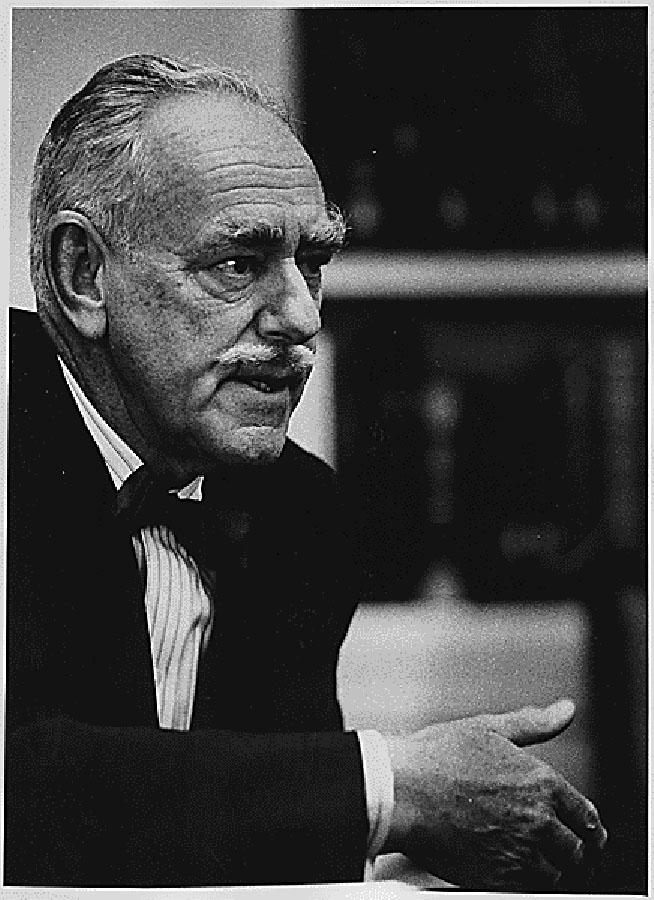

Sir Kenneth Strong, chair of the UK’s Joint Intelligence Board, was in Washington during the early phases of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when he received advance word of the missile deployments and of a U.S. plan for a first strike against the Soviet Union in the event of a confrontation over West Berlin. (Photo from Wikipedia)

I have been waiting for a lull in the action to do a dress down of Pete Hesgeth, and to post on Sir Kenneth Strong, who might have won the Cuba Missile Crisis for the President of the United States, whose nephew is acting like a….HYSTERICAL LUNATIC! Strong may be the man James Bond yearned to be. I will see if Ian Fleming knew him.

It hurts to do what I do. It makes me ill the older I get. I am a newspaperman. I saw Brit Hume suffering the same sickness. It is hard to take, the truth, that sometimes the most incompetent people – rise to the top! If Hitler had not rose to the top, there would be no need for another Israel. Strong was in Germany and saw the monster rise to the power. There a good chance Sir Ian Easton knew Strong.

Here’s what I see, a man who is working on several Bond books. I see Sir Strong, getting out of his chair at that press conference, walking up to Pete – and give him a good slap across the face!

“Buck up – man! You’re hysterical. The enemy is watching. Are you going to do your duty, or, are you going to resign!”

Headbutt Pete would look into those eyes, and know instantly Sit Strong has seen a lot of assholes in his line of work…..which is what? Assess the situation, and make judgements on all the men involved! Hpw about…the woman?

John Presco

Pete Hegseth Slams Former Fox Colleague As The ‘Worst’ During Briefing

By Mandy Taheri

Weekend Reporter

Newsweek Is A Trust Project MemberFOLLOW

news article

17

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, a former Fox & Friends Weekend co-host, publicly criticized his former colleague Jennifer Griffin, calling her “about the worst” during a Thursday morning press briefing, taking issue with her reporting and line of questioning on the administration’s recent strikes against Iran.

His remarks, which also lambasted the media and numerous outlets, have sparked backlash from critics and journalists.

Why It Matters

The exchange comes days after the U.S. struck three Iranian nuclear sites, Isfahan, Fordow and Natanz. The Trump administration has lauded the military mission, in which B-2 stealth bombers used bunker bombs on Fordow, which is deep underground inside a mountain.

Trump has said that the strikes resulted in “total obliteration” of the facility, although the Defense Intelligence Agency’s (DIA) preliminary report suggests damage and not complete destruction. The DIA is part of the Pentagon, which Hegseth oversees.

Hegseth’s rebuke of Griffin comes as members of the Trump administration increasingly use personal attacks in response to dissenting views or media coverage. During the briefing, Hegseth criticized the press for its reporting on the leaked initial damage assessment that cast doubt on the totality of the strikes, echoing sentiments expressed by the president on his social media platform.

What To Know

On Thursday, during the question and answer portion of the briefing, Griffin, Fox News‘ chief national security correspondent, asked Hegseth, “Do you have certainty that all the highly enriched uranium was inside the Fordow mountain, or some of it, because there were satellite photos that showed more than a dozen trucks there two days in advance—are you certain that none of the highly enriched uranium was moved?”

Uranium enrichment increases the concentration of uranium-235, the isotope necessary to sustain a nuclear chain reaction used in both power generation and nuclear weapons. The process is central to weapons development, which the U.S. and Israel accuse Iran of pursuing, though Tehran insists its nuclear program is solely for energy purposes.

The comment comes after the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Rafael Grossi, said, “We do not have information on the whereabouts of this material” in reference to 900 pounds of potentially enriched uranium that Iranian officials said had been removed ahead of the strikes. Grossi said the comments on Fox News The Story with Martha MacCallum on Tuesday.

Read more Pete Hegseth

- Pete Hegseth Trashes Former Fox News Colleague to Her Face During Briefing

- FBI Warns of Possible Iran Retaliation Following Strikes on Nuclear Sites

- Iran Says Nuclear Treaty Being Used to Start Wars Not Prevent Them

- DHS Warns of ‘Heightened Threat’ After US Strikes on Iran

Hegseth responded to Griffin first stating, “of course we are watching ever single aspect,” and then took a jab at the veteran journalist, saying, “Jennifer, you’ve been about the worst. The one who misrepresents the most intentionally.”

Griffin, who appeared shocked, responded by pointing out her reporting on the B-2s and the mission as a whole, adding, “So, I take issue with that.”

Many have called out Hegseth’s response to Griffin and noted her storied journalist background, with another former Fox colleague Brit Hume saying it was an undeserved “attack.” Newsweek reached out to Fox New’s press team for comment via email on Thursday, and they directed Newsweek to Hume’s comments on the matter.

The Cuban Missile Crisis @ 60

Briefing NATO Allies

President Kennedy with his close friend British Ambassador David Ormsby-Gore on October 26, 1961. During a lunch meeting with President Kennedy on 21 October 1962, Ormsby-Gore was the first high-level non-U.S. diplomat to learn of the missile deployments and U.S. plans for a blockade. (Photo from John F. Kennedy Library)

British Ambassador First Outsider to Learn of Kennedy Decision for Blockade

British Told of U.S. Preemptive Nuclear Strike Plan if Soviets Moved Against West Berlin

Belgian Foreign Minister “Preferred U.S. to Inform NATO Allies 24 Hours in Advance”

Published: Oct 21, 2022

Briefing Book #

812

Edited by William Burr

For more information, contact:

202-994-7000 or nsarchiv@gwu.edu

Subjects

Regions

Events

Project

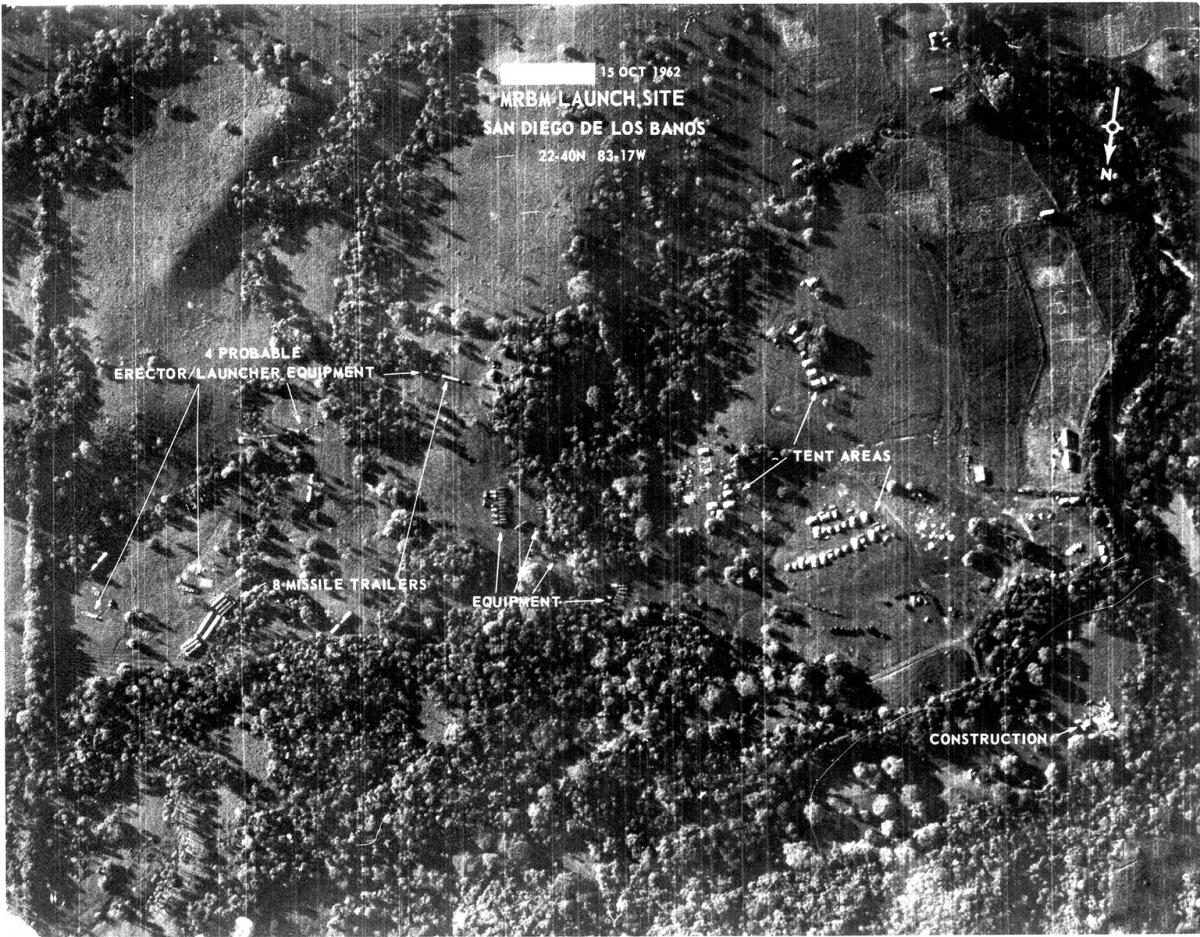

Photograph taken from a U.S. U-2 spy plane on October 15, 1962, of a Soviet missile site in Cuba, subsequently identified as San Cristobal. When CIA briefer Sherman Kent showed photo intelligence to French President Charles De Gaulle, the San Cristobal site was among them.

President Kennedy with British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan at the White House on April 4, 1961. Macmillan received official word from President Kennedy of the missile deployments on the night of October 21, 1962, although British intelligence learned of them a few days earlier. (Photo from John F. Kennedy Library)

Former secretary of state Dean Acheson briefed French President Charles De Gaulle on the Soviet missiles in Cuba during their meeting at Elysée Palace on October 22, 1962. (Photo taken in 1965, from Lyndon B. Johnson President Library).

Sherman Kent, chair of the CIA’s Board of National Estimates, briefed De Gaulle on the Soviet missiles in Cuba on October 22, 1962. (Photo from Wikipedia Commons)

De Gaulle and Kennedy during the latter’s visit to Paris on June 2, 1961. (Photo from John F. Kennedy Library)

West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer meeting with President Kennedy on 12 April 1961. Adenauer received a briefing on the missile deployments on 22 October 1962 (Photo from John F. Kennedy Library)

Sir Kenneth Strong, chair of the UK’s Joint Intelligence Board, was in Washington during the early phases of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when he received advance word of the missile deployments and of a U.S. plan for a first strike against the Soviet Union in the event of a confrontation over West Berlin. (Photo from Wikipedia)

Canadian Prime Minister Diefenbaker with President Kennedy at the White House on 20 February 1961, during a happier moment in their difficult political relationship. Seated: Kennedy; Diefenbaker; Secretary of State for External Affairs of Canada Howard C. Green. Standing (L-R): Secretary of State Dean Rusk; Canada Ambassador to the United States Arnold (A.D.P.) Heeney; United States Ambassador to Canada Livingston T. Merchant, who would brief Diefenbaker on the missile deployments on 22 October 1962. (Photo from John F. Kennedy Library)

Washington, D.C., October 21, 2022 – President John F. Kennedy made unilateral decisions to blockade Cuba and approve other military moves, but winning the support of European allies remained central to U.S. policy during the Cuban Missile Crisis, according to declassified records of briefings prepared for NATO members shortly before Kennedy announced the U.S. discovery of the Soviet missiles.

The first to learn of U.S. plans was British Ambassador David Ormsby-Gore, a close friend of the President’s. According to a declassified telegram found in the British archives, during lunch on October 21, Kennedy told Ormsby-Gore of the missiles and the two choices that he saw: a blockade or an air strike. Asked which option was best, Ormsby-Gore said a blockade, because an air strike would damage the U.S. politically. Kennedy said that was the choice he had made. He told the ambassador that his emphasis was on negotiating the missiles out of Cuba and that he did “not expect or intend that the present course of action” would lead to an invasion of Cuba.

Later that day, Kennedy alerted British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan to the discovery of the missiles and the dangers that he saw, but other NATO allies were not informed until the next day before President Kennedy’s televised speech. Kennedy and his advisers believed that sharing with allies the sensitive photographic intelligence that had informed U.S. decisions, even on short notice, would help win their support. Nevertheless, NATO allies resented the last-minute notification and even more so that they were not consulted about U.S. moves in advance. They supported U.S. actions, but some discontent lay beneath the surface.

Highlights

This compilation consists of the available declassified U.S. records of the briefings given to NATO allies on October 22, 1962, the day of President Kennedy’s first public speech on the crisis. White House reports discuss the briefings of French President Charles De Gaulle, British Prime Minister Macmillan, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, and top NATO representatives. Many of the documents focus on the early communications with the British, the NATO ally with the closest relationship to the United States. One is the record of a lengthy Macmillan-Kennedy telephone conversation the evening of Kennedy’s speech on October 22, 1962. Others concern NATO reactions to U.S. policy, including unease about the late notice. Among the documents are oral histories by former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, who briefed De Gaulle and NATO, and CIA briefer Chester Cooper, who briefed top British officials.[1]

Reports from Cooper and another CIA briefer, Sherman Kent, detail the meetings with De Gaulle and Macmillan, including the latter’s doubts about the U.S. blockade plan. During Cooper’s briefing for British Labour leaders, Hugh Gaitskell said Macmillan felt “hurt” by the lack of consultations. Belgian Foreign Minister Paul-Henry Spaak was “understanding” about why Washington had acted before consulting with allies, but “would frankly have preferred U.S. to inform NATO allies 24 hours in advance of our action,” especially because “nobody could have valid objection” to what the U.S. had done.

During Adenauer’s briefing by the CIA’s R. Jack Smith, he showed his familiarity with the Agency’s use of cover names when he asked: “Are you sure your name is Smith? Perhaps you have two names.”

The briefing of Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker was more difficult than the others. The Diefenbaker-Kennedy relationship was already bad, and the Prime Minister showed an attitude of “skepticism bordering on antagonism.” But the U.S. record of the meeting indicates that, as the briefing proceeded, Diefenbaker took on a “more considered, friendly, and cooperative manner.”

The decision by the U.S. Embassy in London to release intelligence photos of Soviet missile deployments to the British press irritated the White House and led the Embassy to send a telegram explaining that it took the extraordinary step in an effort to win over the skeptical British media.

One British intelligence official who was in Washington when the crisis broke out was Joint Intelligence Bureau director Sir Kenneth Strong, who summarized his experience in a memorandum for Macmillan. From unnamed U.S. officials, Strong learned about the missile deployments in Cuba and a U.S. plan for a preemptive bomber strike against Soviet ICBMs if Moscow moved against West Berlin—a worst-case scenario that Kennedy said would be “the final failure” of decision-makers at the White House and the Kremlin.

Context: Briefing Allies

President Kennedy and his ExComm advisers believed that the importance of the U.S.-West European security relationship meant that U.S. policy had to be carefully calibrated to avoid jeopardizing NATO. The high value attached to alliance unity meant that Kennedy and his advisers agreed early during the crisis that NATO allies had to receive advance notice of the missile deployment and the U.S. decision for a blockade.

A week before Kennedy made his blockade announcement, while the possibility of an air strike was under debate, he declared that the U.S. had to “alert,” even “consult,” NATO allies on whatever decision was made. In general, Kennedy believed that allies such as De Gaulle and Macmillan had a “right to some warning,” implicitly because of the danger of the situation. Secretary of State Dean Rusk thought along the same lines: The allies would be nervous about being exposed to “all these great dangers without … without the slightest consultation, or warning, or preparation.” A few days later, Rusk observed that “an unannounced, unconsulted, quick action on our part” would lead to disunity in NATO that “the Soviets could … capitalize upon very strongly.”[2]

Consultations were mentioned in the early days, but Kennedy ruled them out by observing that the British would “just object to the idea of a military response.” That raised the general problem of consulting with allies during a crisis: Kennedy wanted to avoid the prolonged debates that heightened the risk of leaks to Moscow or that could delay action until after the missiles in Cuba became operational. Yet, as averse as Kennedy was to consultation, he believed that the British had to be told, at least “the night before.”[3]

Kennedy and advisers like Ambassador Charles Bohlen took it for granted that any decisions made would have to be justifiable. The Allies had little interest in Cuba but worried about threats to West Berlin and to European security. Thus, if war broke out, how could the U.S. explain to allies why it had opted for an air strike or an invasion instead of less violent means or negotiations? On October 18, during an ExComm meeting, Kennedy displayed objectivity about the perceptions of others by observing that U.S. allies see Cuba “as a fixation of the United States and not a serious military threat.” They “think that … we’re slightly … demented on [Cuba],” so if the U.S. invaded or launched an air strike, “no matter how good our films are … a lot of people would regard this as a mad act by the United States.”[4]

After Kennedy decided on the blockade and its date, plans for advance warning to NATO allies and others went ahead. On October 21, Under Secretary of State George Ball announced the plan (which was already underway): Ambassador Walter Dowling would meet with Adenauer; Ambassador David K.E. Bruce would speak with Macmillan; and Dean Acheson would brief De Gaulle and the North Atlantic Council (the new U.S. Ambassador to France, Charles E. Bohlen, was in transit, by ocean liner, on the Atlantic). Not mentioned was Diefenbaker, who would also be briefed. “Present at [the] briefings would be technical experts from CIA who could answer questions concerning the photographic intelligence which reveals the missile sites.”

According to the memoirs of CIA briefer Cooper, late in the afternoon of October 20, Acheson, Dowling (who was then in Washington), Cooper, and two other CIA officials—Board of National Estimates chair Sherman Kent and Deputy Director of Current Intelligence R. Jack Smith—gathered at the State Department, where they received instructions on their assignments. Flying on a presidential aircraft, the group left the next morning, arriving at midnight at the British air force base at Greenham Common. Ambassador Bruce (armed with a handgun for security) met the arriving group and drove Cooper to the Embassy in London, while Acheson, Kent, Dowling, and Smith flew on to Paris and to Bonn. To brief the Canadian prime minister, former ambassador Livingston Merchant and CIA officer William Tidwell flew to Ottawa. That Diefenbaker was never mentioned among the names of allies to be informed indicated the marginality of the prime minister, and Canada in general, in policy deliberations during the crisis.[5]

The British would receive the earliest warning, although that was not part of the State Department plan. The next day, on October 21, President Kennedy had a secret lunchtime meeting with his close friend, British Ambassador Ormsby-Gore, to whom he gave a detailed briefing. Later that day, Kennedy wrote to Macmillan about the crisis, but did not tell him about the blockade plan until October 22.

The meeting with heads of state in France, the United Kingdom, and West Germany, along with NATO officials, accomplished their basic purpose. Adenauer, De Gaulle, and Macmillan expressed support for U.S. plans and were fascinated by the photographic intelligence. The briefing to NATO received a generally positive reception. The briefing for Diefenbaker was more difficult because he was initially critical and argumentative. But the Canadian prime minister eventually came around, and the Canadian government proved highly supportive. Cooper’s expedited release of selected photographs, which soon appeared in the British and French media, helped clinch the case before the European public.

Cooper and other official observers quickly discerned underlying dissatisfaction among NATO partners. While the legitimacy of the U.S. response was not challenged, its implications for European security, should the situation escalate, troubled the allies, who believed that they should have been consulted in advance or at least been given earlier notice of U.S. decisions. British Labour leaders told Cooper that Macmillan was upset that Kennedy had not consulted him earlier, although the two would have significant exchanges as the crisis developed. Belgian Foreign Minister Paul-Henri Spaak told the U.S. ambassador that NATO should have been given 24 hours’ notice, while De Gaulle was said to have felt some “pique” about the lack of consultation. An intelligence survey indicated that those concerns were shared in NATO Europe, with “some Italians” being “extremely annoyed.” Kennedy’s decision to negotiate a secret swap of Jupiter missiles in Turkey for Soviet missiles in Cuba might have been controversial in NATO circles if it had become known, but the deal remained secret for years.

NATO allies did not make a fuss about crisis consultations, because that could have strained trans-Atlantic connections and allowed the Soviets to exploit the situation, which Rusk had feared. Thus, European reliance on the U.S. for security gave Washington freedom of action, although Kennedy’s recognition of the importance of allied opinion influenced the choices that he made. Some have argued that Kennedy’s avoidance of consultations in the early stages of the crisis had a “poisonous effect” on U.S.-European relations. If so, the poison did not kill the alliance but may have contributed to its weakening. While De Gaulle was already abandoning his proposal for a formal US-UK-French tripartite system of policy coordination, the Cuban Missile Crisis likely strengthened his determination to chart France’s own course outside of the NATO military structure.[6]

Note: Special thanks to Len Scott, Aberystwyth University, for generously sharing important British archival records. Thanks also to Aline Keledjian, George Washington University, for research assistance.

Leave a comment