Barger reading his telegram to LBJ. (*Although it’s often suggested that he spelled ‘guerrilla’ as ‘gorilla

Putin met Trump eight years ago. Did Putin suggest to the newly elected President his political life would be much better – IF there was only ONE PARTY? How many Republican Voters understand Governor Abbot made……PUTIN VERY HAPPY?

When I was young, if it appeared you were for THE RUSSIANS, you were labeled a Communist! If you protested against the Vietnam War that was funded by Russia, the Hell’s Angels would beat you up.

Half the people you see walking in the same street as you, will be overjoyed the last Democrat that ran for President was – A BLACK WOMAN BORN IN OAKLAND – the first home of the Angels? Will Kamala Harris’s history be erased because it is BLACK HISTORY?

Why do Black People dislike, even – HATE PUTIN? With one party – does it really matter anymore?

What if I changed the tone of this blog, and was all for President Trump and his ideas? Would it matter?……..NO! Why?

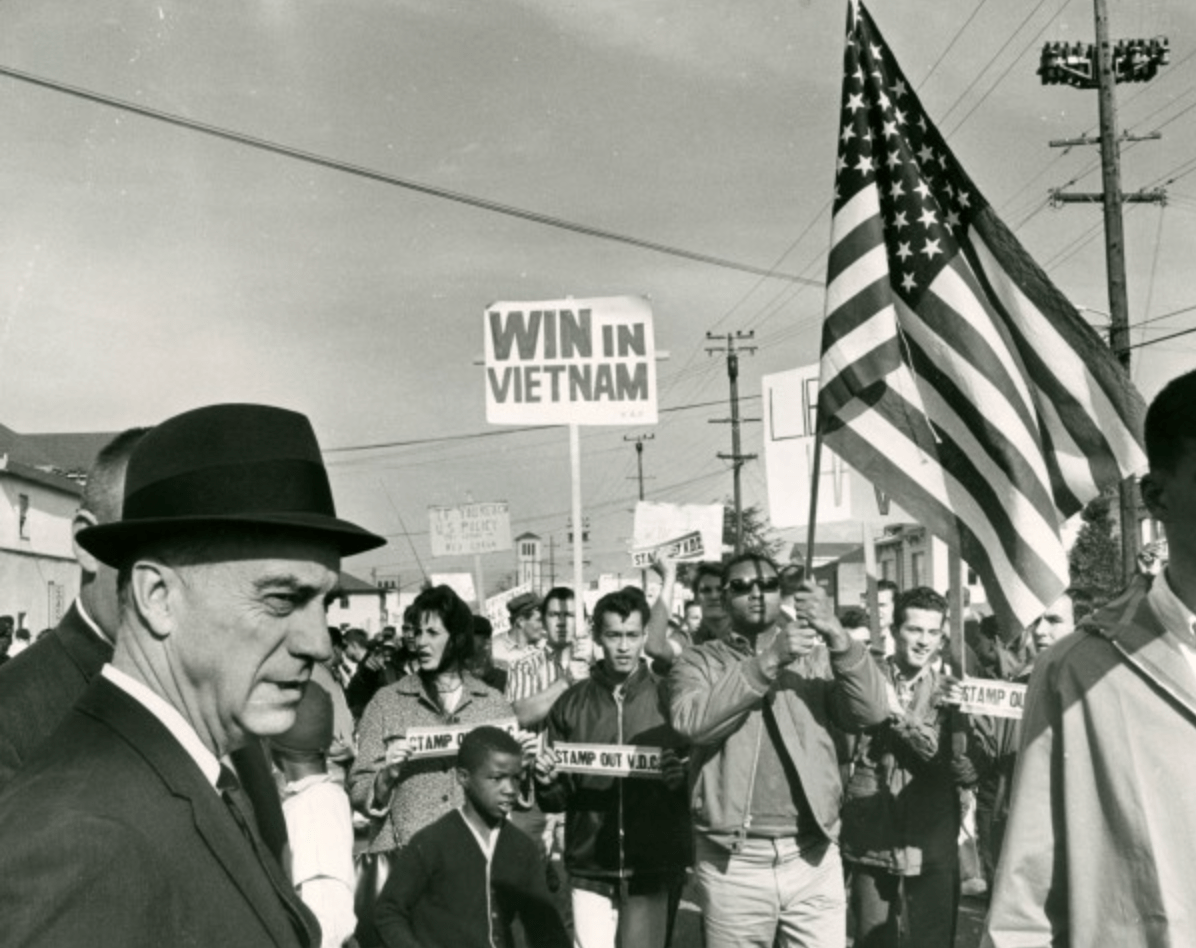

In 1965 the Hell’s Angels beat up Antiwar Protestors, then wrote a letter to the President saying they are LOYAL PATRIOTS! They used Americans execising Freedom of Speech, to get – PUBLICITY – like the three men below. Heres The Question……Does Putin, and Trump really believe the Democrats

STOLE THE ELECTION?

How about the three men below? Are these Election Deniers going along with THE LIE, knowing the President of Russia wants only ONE PARTY to rule America? Are not they doing the bIdding of

THE DICATOR OF RUSSIA?

John Presco

Credit: Al Drago/Pool via AP

Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and Vice President JD Vance, with National Guard at Union Station.

The Russian Federation has a de jure multi-party system, however it operates as a dominant-party system. As of 2020, six parties have members in the federal parliament, the State Duma, with one dominant party (United Russia). As of July 2023, 27 political parties[1] are officially registered in the Russian Federation, 25 of which have the right to participate in elections.[2]

Lately, I’ve been thinking about an incident that happened in 1965, seven years before I was born. It centered on an antiwar protest in Berkeley, one of the first of countless such protests to come. Though just a blip in the grand scheme of Vietnam era turmoil, it seems to point to something important about America and the nature of patriotism.

It starts with a guy named “Tiny.” Tiny was 6’7″ and 300 pounds. And he really liked to fight.

He was first into the breach that fall afternoon in 1965, punching his way through the front of the seven-block-long peace march on Adeline Street, near the Berkeley–Oakland border. Tiny was a member of the outlaw motorcycle gang Hells Angels, and more than a dozen of his brothers followed in his wake, ripping down antiwar signs and screaming, “Go back to Russia, you fucking Communists!”

By the time things calmed down, six Angels were in custody—including Tiny, who took a nightstick to the skull and on his way to the pavement broke a cop’s leg.

Later, the Angels held a press conference at their bail bondsman’s office. Oakland chapter leader Ralph “Sonny” Barger, an Army vet with slicked-back hair and an air of casual menace, called the protesters a “mob of traitors.” The Angels would take the high road, however, and absent themselves from future protests because, Barger explained, “Our patriotic concern for what these people are doing to our great nation may provoke violence by us.” Then he read a telegram he claimed to have sent to President Lyndon Johnson, volunteering the Angels for behind-the-lines “gorrilla” [sic] duty in Vietnam.

The Angels, at first blush, seemed unlikely patriots. Though not yet well known, they had a reputation with law enforcement for drinking, smoking dope, and sacking towns like modern-day Visigoths, answering to no authority higher than their East Oakland clubhouse. But now there they were, waving the flag. Their form of patriotism was gut-level, atavistic, loyalty to nation through blood and fire. Their group persona, meanwhile, was the stuff of American mythology, a grab-bag of frontier clichés sprung to life—they were contemporary cowboys, John Wayne’s unwashed, scofflaw cousins.

From behind the police lines, Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, who would publish a book on the Angels in 1967, watched the melee unfold that day. He noted that the antiwar crowd was fascinated by the bikers’ “aggressive, antisocial stance” and had hoped they might be allies in the struggle. Instead, “When push came to shove, the Hells Angels lined up solidly with the cops, the Pentagon, and the John Birch Society.”

At that point in the war, the American public tended to side with the Angels—at least when it came to the protesters. After the march, the counterculture newspaper Berkeley Barb canvassed Oaklanders’ opinions. Only 5 out of 66 surveyed supported the marchers. One woman said, “I think they should take a machine gun and shoot them all down.”

Ultimately, the protesters were on the right side of history. As American involvement in Vietnam deepened and the death toll mounted, public opinion turned decisively against a conflict that looked more unwinnable by the day.

Dissent often looks more admirable in the rear-view mirror. While some of the marchers likely had nothing more principled on their minds than avoiding the draft or getting laid, plenty of others could have articulated the politics behind their protest, connecting it not just to Marxist theories like those of foreign anticolonialists such as Frantz Fanon, but also to the Enlightenment ideals espoused by homegrown pot-stirrers such as Thomas Paine. They didn’t see their protest as unpatriotic. It was more an expression of idealism. As Cal’s Vietnam Day Committee announced that spring, “The problem of Vietnam is the problem of the soul of America.”

Martin Luther King, too, spoke of Vietnam in those terms, in a famous 1967 speech in which the civil rights leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner publicly spoke out against the war. “If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned,” King told his audience, “part of the autopsy must read: Vietnam.” King also reminded his listeners that the motto of his Southern Christian Leadership Conference was “To save the soul of America.”

As UC Berkeley linguist and NPR commentator Geoffrey Nunberg notes, “To describe oneself as a patriot is to suggest that others are less so.”

A half-century on, the question of who and what defines the soul of America (and whether it needs saving) and what it means to be a patriot is as unsettled as ever. This is mostly due to the quicksilver nature of the term patriotism itself. Patriotism lives primarily in the realm of myth and symbol, changeable from Left to Right and from one era to another. JFK and George W. Bush, civil rights leaders and Tea Partiers—patriots all, depending on whom you ask.

Jack Citrin, a professor of political science at Berkeley who has studied the relationship between American multiculturalism and patriotism, points out that the word is easy enough to define: love of country. The real question, though, is What do you mean when you say it?

“It was always interesting to see the fights between liberals and conservatives,” says journalist Paul Krassner, the former Yippie and Merry Prankster, who covered the anti-Vietnam movement in his underground newspaper The Realist. “Each group would shout at the other group, ‘We’re the patriots! You’re being unpatriotic!’”

As Berkeley linguist and NPR commentator Geoffrey Nunberg notes, “To describe oneself as a patriot is to suggest that others are less so.”

It’s not always a matter of rhetoric. Iconography also comes into play. In the sixties, symbols of patriotism were everywhere, useful proxies for anyone who wanted to make a statement on Vietnam. War supporters flew flags on their porches, and Richard Nixon donned a flag lapel pin. (According to biographer Stephen Ambrose, Nixon got the idea from Robert Redford’s antiestablishment film, The Candidate.) Protesters waved the flag, too—and wore it, sporting the stars and stripes on bell-bottoms and miniskirts and fringed jackets. Yippie Abbie Hoffman made a shirt out of Old Glory, and others painted it on their guitars, à la Wayne Kramer of the Detroit proto-punks MC5. While Jimi Hendrix played a tortured rock rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” pro-war crowds sang “God Bless America.”

As the war ground on, however, the sense of frustration on the Left grew. Anger at the war bled into a generalized anger at the country. Liberals quit waving the flag. Krassner says, “You felt ashamed to be an American.”

By the time the last chopper lifted off the U.S. Embassy roof in Saigon, the Left was in full retreat from patriotism, leaving the Right to define the concept as it saw fit. The Right’s version tended to draw from the cowboy mythos of rugged individualism, just as the Angels’ version did. It was also militaristic, celebrating both American military power and the American soldier. Finally, the Right embraced a brand of American exceptionalism rooted in the Pilgrims’ Calvinist beliefs—Ronald Reagan’s invocation of America as a “shining city upon a hill,” blessed by Providence. A beacon to the world.

That exceptionalism finds expression on the Left as well, often as part of an ethic of global service, exemplified by programs such as the Peace Corps. Two decades earlier, President John F. Kennedy had invoked the same image before reminding his audience—the Massachusetts legislature—that, “of those to whom much is given, much is required.” In 2006, so did Barack Obama, when addressing the graduating class at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Perhaps the truest thing anyone can say of patriotism is that it’s personal. I came of political age in the Reagan era, and in the hardcore punk scene that grew in response to it. I devoured righteous broadsides on apartheid, the prison-industrial complex, and Salvadoran death squads in Maximum Rocknroll, the Bay Area punk bible. I listened to bands with gleefully provocative names—Jodie Foster’s Army, Millions of Dead Cops, Dead Kennedys.

The longtime leader of the Hells Angels, Ralph “Sonny” Barger recently died, becoming one of the few famous motorcyclists to earn an obituary in the New York Times. That prompted me to resurrect this post, from an older blog, about an interesting sidebar to the Hells Angels’, and Barger’s, stories.

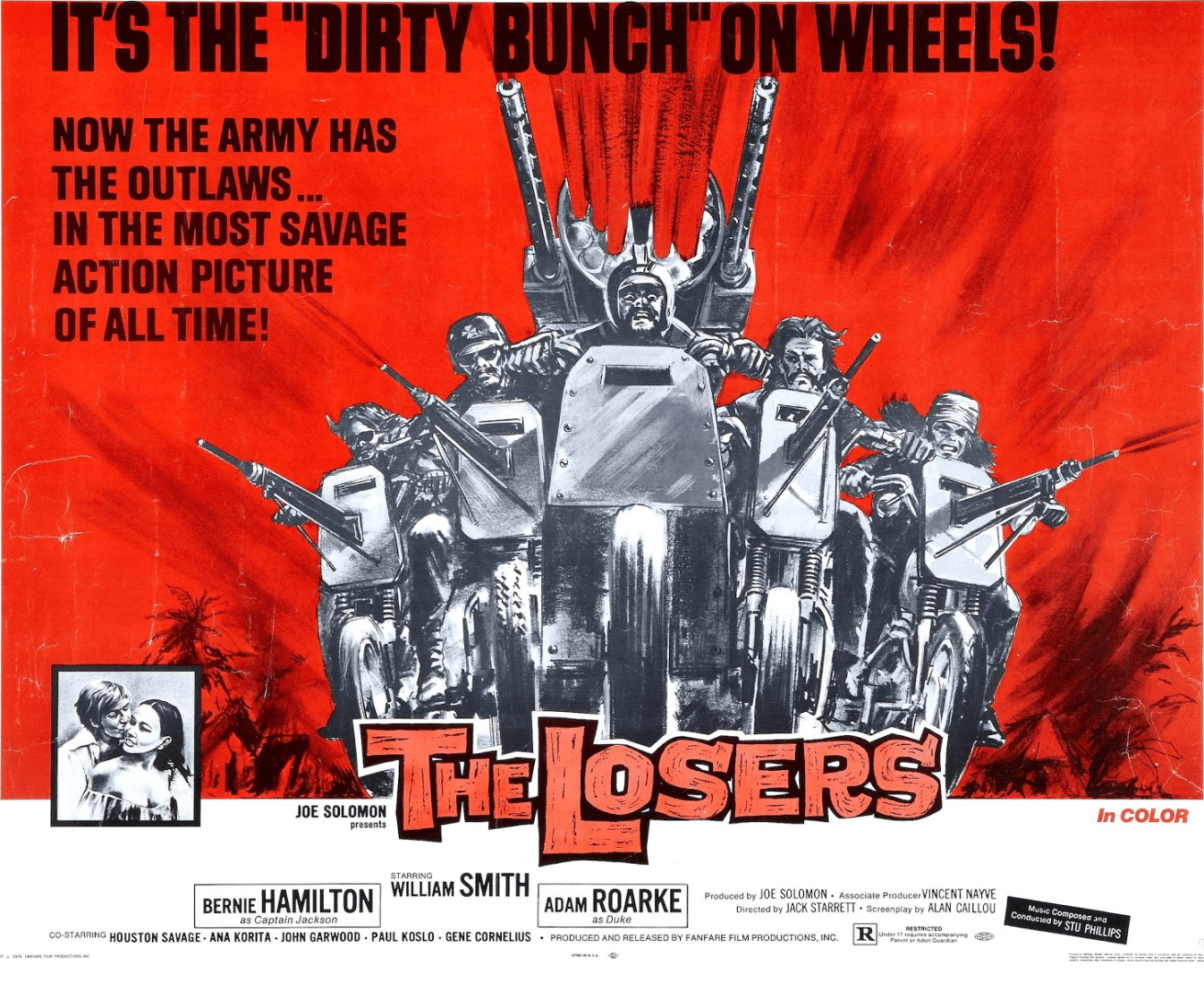

In the course of researching my second triviabook, I stumbled across a bunch of stories that made me think, How has it taken me this long to learn about this? One was the story of NASA’s ‘space minibikes’. Another was related to the Hells Angels and Vietnam. Of course, I already knew that Sonny Barger had volunteered a biker force for duty behind the lines in Vietnam. But I did not realize there actually was a military unit known as Nams Angels. Here’s their story…

A little over fifty years ago, Ralph ‘Sonny’ Barger – the president of the Oakland chapter of the Hells Angels – volunteered his gang for duty in Vietnam.

The press conference, which was held on November 19, 1965, featured Barger and four of his ‘associates’. It was held in the storefront office of Dorothy Connors Bail Bonds. You can follow this link to watch KRON-TV’s report. The journalist who introduces the report can scarcely conceal his own disbelief. The segment opens with footage of an earlier, undated confrontation between Hells Angels and anti-war protesters.

In the fall of 1965, Americans were still not used to big, unruly war protests; those would come later. Until the marchers reached the Hells Angels, things seem to have been generally peaceful. TV footage portrays a fairly cooperative and respectful relationship between thousands of mostly draft-age protesters and an approachable police presence that is positively quaint, compared to what we’d see today.

That ended when Barger started screaming, “Why don’t you people go home, you pacifists!” A cop in standard uniform pushed an Angel back, ordering him to “Back off” and a moment later a 300-pound biker known as ‘Tiny’ was cracked on the skull with a nightstick. Ironically the only police injury occurred when that huge dude slumped to the pavement, breaking a cop’s leg on the way down.

Barger’s often described as a ‘veteran’, which is consistent with the ür-myth of soldiers returning from war and forming motorcycle gangs. The truth is a little more prosaic; Sonny did join the army, but was honorably discharged after a few months when they realized he was actually only 17.

Hunter S. Thompson noted that the march organizers – a loose group of student leftists led by Jerry Rubin – hoped to find kindred spirits in the bikers. But that was not to be; the Angels may have been disenfranchised too, but they were unquestioningly patriotic.

All of which led to the surreal press conference in which Barger announced that the Hells Angels would not attend the VDC march scheduled for November 21, because he was sure that those pacifists would provoke the bikers to violence, which would in turn encourage the public to place its misguided sympathies with the protesters.

“We haven’t been told to do nothin’. This is our own decision. We think it’s best for the country,” said Barger. When asked what the Angels would do instead, Barger added, “We’ll do what we usually do on a Saturday; probably go to the bar and drink a few suds.”

A reporter, perhaps thinking that outlaw bikers – outcasts themselves – would make natural allies with student radicals, asked Barger whether, while he disagreed with the students’ position, he at least defended their right to free speech and assembly. But he literally waved off the question; he never took the bait. (Barger, still in his 20s at the time, comes across as alternately media savvy and, at other moments, hopelessly naïve.)

Barger then read a telegram that he claimed to have sent Lyndon Johnson…

Dear Mr. President,

On behalf of myself and my associates I volunteer a group of loyal Americans for behind-the-lines duty in Vietnam. We feel that a crack group of trained guerrillas* will demoralize the Viet Cong and advance the cause of freedom. We are available for training and duty immediately.

Sincerely,

Ralph Barger

Hells Angels, Oakland CA

If LBJ ever saw the telegram, he certainly didn’t take Barger up on the offer. But ironically, within a few years, there actually was small group of biker-warriors taking the fight to the Viet Cong.

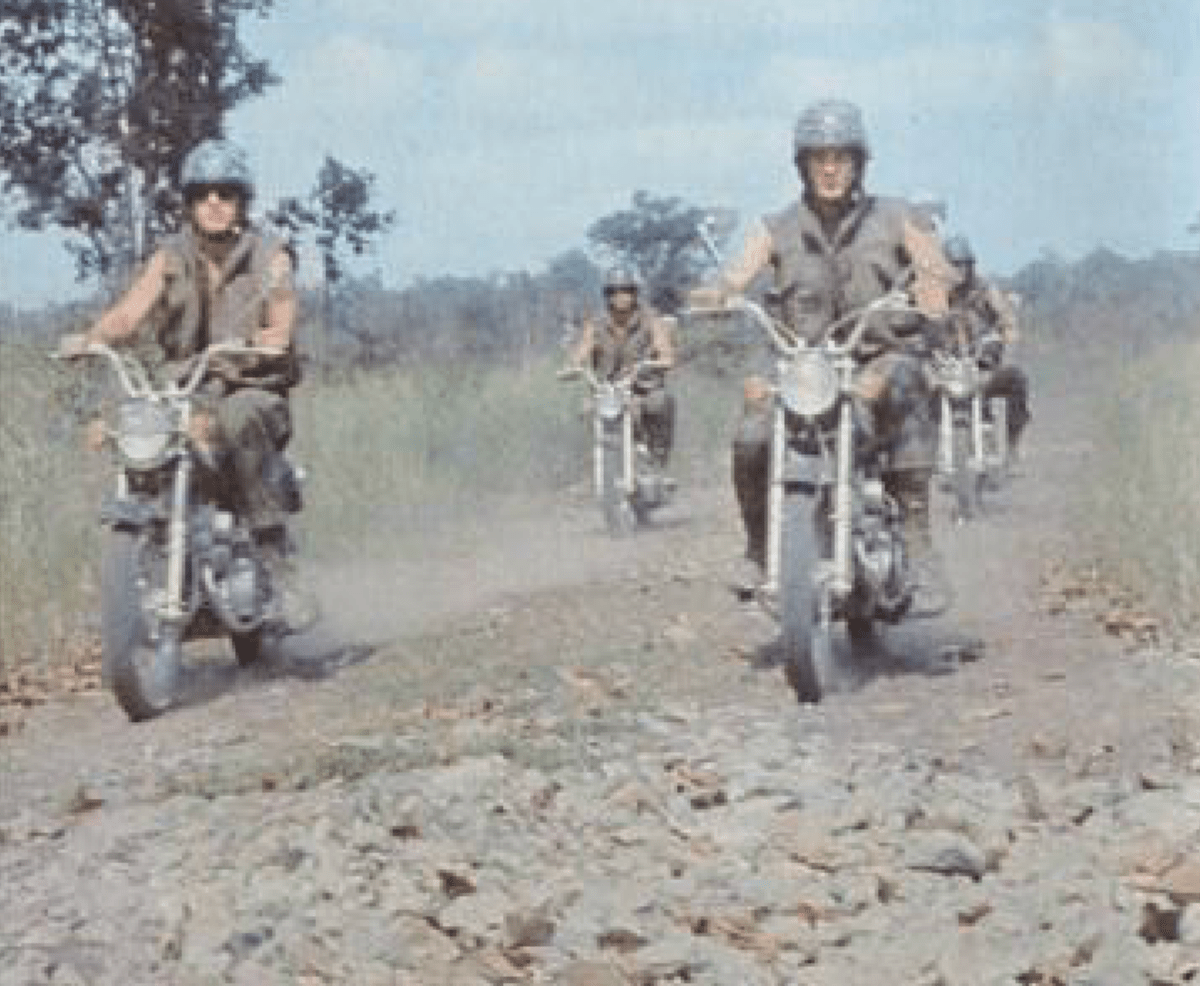

So who were the real Nams Angels? The Recon Patrol of the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, U.S. Army.

In 1969, the 3-22nd’s area of operations was War Zone C, up on the Cambodian border. It was 1,000 square kilometers of marsh and jungle, crisscrossed by a maze of small trails, that served as a hideout and staging area for Viet Cong guerrillas.

The U.S. Army set up camps in there to interdict that activity, and those camps became targets themselves, of VC hit-and-run mortar and rocket attacks.

The commander of 3rd Battalion, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Carmichael, seized upon the idea of using motorcycles as a way for reconnaissance patrols to cover more ground – identifying VC mortar sites, for example.

Carmichael acquired at least four motorcycles, which appear to be pretty much bone-stock Honda CB175 street bikes. Patrols rode out at dawn. I imagine that Sonny Barger would’ve scoffed at those 175cc rice burners – they were hardly intimidating enough for Hells Angels. But the four bikes had a chase vehicle, which was a Jeep with a mounted M-60.

Further up the chain of command, they were skeptical – but not for long. “At first I was very leery of the whole idea, but now I am confident it was a good one,” said Major Joseph Hacia.

I love the idea of four guys – some likely were draftees – who were probably a lot happier to ride those CB175s than they would’a been patrolling on foot. I don’t know how long the 3-22nd’s motorcycle patrols went on, but they were around long enough for those guys to get patched.

Which brings me back to the Hells Angels. I’ve always thought of Barger’s offer – which was almost certainly a publicity stunt, but one that reflected his own genuinely-held views – as one of the first instances of a phenomenon that’s now common: Disenfranchised groups that one might expect to be anti-establishment, but which instead adopt militant patriotism.

I mean, really… The Hells Angels were persecuted by the cops, vilified in the media, and completely ostracized by conservative, mainstream America. And yet they were violently opposed to the student radicals that wanted to stick it to The Man. It seemed that the old saying, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend” no longer held true.

There may be a lesson in reconciliation in all of this.

A few weeks after that press conference, the beat novelist Ken Kesey organized a meeting. A delegation of anti-war protesters came to Barger’s house, where they all dropped acid. Although Barger never really changed his rhetoric, the bikers and the protesters maintained an uneasy truce for the remainder of the Vietnam war.

Leave a comment