the President’s budget is in fact a powerful mechanism for setting and enforcing public policy at federal agencies.”

He signaled the second Trump administration would be more nuanced in its interpretation of presidential authority.

“The President should use every possible tool to propose and impose fiscal discipline on the federal government.” Vought wrote. “Anything short of that would constitute abject failure.”

Vought also wrote about the management aspect of OMB’s portfolio, pressing for political appointees to have more authority and influence than career staff.

“It is vital that the Director and his political staff, not the careerists, drive these offices in pursuit of the President’s actual priorities and not let them set their own agenda based on the wishes of the sprawling ‘good government’ management community in and outside of government,” Vought wrote. “Many Directors do not properly prioritize the management portfolio, leaving it to the Deputy for Management, but such neglect creates purposeless bureaucracy that impedes a President’s agenda—an ‘M Train to Nowhere.’”

n

Leave a comment