What is evident, the Fake President of the United States tried a Business Solution to get a Terrorist Leader to stop bombing Civilian Targets. All this disgusting praise from our FP was for their Mutual Art of the Deal. This Evil Business Postering has a precedence in American History, with the behind the scenes political support of John Astor, especially by Senator Thomas Hart Benton, who was Astor’s attorney before he got elected Senator of Missouri. How much contact Benton had with Russians in Alaska and California, is now a valuable study, because NATO members in Canada and Europe want to see the IDIOTIC DILUSSINON OF A BUSINESS MADMAN, who thinks our troops can be used – like a king or Roman Emperor, would use troops.

John Presco ‘New Puritan Leader’

The first face-to-face meeting in years between US President Donald Trump and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin was marked by a viral image that drew sharp reactions online.

Before Putin descended from his aircraft at a US air base in Alaska, American soldiers were seen kneeling at the foot of the stairs to adjust the red carpet rolled out for him.

Thomas Hart Benton and Oregon

By Jim Scheppke

As a newspaper editor and then as a United States senator for Missouri for three decades, Thomas Hart Benton was a champion for the American colonization of the Oregon Country during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Born in North Carolina in 1782, Benton’s family moved to a homestead in Tennessee in 1801. At age twenty-four, he opened a law practice in Nashville and was elected to the state senate. In 1815, after serving in the War of 1812, he relocated to St. Louis, where he practiced law and became acquainted with William Clark, who had been appointed governor of Missouri Territory, and fur trappers and traders, from whom he learned about the potential of the Oregon Country.

From 1818 to 1820, Benton edited the St. Louis Enquirer, which he used as a platform to advocate for Oregon occupation. He shared his concerns about the 1818 joint occupation agreement of the Oregon Country between Great Britain and the United States, because he feared losing Oregon if a treaty granting U.S. possession was not achieved. He promoted colonization of the region and reported that Oregon could support a rich economy of “furs and bread.” His vision included a trading connection that would benefit St. Louis.

Benton was elected by the General Assembly to serve as one of Missouri’s first two U.S. senators in 1820 (Missouri had been admitted to the Union as a slave state as part of the 1820 Missouri Compromise; its statehood was ratified on August 10, 1821). He wasted no time speaking in favor of a bill during a session in January 1821 to “authorize the occupation of the Columbia River and to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indian tribes therein.” While the bill drew little support, “the first blow was struck,” Benton later wrote in his memoirs.

The Oregon Question, as it came to be known, was debated often in the Senate, with Benton as one of Oregon’s strongest supporters. In 1833, he acquired an important ally, Missouri Senator Lewis Linn, and the two men worked closely together to advance proposals for federal involvement in the Oregon Country. A bill introduced by Linn shortly before his death in 1843 would have established forts from St. Louis to the mouth of the Columbia, provided land grants, and extended legal jurisdiction from Iowa Territory to the Pacific. The bill passed the Senate but failed in the House.

In 1842, Benton promoted a U.S. Army expedition led by his son-in-law, Lieutenant John C. Frémont, to map the Oregon Trail from Missouri to South Pass in present-day Wyoming. Frémont and his wife, Jessie Benton, collaborated on a report of the expedition that achieved wide readership and stimulated considerable interest in Oregon resettlement.

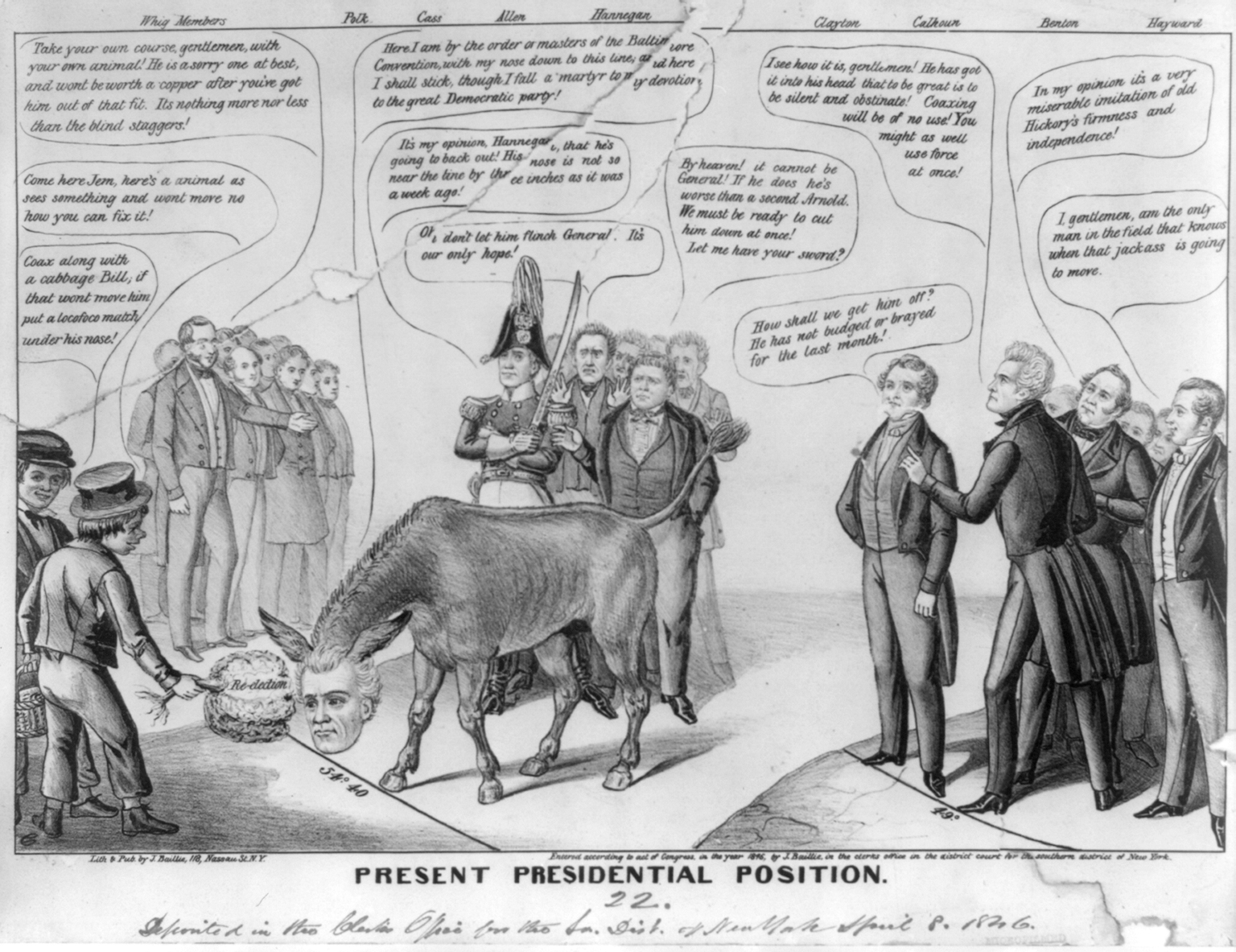

By 1844, more than 2,600 people had emigrated to the Oregon Country, and the time had come, Benton judged, for action that he had advocated for decades. James K. Polk’s expansionist platform in the 1844 presidential campaign focused prominently on Oregon for inclusion in the American republic. Although some expansionists demanded that the United States take possession of the entire Oregon Country by force of arms against the British if necessary—the “54-40 or Fight” threat, which referred to the area’s northern-most boundary line—Benton had long favored the 49th parallel as a more reasonable boundary. He worked closely with President Polk on negotiations with the British and in June 1846 successfully led the Senate debate that gained approval for the Oregon Treaty. The treaty ended joint occupation with Britain and gave the U.S. possession of the Oregon Country to the 49th parallel, which marks today’s U.S./Canada border.

Benton also led the effort to pass a bill establishing Oregon as a U.S. territory in 1848. From the start, the proposal was caught up in the slavery issue. The Oregon Provisional Government had outlawed slavery but had also passed exclusion laws, blocking the residency of free Blacks. Though Benton was a Southerner and a slave owner from a slave state, he was also a Free Soiler who worked against the expansion of slavery to “protect” free white labor in the West, and he did so in the case of Oregon. His frustration spilled over in debate: “We can see nothing, touch nothing, have no measures proposed, without having this pestilence [slavery] thrust before us.” Only hours before the close of the 30th Congress, Benton’s motion to pass the House version of the bill that left standing the exclusion of slavery in Oregon succeeded by a vote of 29 to 20. He was one of only two Southern senators who voted for the bill.

In 1851, Benton’s controversial positions on the Oregon Country’s northern boundary and on the extension of slavery to the new territory likely contributed to his being replaced after thirty years in the Senate. He died seven years later, on April 10, 1858. Benton County, named for Benton in 1847 by the Oregon Provisional Legislature, honors a man who, at crucial times, was a persuasive advocate for the Oregon Territory.

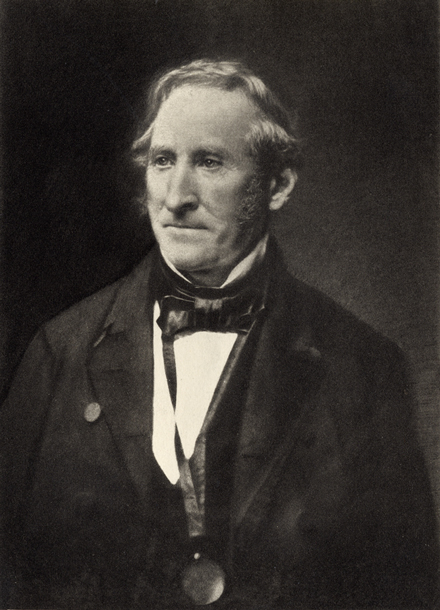

Zoom imageThomas Hart Benton. Courtesy U.S. Senate

Zoom imageThomas Hart Benton. Courtesy U.S. Senate Zoom image”Present Presidential Position,” 1846. A political cartoon illustrating the debate over the Oregon Question: briefly, Pres. Polk stubbornly clings to the 54’40” boundary line for Oregon Country, risking war with Great Britain over region that had been jointly occupied by the two countries. Benton is shown to the right advocating for the 49th parallel (today’s border with Canada). Courtesy Library of Congress

Zoom image”Present Presidential Position,” 1846. A political cartoon illustrating the debate over the Oregon Question: briefly, Pres. Polk stubbornly clings to the 54’40” boundary line for Oregon Country, risking war with Great Britain over region that had been jointly occupied by the two countries. Benton is shown to the right advocating for the 49th parallel (today’s border with Canada). Courtesy Library of Congress

The American Fur Company (AFC) was a prominent American company that sold furs, skins, and buffalo robes.[1][2] It was founded in 1808 by John Jacob Astor, a German immigrant to the United States.[3] During its heyday in the early 19th century, the company dominated the American fur trade. The company went bankrupt in 1842 and was dissolved in 1847.

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Fur trade |

| Founded | 1808; 217 years ago, in New York City, United States |

| Founder | John Jacob Astor |

| Defunct | 1847 |

| Fate | Dissolved |

| Headquarters | New York City |

| Area served | United States and Territories |

During the 18th century, furs had become a major commodity in Europe, and Indigenous people in North America became a major supplier. Several British companies, most notably the North West Company (NWC) and the Hudson’s Bay Company, competed against Astor and capitalized on the lucrative trade in furs. Astor used a variety of commercial strategies to become one of the first trusts in American business and a major competitor to the British commercial dominance in North American fur trade.[1] Expanding into many former British fur-trapping regions and trade routes, the company grew to monopolize the fur trade in the United States by 1830, and became one of the largest and wealthiest businesses in the country.

Astor planned for several companies to function across the Great Lakes, the Great Plains and the Oregon Country to gain control of the North American fur trade. Comparatively inexpensive manufactured goods were to be shipped to commercial stations for trade with various Indigenous nations for fur pelts. The sizable number of furs collected were then to be brought to the port of Canton, as pelts were in high demand in the Qing Empire. Chinese products were, in turn, to be purchased for resale throughout Europe and the United States. A beneficial agreement with the Russian-American Company was also planned through the regular supply of provisions for posts in Russian America. This was planned in part to prevent the rival Montreal based NWC to gain a presence along the Pacific Coast, a prospect neither the Russian colonial authorities nor Astor favored.[4]

Demand for furs in Europe began to decline during the early 19th century, leading to the stagnation of the fur trade by the mid-19th century. Astor left his company in 1830, the company declared bankruptcy in 1842, and the American Fur Company ultimately ceased trading in 1847.

Background

Origin

Both Alexander Mackenzie and Alexander Henry advocated for trade posts on the Pacific Coast, influencing Astor’s decision to establish the PFC.

Before John Jacob Astor founded his enterprise in the Oregon Country, European descendants throughout previous decades had suggested creating trade stations along the Pacific Coast. Peter Pond, an active American fur trader, offered maps of his explorations in modern Alberta, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories to both the United States Congress and to Henry Hamilton, Lieutenant Governor of Quebec in 1785. While it has been conjectured that Pond wanted funding from the Americans to explore the Pacific Coast for the Northwest Passage,[5] there is no documentation of this and it is more likely that he had sent a copy of the map to Congress due to personal pride.[6] Pond later became a founding member of the North West Company (NWC) and continued to trade in modern Alberta.

In time Pond had an influence upon Alexander Mackenzie, who later crossed the North American continent.[6] In 1802, Mackenzie promoted a plan form the “Fishery and Fur Company” to the British government. In it he called for “a supreme Civil & Military Establishment” on Nootka Island, with two additional posts located on the Columbia River and another in the Alexander Archipelago.[7] Additionally this plan was formed to bypass the three major British monopolies at the time, the Hudson’s Bay Company, the South Sea Company and the East India Company for access the Chinese markets.[7] However the British government turned down the offer, leaving the NWC to pursue MacKenzie’s plans alone.[5] Another likely influence upon Astor was a longtime friend, Alexander Henry. At times Henry mused at the potential of the western coast. Forming establishments on the Pacific shoreline to harness the economic potential would be “my favorite plan” as Henry described in a letter to a New York merchant.[8] It is likely that these considerations were discussed with Astor during his visits to Montreal and the Beaver Club. Despite not originating the idea to create a venture on the Pacific coast, Astor’s “ability to combine and use the ideas of other men”[8] allowed him to pursue the idea.

China trade

Astor joined in on two NWC voyages charted to sail to the Qing Empire during the 1790s. These were done with American vessels to bypass British commercial law, which at the time prohibited any company besides the East India Company from commerce with China. These were financially profitable ventures, enough so that Astor offered to become the NWC agent for all shipments of furs destined for Guangzhou. However Alexander Mackenzie denied his offer, making Astor consider financing voyages to China without the Canadian traders.[9] Now a fully independent international merchant, Astor began to fund trading voyages to China along with several partners. Cargoes often amounted to $150,000 (equivalent to about $4 million in 2024) in such as otter and beaver pelts, in addition to needed specie. Astor ordered the construction of the Beaver in 1803 to expand his trade fleet.[10]

Chicago Outfit

Formation

By the early 1800s the Chicago area was already a large center for the fur trade. The city was largely occupied by soldiers stationed at Fort Dearborn and fur traders in small camps.[11] Prior to the War of 1812 the British maintained control of the area. However, in 1811 John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company began to lay the foundation to move into the area.[11] This foundation began with a partnership between the American Fur Company and two British companies that supplied trade goods to the Chicago area. The terms of this arrangement were such that the partnership would last for five years or until the American government prohibited the use of foreign capital in the United States.[11] This partnership was short lived as after the War of 1812 the United States government banned foreign investors from entering the United States and engaging in trade with Native Americans. Congress passed this law at the urging of John Jacob Astor with the caveat that a special exemption to this law could be granted exclusively by the president. Later this power would be given to Native American tribes and some territorial officials.[12] One years time was enough that John Jacob Astor and the American Fur Company has sufficient connections in the area to fill the void left by the banning of the British Companies that formerly held control of the Chicago fur trade.

Information

By 1808, Astor had established “an international empire that mixed furs, teas, and silks and penetrated markets on three continents.”[10] He began to court diplomatic and government support of a fur trading venture to be established on the Pacific shore in the same year. In correspondence with the Mayor of New York City, DeWitt Clinton, Astor explained that a state charter would offer a particular level of formal sanction needed in the venture.[5] He in turn requested the Federal government grant his operations military support to defend against Indians and control these new markets. The bold proposals were not given official sanction however, making Astor to continue to promote his ideas among prominent governmental agents.

President Thomas Jefferson was contacted by the ambitious merchant as well. Astor gave a detailed plan of his mercantile considerations, declaring that they were designed to bring about American commercial dominance over “the greater part of the fur-trade of this continent…”[5] This was to be accomplished through a chain of interconnected trading posts that stretching across the Great Lakes, the Missouri River basin, the Rocky Mountains, and ending with a fort at the entrance of the Columbia River.[13] Once the pelts were collected from the extensive outposts they were to be loaded and shipped aboard ships owned by Astor to the Chinese port of Guangzhou, where furs were sold for impressive profits. Chinese products like porcelain, nankeens and tea were to be purchased; with the ships then to cross the Indian Ocean and head for European and American markets to sell the Chinese wares.[14]

Subsidiaries

Pacific Fur Company

Main article: Pacific Fur Company

To begin his plans of a chain of trading stations spread across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Northwest, Astor incorporated the AFC subsidiary, the Pacific Fur Company.[15][16] Astor and the partners met in New York on 23 June 1810 and signed the Pacific Fur Company’s provisional agreement.[17] The fellow partners were former NWC men, being Alexander McKay, Duncan McDougall, and Donald Mackenzie. The chief representative of Astor in the daily operations was Wilson Price Hunt, a St. Louis businessman with no outback experience.[16]

From the outpost on the Columbia, Astor hoped to gain a commercial foothold in Russian America and China.[14] In particular, the ongoing supply issues faced by the Russian-American Company were seen as a means to gain yet more furs.[18] Cargo ships en route from the Columbia were planned to then sail north for Russian America to bring much needed provisions.[14] By cooperating with Russian colonial authorities to strengthen their material presence in Russian America, it was hoped by Astor to stop the NWC or any other British presence to be established upon the Pacific Coast.[4] A tentative agreement for merchant vessels owned by Astor to ship furs gathered in Russian America into the Qing Empire was signed in 1812.[18]

While intended to gain control of the regional fur trade, the Pacific Fur Company floundered in the War of 1812. The possibility of an occupation by the Royal Navy forced the sale of all company assets across the Oregon Country. This was formalized on 23 October 1813 with the raising of the Union Jack at Fort Astoria.[19] On 30 November HMS Racoon arrived at the Columbia River and in honor of George III of the United Kingdom, Fort Astoria was renamed Fort George.[20] After the forced merger in 1821 of the North West Company into their long time rivals, the Hudson’s Bay Company, in a short time the HBC controlled the majority of the fur trade across the Pacific Northwest. This was done in a manner that “the Americans were forced to acknowledge that Astor’s dream” of a multi-continent economic web “had been realized… by his enterprising and far-sighted competitors.”[21]

South West Company

The South West Company handled the Midwestern and Southwestern fur trade. In the Midwest, it also competed with regional companies along the upper Missouri, upper Mississippi, Platte rivers and as far south as New Mexico. These competitors were mostly companies based in Saint Louis, Missouri, which were active in the fur trade as well as in trade of general merchandise, and which were typically founded and led by French colonial families, such as Pratte, Chouteau, Cabanne and Ceran St. Vrain amongst the most prominent, both before and after the Louisiana Purchase or Astor setting up his company. Competition in the wilderness areas between men of the companies sometimes erupted into physical violence and outright attacks.[22] In 1834, the American Fur Company sold its Western Division to Bernard Pratte and Pierre Chouteau Jr., with whom they had been already cooperating, with the latter continuing the business as Pratte, Chouteau & Company.

Later history

For a time, it seemed that the company had been destroyed but, following the war, the United States passed a law excluding foreign traders from operating on U.S. territory. This freed the American Fur Company from having to compete with the Canadian and British companies, particularly along the borders around the Great Lakes and in the West. The AFC competed fiercely among American companies to establish a monopoly in the Great Lakes region and the Midwest. In the 1820s the AFC expanded its monopoly into the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains, dominating the fur trade in what became Montana by the mid-1830s.[23] To achieve control of the industry, the company bought out or beat out many smaller competitors, like the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

By 1830, the AFC had nearly complete control of the fur trade in the United States. The company’s time at the top of America’s business world was short-lived. Sensing the eventual decline of fur’s popularity in fashion, John Jacob Astor withdrew from the company in 1834. The company split into smaller entities like the Pacific Fur Company. The Northern Division of the midwestern outfit continued to be called the American Fur Company and was led by Ramsay Crooks. To cut down on expenses, it began closing many of its trading posts.

Decline

Through the 1830s, competition began to resurface. At the same time, the availability of furs in the Midwest declined. During this period, the Hudson’s Bay Company began an effort to destroy the American fur companies from its Columbia District headquarters at Fort Vancouver. By depleting furs in the Snake River country and underselling the American Fur Company at the annual Rocky Mountain Rendezvous, the HBC effectively ruined American fur trading efforts in the Rocky Mountains.[24] By the 1840s, silk was replacing fur for hats as the clothing fashion in Europe. The company was unable to cope with all these factors. Despite efforts to increase profits by diversifying into other industries like lead mining, the American Fur Company folded. The assets of the company were split into several smaller operations, most of which failed by the 1850s. In 1834, John Jacob Astor sold his interest on the river to replace the old fur company. He invested his fortune in real estate on Manhattan Island, New York, and became the wealthiest man in America. After 1840, the business of the American Fur Company declined.

Leave a comment