Hippie House

A Televion Show

by

John Presco

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

To: Neil Laudati

Assistant City Manager of Springfield

My name is John Presco. We have met. I have an idea for a television show about an old male hippie, and a young female hippie who are ordered to live together for two years to prove they can do so in peace.

Synopsis: The old hippie brought a lawsuit against the City of Eugene for not protecting his Constitutional Rights that were assailed in Ken Kesey Square, by a consortium of new radicals, anarchists, food goblins, wiccans. devils, and sleep warriors, and wiccans – after he befriends Belle Burch – who fails to tell Mr. Presco who her friends are, fearing he would end their friendship if he did. I find out. I get death threats. A message is posted in Mayor Kitti Piercis Facebook – and is taken down! Alley Valkyrie reposts it on a fake Eugene Abuser side. Just Google my name, and there we be. Belle and….The Beast!

What inspired this tale, is the house I found for sale in Springfield. It should be a hippie museum and monument. Perhaps Home and Garden TV would do broadcast? Too bad we didn’t save Herbert Armstrong’s radio station. There is an interest in offbeat Christian messages. The silencing od Kirk’s voice, should tell us all, we are struggling to be heard. How many billions have been sent to oppress the Hippie-left. This money can go to help the homeless. Our show will promote – visible peace! We will have guests.

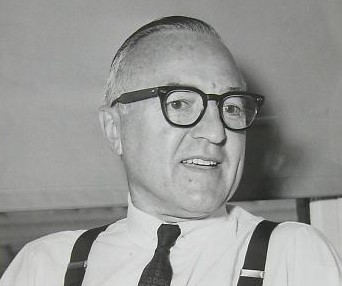

Ernest Besig, Korematsu’s lawyer

Here is the account of the ordinance passed in Belmont to rid the city my ancestors founded of “filthy hippies”. Does the use of this word denote being nude in front of the opposite sex you are not married to? How about a group of male roommates, and you are a naked un-married woman? The real FILTH has found a home in the dirty minds of politicians who whore around for votes!

“Belmont adopted an ordinance last night redefining the word “family” and the American Civil Liberties Union said this morning that it intends to challenge this ordinance in court. The action defines family as any persons related by blood. marriage, adoption, plus not more that two unrelated persons, or unrelated persons – not exceed a total of three living in a single family dwelling. During the hearings proceeding introduction of the ordinance, proponents of the measure stated it would ‘clean out those nests of filthy hippies from the cities neighborhoods”

The ACLU wrote to request a copy of the anti-hippie ordinance from city officials, who replied there was no anti-hippie ordinance but sent them the measure approved last night. In a second letter dated June 20 the ACLU charged the measure was unconstitutional.

Ernest Besig executive director of of the ACLU in San Francisco, said today that the legislation was brought to his attention by Belmont’s residents who are not hippies, just ordinary family. If the ordinance approved late last night is applied, and if any here alleged hippies are arrested, we will intervene in the arrested behalf, and challenge the measure in the courts, Besig said.

Besig said the measure would prohibit, for instance, four airline stewardesses from living in a single family home in Belmont. This is unreasonable and arbitrary.” he said. Besig is a fifteen year resident of Belmont. The measure passed on a 3-0 vote with condition that Joseph Zucca and Morton Poldolsky absent.

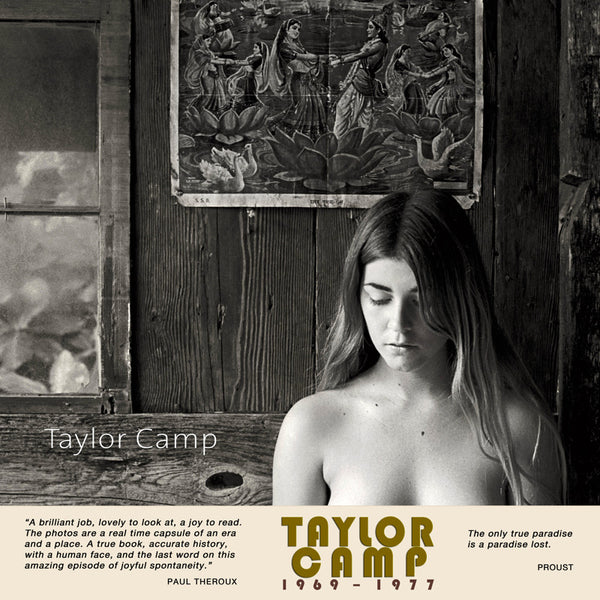

Above is a photograph of a beautiful hippie that lived in Taylor Camp, founded by Howard Taylor, the brother of Liz Taylor. There was much legal action around this famous commune.

John Presco

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taylor_Camp

https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Ernest-Besig-94-ACLU-legal-crusader-3058442.php

Taylor Camp was a small settlement established in the spring of 1969 on the island of Kauai, Hawaii. It covered an area of 7 acres (2.8 ha) and at its peak it had a population of 120.[1] It began with thirteen hippies seeking refuge from the ongoing campus riots and police brutality in the United States.[2] They were arrested for vagrancy but Howard Taylor, brother of movie star Elizabeth, bailed them out of jail and invited them to settle on a beachfront property he owned.[3] Eduardo Malapit prosecuted the original Taylor campers;[4] later as mayor, he campaigned to shut down the camp.[5]

Ernest Besig, 94, ACLU legal crusader

By Larry D. Hatfield,OF THE EXAMINER STAFFNov 18, 1998

Ernest Besig, founder of the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California and a lifelong defender of unpopular clients from striking longshoremen to interned Japanese to conscientious objectors, has died.

Mr. Besig, who retired as executive director of the ACLU in 1971 after nearly four decades of battling for civil liberties, died in a Sonoma convalescent home Friday. He was 94.

“Ernie Besig played a larger-than-life role in shaping the ACLU of Northern California, an organization he imbued with the integrity necessary to be respected and heard,” said Dorothy Ehrlich, the civil liberties organization’s current executive director.

“Ernie had a real influence on shaping the political and legal history of California and he built an organization that continues to play this invaluable role.”

Although he involved the ACLU in causes from the 1934 San Francisco Bloody Thursday strike to the anti-Vietnam War movement, perhaps Mr. Besig’s proudest achievement was pursuing a case the ACLU lost.

Under his leadership, the ACLU challenged the relocation and forced detention of Japanese Americans from the West Coast during World War II. Taking the case of Fred Korematsu of Oakland, who was jailed when he refused to be relocated, the ACLU challenged the exclusion and detention laws as violating basic constitutional rights.

The case was lost on a 6-3 vote of the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld all the war measures on the grounds of military necessity, but the ACLU’s position eventually was vindicated when reparations were paid to relocated Japanese Americans nearly 50 years later.

Mr. Besig also investigated the “Gestapo-like” conditions at the relocation camps at Tule Lake, Manzanar and Tanforan.

During the war, the ACLU also defended the rights of conscientious objectors and the right of atheists to be objectors on moral, as opposed to religious, grounds.

A native of New York City and a law graduate of Cornell University, Mr. Besig came west during the Depression and was organizing farm workers in the fields of Southern California when he got the call to go north.

He was sent by the then-14-year-old national ACLU to defend workers against police and government attacks on strikers on the San Francisco waterfront, a dispute that was to grow into a general strike and the infamous Bloody Thursday, in which two unionists were gunned down by police.

He and his partner, Chester Williams, stayed to start the ACLU of Northern California. One of the new chapter’s first actions was a lawsuit against the cities of San Francisco and Oakland for not protecting the strikers’ First Amendment rights to free speech and assembly. They won.

He then was sent to Humboldt County, where no attorney was willing to defend strikers in the bloody Holmes-Eureka lumber strike, in which three pickets had been killed. His 30-day assignment there extended to a lifetime of service to the ACLU in Northern California.

Under Mr. Besig’s leadership, the ACLU-NC continued its defense of labor, winning full pardons for 22 Wobblies who were convicted under California’s criminal syndicalism law and aiding in the defense of labor martyrs Tom Mooney and Warren Billings, falsely convicted for the 1916 Preparedness Day bombings.

In the 1940s, the ACLU-NC succeeded in having the U.S. Supreme Court overturn the state’s anti-Okie law, which prohibited indigents from entering California.

Mr. Besig also involved the chapter in some of the first attacks on racial discrimination in the state, successfully defended hundreds of post-World War II victims of the government’s “loyalty and security” programs, defended speech rights of UC-Berkeley students during the Free Speech Movement, vigorously opposed the war in Vietnam and was an early champion of immigrant and inmate rights.

In 1957, current San Francisco poet laureate Lawrence Ferlinghetti was put on trial for selling copies of Allen Ginsberg‘s “Howl and Other Poems” at his City Lights bookstore.

With the Besig-led ACLU defending Ferlinghetti and others, the case resulted in a decision that “Howl” was not obscene and establishing the redeeming social value precedent that has protected writers and artists ever since.

“I took it (his arrest) as just another expression of a police mentality that was very prominent in that decade,” Ferlinghetti said. “We didn’t have a cent. If it hadn’t been for the ACLU, we’d be out of business forever.”

A year after Mr. Besig’s retirement, S.F. State and the ACLU established a special lectureship in political science to honor his 36 years of service to the organization. Mr. Besig also was a recipient of the Earl Warren Civil Rights Award.

Mr. Besig is survived by a daughter, Ann Forwand, of Cambridge, Mass. His wife of 42 years, Velma Snider Besig, died in 1981.

ACLU-NC spokeswoman Elaine Elinson said plans are being made to hold a memorial service for Mr. Besig early n

Nov 18, 1998

Japanese Americans arrive by truck to one of the 10 incarceration camps managed by the War Relocation Authority. Photo: Wikicommons

Investigating Tyranny

Coverage of the evacuation orders and their context intensifies in the August 1944 edition of The ACLU News, in which Besig reports on his July 1944 investigation into conditions at the Tule Lake Relocation Center: the largest of the 10 incarceration camps managed by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the federal agency charged with overseeing the camps. This camp, situated in the remote northeast corner of California, was designated for the incarceration of people whom the government had deemed “disloyal.”

In the newsletter, Besig details the darkness he and his secretary encountered there. They discovered that, for over eight months, authorities had shut people away in the stockade (the prison within the prison) without trial or hearing. The number of people in the stockade had once numbered 300; at the time of their visit, there were 18.

Besig learned that people in the stockade had “been denied all visiting privileges.” He “heard of men who had never been permitted to see children born after their detention,” and family members who “became sick with grief over the forced separation….”

The article suggests that, as Besig’s investigation deepened, further allegations of abuse emerged. He writes of evidence that internal security police “dragged certain Japanese into the administration building and beat them with baseball bats.” He reports that personnel “who came to work in the administration building the next morning… found a broken baseball bat, and had to clean up a mess of blood and black hair.”

His discovery apparently prompted camp authorities to cut the investigation short. After spending two days at the camp and interviewing a fraction of the people who had requested interviews, armed guards escorted the ACLU NorCal representatives from the premises. They later discovered that someone had poured salt into their gas tank, severely damaging their car.

Besig submitted a complaint to the WRA, and an ACLU NorCal attorney held a conference with WRA officials about the investigation. The ACLU News reports that, subsequently, the WRA “very quietly released” those imprisoned in the stockade.

Leave a comment