Welcome to Warbird Wednesday! Today, we’re visiting a Japanese Navy fighter used during WWII, the A6M Zero. Nicknamed “Zeke”

On Novrmber 14, 2021, I recorded MY VISION for a movie – that has come true! An hour ago I discovered the Confederate plan to have Colorado secede from the Union – so The Traitors could have gold to build more ships that were sinking Union Shipping – as far away as Kamchatka. The captsin of the Shannodoah was told he lost the war, but headed to San Francisco – to burn that ciry down. Was he out for revenge, or, was there a plan to take Calfifornia and make it a Confederate Nation.

Confederate Brig. Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley was leading Trescherous Army of Sneak Attackers from Texas with plans to take over several States, and unleash his Army of Begtrayers on the the Loyal Forces of California. Was my kin, John Fremont aware of these Terrorists disruptimg the peaceful love of Westerners?

STATES RIGHTS – MY ASS!

Remember Pear Harbor!

I want Clint Eastwood to name this movie!

John Presco

Shortly before his death in 1886, James I. Waddell, former captain of the CSS Shenandoah, wrote in his memoirs: “I had matured plans for entering the harbor of San Francisco and laying that city under contribution.”[i]

Waddell never did pass through the Golden Gate, but he came close. He and his ship were notoriously hated in the city by the bay; San Franciscans tried and partially succeeded in exacting revenge.”

“In 1862, Confederate Brig. Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley invaded New Mexico with around3000 Texas cavalry and supporting artillery. Building on earlier Confederate success in organizing a secessionist Arizona Territory, Sibley sought to bring the remainder of the Southwest into the fold, open a path to the Pacific, and secure the recently discovered gold fields of Colorado.”

Gold War

Posted on November 14, 2021 by Royal Rosamond Press

Gold War

An idea for a movie or series by

John Presco

Copyright 2021

Mark Twain offered Thomas Starr King and Herman Melville one of his Cuban cigars to go with their mint julip that Jessie Benton Fremont made for them and the other guests of her salon that she held at her new home in Black Point. Jessie had just introduced Brett Harte, when the conversation digressed to the scuttlebutt over the idea of General Fremont forming a nation in the west now that it was certain the South would secede from the Union. The garrison at Fort Sumpter was put on alert. With the reports coming in that a very large vein of gold was lying thirty feet under the San Joaquin River, and perhaps the whole valley cradled the largest gold deposit in the world, powerful and wealthy men were meeting with John behind closed doors. They wanted him – to grab the gold!

“Scientists are concluding a series of glaciers scraped the gold from the Sierra Foothills as they melted, and lay down a river of gold in the valley. If we don’t grab it, Napoleon may invade from Mexico – with the help of the Hapsburgs.” offered Starr, as he waved off Twain’s cigar. “I don’t smoke!”

“What is that?” Melville asked, as he saw puffs of smoke come through the haze that lingered at the Golden Gate. Then came the booms of canon.

“What the hell!” exclaimed Twain, and ran inside to get a spyglass. He emerged with General Fremont. Together they focussed on the warships that came sailing out of the mist, all cannons firing on the small fortification at the point.

“They’re flying the new flag of the Confederacy!” cried the General.

“Look! There fly the flag of Napoleon!” shouted Melville!

“To arms!” cried Mr. Harte, and he was given a look that went around world. At the exact same time a Prussian fleet sailed out of port in Chile. There were three frigates, and five troop transports. But what got the attention of the German colonizers, and the Native Americans, was the sight to the four ironclads that belched smoke and steam.

“Laviathans!”

Prussia had made an offer to purchase California, but the discovery of gold, and the Gold Rush, forced the military kingdom that threatened Europe, to back out the deal. But, the Prussian Royalty had a plan. Timing is everything. When Wilhelm got news of – The Firing On Fort Mason – his fleet was sighted by the citizens of Los Angeles. Many of them were German immigrants. On cue, they formed militias, and would march into the San Joaquin Valley from the South!

‘When Senator Thomas Hart Benton was informed the South had landed an army in Oakland, he told his men to send the Ozark Brigade to Oregon to meet the British force he knew would come down from Canada to fight their old foe, the Scott-Irish. There were Germans from Saint Louis in this bunch.

“Gentleman! The Gold War….has begun!”

Confederates Invade San Francisco?

Posted on February 9, 2018

Shortly before his death in 1886, James I. Waddell, former captain of the CSS Shenandoah, wrote in his memoirs: “I had matured plans for entering the harbor of San Francisco and laying that city under contribution.”[i]

Waddell never did pass through the Golden Gate, but he came close. He and his ship were notoriously hated in the city by the bay; San Franciscans tried and partially succeeded in exacting revenge.

Shenandoah was one of the most successful of Confederate commerce raiders, the only one to circumnavigate the globe. While the war struggled to conclusion and the nation began to bind its wounds, these Rebels invaded the north—the deep cold of the Bering Sea between Alaska and Siberia—and captured 26 Yankee whalers. It was June 1865.

They fired the last gun of the Civil War, ten weeks after Appomattox, set the land of the midnight sun aglow with flaming enemy vessels, and almost became trapped by ice. This was an unprecedented accomplishment that a few months before would have been greeted with jubilation in the South and despair in the North. Waddell crammed all the hundreds of men from the destroyed ships onto four of the oldest and slowest whalers and sent them off to San Francisco.

Confederates also captured newspapers from San Francisco via Hawaii dating as late as the previous April 17, informing them of Lee’s surrender and Lincoln’s assassination. The Southern government had fled Richmond said some papers, but others stated that Lee had joined General Johnston in North Carolina for an indecisive battle against General Sherman.

The news also carried an impassioned proclamation by President Davis—issued on the run from Danville, Virginia—announcing that the war would be carried on with renewed vigor and exhorting his people to bear up heroically. Months later and half a world away, Shenandoah Rebels took this to heart. They were very worried, but not about to believe all the Yankee propaganda, that their cause was lost, and their sacrifices for naught.

First Lieutenant William Whittle had anticipated the loss of Charleston and Savannah, and even the evacuation of Richmond once Wilmington was gone, but not Lee’s reported surrender. “All this last I put down as false…. I do not believe one single word.” Ship’s Surgeon, Dr. Charles Lining: “I was knocked flat aback. Can I believe it? And after the official letters which are published as being written by Grant & Lee, can I help believing it?”[ii]

By mid-July, Shenandoah was finally headed south, bowling along eight hundred miles out in the Pacific near the latitude of San Francisco. The captured newspapers had reported only one warship present in the bay: the USS Comanche, a Passaic-class monitor armed with two powerful XV-inch Dahlgren smoothbores.

Comanche had been constructed in New Jersey, disassembled, shipped around the Horn in a sailing ship, and reassembled. She was the only ironclad on the coast. The remainder of the sparse Pacific Squadron was spread up and down the rim of Central and South America, primarily protecting the approaches to Panama. In his memoirs, Waddell described his plans.

Comanche was commanded by Lieutenant Commander Charles J. McDougal, an “old, familiar shipmate” of Waddell from before the war. McDougal was “fond of his ease.” He was no match for any Shenandoah officer “in activity and will.”

It would be easy enough, continued Waddell, to enter the harbor at night, ram a surprised Comanche, overwhelm her decks and hatches with armed borders, and take control without loss of life. “E’er daylight came, both batteries could have been sprung on the city and my demands enforced.”[iii]

The practicality of such a scheme can be seriously doubted; San Franciscans were not known for shyness in the face of a good fight. But whatever Shenandoah’s captain was thinking at the time about invading the city, he apparently did not share these ideas with his officers. Other than the final writings of an ageing warrior, this plot is nowhere mentioned in contemporary sources, including several detailed officer cruise journals, letters, memoirs, and Waddell’s own extensive, immediately post-war report.

Waddell did claim in his post-war report an intention to run along the coast with the north wind sweeping down Lower California, keeping a sharp lookout for enemy cruisers and for gold packets on the Panama to San Francisco run. Some of his officers were itching to take a fat clipper on its way to or from the Orient.

However, as Midshipman Mason confided to his journal, Shenandoah’s actual course took them too far off the coast to meet mail steamers and nowhere near the San Francisco to Hawaii and China trade routes. Waddell seemed determined to get around the tip of South America as quickly as possible without seeking more captures, which would be just a matter of luck along this track. “The skipper of course must know best, but I think we might make the attempt.”[iv]

The denizens of San Francisco, meanwhile, were very aware and acutely worried about the Rebel raider, but they had no idea where in the wide ocean she was. They had heard nothing since Shenandoah’s visit to Melbourne six months previously.

Then on July 20, the old whaler Milo staggered through the Golden Gate with two hundred refugees from the Bering Sea. “Wholesale Destruction of American Whalers,” trumpeted the San Francisco Bulletin. “Probable Destruction of Another Fleet of Sixty Whalers.” “The most extensive and wholesale destruction of American shipping yet committed by any rebel pirate since the beginning of the war.”

“Great apprehensions felt by mercantile community of San Francisco,” reported the commandant of the Mare Island Navy Yard to Navy Secretary Welles. Merchant ship owners and underwriters requested authority to charter, arm, and man the fast Pacific Mail Company steamer Colorado–the only available vessel capable of catching the swift Rebel–to pursue Shenandoah. (They would receive the authority a month too late.)[v]

On July 22, the Sacramento Daily Union reported a conversation in a bar with sailors of the American bark Mustang, which had recently returned from Melbourne. On a quiet night the previous February, Shenandoah had been lying placidly at anchor in the dark Australian harbor.

These sailors had, so they said, rowed a boat silently over to the Rebel vessel until the huge black hull, towering masts, and tracery of rigging loomed above, blotting out shore lights. At the end of a line behind the boat floated a cask containing 250 pounds of black powder with a cocked revolver and cord attached.

Only occasional soft voices and steps of the watch on deck disturbed the sleeping vessel. The intruders secured the cask to the hull with a chain and rowed away, intending to pull the cord and detonate the deadly device from a distance. But the chain broke, aborting the operation.

Had this attempt to blow up the warship with a “torpedo” succeeded, the irony would have been manifest as one of the Confederacy’s most innovative weapons was turned against it. Given Shenandoah’s high state of alert at the time against just such dangers, one can question that the affair occurred exactly as related. But the sentiment was genuine and this or something like it must have been contemplated by more than one group of enraged Yankees.[vi]

On August 2, Shenandoah encountered the English bark Barracouta, thirteen days from San Francisco bound for Liverpool with newspapers only two weeks old confirming that their country had been overrun, president captured, armies and navy surrendered, the people subjugated. “The darkest day of my life,” wrote Lieutenant Whittle in his journal. “The past is gone for naught—the future is dark as the blackest night. Oh! God protect and comfort us I pray.”[vii]

Waddell struck the guns below, assumed the guise of an unarmed merchantman, and began a long run around the Horn. November 6, 1865: Shenandoah limped into Liverpool. Captain Waddell lowered the last Confederate banner without defeat or surrender and abandoned his tired vessel to the British.

Hatred for James Waddell in San Francisco lingered long after the war. By 1875, he had resumed full American citizenship and was engaged by the same Pacific Mail Company to command its newest liner, the 4,000-ton steamer City of San Francisco on its maiden voyage from that city to Sydney via Honolulu.

San Francisco papers carried angry editorials decrying the potential presence of a Confederate marauder in the city. Mobs of whalemen threatened violence over losses suffered a decade earlier. Amidst the uproar, City of San Francisco sailed with a substitute captain. Waddell assumed command on a later voyage.

__________________________________

Author’s Notes

Jessie Fremont ins Sunshine Magazine said the British had plans to take over the San Joaquin Valley and move tens of thousands of Irish Catholics there. Prussian offered six million dollars for California. Radical German Forty-Eighters put Lincoln in office. Lincoln put tens of thousands of Abolitionist German Immigrants in Freemont’s ‘Mountain Department’ with no Confederate army anywhere near. Did Lincoln fear the Turner Germans would throw Lincoln out of office in a coup, because he kept putting off Emancipating the slaves? Did Joseph Lane have plans to make Oregon a slave slate – and California? Did Blair have a plan to make peace with the Southern slave owners by offering them the West, and ending slavery in the Original Thirteen Colonies? The British may have promised to thwart this idea because they were putting an end to slavery all over the world.

An hour ago I read an article by Joe Ryan who asks the questions I have been asking for ten years – at least! I have wondered if my great grandfather, Carl Janke, was part of a Prussian plan to colonize California – without a purchase. Just start moving in Germans from all over the world. Much of the world’s cotton is grown in the San Joachim Valley. How close did we come to having poor Irish Catholics being the Cotton Picker of The World…Cotton Mundi. Protestant England is free of the Pope – alas! Remember Drake and the sinking of the Spanish Armada that was built with New World gold.

Mankind’s love of gold……will be with us forever!

John Presco

President: Royal Rosamond Press

Understanding General John Fremont (joeryancivilwar.com)

In the process, harking back to Frémont’s glory days as the Pathfinder, Lincoln created the “Mountain Department” and sent Frémont on an illusionary mission to nowhere, conveniently stashing on the perimeter of Virginia territory thirty thousand men. It appears that most of these men were Germans, many of whom spoke no English. Whether this fact has something to do with Lincoln’s thinking here, who knows?

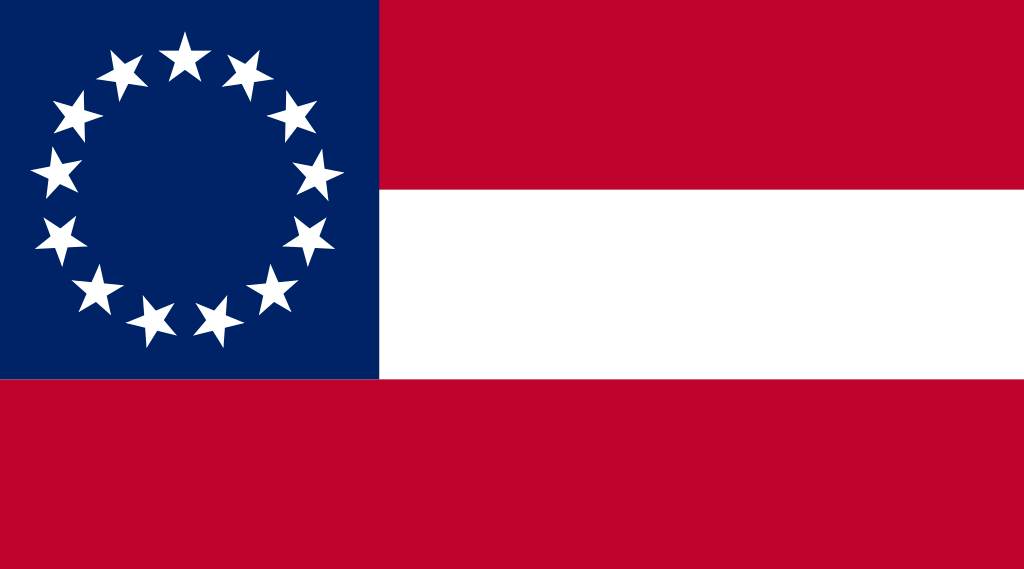

Flags of the Confederate States of America – Wikipedia

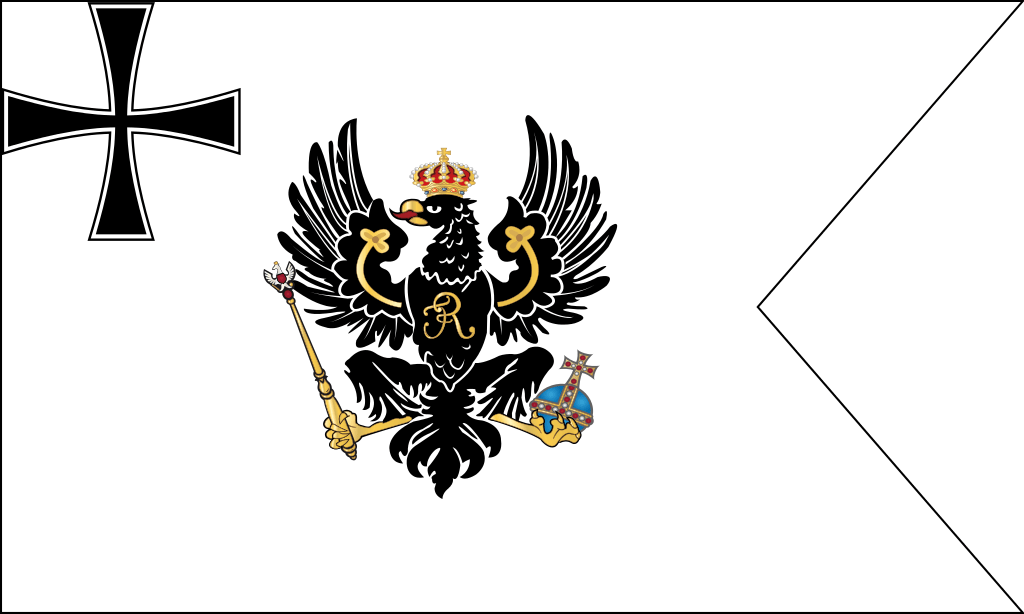

The Prussian Navy was created in 1701 from the former Brandenburg Navy upon the dissolution of Brandenburg-Prussia, the personal union of Brandenburg and Prussia under the House of Hohenzollern, after the elevation of Frederick I from Duke of Prussia to King in Prussia. The Prussian Navy fought in several wars but was active mainly as a merchant navy throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as Prussia’s military consistently concentrated on the Prussian Army. The Prussian Navy was dissolved in 1867 when Prussia joined the North German Confederation, and its naval forces were absorbed into the North German Federal Navy.

The naval preference of the last Prussian king, German Emperor Wilhelm II, prepared the end of the Prussian monarchy. The German naval buildup of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was one of the causes of World War I; and it was the mutinying sailors of the High Seas Fleet who forced the abdication of the Emperor during the German Revolution of 1918–1919. The Navy continued as the Reichsmarine (Reich Navy) and later the Kriegsmarine (War Navy), until at the end of World War II, it faced its own end.

Between the mid-1860s and the early 1880s, the Prussian and later Imperial German Navies purchased or built sixteen ironclad warships.[1][a] In 1860, however, the Prussian Navy consisted solely of wooden, unarmored warships. The following year, Prince Adalbert and Albrecht von Roon wrote an expanded fleet plan that included four large ironclads and four smaller ironclads. Two of the latter were to be ordered from Britain immediately,[8]

Confederate States Navy – Wikipedia

List of ironclad warships of Germany – Wikipedia

Civil War at Fort Mason

Understanding John Fremont

By: Joe Ryan

Share this:

We Will Soar At Black Point

Posted on February 19, 2017 by Royal Rosamond Press

Those with Free Spirits, who know how to be released, and soar, come to Black Point and Fort Mason. Here we will make a stand for Arts and Culture. Here the Nation of California will be born. The epicenter is here. We will put on a lightshow. They will see our light in the sky, and in the bay, playing with whales and dolphins. They will marvel.

Jessie Benton Fremont held a salon at Black Point. Mark Twain was a frequent guest. Rena gave me permission to install her in ‘The Muse Hall of Fame’. If not for the painting I did of Rena, Christine would never have married Garth Benton. I am the official Benton Historian. There is not other.

I just read Carrie Fisher predicted her own death, as did Mark Twain, and, allegedly my sister. Carrie was hired to do a screenplay about Christine. Debbie died the next day.

Join us!

Jon ‘Master of the Rose’

Blunt said, Fisher also had a scary premonition.

“She put a cardboard cutout of herself as Leia outside my room, with her date of birth and date of death on her forehead,” he told the Times. “I’m trying to remember what the date was, because it was around now — and I remember thinking it was too soon.”

JOELY: I’ve been having an out-of-body experience. The world lost Carrie and Debbie, of course, but– and– and Princess Leia and we lost our hero. We lost– our mirror.”

http://abc7chicago.com/entertainment/carrie-fishers-sisters-open-up-about-her-final-moments/1683949/

http://www.militarymuseum.org/BlackPointBty.html

”

Our members are to hear much about this Cathedral of the Soul in the near future, and at present I wish merely to announce its name and present to you a brief picture of what it is. This cathedral is that great holy of holies and Cosmic sanctum maintained by the beams of thought waves of thousands of our most advanced members, who have been prepared and trained to direct these beams of thought at certain periods of the day and the week toward one central point, and there becomes a manifest power, a creative force, a health giving and peace giving nucleus far removed from the material trials and problems, limitations and destructive elements of the earth plane.

While men have been busy planning, building, and directing great spires and towers of earthly cathedrals that would reach high into the heavens and become the material abiding place for those in devotion and meditation, we have been creating this cathedral of prayer and illumination, Cosmic joy, and peace high above every material plane and ascent into the Cosmic itself.”

Mark Twain

Twain’s landing place was San Francisco. As Ben Tarnoff explains in his deftly written, wholly absorbing “The Bohemians: Mark Twain and the San Francisco Writers Who Reinvented American Literature,” the city was an ideal crucible for an ambitious young writer on the make. It prospered during the Civil War and had a literate population that craved a new kind of writing. Important patrons such as Jessie Benton Fremont and Thomas Starr King nurtured the nascent talents of Charles Warren Stoddard, Ina Coolbrith, and most prominently Harte, a disciplined dandy and a brilliant mentor and editor who founded The Californian, a literary paper where Stoddard published his first poem and Twain refined his style in the fall of 1864.

http://galleryoftherepublic.com/index.php?id_product=29&controller=product

http://www.militarymuseum.org/BlackPointBty.html

Jesse Benton Fremont

by Susan Saperstein

She is thought to be the real author behind the successful writings of John C. Fremont (general, senator, presidential candidate, and the Pathfinder of the West) describing his explorations. Jesse Benton Fremont (1824– 1902), Fremont’s wife, was also the daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, a leading advocate of Manifest Destiny, a political movement pushing expansion to the West. And in her event-filled life, some of her happiest times were at her house in San Francisco’s Black Point area, now known as Fort Mason.

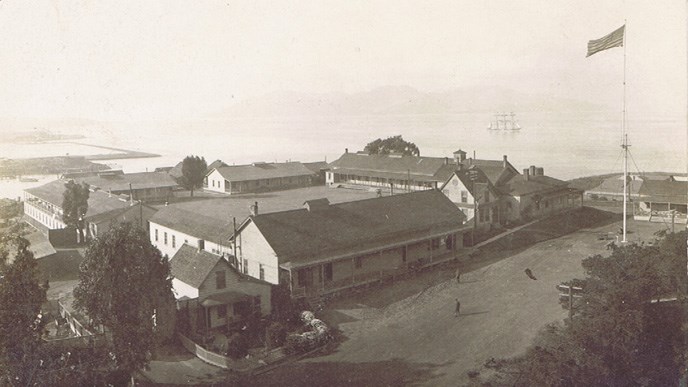

The Fremonts lived there between 1860 and 1861. The prop- erty included three sides of the point, and Jesse described it “like being on the bow of a ship.” They had a clear view of the Golden Gate, so named by John when he first viewed it in 1846. Alcatraz was so close that Jesse is said to have called the lighthouse on the island her nightlight.

The Spanish called the area Point San Jose and built a battery in 1797. However, cold winds and fog soon made the cannons useless. By the time the Mexicans were ruling in the 1820s, the area was known as Black Point for the dark vegetation on the land.

Their house was one of six on the point. Jesse remodeled the house and added roses, fuchsias, and walkways on the 13 acres. Their home became a salon for San Francisco intellectuals. Thomas Starr King, the newly appointed minister of the Unitarian church, was a fixture for dinner and tea. Young Bret Harte, whose writing Jesse admired, became a Sunday dinner regular, as did photographer Carleton Watkins. She invited literary celebrities when they came to townó including Herman Melville, who was trying to get over the failure of Moby Dick. Conversations in her salon led to early conservation efforts when Jesse and a group including Watkins, Starr King, Fredrick Law Olmsted, and Israel Ward Raymond lobbied Congress and President Lincoln to preserve Yosemite and Mariposa Big Trees. Jesse’s husband, however, often away on business ventures, was not a regular at her gatherings.

Jessie Benton Fremont at Blackpoint

Historical Essay

by Jo Medrano

Mrs. General Fremont on porch at Black Point, 1863.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Mrs. General Fremont on her porch at Black Point, c. 1863.

Photo: Jesse Brown Cook collection, online archive of California

Black Point (now Fort Mason), 1870. Spring Valley Water Co. brought water through the flume that skirts the cliffs. Small farms run down to the shore. Alcatraz is in the distance.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

John C. Fremont bought a farm for his wife Jessie on the north edge of San Francisco, on a small rocky peninsula then known as Blackpoint, about 1860. At the time of purchase, they were living in Bear Valley in the Sierras. In Bear Valley Jessie Fremont developed physical problems due to the intense heat. She wrote that a buried egg would cook in just a few minutes. One account states that it was 106 degrees at sunset–not an uncommon temperature that year. So we can probably imagine her delight when John C. came back from a business trip to San Francisco in 1861, and told her they were moving to the city. Blackpoint was a self-sustaining farm, and Jessie’s favorite home. She had relatives living with her, as well as visits from other relatives in addition to local and national celebrities.

Spring Valley Water Company flume is visible at right; Small farms on the hill above c. 1870

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

As a matter of fact, a influential San Franciscan, I.W. Raymond, visited the Fremonts in Bear Valley and traveled with them to see the place that wasn’t yet named Yosemite. He was a key person in the 1864 action of President Lincoln which made Yosemite a protected place.

Black Point is described in “Jesse Fremont: A woman who made history” as “a small headland jutting out into the channel entrance of the harbor, in fact directly opposite the Golden Gate, affording an unbroken view westward to the Pacific and eastward toward the mountains of Contra Costa.” Jessie said she “loved this sea home so much that I had joy even in the tolling of the fogbell”. It was here she planned and built her “sunset beach.”

The federal government took over Black Point soon after Jessie and John Fremont went back east to be involved in the civil war. John fought for compensation for the expropriated house and land until the day he died.

When Thomas Starr King first walked to the pulpit of the San Francisco Unitarian Church in 1860, the eyes of the congregation turned to this small, frail man. Many asked, “Could this youthful person with his beardless, boyish face be the celebrated preacher from Boston?”

King laughed. “Though I weigh only 120 pounds,” he said, “when I’m mad, I weigh a ton.”

That fiery passion would be King’s stock in trade during his years in California, from 1860 to 1864. Abraham Lincoln said he believed the Rev. Thomas Starr King was the person most responsible for keeping California in the Union during the early days of the Civil War.

King’s reputation as a noted orator had led the San Francisco congregation to ask him to come west, with little hope he would agree. During his 11 years as minister of Boston’s Hollis Street Unitarian Church, King increased the congregation to five times its original size and pulled the church out of bankruptcy. Ralph Waldo Emerson, noted essayist and poet, said after hearing one of King’s sermons, “That is preaching!” Churches in Chicago and Brooklyn sought King as their minister, but this popular Boston pastor rejected them. San Francisco, he decided, offered the greatest challenge.

California in Crisis

California was headed into a crisis. At hand was a showdown between the free states of the Union and the slave states. California’s governor and most members of the state legislature were sympathetic to the Confederacy. The only effective voice against slavery, Sen. David C. Broderick, had been killed in a duel the year before.

The San Francisco congregation’s initial disappointment about King’s slender, boyish appearance soon gave way to wonder, then delight at his rich, golden voice. Not only did King establish his reputation as an orator and preacher that first Sunday in San Francisco, but the news soon spread statewide, attracting worshipers from Stockton and Sacramento.

Less than a month after King arrived in California, the Republican National Convention met in Chicago and nominated Abraham Lincoln as its presidential candidate. In the following election, Lincoln carried California by only 711 votes.

Southern states soon abandoned the Union. The crucial question on the minds of many Americans was: Would California join them and deliver the state’s immense natural resources into the hands of Confederate President Jefferson Davis? Support for secession was strong in southern California, where the Confederate flag had flown over Los Angeles’s main plaza on the Fourth of July.

At that time the U.S. Congress was so convinced of a secessionist plot that it required Easterners to secure passports for travel to California. Justifying Congress’ fears was a secret paramilitary California secessionist organization of about 16,000 members, called the Knights of the Golden Circle.

On George Washington’s birthday in 1861, King fired an opening salvo in support of his country. He spoke for two hours to over a thousand people about how they should remember Washington by preserving the Union.

Pledging California

“I pitched into Secession, Concession and (John C.) Calhoun (former U.S. vice president), right and left, and made the Southerners applaud,” King recalled. “I pledged California to a Northern Republic and to a flag that should have no treacherous threads of cotton in its warp, and the audience came down in thunder. At the close it was announced that I would repeat it the next night, and they gave me three rounds of cheers.”

Speaking up and down the state, King visited rugged mining camps and said he never knew the exhilaration of public oratory until he faced a front row of men armed with Bowie knives and revolvers. His friend, Edward Everett Hale, who made a similar contribution to saving the Union through his moving story, “The Man Without a Country,” said, “Starr King was an orator no one could silence and no one could answer.”

King covered his pulpit with an American flag and ended all his sermons with “God bless the president of the United States and all who serve with him the cause of a common country.” At one mass rally in San Francisco, 40,000 turned out to hear him speak. A group of Americans living in Victoria, B.C., sent him $1,000 for his work to preserve the Union. King was beginning to turn the tide.

In 1861, he threw himself into the gubernatorial campaign of his parishioner, Leland Stanford. King and author Bret Harte often accompanied Stanford on speaking tours. Stanford won an overwhelming victory and King sighed with relief.

“What a privilege it is to be an American!” he said. “What a year to live in! Worth all other times ever known in our history or any other!”

A New Front

The battle to keep California in the Union won, King now turned to the needs of its soldiers. The Union Army lacked provisions and medical personnel. Much of its food was rotting because of spoiled goods sold to the Army by war profiteers. Soldiers lacked sheets and blankets, and disease took a greater toll than Confederate bullets.

In response, the Rev. H.W. Bellows of New York organized the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a forerunner of the American Red Cross. Starr King immediately pitched in to help. Out of $4.8 million the commission raised throughout the U.S., King raised $1.25 million in California. About $200,000 came from San Francisco, a figure all the more impressive because of a series of natural disasters in the state, including a massive flood that turned the Sacramento-San Joaquín Valley into a vast lake and a drought that wiped out the wheat crop.

Now King found himself raising funds for flood and drought relief. He also carved out time to work for the rights of San Francisco’s African Americans and Chinese.

“We know,” said Edward Everett Hale of King, “that here is a heart as large as the world, so that you can not make it understand that it should hold back from any service to be rendered to any human being.”

Because of King’s success in patriotic and charitable causes, powerful friends encouraged him to run for the U.S. Senate. But he refused, saying he feared it would lead to political compromise and impair his ability to speak forthrightly. “I would rather,” he said, “swim to Australia.”

Relaxation and joy came from exploring California’s wilderness. He was among the first 100 Euro-Americans to visit Lake Tahoe. To him, the blue lake and green pines seemed in harmony with the deepest religion of the Bible.

Yosemite Valley and its giant trees gave him special delight. Back in New England he enjoyed exploring the White Hills of New Hampshire and wrote a book about them, “The White Hills—Their Legend, Landscape and Poetry.”

On entering California’s great valley, he said, “The Ninth Symphony (by Beethoven) is the Yosemite of music! Great is granite and the Yosemite is its prophet!” He climbed above the falls, attracted by a dome of granite towering 13,600 feet over the valley. Today it bears his name, Mt. Starr King.

San Francisco Church

Despite his many commitments in California, King always put his church first. When he arrived in San Francisco in 1860, the congregation struggled with a $30,000 debt. Within the first year, King managed to raise the funds to pay it off. Now he turned his attention to an expanding congregation in a too-small church. In October 1862, he set an $80,000 fundraising goal. By December of that year, the cornerstone of a new church was laid. In January 1864, King and his congregation celebrated the completion of the new building at 133 Geary street, adjacent to present-day Union Square. (The congregation eventually relocated its church again in 1889 to the corner of Franklin and Starr King streets in San Francisco, where the First Unitarian Universalist Society church stands today.)

His congregation now prosperous, the Union Army driving to victory and the Sanitary Commission on solid footing, King decided to take a much-needed sabbatical. He planned to rest, travel and write a book about the Sierras.

Colorado’s Confederate Hideout

Posted on October 11, 2022

In 1862, Confederate Brig. Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley invaded New Mexico with around3000 Texas cavalry and supporting artillery. Building on earlier Confederate success in organizing a secessionist Arizona Territory, Sibley sought to bring the remainder of the Southwest into the fold, open a path to the Pacific, and secure the recently discovered gold fields of Colorado.

Sibley was relying in part on support from Confederate sympathizers in the territory that he would be occupying. His artillery chief, Major T.T. Teel, wrote, “His campaign was to be self sustaining … Sibley was to utilize the results of Baylor’s successes, make Mesilla the base of operations, and with the enlistment of men from New Mexico, California, Arizona and Colorado form an army.”1

Sibley never reached Colorado; his army was turned back at the battle of Glorieta Pass in northern New Mexico. They were stopped, in large part, by Colorado volunteers who marched hundreds of miles to make it to the battle. But how much support could Sibley really have hoped to gain in Colorado?

At the outbreak of the war, the territory was only recently established. Most White settlement as of the Civil War had been prompted by the discovery of gold in the late 1850s, and the associated businesses that sprang up to support waves of prospectors. With a sparse population, slow communications and rumors running wild, Union commanders and the federal government were forced to speculate just how high the initial secessionist wave would crest.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that there was at least an undercurrent of support for the Confederacy. A Confederate flag was hoisted on Larimer Street in Denver, along with reports of sporadic confrontations in the city.2 Colonel R.S. Canby, commanding Union forces in New Mexico, wrote to his superiors St. Louis warning that, “The trains en route for this country are again threatened by marauding parties from Colorado Territory.” He voiced similar concerns to authorities in Washington, specifically worrying that Confederate sympathizers would attempt the “seizure of military posts or public property.”3

The territorial government of Colorado was also convinced that there was a significant risk. On October 25, 1861, Governor William Gilpin wrote that “The malignant secession element of this Territory has numbered 7,500. It has been ably and secretly organized from November last, and requires extreme and extraordinary measures to meet and control its onslaught.”4

7,500 Confederate supporters would have accounted for about a fifth of the territory’s population of 34,277, as of the 1860 census. Census takers also collected, and reported on, respondents’ native states. According to that data, only 8% of Coloradans originally hailed from a state that seceded, while another 16% called a border state home, mostly Missouri and Kentucky.5

The largest reported concentration of Confederate support was in a small valley in southern Colorado called Mace’s Hole. Named for Juan Mace, an outlaw in the area in the 1850s and 1860s, the location had easy access to major thoroughfares, while also being tucked away and easily defended, made it a good hideout for both bandits and clandestine Confederates in Union territory.

Daniel Conner, a Kentuckian who ventured west to Colorado in search of gold and later sought to join up with Confederate forces, noted the great care that was taken to keep their recruitment operation off the radar of Union authorities:

“No new recruit was ever allowed to come directly to Mace’s Hole. They were recruited and sent to a small camp up above Pike’s Peak more than fifty miles from Mace’s Hole. This small camp was in charge of trusty men, some of whom would accompany the recruit to Mace’s Hole as their escort. By this means a traitor could not jeopardize the safety of any but the little recruiting squad.”6

Conner cites 600 Confederate troops in Mace’s Hole, a significant force when we consider the small numbers of troops involved in campaigns this far west. Sibley had 3000 troops at the beginning of his campaign At the battle of Glorieta, it’s likely that neither side fielded much over 1,000 men. Armed, trained, and well-led, 600 Confederates would have been difficult to pry out of this position, which Conner described in detail after the war:

“But from my best recollection, this hole was about half a mile or more in diameter and completely hedged in by a perpendicular wall, varying in height from ten feet near the ditchlike entrance around the circle, rising gradually higher as it neared the higher ascending mountain, where it was hundreds of feet in height, then gradually descended around the other half-circle to the mouth of the ditch or entry. This entry was a narrow lane between two walls also, until it opened on the plains. The ditch was like the ‘hole’ – bounded by perpendicular walls and possibly from twenty to fifty feet in width. Such was the place selected by Col. John Hefffiner in which to organize his Confederate regiment.”7

Having been there, I can confirm it’s a reasonably accurate description. It was an ideal location for mobilizing troops in unfriendly territory,easily kept out of sight, with ready access to water and provisions, and easily defensible at the entrance. What kind of impact might 600 organized, armed Confederate troops have had operating out of this area?

Conner notes that Mace’s Hole “was within a mile of the military road leading from Denver, Colorado to Fort Union, New Mexico.” Any organized force there would have been in a strong position to disrupt Federal communications, panic Union authorities in the territory, and potentially support Sibley.8

More intriguingly, Conner describes a detailed plot that was hatched to capture the lightly defended Fort Garland, near the border of New Mexico and Colorado. He paints a picture of a garrison of only 30 or 40 men, sympathetic to the Confederate cause, and sitting on hundreds of small arms that could be used to fully equip the regiment forming at Mace’s Hole.9

Conner was writing after the war, but at least in hindsight, the plan was reasonably well-crafted. It’s a little more optimistic than a report in the official records from around that time, which showed 137 men present for duty at the fort. But with 600 men, supporters inside the walls, and the element of surprise, it’s at least conceivable that the plan could have succeeded.10

There are plenty of red flags here to give us pause, though. I’ve often seen Conner’s account cited at face value, implying there were 600 Confederate troops actively under arms. It’s an intriguing possibility, but we should at least be skeptical of the idea that there was really a militarily significant force available here. They were clearly relying on arms captured from Fort Garland to army the regiment, and Conner’s description of the 600 men in the unit includes the important hedge that “really there was never this number in the hole at once, but this was the headquarters.” There’s a world of difference between 600 reported recruits who are never seen together in the same place, and an effective fighting force taking the field together at the same time.11

This is a familiar theme for anyone who’s studied other Confederate offensives in 1862. Those campaigns were also launched, in part, with the idea that supporters in Maryland and Kentucky would lead to an outpouring of recruits and supplies, but that proved to be wishful thinking.

Ultimately, the nascent Confederate force at Mace’s Hole was broken up by Union forces before it could have any impact on the war. Sibley abandoned New Mexico after this defeat at Glorieta, and for the remainder of the war, Colorado faced few Confederate threats. The occasional rumor surfaced of a Confederate raid from Texas, without ever coming to fruition. A handful of partisan raids by Confederate sympathizers would make the papers, but they straddled the gray area between irregular warfare and general crime.

Mace’s Hole was renamed Beulah in 1876, when Colorado became a state. Beulah is still there today, a little off the beaten path, but worth visiting if you find yourself in the area.

- Major T.T. Teel. “Sibley’s New Mexico Campaign – Its Objects and the Causes of its Failure,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 1888, 700.

- Smith, Duane A. The Birth of Colorado: A Civil War Perspective. University of Oklahoma Press. 1989. 12.

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), Series 1, vol. 4, pages 68, 74.

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), Series 1, vol. 4, page 73.

- Statistics of the United States Census (Including Mortality, Property, &c.) in 1860, Washington Government Printing Office, 1866, 549. To be precise, 8.47% of the population hailed from seceded states, 16.44% from border states, and 66.11% from solidly Union states. The remaining 8.99% were foreign-born, didn’t answer, or claimed other territories as home…and a single soul had no native state because they were born at sea. It’s worth noting that in 1861, the U.S. Marshal conducted a separate census that arrived at a significantly smaller population for the territory, but there’s some reason to be skeptical of that data.

- Conner, Daniel Ellis. A Confederate in the Colorado Gold Fields. University of Oklahoma Press. 1956. 138.

- Conner, 134.

- Conner, 134.

- Conner, 146-147.

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), Series 1, vol. 4, page 696.

- Conner, 133

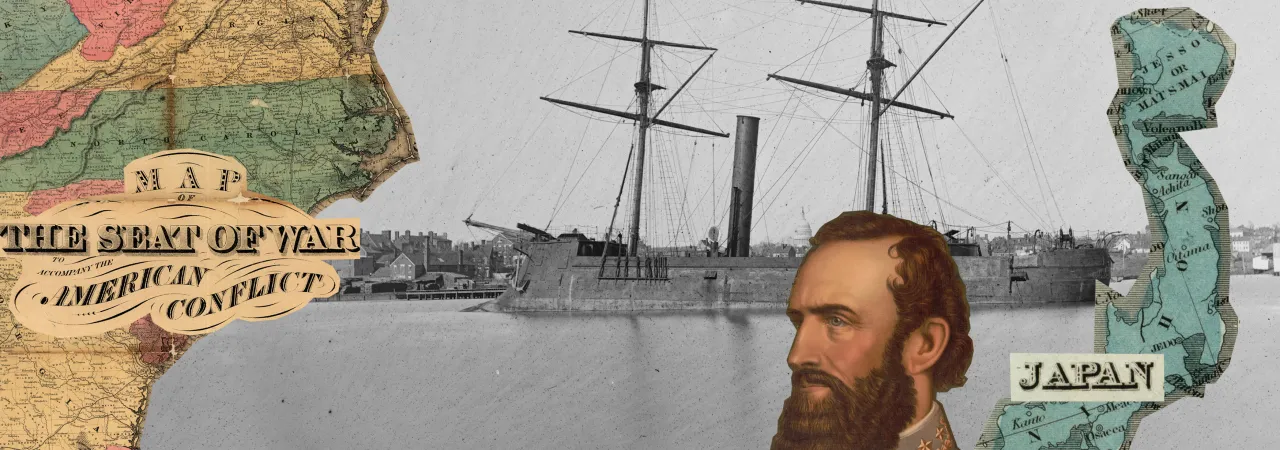

The Confederate Ironclad that Secured a Japanese Revolution

When cutting edge naval technology misses the conflict it was built for, sometimes it ends up securing a revolution on the other side of the world.

Updated September 7, 2023 • February 24, 2020

Sign up for our quarterly email series of curated stories for the curious-minded sort!Contact InformationFirst NameLast NameEmail Address

In the early days of 1865, French shipbuilder Lucien Arman sold the Confederate Navy one of the deadliest vessels ever built up to that point in history. The Confederates named the ship the CSS Stonewall, and their brief time at its helm marked the start of 23 years of service on the shores of three continents.

The Stonewall had its first triumph before even setting off for the Americas, when its new Confederate crew stopped in Spain for much-needed repairs after a storm. During the Stonewall’s seven weeks docked in Spain, Union representatives continuously lobbied the Spanish government to cease the repairs and assigned two ships to monitor the situation. Yet, when the renovated Stonewall was finally ready to cross the Atlantic, the Union ships, intimidated by the powerful vessel, reluctantly allowed it to pass without a fight.

Upon arrival in Havana, Cuba, the CSS Stonewall’s captain received some troubling news: the Union had won the war. He opted to sell the Stonewall to Spanish colonial officials for $16,000 – enough to pay his crew and see everyone home. The Spanish officials quickly sold the vessel to the U.S. government for around the amount they’d paid for it. The ship then sat in the Washington Navy Yard in the nation’s capital for several years before catching the eye of Japan’s feudal lords, the Tokugawa Shogunate, who hoped to hold onto power by upgrading their navy. The Shogunate purchased the Stonewall, but by the time the ship saw combat in Japan, it was actually serving under the Shogunate’s adversaries, who had successfully taken control of the country. The ship was renamed the Kōtetsu, then, later, the Azuma, and it served Japan’s new Meiji government until it was retired from the Japanese fleet in 1888.

So, what was it about the CSS Stonewall that inspired such fear and admiration? Here’s a breakdown of what made this ironclad so exceptional for its time.

The Armor

Perhaps the most innovative characteristic of ironclads (and the inspiration for their name) was the armor that protected them from enemy artillery. Well-constructed ironclads could withstand tremendous fire, rendering previously deadly weapons practically useless and upsetting the ancient naval axiom that forts are stronger than ships. The Stonewall featured iron plating with thickness ranging from 3.5 to 5-inches extending a full 5 feet below the waterline, as well as some 5-inches of iron armor in the front and back of ship that offered extra protection to artillery and crew.

The Ram

The Stonewall was born in a fleeting period when armored vessels had become the pinnacle of naval innovation and armor piercing shells hadn’t been invented yet. Rams, an ancient naval technology, made a brief comeback as designers realized the increased maneuverability of a steam engine combined with defensive armor meant one ship could get close enough to smash into and sink another – even another ironclad. In fact, it’s likely that the wood-hulled Union ships guarding the Stonewall during its stop in Spain declined to engage for fear of this prospect. The Stonewall’s ram created a menacing impression but also caused the vessel to handle clumsily when traveling at speed.

The Steam

The age of ironclads would not have been possible without innovations in steam propulsion to allow vessels to navigate with such heavy armor. The Stonewall itself was sail-assisted, allowing it to conserve coal over long distances by using sails when conditions were right. Twin screws and twin rudders allowed for precise steering, including rapid turning, in calm waters.

The Guns

While the Stonewall’s guns were not its most impressive feature, they were nothing to scoff at either. The vessel carried two 70-pounder Armstrong guns, fixed armored turrets containing muzzle-loading pivot guns that could be pointed out of any of several gun ports, and one massive, turreted 300 pounder. At the start of the ship’s tenure at the head of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the newly renamed Kōtetsu famously repelled a surprise attack at the Battle of Miyako Bay largely thanks to a Gatling Gun, a precursor to the machine gun.

Ultimately, Lucien Arman’s remarkable feat of engineering helped shape the fate of a nation – just not the nation it was originally designed for. The vessel was cutting edge even by Western standards, but as Japan’s first ironclad it proved a gamechanger and kingmaker, suppressing several rebellions and serving the Meiji Navy for nearly two decades. By the time this ship of many names retired in 1888, it had helped steam Japan right into the modern era, with all the progress and strife that era would bring.

If the story of the CSS Stonewall leaves you wanting more, watch this In4 video for more about naval technology in the Civil War, then learn more about Navies in America’s Wars.

Leave a comment