The Royal Janitor

by

John Presco

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

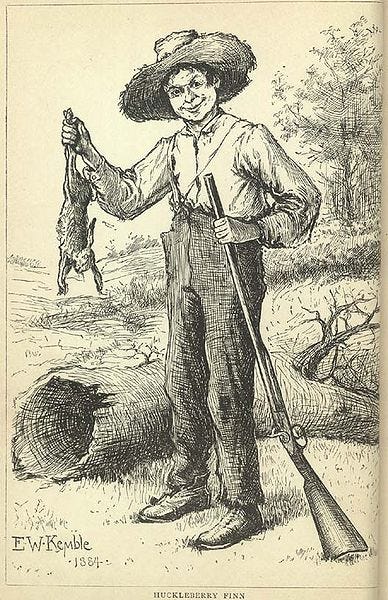

Victoria Rosemond began to do her genealogy at the College of Arms when she was nine. She started with John Egerton, 3rd Earl of Bridgewater First Lord of the Admiralty, because her mother allowed the world this much information about who her daughter was, other than the granddaughter of James Bond. As for her middle name, Rosemond, she found a smattering of Clodhoppers and Hillbillys down south, and in the Ozarks. When she read Duke of Bridgewater was in Huckleberry Fynn, she got the book and read it. She had a difficult time with the vernacular literary tradition that was picked up by several author, one them; Royal Rosamond. He failed at this, miserably, and his wife had his four daughter put his books in a pyre, and burn them. Mary Magdalene dressed her daughters in Native American costumes and make a war whoop. What came out of them was……. a circle of tears.

:”How sad! How pathetic. This is what you get when the colonies lift the history of Kings! To put Ashridge House in Arkansas, even if in a literary fashion, is a insult to the British Empire!”

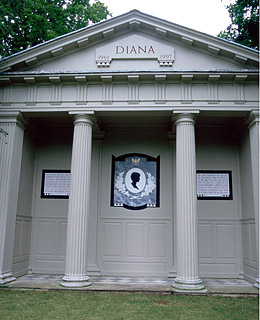

Victoria quit working on her genealogy – in disgust! Which is a shame. Can you see who she missed? If Victoria had kept going she would have discovered she is third cousin to Princess Diana Spenser. I found this out at 4:30 PM on July 29, 2025, after I wondered if Mark Twain met two pretenders to the throne, one of France, and the other of England. Princess Diana’s second son, lives in America, still?

This discovery makes Mark Twain on of the most prophetic authors in American – and British History! What does this make, the Creator of Victory Rosemond Bond? Is Victoria Rosemond Bond – in line for the thrown of England? Or, did this linage become extant? What is truly going on here!

Princess Di will forever be in the hearts of millions of Americans, and in the hearts of the lovers of Mark Twain, thanks to the grandson of……Royal Rosamond!

“What is in a name?” There is another hidden author in the gardens of Asnridge House. Can you find…

Her?

JRP

The surviving son of John Egerton, 1st Earl of Bridgewater, and his wife Lady Frances Stanley, his maternal grandparents were Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby, and Lady Alice Spencer. According to the Will of King Henry VIII, his mother, at one time, was second-in-line to inherit England’s throne. However, Frances, Countess of Bridgewater’s elder sister, Lady Anne Stanley, was passed over in favour of King James VI of Scotland.

(Redirected from Alice Spencer)

| Alice Spencer | |

|---|---|

| Countess of Derby Baroness Ellesmere Viscountess Brackley | |

| Portrait tentatively identified as Alice Spencer, painted by an unknown artist in the circle of Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger | |

| Born | 4 May 1559 Althorp, Northamptonshire, England |

| Died | 23 January 1637 (aged 77) Harefield Place, Middlesex |

| Buried | St Mary the Virgin Church, Harefield |

| Noble family | Spencer |

| Spouse(s) | Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby Thomas Egerton, 1st Viscount Brackley |

| Issue | Anne Stanley, Countess of Castlehaven Frances Egerton, Countess of Bridgewater Elizabeth Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon |

| Father | Sir John Spencer |

| Mother | Katherine Kytson |

Alice Spencer, Countess of Derby (4 May 1559 – 23 January 1637) was an English noblewoman from the Spencer family and noted patron of the arts. Poet Edmund Spenser represented her as “Amaryllis” in his eclogue Colin Clouts Come Home Againe (1595) and dedicated his poem The Teares of the Muses (1591) to her.

Her first husband was Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby, a claimant to the English throne. Alice’s eldest daughter, Anne Stanley, Countess of Castlehaven, was heiress presumptive to Queen Elizabeth I. She married secondly in 1600 Thomas Egerton, 1st Viscount Brackley and thus became a member of the Egerton family.[1]

Family

Alice was born in Althorp, Northamptonshire, England on 4 May 1559, the youngest daughter of Sir John Spencer,[2] member of parliament and high sheriff of Northamptonshire, and Katherine Kytson. She had three brothers and three older sisters. [citation

The Maze and Grail At Blenheim Palace

Posted on April 18, 2013 by Royal Rosamond Press

The estate given by the nation to Marlborough for the new palace was the manor of Woodstock, sometimes called the Palace of Woodstock, which had been a royal demesne, in reality little more than a deer park. Legend has obscured the manor’s origins. King Henry I enclosed the park to contain the deer. Henry II housed his mistress Rosamund Clifford (sometimes known as “Fair Rosamund”) there in a “bower and labyrinth”; a spring where she is said to have bathed remains, named after her. It seems the unostentatious hunting lodge was rebuilt many times

Jim and Huck fall for the two and “set to majestying” Dauphin to make him feel better, which “kind of soured” the Duke. Huck figures out in short order, however, that the two are not who they said, explaining that “If I never learnt nothing else out of pap, I learnt tht the best way to get along with his kind of people is to let them have their own way.”

| The Duke of “Bilgewater” shakes hands “Looy the Seventeen” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gQTkywDkZ64 |

(Redirected from Duke of Bridgewater)

Earl of Bridgewater was a title that has been created twice in the Peerage of England, once for the Daubeny family (1538) and once for the Egerton family (1617). From 1720 to 1803, the Earls of Bridgewater also held the title of Duke of Bridgewater. The 3rd Duke of Bridgewater is famously known as the “Canal Duke”, for his creation of a series of canals in North West England.

History

Creation for the Daubeny family (1538)

The title Earl of Bridgewater was first created in 1538 for Henry Daubeny, 9th Baron Daubeny. The Daubeney (or Dabney[1]) family descended from Elias Daubeny, who in 1295 was summoned by writ to the Model Parliament as Lord Daubeny. The eighth Baron was created Baron Daubeny by letters patent in the Peerage of England in 1486 and was also made a Knight of the Garter the following year. All three titles became extinct on the first Earl of Bridgewater’s death in 1548.

Creation for the Egerton family (1617)

The title Earl of Bridgewater was created secondly in 1617 for John Egerton, Baron Ellesmere and Viscount Brackley, after the town of Bridgwater in Somerset, where he owned estates.[2] The Egerton family descended from Sir Richard Egerton of Ridley, Cheshire, whose illegitimate son Sir Thomas Egerton was a prominent lawyer who served as Master of the Rolls from 1594 to 1603, as Lord Keeper of the Great Seal from 1593 to 1603 and as Lord High Chancellor of England from 1603 to 1617. Thomas Egerton was knighted in 1594, admitted to the Privy Council in 1596 and in 1603 he was raised to the Peerage of England as Baron Ellesmere, in the County of Shropshire, and in 1616 to Viscount Brackley. In 1598 he had inherited the Tatton estate in Cheshire from his brother-in-law Richard Brereton. He was succeeded by his son, John who represented Callington and Shropshire in the House of Commons and served as Lord-Lieutenant of several counties in Wales and western England and who in 1617 was made Earl of Bridgewater in the Peerage of England.

He was succeeded by his eldest surviving son, the second Earl. He was Lord-Lieutenant of Buckinghamshire, Lancashire, Cheshire and Herefordshire. On his death the titles passed to his eldest son, the third Earl. He was a Whig politician and served as First Lord of Trade and as First Lord of the Admiralty. His eldest son from his first marriage, John Egerton, died as an infant, while his two elder sons from his second marriage, Charles Egerton, Viscount Brackley, and the Hon. Thomas Egerton, both died in the fire which destroyed Bridgwater House in London. Lord Bridgewater was succeeded by his eldest surviving son from his second marriage, the fourth Earl. He served as Lord-Lieutenant of Buckinghamshire and also held several positions at court. In 1720 he was created Marquess of Brackley, in the County of Northampton, and Duke of Bridgewater, in the County of Somerset. Both titles were in the Peerage of Great Britain.

The first Duke outlived his two elder sons and was succeeded by his second but eldest surviving son from his second marriage, the second Duke. He died from fever at an early age. On his death the titles passed to his younger brother, the third Duke. He is remembered as the father of British inland navigation and commissioned the Bridgewater Canal, said to be the first true canal in Britain and the modern world. Bridgewater never married and on his death in 1803 the marquessate and dukedom became extinct.

The last Duke was succeeded in the other titles by his first cousin once removed, the seventh Earl. He was the son of the Right Reverend the Hon. John Egerton, Bishop of Durham, son of the Right Reverend the Hon. Henry Egerton, Bishop of Hereford, youngest son of the third Earl. Lord Bridgewater was a General in the Army and also sat as Tory Member of Parliament for Morpeth and for Brackley. He was childless and on his death in 1823 the titles passed to his younger brother, the eighth Earl. He was known as a patron of science as well as a great eccentric. Lord Bridgewater never married and on his death in 1829 his titles became extinct.

In the early 17th century, Thomas Egerton, 1st Viscount Brackley, had purchased Ashridge House in Hertfordshire, one of the largest country houses in England, from Queen Elizabeth I, who had inherited it from her father who had appropriated it after the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539. Ashridge House served the Egerton family as a residence until the 19th century. The Egertons later had a family chapel (the Bridgewater Chapel) with burial vault in Little Gaddesden Church, where many monuments commemorate the Dukes and Earls of Bridgewater and their families.[3] Among those buried here is the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater.[4]

Lady Amelia Egerton, sister of the seventh and eighth Earls, married Sir Abraham Hume, 2nd Baronet. Their daughter Sophia Hume married John Cust, 1st Earl Brownlow. Their grandson John William Spencer Brownlow Egerton-Cust, 2nd Earl Brownlow (1842–1867), assumed the additional surname of Egerton and inherited the Bridgewater estates after a lengthy lawsuit (see the Baron Brownlow for additional information on the Cust family). Also, Lady Louisa Egerton, daughter of the first Duke of Bridgewater, married Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st Marquess of Stafford. Their son George Leveson-Gower, 2nd Marquess of Stafford, was created Duke of Sutherland in 1833. His second son Lord Francis Leveson-Gower assumed by Royal licence the surname of Egerton in lieu of Leveson-Gower according to the will of the third Duke of Bridgewater. In 1846 the Brackley and Ellesmere titles were revived when he was made Viscount Brackley and Earl of Ellesmere. The Hon. Thomas Egerton, of Tatton Park, Cheshire, youngest son of the second Earl of Bridgewater, was the grandfather of Hester Egerton (d. 1780). She married William Tatton. In 1780 they assumed by Royal licence the surname of Egerton in lieu of Tatton. Their great-grandson William Tatton Egerton was created Baron Egerton in 1859.

A scoundrel claiming to be the long-lost but rightful Duke of Bridgewater appears in the 1885 novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, which is set before the American Civil War.

The original spelling is likely to have been Bridgwater, meaning the burg of Water, and the same as Bridgwater in Somerset (see archive reference 2/79).

Holders of the title

Daubeny family

Barons Daubeney (1486)

- Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney (d. 1508)

- Henry Daubeney, 2nd Baron Daubeney (1494–1548) (created Earl of Bridgewater in 1538)

Earls of Bridgewater, First Creation (1538)

- Henry Daubeney, 1st Earl of Bridgewater (1493–1548)

Egerton family

Main article: Egerton family

Earls of Bridgewater, Second Creation (1617)

Other titles: Baron Ellesmere (1603) and Viscount Brackley (1616)

- John Egerton, 1st Earl of Bridgewater, 2nd Viscount Brackley (1579–1649), second son of Thomas Egerton, 1st Viscount Brackley and 1st Baron Ellesmere

- James Egerton, Viscount Brackley (1616–1620), his eldest son, who died in childhood

- Charles Egerton, Viscount Brackley (c. 1617–1623), his next brother, who also died in childhood

- John Egerton, 2nd Earl of Bridgewater (1623–1686), his only adult brother

- John Egerton, 3rd Earl of Bridgewater (1646–1701), his eldest son

- Hon. John Egerton (1669–1670), his eldest son, who died in infancy

- Charles Egerton, Viscount Brackley (1675–1687), his younger half-brother, who died in childhood

- Scroop Egerton, 4th Earl of Bridgewater (1681–1745), his younger brother, who was created Duke of Bridgewater and Marquess of Brackley in 1720

- John Egerton, Viscount Brackley (1704–1719), his eldest son, who died before adulthood

Dukes of Bridgewater (1720)

Other titles: Baron Ellesmere (1603), Viscount Brackley (1616), Earl of Bridgewater (1617) and Marquess of Brackley (1720)

- Scroop Egerton, 1st Duke of Bridgewater, 4th Earl of Bridgewater (1681–1745)

- John Egerton, 2nd Duke of Bridgewater, 5th Earl of Bridgewater (1727–1748), his son, who died young and unmarried

- Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, 6th Earl of Bridgewater (1736–1803), his younger brother, who also died unmarried

Earls of Bridgewater, Second creation (1617; Reverted)

Other titles: Baron Ellesmere (1603) and Viscount Brackley (1616)

- John William Egerton, 7th Earl of Bridgewater (1753–1823), great-grandson of the 3rd Earl (via John Egerton, Bishop of Durham, and Henry Egerton, Bishop of Hereford)

- Francis Henry Egerton, 8th Earl of Bridgewater (1756–1829), his younger brother, who died without heirs

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: The Duke & King

Zack KulmFollow

8 min read

·

Apr 16, 2021

“Let the cold world do its worst; one thing I know — there’s a grave somewhere for me. The world may go on just as it’s always done, and take everything from me — loved ones, property, everything — but it can’t take that. Some day I’ll lie down in it and forget it all, and my poor broken heart will be at rest.”

So says the self-proclaimed ‘Duke of Bridgewater’ as he introduces himself to Huck and Jim in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn the direct sequel of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The work is among the first in American literature to be written throughout in vernacular English, characterized by local color regionalism. The book is set in a Southern antebellum society and is known to be a scathing satire on entrenched attitudes, particularly racism, as well as for its colorful descriptions of people and places along the Mississippi River.

As the Duke tells a sad tale of his hopeless circumstances, with him is his companion who shares a similar pitiful tale, even going so far as to one-up him. His companion is an older man in his 70s who claims to be the self-styled ‘dauphin, Louis XVII,’ going on to say:

“Yes, gentlemen, you see before you, in blue jeans and misery, the wanderin’, exiled, trampled-on and sufferin’ rightful King of France.”

Keep reading for a deep dive into the infamous conmen, the Duke and King in Mark Twain’s great American novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Sorry to disappoint you, but these aren’t a real Duke and King. No, they’re grifters out to con the people of more than one riverside town.

The conmen enter the narrative as inconvenient and troublesome as their reputation will soon reveal. After a few peaceful days on the raft, Huck is searching for some berries in a creek when he comes upon two desperate men. The men are obviously being chased, and Huck tells them how to lose the dogs, helping them to escape. The men, one around 70 and the other around 30 years old, join Huck and Jim on the raft.

Together, the duke and king portray themselves as down-and-out victims in order to curry favor through pity and to conceal their fraudulent intentions. Despite their efforts, Huck believes the men are simple conmen but decides not to challenge them in order to keep the peace.

At first, when the duke and the king first meet, they try to con each other. But they soon strike a truce and go off to con the whole world — or, at least what’s known of it along the Mississippi.

“Like as not we got to be together a blamed long time on this h-yer raft, Bilgewater, and so what’s the use o’ your bein’ sour? It’ll only make things on-comfortable. It ain’t my fault I warn’t born a duke, it ain’t your fault you warn’t born a king — so what’s the use to worry? Make the best o’ things the way you find ’em, says I — that’s my motto. This ain’t no bad thing that we’ve struck here — plenty grub and an easy life — come, give us your hand, duke, and le’s all be friends.”

Talk about meet-cute.

Our first impressions of this duo give us the sense that the Duke holds the higher moral ground of the pair, which really isn’t saying much. Next, we learn that it’s not over friendship or loyalty for one another that they pair up, but rather for “plenty grub and an easy life.” In other words, we wouldn’t bet on this team in Dancing with the Stars.

Okay, but other than serving as examples of What-Not-To-Do, the Duke and King have two significant roles in the novel. First is they’re essentially the bizarro-world version of Huck and Jim, and secondly, they play a major part in Huck’s maturation.

From here, the schemes of the conmen direct the plot. As the duke and king become permanent passengers on Jim and Huck’s raft, committing a series of confidence schemes upon unsuspecting locals. The duke even goes so far as to dress Jim up as an “Arab” to draw less attention and so he can move along the raft without bindings.

Get Zack Kulm’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.Subscribe

They stop in the one-horse town of Pokeville, which is practically deserted because of a nearby camp meeting. When the duke heads off in search of the printing shop, the king decides to attend the meeting. At the meeting, the people sing hymns and go up to the pulpit for forgiveness. It is here where the king professes to be an old pirate who has reformed and seen the error of his ways. Add in some crocodile tears and he’s able to walk away with $87 and a bottle of whiskey. Not too shabby.

The inclusion of the camp meeting is a perfect example of the confidence man. Along with its playful burlesque of religion, the camp meeting shows a gullible audience that is swindled because of its faith. The ensuing scene is reminiscent of George Washington Harris’s “Sut Lovingood’s Lizards” and Johnson J. Hooper’s “Simon Suggs Attends a Camp Meeting.” Both authors were influential for Twain and reflect a society that is scammed because of its misplaced faith or hypocrisy.

“First they done a lecture on temperance; but they didn’t make enough for them both to get drunk on. Then in another village they started a dancing school; but they didn’t know no more how to dance than a kangaroo does; so the first prance they made, the general public jumped in and pranced them out of town. Another time they tried a go a yellocution; but they didn’t yellocute long till the audience got up and give them a solid cussing and made them skip out.”

If the antics of the duke and king weren’t crazy enough, the duke teaches the king Shakespeare which results in their next con — planning a three-night performance called ‘The Royal Nonesuch.’ However, the play turns out to be only a couple of minutes’ worth of an absurd, bawdy sham where a painted, naked king spews nonsense.

By the third night of ‘The Royal Nonesuch’, the townspeople prepare for their revenge. But before they can dish it out the two cleverly skip town together with Huck and Jim just before their performance is to begin.

In the next town, the two swindlers then impersonate the brothers of Peter Wilks, a recently deceased man of property. Mary Jane, Joanna, and Susan Wilks are the three young nieces of their wealthy-deceased guardian. The Duke and the King try to steal their inheritance by posing as Peter’s estranged brothers from England. To match accounts of Wilks’s brothers, the king attempts an English accent and the duke pretends to be a deaf-mute while starting to collect Wilks’s inheritance.

Huck decides that Wilks’s three orphaned nieces, who treat Huck with kindness, do not deserve to be cheated thus and so he tries to retrieve for them the stolen inheritance. In a desperate moment, Huck is forced to hide the money in Wilks’s coffin, which is abruptly buried the next morning.

After the failed attempt to defraud the Wilks nieces, Huck describes the subsequent series of attempted cons by the duke and the king. The tone of the passage is humorous since it shows that the conmen are as inept as they are persistent. But Huck’s words also express a sense of exhaustion and frustration. At this point in the book, he desperately wishes to get away from these increasingly dangerous men.

When the funeral takes place, things become even more complicated when not only is the gold mysteriously found inside the coffin but the real brothers of the dead man show up and get into an argument with the king and the Duke. Huck attempts to get back to the raft and leave without them, but the two villains manage to escape by the skin of their teeth and catch a ride again with Huck and Jim.

At the next town they stop at, the two men inexplicably sell Jim away to some farmers (who later conveniently turn out to be Tom Sawyer’s aunt and uncle), as revenge for Huck ruining their previous scheme.

The King sets Jim up to be captured and uses the $40 reward to get drunk. When pressed, the duke lies to Huck about Jim’s whereabouts, although, to his credit, he almost tells Huck the truth. Making him a little better than the King. At least he’s not a complete sociopath like his older counterpart.

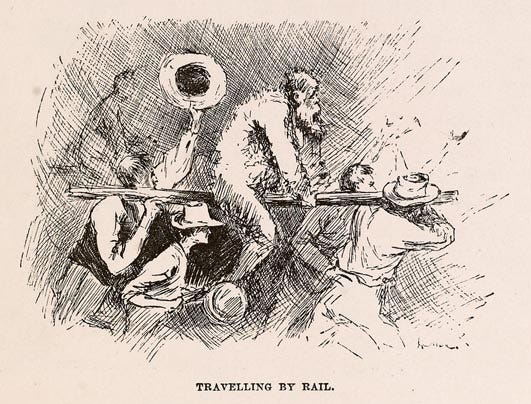

It is not until later when Jim tells the family about the two grifters and the new plan for ‘The Royal Nonesuch’ that the townspeople capture the duke and king, who are deservingly tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on a rail.

The Duke and King serve as an important reminder of what Huck and Jim could become without their morals. At first, Huck is having a grand old time. No rules, no sitting up straight, and definitely no Sunday School. Soon enough, he starts to wonder if maybe life on the lam isn’t so great after all, especially when the king and duke start trying to cheat the Wilk nieces out of their inheritance.

And when the duke and king end up tarred and feathered, Huck realizes that he’s probably better off staying on the right side of the law. And that’s a lesson worthy of royalty. The two are selfish, greedy, deceptive, and debauched, but sometimes their actions expose and exploit societal hypocrisy in a way that is somewhat attractive and also rather revealing. Though the exploits of the duke and king can be farcical and fun to watch, the two demonstrate an absolute, hideous lack of respect for human life and dignity.

At first, the men appear harmless, and Huck quietly rejects their preposterous claims of royalty. His recognition of their true character is important, for he understands that the two pose a particular threat to Jim.

Huck’s insight, however, is not surprising, for the men are simply exaggerations of the characters that Huck and Jim have already encountered during their journey. Huck has learned that society is not to be trusted, and the duke and the king quickly show that his concern is legitimate.

If you haven’t already, make sure to get a copy of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. It’s a book that’s worth multiple readings.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Right HonourableThe Earl of BridgewaterKB PC | |

|---|---|

| First Lord of the Admiralty | |

| In office 1699–1701 | |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Orford |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Pembroke |

| First Lord of Trade | |

| In office 16 December 1695 – 9 June 1699 | |

| Preceded by | Vacant Last held by The Earl of Shaftesbury |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Stamford |

| Member of Parliament for Buckinghamshire With Thomas Warton | |

| In office 1685–1686 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Hampden |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Lee |

| Born | 9 November 1646 |

| Died | 19 March 1701 (aged 54) |

| Spouse(s) | Lady Elizabeth Cranfield(m.1664; died 1668) Lady Jane Paulet (m.1673) |

| Children | 10 |

| Parents | John Egerton, 2nd Earl of Bridgewater (father)Lady Elizabeth Cavendish (mother) |

John Egerton, 3rd Earl of Bridgewater, KB, PC (9 November 1646 – 19 March 1701) was an English politician.

He was the eldest son of John Egerton, 2nd Earl of Bridgewater and his wife Elizabeth Cavendish. His maternal grandparents were William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle and his first wife Elizabeth Basset.

On 17 November 1664, he married Lady Elizabeth Cranfield, daughter of James Cranfield, 2nd Earl of Middlesex. She gave birth to a son, but died in childbirth. He married his second wife on 2 April 1673, Lady Jane Paulet, eldest daughter of Charles Paulet, 1st Duke of Bolton.

Egerton served as a Member of Parliament for Buckinghamshire as a Whig for Buckinghamshire from 1685 to 1686. He also served as Lord Lieutenant of Buckinghamshire following his father’s death in 1686 but was dismissed after his first period in office by King James II for refusing to produce a list of Catholics to serve as officers in the English Militia. He was later reinstated to the position when William III came to the throne and James II was forced into exile.

He served as First Lord of Trade in the Convention Parliament, 1690–1691. He was promoted to the cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty by the Whigs in 1699. He served in this position until March 1700/1.

He was chosen as a Speaker for the House of Lords in 1697 and then again for 1701.

Family

He was first married to Elizabeth Cranfield, a daughter of James Cranfield, 2nd Earl of Middlesex and Anne Bourchier. They had only one known child who survived birth:

- John Cranfield (11 January 1668 – 31 March 1670).

On 2 April 1673, Bridgewater married his second wife Jane Paulet. She was a daughter of Charles Paulet, 1st Duke of Bolton and his second wife Mary Scrope. Mary was the eldest illegitimate daughter of Emanuel Scrope, 1st Earl of Sunderland, and his mistress Martha Jones; she became her father’s co-heiress when a brother died childless. They had nine children:

- Charles Egerton, Viscount Brackley (7 May 1675 – April 1687) died at age 11 at Bridgwater House, the Barbican, London, England, burnt to death in the fire which destroyed Bridgwater House. He was buried on 14 April 1687 at Little Gaddesden, Hertfordshire, England.[1]

- Lady Mary Egerton (14 May 1676 – 11 April 1704). Married William Byron, 4th Baron Byron

- Hon. Thomas Egerton (15 August 1679 – April 1687) died at age 7 at Bridgwater House, the Barbican, London, England, burnt to death in the fire which destroyed Bridgwater House. He was buried on 14 April 1687 at Little Gaddesden, Hertfordshire, England.[1]

- Scroop Egerton, 1st Duke of Bridgewater (11 August 1681 – 11 January 1744/5)

- Hon. William Egerton (1684-15 July 1732), MP and soldier

- Hon. Henry Egerton, Bishop of Hereford (10 February 1689 – 1 April 1746). Married Elizabeth Ariana Bentinck, a daughter of William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland and his second wife Jane Martha Temple. They were parents to John Egerton, Bishop of Durham.

- Hon. John Egerton (d. c.1707), a Page of Honour

- Hon. Charles Egerton (d. 7 November 1725). Married Catherine Greville. His wife was a sister of William Greville, 7th Baron Brooke.

- Lady Elizabeth Egerton. Married Thomas Catesby Paget. Her husband was a son of Henry Paget, 1st Earl of Uxbridge and his wife Mary Catesby. They were parents of Henry Paget, 2nd Earl of Uxbridge.

Redirected from Elizabeth Egerton)

| The Right Honourable The Countess of Bridgewater | |

|---|---|

| Countess of Bridgewater | |

| Born | 1626 |

| Died | 14 July 1663 |

| Buried | Ashridge, Hertfordshire |

| Noble family | Cavendish |

| Spouse(s) | John Egerton, 2nd Earl of Bridgewater |

| Issue | John Egerton, 3rd Earl of Bridgewater Sir William Egerton KB Thomas Egerton Charles Egerton MP Elizabeth Egerton |

| Father | William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle |

| Mother | Elizabeth Basset Howard, |

Elizabeth Egerton, Countess of Bridgewater (née Lady Elizabeth Cavendish; 1626 – 14 July 1663) was an English writer[1] who married into the Egerton family.

Biography

Elizabeth Cavendish was encouraged in her literary interests from a young age by her father, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle, himself an author and patron of the arts surrounded by a literary coterie which included Ben Jonson, Thomas Shadwell, and John Dryden. Her works consist of a series of manuscripts, some of which have recently become available in modern editions.

She married John Egerton (Lord Brackley) in 1641, when she was fifteen. Her mother, Elizabeth Bassett, died in 1643, and her father was later remarried to noted writer Margaret Cavendish. William Cavendish and his sons relocated to France during the English Civil War, while Egerton and her sisters Jane and Frances remained at the besieged family seat in Nottinghamshire until 1645 when she relocated to her husband’s home where she was relatively sheltered from the rest of the war. Egerton’s earliest manuscript compilation (Bodl. Oxf., MS Rawl. poet. 16; Yale University, Beinecke Library, Osborn MS b. 233), an anthology of poems and dramas, Poems Songs a Pastorall and a Play by the Right Honorable the Lady Jane Cavendish and Lady Elizabeth Brackley, co-written with her sister, dates from this period. The Concealed Fansyes, the play mentioned in that title, “features two heroines who hold out for and get ‘equall marryage,’ having trained the gallants, Courtley and Praesumption, who were intending to train them.”[2] Egerton’s final manuscript collection, known as the “Loose Papers,” is made up of prayers, meditations, and essays, some written in response to the illness and death of her children — only four of whom survived to adulthood — and some to pregnancy and childbirth:

O Lord, I knowe thou mightest have smothered this my Babe in the wombe, but thou art ever mercyfull, and hast at this time brought us both from greate dangers, and me from the greate torture of childbirth.[3]

Elizabeth Egerton died delivering her tenth child and was buried at Ashridge, Hertfordshire. Her manuscripts are held at the Nottingham University Library, Portland collection (letters); the Bodleian and Beinecke libraries (Poems Songs &c.); and the British and Huntington Libraries (her “Loose Papers”). Her essays on marriage and widowhood “open a highly unusual window on the thinking of a seventeenth-century woman.”[4]

Leave a comment