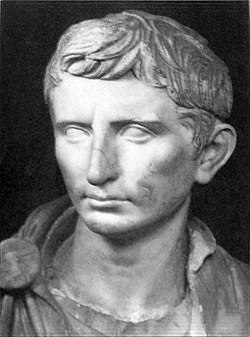

Julius Caesar, the iconic figure

Robert E. Lee

An hour ago I saw the observance of silence in New York for the human being that were assasinated by Islamic Terrorists. Did you know Marc Anthony put King Herod on David’s throne, and made him

KING OF THE JEWS?

Did you know Marc Antjony made John Hyssnscus – High Priest of the Temple of God?

WHY?

He did this because the Roman Legions could not defeat the Parthians. They kept winning, And, many Jews backed the Parthians, who became the Nation of Iran. Did Iran give their condolences to the U.S.A.? Has anyone ever put the image of Lee and Julius together? Both men owned slaves, and made slaves of the people they CONQUORED! Both men ARE LOSERS! Julius lost his life – and was betrayed by his people! Lee betrayed his people when he became a Confederate General. He killed loyal Americans as an INSURRECTIONIST Mark Anthony was an INSURRECTIONIST Does he have a statue? Go Goggle and see. Octavian has a statue. He was VICTORIUS over Antony, and caused Cleopatra to take her life. There are no statues at the 911 memorial,

John Presco

Marc Antony’s direct interactions with John Hyrcanus II were significant in establishing Roman control over Judea. During his campaigns in the region, Antony intervened in the civil war between Hyrcanus II and his rival, ultimately reinstating Hyrcanus as the High Priest. These events cemented Rome’s influence, but also led to the rise of Antipater and his son Herod, who would later become a key Roman ally.

Lee wrote a letter dated Aug. 5, 1869. He had been asked by the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association to help with a granite memorial that would remap the most fatal battle of the Civil War. The battle in Pennsylvania claimed an estimated 51,112 lives over three days, July 1-3, 1863.

Lee declined the invitation. He did not want the memorial. After warring against the United States, he spent the final five years of his life as president of a liberal arts college now known as Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia.

“I think it wiser moreover not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife and to commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered,” Lee wrote. The letter was preserved and sits in a museum at Gettysburg College.

Statue of Octavian, also known as the first Roman Emperor Augustus

The global war on terrorism wrecked relations with Iran

The most fundamental strategic error of the George W. Bush administration following the September 11, 2001, attacks was launching a “Global War on Terrorism” that failed to distinguish properly between those responsible for the 9/11 attacks and other US adversaries. This hubristic and grandiose agenda weakened US focus, alienated allies, and deprived the United States of opportunities to lessen hostility with historic foes. It put the United States on a path toward unwinnable wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, culminating in humiliating withdrawals from both.

Among the most consequential losses following the 9/11 attacks were dashed opportunities with Iran. Iranians showed sympathy to the United States after 9/11 holding candlelight vigils on the streets of Tehran. The Iranian government cooperated indirectly with the US military to topple the Taliban regime in Afghanistan and worked openly with the State Department to stabilize a new government in Kabul. It was Javad Zarif, then deputy minister for legal and international affairs of Iran, who procured a commitment from that new Afghan government to hold democratic elections and combat international terrorism. US officials have since acknowledged that Iranian pressure on the Afghan Northern Alliance allowed Hamid Karzai to become the first post-Taliban president of Afghanistan.

At the same time, Iran and the United States held a series of backchannel talks in Geneva and Paris that dealt with Afghanistan and rolling up al-Qaeda members fleeing into Iran from Afghanistan. These talks were interrupted when Bush, in his State of the Union address in 2002, included Iran, along with North Korea and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, as part of an “axis of evil.” The Iranians—no strangers to bellicose rhetoric—resumed backchannel talks with the United States after a month. However, the Bush administration showed no interest in building upon those talks to improve ties with Tehran, even ignoring Iranian warnings about the consequences of invading Iraq and subsequent overtures for broader dialogue in the aftermath of the 2003 US invasion. The Bush administration reneged on a promise to turn over leaders of the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq, a militant Iranian opposition group that had been harbored by Saddam and was at the time a US-designated foreign terrorist organization, in return for al-Qaeda figures detained in Iran. Bush also proclaimed a “Freedom Agenda” seemingly threatening Iran with regime change following similar US-engineered overthrows in Afghanistan and Iraq.

After 9/11, neoconservatives and hawks in the United States, led by the then US vice president Dick Cheney and deputy secretary of defense Paul Wolfowitz, harbored illusions that the US invasion of Iraq would boost democracy proponents throughout the Middle East and that the Islamic Republic of Iran would be the next “terrorist-sponsoring” domino to fall. Instead, Iraq turned into a quagmire and Iran, with long-standing ties to Iraqi Shi’ites and deep knowledge of the physical and political terrain, implanted itself in Iraq—where it remains to this day.

The War of Actium[1][2][3][4][5] (32–30 BC) was the last civil war of the Roman Republic, fought between Mark Antony (assisted by Cleopatra and by extension Ptolemaic Egypt) and Octavian. In 32 BC, Octavian convinced the Roman Senate to declare war on the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. Her lover and ally Mark Antony, who was Octavian’s rival, gave his support for her cause. Forty percent of the Roman Senate, together with both consuls, left Rome to join the war on Antony’s side. After a decisive victory for Octavian at the Battle of Actium, Cleopatra and Antony withdrew to Alexandria, where Octavian besieged the city until both Antony and Cleopatra were forced to commit suicide.

The war involved some of the largest Roman armies ever seen. Both Antony and Octavian’s legions were experienced veterans of previous civil wars who had fought together, many also having once served under Julius Caesar. The two did however raise their own legions separately.

Following the end of the war, Octavian brought peace to the Roman state that had been plagued by a century of civil wars, marking the beginning of the Pax Romana, a period of relative internal peace and stability. Octavian became the most powerful man in the Roman world and the Senate bestowed upon him the honorific of Augustus in 27 BC. Octavian, now Augustus, became the first Roman emperor and transformed the republic into the Roman Empire.

Background

Mark Antony was in Egypt with Cleopatra instead of his wife, Octavia, Octavian‘s sister. Octavian was scheming to find a way to sever ties with Mark Antony, start a war to crush him, kill a potential rival and take control of the entire Roman world. He did this by cleverly exposing Antony’s will to the senate, where he read out how Antony had left all his money to his children by Cleopatra, where they would reign as monarchs over kingdoms that he and Cleopatra would leave to them. Romans were scandalized by this type of behavior. Then Antony divorced Octavia to marry Cleopatra.

Octavian convinced the senate via a propaganda campaign to start a war against Cleopatra, since they were reluctant to declare war on Antony, as he was a true Roman and the last thing Octavian or the senate needed was a mutiny. Eventually, Octavian chased Antony’s senatorial supporters from Rome, and in 32 BC, the Roman Senate declared war against Cleopatra.

Political and military buildup

The Caesariens, Octavian (Caesar’s principal, though not sole, heir), Antony, and Marcus Lepidus under the Second Triumvirate had stepped in to fill the power vacuum caused by Julius Caesar‘s assassination. After the triumvirate had defeated Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, and Lepidus was expelled from the triumvirate in 36 BC, Octavian and Antony were left as the two most powerful men in the Roman world. Octavian took control of the west, including Hispania, Gaul, Italia itself, and Africa. Antony received control of the east, including Graecia, Asia, Syria and Aegyptus.

For a time, Rome had peace. Octavian put down revolts in the west while Antony reorganized the east; however, the peace was short lived. Antony had been having an affair with the queen of Egypt, Cleopatra. Romans, especially Octavian, took note of Antony’s actions. Since 40 BC, Antony had been married to Octavia Minor, the sister of Octavian. Octavian seized the opportunity and had his minister Gaius Maecenas produce a propaganda campaign against Antony.

Nearly all Romans felt astonished when they heard word of Antony’s Donations of Alexandria. In these donations, Antony ceded much of Rome’s territory in the east to Cleopatra. Cleopatra and Caesarion were crowned co-rulers of Egypt and Cyprus; Alexander Helios was crowned ruler of Armenia, Media, and Parthia; Cleopatra Selene II was crowned ruler of Cyrenaica and Libya; and Ptolemy Philadelphus was crowned ruler of Phoenicia, Syria, and Cilicia. Cleopatra took the title of “queen of kings” and Caesarion took the title of “king of kings”.

In response, Octavian increased the personal attacks against Antony, but the senate and people of Rome were not convinced. Octavian’s chance came when Antony married Cleopatra in 32 BC before he divorced Octavia. That action combined with information that Antony was planning to establish a second senate in Alexandria created the perfect environment for Octavian to strip Antony of his power.

Octavian summoned the senate and accused Antony of anti-Roman sentiments. Octavian had illegally seized Antony’s will from the Temple of Vesta. In it, Antony recognized Caesarion as Caesar’s legal heir, left his possessions to his children by Cleopatra, and finally indicated his desire to be buried with Cleopatra in Alexandria instead of in Rome. The senators were not moved by Caesarion or Antony’s children but his desire to be buried outside Rome invoked the senate’s rage. Octavian blamed Cleopatra, not Antony. The senate declared war on Cleopatra, and Octavian knew that Antony would come to her aid.

When Cleopatra received word that Rome had declared war, Antony threw his support to Egypt. Immediately, the senate stripped Antony of all his official power and labeled him an outlaw and a traitor. However, 40% of the senate, along with both consuls, sided with Antony and left Rome for Greece. Octavian gathered all of his legions, numbering almost 200,000 Roman legionaries. Cleopatra and Antony did so too, assembling roughly the same number in mixed heavy Roman and light Egyptian infantry.

History

War

Naval theatre

By mid-31 BC, Antony maneuvered his army into Greece and Octavian soon followed. Octavian brought with him his chief military adviser and closest friend Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa to command his naval forces. Although the ground forces were comparable, Octavian’s fleet was superior in number. Antony’s fleet was made up of large vessels, but with inexperienced crews and commanders. Octavian’s fleet of smaller, more maneuverable vessels was filled with experienced sailors.

Octavian moved his soldiers across the Adriatic Sea to confront Antony near Actium. Meanwhile, Agrippa disrupted Antony’s supply lines with the navy. Gaius Sosius commanded a squadron in Antony’s fleet with which he managed to defeat the squadron of Lucius Arruntius and put it to flight, but when the latter was reinforced by Agrippa, Sosius’s ally Tarcondimotus I – the king of Cilicia – was killed and Sosius himself was forced to flee.

Octavian decided not to attack and risk unnecessary losses. Instead, Octavian wanted to battle Antony by sea where his experienced sailors could dominate. In response, Antony and Octavian engaged in Fabian strategy until the time was right. As the summer ended and autumn began to set in, both Octavian and Antony settled for a battle of attrition. The strategy of delay paid dividends to Octavian, as morale sank and prominent Romans deserted Antony’s cause. However, despite this, Antony was still able to maintain the loyalty of his legions.

The first conflict of the war occurred when Octavian’s general Agrippa captured the Greek city and naval port of Methone. The city had previously been loyal to Antony. The fighting had been brutal but in the end Agrippa’s hit and run tactics were successful. On the contrary, Antony’s veteran cavalry won most of the skirmishes on land. Although Antony was an experienced soldier, he did not understand naval combat, which led to his downfall. Antony moved his fleet to Actium, where Octavian’s navy and army had taken camp. The stage was set for one of the largest naval battles of all time, with Antony bringing 290 ships in addition to between 30 and 50 transports. Octavian had 350 ships. Antony’s ships were much larger and better armed. In what would become known as the Battle of Actium, Antony, on September 2, 31 BC, moved his large quinqueremes through the strait and into the open sea. There, Octavian’s light and manoeuvrable Liburnian ships drew in battle formation against Antony’s warships. Cleopatra stayed behind Antony’s line on her royal barge.

A devastating blow to Antony’s forces came when one of Antony’s former generals delivered Antony’s battle plan to Octavian. Antony had hoped to use his biggest ships to drive back Agrippa’s wing on the north end of his line, but Octavian’s entire fleet stayed carefully out of range. Shortly after mid-day, Antony was forced to extend his line out from the protection of the shore, and then finally engage the enemy. Octavian’s fleet, armed with better trained and fresher crews, made quick work of Antony’s larger and less experienced navy. Octavian’s soldiers had spent years fighting in Roman naval combat, where one objective was to ram the enemy ship and at the same time kill the above deck crew with a shower of arrows and catapult-launched stones large enough to decapitate a man.

As the armies stood on either side of the naval battle, they watched as Antony was being outmatched by Agrippa. Seeing that the battle was going against Antony, Cleopatra decided to follow Antony’s original orders and took her squadron of ships and tried to penetrate Octavian’s centre. As a gap opened in Agrippa’s blockade, she funneled through, Antony then issued orders for his entire fleet to breakthrough Octavian’s lines. Antony led the breakthrough and his spearhead was able to penetrate Octavian’s centre. However, shortly after Antony’s break through, Agrippa ordered his flanks to attack the rest of Antony’s ships from both sides. Antony and Cleopatra could only watch on helplessly as their fleet – once the largest in Roman history – was destroyed. By the end of the day, almost Antony’s entire fleet lay at the bottom of the sea and the Roman world witnessed the largest naval battle in almost 200 years. The couple was forced to take their remaining 90 ships and retreat to Alexandria. Upon seeing the destruction of Antony’s fleet his legions decided that they would try to meet up with him, however, after losing control of the sea, supplies for Antony’s legions ran thin. After a week the commanders of Antony’s land forces, which were supposed to follow him to Asia, promptly surrendered their legions without a fight.

Land campaign

Even though Octavian wanted to immediately pursue Antony and Cleopatra, many of his veterans wanted to retire and return to private life. Octavian allowed many of his longest serving veterans (as many as 10 legions by some accounts) to retire. Many of those legionaries could trace their service to Julius Caesar some 20 years earlier.

After the winter ended, Octavian resumed the hunt. In early 30 BC, Octavian rejected the idea of transporting his army across the sea and attacking Alexandria directly, and instead travelled by land through Asia. Antony had received much of his backing from Rome’s client kingdoms in the east. By marching his army by land, Octavian ensured Antony could not regroup and cement his authority over the provinces.

The majority of Antony’s army, 23 legions plus 15,000 cavalry, had been left in Greece after Actium where, eventually, without supplies, they surrendered. Meanwhile, Antony attempted to secure an army in Cyrenaica from Lucius Pinarius. Unfortunately for Antony, Pinarius had switched his loyalty to Octavian. When Octavian received word of this development, he ordered Pinarius to move his four legions east towards Alexandria while Octavian would move west. Trapped in Egypt with the remnant of their former army, Antony and Cleopatra bided their time awaiting Octavian’s arrival.

When Octavian and Pinarius arrived at Alexandria, they placed the entire city under siege. Before Octavian had arrived, Antony took the roughly 30,000 soldiers he had left and attacked Pinarius, unaware that he was outnumbered two to one. Pinarius destroyed what was left of Antony’s army with Antony escaping back to Alexandria before Octavian arrived. As Octavian approached with his legions, what remained of Antony’s cavalry and fleet surrendered to him. Most of the remainder of Antony’s infantry surrendered without any engagement at this stage of the conflict, and Antony’s cause was lost.

Antony was forced to watch as his army and hopes of dominance in Rome were handed to Octavian. In honourable Roman tradition, Antony, on August 1, 30 BC, fell on his sword. According to the ancient accounts however, he was not entirely successful and with an open wound in his belly, was taken to join Cleopatra, who had fled to her mausoleum. Here Antony succumbed to his wound and supposedly died in his lover’s arms, leaving her alone to face Octavian.

Cleopatra did not immediately follow Antony in suicide. Instead, in a final effort to save her position and her children, Cleopatra opened negotiations with Octavian. Cleopatra begged Octavian to spare Caesarion’s life in exchange for his willing imprisonment. Octavian refused, supposedly saying “two Caesars are one too many,” as he ordered Caesarion’s death.[6] Subsequently, Caesarion was “butchered without compunction”. Within that same week, Octavian also informed Cleopatra that she was to play a role in his triumph back in Rome, a role that was “carefully explained to her”. According to Strabo, who was alive at the time of the event, Cleopatra died from a self-induced bite from a venomous snake, or from applying a poisonous ointment to herself.[7] Learning of Cleopatra’s death, Octavian had mixed feelings. He admired the bravery of Cleopatra, and gave her and Antony a public military funeral in Rome. The funeral was grand and a few of Antony’s legions even marched alongside the tomb. A day of mourning throughout Rome was enacted. This was partly due to Octavian’s respect for Antony and partly because it further helped show the Roman people how benevolent Octavian was. As they left Alexandria, a new age dawned when Rome annexed Egypt. With Cleopatra’s death, the final war of the republic was over.

Aftermath

Within a month, Octavian was named pharaoh, and Egypt became his personal possession. By executing Antony’s supporters, Octavian finally brought a century of civil war to a close. In 27 BC Octavian was named Augustus by the senate and given unprecedented powers. Octavian, now Augustus, transformed the republic into the Roman Empire, ruling it as the first Roman emperor.

In the ensuing months and years, Augustus passed a series of laws that, while outwardly preserving the appearance of the republic, made his position within it of paramount power and authority. He laid the foundations for what is now called the Roman Empire. From then on, the Roman state would be ruled by a princeps (first citizen); in modern terms, Rome would from now on be ruled by emperors.

The senate ostensibly still had power and authority over certain senatorial provinces, but the critical border provinces, such as Syria, Egypt, and Gaul, requiring the greatest numbers of legions, would be directly ruled by Augustus and succeeding emperors.

With the end of the last republican civil war, the republic was replaced by the empire. The reign of Augustus would usher in the golden era of Roman culture and produce a stability which Rome had not seen in over a century. With Rome in control of the entire Mediterranean world, a peace would reign in the Roman world for centuries after the death of Augustus: the so-called Pax Romana (Roman Peace).

Three of the Roman emperors in the 1st century, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero, were direct descendants of Antony.

The empire that Augustus established would last in Western Europe until the fall of Rome in the 5th century AD. The eastern part of the Roman Empire would also survive as the Byzantine Empire until the fall of Constantinople in AD 1453.

Plans underway to put Robert E. Lee monument back on display

Default Mono Sans Mono Serif Sans Serif Comic Fancy Small CapsDefault X-Small Small Medium Large X-Large XX-LargeDefault Outline Dark Outline Light Outline Dark Bold Outline Light Bold Shadow Dark Shadow Light Shadow Dark Bold Shadow Light BoldDefault Black Silver Gray White Maroon Red Purple Fuchsia Green Lime Olive Yellow Navy Blue Teal Aqua OrangeDefault 100% 75% 50% 25% 0%Default Black Silver Gray White Maroon Red Purple Fuchsia Green Lime Olive Yellow Navy Blue Teal Aqua OrangeDefault 100% 75% 50% 25% 0%The American Heritage Association says the Robert E. Lee monument, which was taken down in 2021, will be put back up on public display in Charleston County.

Published: Jul. 29, 2025 at 1:06 PM PDT|Updated: Jul. 30, 2025 at 1:48 AM PDT

CHARLESTON, S.C. (WCSC) – The American Heritage Association says the Robert E. Lee monument, which was taken down in 2021, will be put back up on public display in Charleston County.

The monument will be re-erected in a “more prominent location within the city of Charleston,” AHA President Brett Barry said in a release Tuesday.

“President Trump has provided Americans an opportunity to turn the tide in the historical monument debate, and we are succeeding,” Barry said.

The Charleston County School Board, which removed the monument from the School of Math and Science, played no role in securing the new location and its chairman remained combative throughout the process, the AHA said in a release.

The association filed a lawsuit against the Charleston County School Board in 2021.

South Carolina Attorney General Alan Wilson said in 2022 that the monument’s removal violated the state’s Heritage Act, the group said.

The Heritage Act is a law that protects some state monuments, markers or memorials from being removed without legislative approval.

The lawsuit was scheduled to be heard in court on Wednesday, but the AHA withdrew the suit after the judge set to preside over the case, Judge Jennifer McCoy, ruled in a different case that only the state’s attorney general can enforce the Heritage Act.

By —

Share on FacebookShare on Twitter

Robert E. Lee opposed Confederate monuments

Nation Aug 15, 2017 1:55 PM EDT

At the center of the “Unite the Right” rally that turned deadly in Charlottesville last weekend was a protest of the city’s plan to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee. White supremacists, neo-Nazis and others have made monuments to the Confederate commanding general a flashpoint — at times marching to keep them standing.

But Lee himself never wanted such monuments built.

“I think it wiser,” the retired military leader wrote about a proposed Gettysburg memorial in 1869, “…not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, to commit to oblivion the feelings engendered.”

WATCH:The shifting history of Confederate monuments

Lee died in 1870, just five years after the Civil War ended, contributing to his rise as a romantic symbol of the “lost cause” for some white southerners.

But while he was alive, Lee stressed his belief that the country should move past the war. He swore allegiance to the Union and publicly decried southern separatism, whether militant or symbolic.

“It’s often forgotten that Lee himself, after the Civil War, opposed monuments, specifically Confederate war monuments.”

“It’s often forgotten that Lee himself, after the Civil War, opposed monuments, specifically Confederate war monuments,” said Jonathan Horn, the author of the Lee biography, “The Man Who Would Not Be Washington.”

In his writings, Lee cited multiple reasons for opposing such monuments, questioning the cost of a potential Stonewall Jackson monument, for example. But underlying it all was one rationale: That the war had ended, and the South needed to move on and avoid more upheaval.

“As regards the erection of such a monument as is contemplated,” Lee wrote of an 1866 proposal, “my conviction is, that however grateful it would be to the feelings of the South, the attempt in the present condition of the Country, would have the effect of retarding, instead of accelerating its accomplishment; [and] of continuing, if not adding to, the difficulties under which the Southern people labour.”

The retired Confederate leader, a West Point graduate, was influenced by his knowledge of history.

“Lee believed countries that erased visible signs of civil war recovered from conflicts quicker,” Horn said. “He was worried that by keeping these symbols alive, it would keep the divisions alive.”

Construction crews prepare a monument of Robert E. Lee, who was a general in the Confederate Army, for removal in New Orleans, Louisiana on May 19, 2017. Photo by REUTERS/Jonathan Bachman

Lee himself was conflicted about the core issues of his day. He was a slave owner who some say was cruel and a general who fought to preserve the institution. But he personally described slavery as a “moral and political evil” that should end. Before the war, Lee opposed secession, but once his native Virginia voted to leave the Union he declared he was honor-bound to fight for the Confederacy.

Academics and writers vigorously debate his sentiments and strengths, but historians seem to agree on Lee’s views about memorials.

“He said he was not interested in any monuments to him or – as I recollect – to the Confederacy,” explained James Cobb, history professor emeritus at the University of Georgia, who has written about Lee’s rise as an icon.

“I don’t think that means he would have felt good about the people who fought for the Confederacy being completely forgotten,” Cobb added. “But he didn’t want a cult of personality for the South.”

Lee advocated protection of just one form of memorial: headstones in cemeteries.

“All I think that can now be done,” he wrote in 1866, “is … to protect the graves [and] mark the last resting places of those who have fallen…”

Would Lee have opposed his own monument today? Horn leaned toward yes, though he noted that it’s impossible to compare Lee’s views in the 1860s with the situation today.

“You think he’d come down in the camp that would say ‘remove the monuments,’” Horn posited. “But you have to ask why [he would remove them]. He might just want to hide the history, to move on, rather than face these issues.”

John Hyrcanus (/hɜːrˈkeɪnəs/; Hebrew: יוחנן הרקנוס, romanized: Yoḥānān Hurqanos; Koine Greek: Ἰωάννης Ὑρκανός, romanized: Iōánnēs Hurkanós) was a Hasmonean (Maccabean) leader and Jewish High Priest of Israel of the 2nd century BCE (born 164 BCE, reigned from 134 BCE until he died in 104 BCE). In rabbinic literature he is often referred to as Yoḥanan Cohen Gadol (יוחנן כהן גדול), “John the High Priest”.[a]

Name

Josephus explains in The Jewish War that John was also known as “Hyrcanus” but does not explain the reason behind this name. The only other primary sources—the Books of the Maccabees—never used this name for John. The single occurrence of the name Hyrcanus in 2 Maccabees 3:11 refers to a man to whom some of the money in the Temple belonged during the c. 178 BCE visit of Heliodorus.[1]

The reason for the name is disputed amongst biblical scholars, with a variety of reasons proposed:

- Familial origin in the region of Hyrcania on the Caspian Sea[2]

- A Greek regnal name, which would have represented closer ties with the Hellenistic culture against which the Maccabees had revolted under Seleucid rule. However, the region of Hyrcania had been conquered by Mithridates I of Parthia in 141–139 BCE

- Given the name by the Seleucids after he fought in the region alongside Antiochus VII Sidetes against Phraates II of Parthia in 130–129 BCE, a campaign which resulted in the release of Antiochus’ brother Demetrius II Nicator from captivity in Hyrcania

Life and work

He was the son of Simon Thassi and hence the nephew of Judas Maccabeus, Jonathan Apphus and their siblings, whose story is told in the deuterocanonical books of 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees, in the Talmud, and in Josephus. John was not present at a banquet at which his father and his two brothers were murdered by John’s brother-in-law, Ptolemy son of Abubus. He attained his father’s former offices of High Priest and ethnarch, but not king.[3] Josephus said that John Hyrcanus had five sons but he named only four in his histories: Judah Aristobulus I, Antigonus I, Alexander Jannai, and Absalom. It is the fifth brother who is said to have unsuccessfully sought the throne at the death of Aristobulus I according to Antiquities of the Jews 13.12.1.

Siege of Jerusalem

During the first year of John Hyrcanus’s reign, he faced a serious challenge to Judean independence from the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus VII Sidetes marched into Judea, pillaged the countryside, and laid what became a year-long siege of Jerusalem. The prolonged siege caused Hyrcanus to remove any Judean from the city who could not assist with the defence effort (Antiquities 13.240). These refugees were not allowed to pass through Antiochus’ lines, becoming trapped in the middle of a chaotic siege. Facing a humanitarian crisis, Hyrcanus re-admitted his estranged Jerusalemites when the festival of Sukkot arrived. Then, as food shortages in Jerusalem became severe, Hyrcanus negotiated a truce with Antiochus.[4]

The terms of the truce required payment of 3,000 talents of silver to Antiochus, the dismantling of the walls of Jerusalem, Judean participation in the Seleucid war against the Parthians, and renewed Judean recognition of Seleucid control (Antiquities 13.245). These terms were a harsh blow to Hyrcanus, who had to loot the tomb of David to pay the 3,000 talents (The Wars of the Jews I 2:5).

Under Seleucid control (133–128 BCE)

Following the Seleucid siege, Judea faced tough economic times which were magnified by taxes to the Seleucids enforced by Antiochus. Furthermore, Hyrcanus was forced to accompany Antiochus on his eastern campaign in 130 BCE. Hyrcanus probably functioned as the military commander of a Jewish company in the campaign.[5] It is reported that Antiochus, out of consideration for the religion of his Jewish allies, at one point ordered a two days’ halt of the entire army to allow them to avoid breaking the Sabbath and the festival of Shavuot.[6]

This enforced absence probably caused a loss of support for the inexperienced Hyrcanus among the Judean population.[7] Judeans in the countryside were especially disillusioned with Hyrcanus after Antiochus’ army plundered their land. John Hyrcanus’s expulsion of the non-military population of Jerusalem during the siege had probably caused resentment, and his looting of the Tomb of David violated his obligations as High Priest, which would have offended the religious leadership.[8]

Therefore, at an early point in his 31-year reign, Hyrcanus had lost support from Judeans in various cultural sectors. The Jerusalemites, the rural Judeans, and the religious leadership probably doubted the future of Judea under Hyrcanus. However in 128 BCE Antiochus VII was killed in battle against Parthia. What followed was an era of conquest led by Hyrcanus that marked the high point of Judea as the most significant power in the Levant.[9]

Conquests

situation in 134 BCE area conquered

John Hyrcanus took advantage of unrest in the Seleucid Empire to reassert Judean independence and acquire new territories. In 130 BCE Demetrius II, the former Seleucid king, returned from exile in Hyrcania to resume the government of his empire. However the transition of power made it difficult for Demetrius to reassert control over Judea.,[10] and the Seleucid Empire also lost control of other principalities. The Ituraeans of Lebanon, the Ammonites of the Transjordan, and the Arabian Nabateans were among these.[11] Hyrcanus determined to take advantage of the dissipation of the Seleucid Empire to enlarge the Judean State.

Hyrcanus raised a new mercenary army that differed from the Judean forces that had been defeated by Antiochus VII (Ant.13.249). The Judean population was probably still recovering from the attack of Antiochus, and therefore could not provide enough able men for a new army.[10] The new army was funded with more treasure that Hyrcanus removed from the Tomb of David.[12]

Beginning in 113 BCE, Hyrcanus began an extensive military campaign against Samaria. Hyrcanus placed his sons Antigonus and Aristobulus in charge of the siege of Samaria. The Samaritans called for help and eventually received 6,000 troops from Antiochus IX Cyzicenus. Although the siege lasted for a long, difficult year, Hyrcanus did not give up. Ultimately Samaria was overrun and devastated. Cyzicenus’ mercenary army was defeated and the city of Scythopolis seems to have been occupied by Hyrcanus as well.[13] The inhabitants of Samaria were enslaved. Upon conquering former Seleucid regions Hyrcanus implemented a policy of compelling the non-Jewish populations to adopt Jewish customs.[14][15]

John Hyrcanus’s first conquest was an invasion of the Transjordan in 110 BCE.[16] John Hyrcanus’s mercenary army laid siege to the city of Medeba and took it after a six-month siege. After these victories, Hyrcanus went north towards Shechem and Mount Gerizim. The city of Shechem was reduced to a village and the Samaritan Temple on Mount Gerizim was destroyed.[14] This military action against Shechem has been dated archaeologically around 111–110 BCE.[17] Destroying the Samaritan Temple on Mount Gerizim helped ameliorate John Hyrcanus’s standing among religious elite and common Jews who detested any temple to God outside of Jerusalem.

Hyrcanus also initiated a military campaign against the Idumeans (Edomites). During this campaign Hyrcanus conquered Adora, Maresha and other Idumean towns (Ant.13.257). Hyrcanus then instituted forced conversions of the Idumeans to Judaism.[18] This was an unprecedented measure for a Judean ruler; it was the first instance of forced conversion perpetrated by Jews in recorded history.[19] However, some scholars dispute the narrative of forced conversion and believe that the Edomites peacefully assimilated in Judean society.[20]

Economy, foreign relations, and religion

After the siege of Jerusalem, Hyrcanus faced a serious economic crisis in Judea, although the economic difficulties probably subsided after the death of Antiochus VII, since Hyrcanus no longer had to pay taxes or tributes to a weaker Seleucid Empire.[21] The economic situation eventually improved enough for Hyrcanus to issue his own coinage (see below). On top of that, Hyrcanus initiated vital building projects in Judea. Hyrcanus re-built the walls destroyed by Antiochus. He also built a fortress north of the Temple called the Baris and possibly also the fortress Hyrcania.[22]

Moreover, out of desperation, Hyrcanus sought for good relations with the surrounding Gentile powers, especially the growing Roman Republic. Two decrees were passed in the Roman Senate that established a treaty of friendship with Judea.[23] Although it is difficult to specifically date these resolutions, they represent efforts made between Hyrcanus and Rome to maintain stable relations. Also, an embassy sent by Hyrcanus received Roman confirmation of Hasmonean independence.[24] Hyrcanus was an excellent case of a ruler backed by Roman support.

In addition to Rome, Hyrcanus was able to maintain steady relations with Ptolemaic Egypt. This was probably made possible due to various Jews living in Egypt who had connections with the Ptolemaic Court (Ant. 13.284–287). Finally, the cities of Athens and Pergamon even showed honor to Hyrcanus in an effort to appease Rome.[25]

Furthermore, the minting of coins by Hyrcanus demonstrates John Hyrcanus’s willingness to delegate power. Sixty-three coins found near Bethlehem bear the inscription, “Yohanan the High Priest.” The reserve side of the coins contains the phrase, “The Assembly of the Jews.” This seems to suggest that during his reign, Hyrcanus was not an absolute ruler. Instead, Hyrcanus had to submit at times to an assembly of Jews that had a certain amount of minority power.[26] The coins lack any depictions of animals or humans. This suggests that Hyrcanus strictly followed the Jewish prohibition against graven images. The coins also seem to suggest that Hyrcanus considered himself to be primarily the High Priest of Judea, and his rule of Judea was shared with the Assembly.[27]

In Judea, religious issues were a core aspect of domestic policy. Josephus only reports one specific conflict between Hyrcanus and the Pharisees, who asked him to relinquish the position of High Priest (Ant. 13.288–296).[28] After this falling-out, Hyrcanus sided with the rivals of the Pharisees, the Sadducees. However, elsewhere Josephus reports that the Pharisees did not grow to power until the reign of Queen Salome Alexandra (JW.1.110) The coins minted under Hyrcanus suggest that Hyrcanus did not have complete secular authority. Furthermore, this account may represent a piece of Pharisaic apologetics due to Josephus’s Pharisaic background.[29] Regardless, there were probably tensions because of the religious and secular leadership roles held by Hyrcanus.

Ultimately, one of the final acts of John Hyrcanus’s life was an act that solved any kind of dispute over his role as High Priest and ethnarch. In the will of Hyrcanus, he provisioned for the division of the high priesthood from secular authority. John Hyrcanus’s widow was given control of civil authority after his death, and his son Judas Aristobulus was given the role of High Priest. This action represented John Hyrcanus’s willingness to compromise over the issue of secular and religious authority.[30] (However, Aristobulus was not satisfied with this arrangement, so he cast his mother into prison and let her starve.)

The Tomb of Hyrcanus was, according to Josephus, located near the Towers’ Pool (also known as Hezekiah’s Pool) northwest of the present Jaffa Gate.[31] During the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE, Titus selected the area opposite the tomb to begin his assault on the city’s third wall.[31]

Legacy

John Hyrcanus the High Priest is remembered in rabbinic literature as having made several outstanding enactments and deeds worthy of memorial, one of which being that he cancelled the requirement of saying the avowal mentioned in Deuteronomy 26:12–15 once in every three years, since he saw that in Israel they had ceased to separate the First Tithe in its proper manner and which, by making the avowal, and saying “I have hearkened to the voice of the Lord my God, and have done according to all that you have commanded me,” he makes himself dishonest before his Maker and liable to God’s wrath.[32] In his days, the First Tithe, which was meant to be given unto the Levites, was given instead to the priests of Aaron’s lineage, after Ezra had fined the Levites for not returning in full force to the Land of Israel. By not being able to give the First Tithe unto the Levites, as originally commanded by God, this made the avowal null and void.[33] In addition, John Hyrcanus is remembered for having cancelled the reading of Psalm 44:23, formerly chanted daily by the Levites in the Temple precincts, and which words, “Awake! Why do you sleep, O Lord?, etc.”, seemed inappropriate, as if they were imposing their own will over God’s, or that God was actually sleeping.[34] In similar fashion, the High Priest cancelled an ill-practice had by the people to cause bleeding near the eyes of sacrificial calves by beating their heads so as to stun them, prior to their being bound and slaughtered, since by beating the animal in such a way they ran the risk of causing a blemish in the animal’s membrane lining its brain.[35] To prevent this from happening, the High Priest made rings in the ground of the Temple court for helping to secure the animals before slaughter.

Before John Hyrcanus officiated as Israel’s High Priest, the people had it as a practice to do manual work on the intermediate days of the Jewish holidays, and one could hear in Jerusalem the hammer pounding against the anvil. The High Priest passed an edict restricting such labours on those days, thinking it inappropriate to do servile work on the Hol ha-Moed, until after the Feast (Yom Tov). It had also been a custom in Israel, since the days that the Hasmoneans defeated the Grecians who prevented them from mentioning the name of God in heaven, to inscribe the name of God in their ordinary contracts, bills of sale and promissory notes. They would write, for example, “In the year such and such of Yohanan, the High Priest of the Most High God.” But when the Sages of Israel became sensible of the fact that such ordinary contracts were often discarded in the rubbish after reimbursement, it was deemed improper to show disrespect to God’s name by doing so. Therefore, on the 3rd day of the lunar month Tishri, the practice of writing God’s name in ordinary contracts was cancelled altogether, while the date of such cancellation was declared a day of rejoicing, and inscribed in the Scroll of Fasting.[36]

The Mishnah (Parah 3:4[5]) also relates that during the tenure of John Hyrcanus as High Priesthood, he had prepared the ashes of two Red heifers used in purifying those who had contracted corpse uncleanness.[37]

In what is seen as yet another one of John Hyrcanus’s accomplishments, during his days any commoner or rustic could be trusted in what concerns Demai-produce (that is, if a doubt arose over whether or not such produce bought from him had been correctly divested of its tithes), since even the common folk in Israel were careful to separate the Terumah-offering given to the priests. Still, such produce required its buyer to separate the First and Second Tithes.[38] Some view this as also being a discredit unto the High Priest, seeing that the commoners refused to separate these latter tithes because of being intimidated by bullies, who took these tithes from the public treasuries by force, while John Hyrcanus refused to censure such bad conduct.[39]

In the later years of his life, John Hyrcanus abandoned the sect of the Pharisees and joined the Sadducees. This prompted the famous rabbinic dictum: “Do not believe in yourself until your dying day.”[40] At his death, a monument (Hebrew: נפשיה דיוחנן כהן גדול) was built in his honour and where his bones were interred. The monument was located in what was outside the walls of the city at that time, but by Josephus‘ time was between the second[b] and third[c] walls of Jerusalem, and where the Romans had built a bank of earthworks to break into the newer third wall encompassing the upper city, directly opposite John’s monument.[41]

Leave a comment