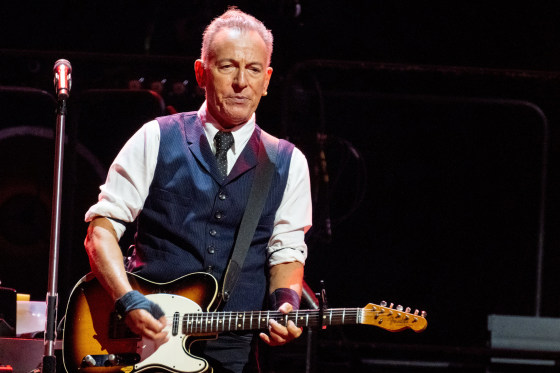

Bruce Springsteen performing in Manchester, England, on Thursday.Shirlaine Forrest / Getty Images

He went to Nazareth, where he had been brought

This statue of US President Abraham Lincoln in Manchester, England commemorates the support of local cotton workers for the Union

San Sebastian Avenue

On the morning of May 16. 2025, I discovered the British Government passed an Abolition Law in 1833 that included the purchase of slaves from their owners. Did you know that?

For the last two days I have been studying Britain’s tole in our Civil War, and am shocked! A victory for the Union was a great threat to the crown and the wealthy Lords who defended it. Consider the truth Trump went on a Royal Tour of leaders – who reject Democracy – while saying the European are the parasitical threat to the U.S.A. How many members of NATO are trye Democracies?

The Supremes Court if hearing the case King Trump is making about who is a Citizen, and who is not Trump rose to power thanks to the Covert Neo-Confederate leaders and their false teachers of a fake Jesus – who came to restore the Jubilee laws – AND PURCHASE FREEDOM FOR SLAVES?

For over ten years I have been puzzled why Jews tried to throw Jesus off a cliff. I am not alone. Why does Lk 4,16-30 reveal Jesus’ Mission – that is absent in the other gospels? It appears Luke is suggesting Paul’s Jesus did not join the Tax Rebellion, the burning of the debt archives that led to the War with Rome om 70 AD.

Jesus wore a purple robe that is associated with the Flavian family that ruled England. For this reason I have wondered if Jesus was a Flavian – as they were in early English History. I have wondered if Jesus was born in England, and considered himself….

THE TRUE KING OF ROMANS

How about….The Emperor of Britain?

To be continued!

The Union victory emboldened the forces in Britain that demanded more democracy and public input into the political system. The resulting Reform Act 1867 enfranchised the urban working class men in England and Wales, thus weakening the upper-class landed gentry, who identified more with the Southern planters. Influential commentators included Walter Bagehot, Thomas Carlyle, John Stuart Mill and Anthony Trollope.[51] Additionally, many British and Irish men saw service in both the Union and Confederate State Army.

| THE JUBILEE YEAR IN THE GOSPEL OF LUKE Albert Vanhoye For the preparation of the Great Jubilee particular importance must surely be given to the passage in the Gospel of Saint Luke which tells us about Jesus’ preaching in Nazareth (Lk 4,16-30). The passage in fact is the only one in the whole of the New Testament which mentions a jubilee year, giving it great importance. Therefore it would seem opportune to offer some reflection on this subject.1. Saint Luke is not the only evangelist who records Jesus’ visit to Nazareth “where he had been brought up” (Lk 4,16). Saint Mark and Saint Matthew also refer to this episode, although without mentioning the name of the town, referred to simply as “his home town” (Mk 6,1; Mt 13,54). There are however several differences between the story told by Luke and those of Mark and Matthew. We have already implicitly indicated one, when we observed that Luke is the only one who gives the contents of Jesus’ preaching. The other two evangelists limit themselves to saying that Jesus “began to teach in the synagogue” (Mk 6,2; |

Bruce Springsteen delivered stinging criticism of the Trump administration at the opening show of his British tour, accusing its officials of authoritarianism, rolling back civil rights and illegal deportations.

Springsteen, 75, a prominent liberal who has long supported Democratic presidential candidates including former Vice President Kamala Harris, made the remarks at a concert in Manchester, England, on Wednesday that was the first in his “Land of Hope and Dreams” tour.

“The mighty E Street Band is here tonight to call upon the righteous power of art, of music, of rock ’n’ roll in dangerous times,” he said to roars from the crowd.

“In my home, the America I love, the America I’ve written about, that has been a beacon of hope and liberty for 250 years, is currently in the hands of a corrupt, incompetent and treasonous administration.”

Springsteen then asked supporters of democracy to “raise your voices against authoritarianism and let freedom ring!” before beginning the show.

In May 1772, Lord Mansfield‘s judgment in the Somerset case emancipated a slave who had been brought to England from Boston in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and thus helped launch the movement to abolish slavery throughout the British Empire.[2][3] The case ruled that slavery had no legal status in England as it had no common law or statutory law basis, and as such someone could not legally be a slave in England.[4] However, many campaigners, including Granville Sharp, took the view that the ratio decidendi of the Somerset case meant that slavery was unsupported by law within England and that no ownership could be exercised on slaves entering English or Scottish soil.[5][6] Ignatius Sancho, who in 1774 became the first known person of African descent to vote in a British general election, wrote a letter in 1778 that opens in praise of Britain for its “freedom, and for the many blessings I enjoy in it”, before criticizing the actions towards his black brethren in parts of the Empire such as the West Indies.[7][8]

United Kingdom and the American Civil War

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland remained officially neutral throughout the American Civil War (1861–1865). It legally recognized the belligerent status of the Confederate States of America (CSA) but never recognized it as a nation and neither signed a treaty with it nor ever exchanged ambassadors. Over 90 percent of Confederate trade with Britain ended, causing a severe shortage of cotton by 1862.[1] Private British blockade runners sent munitions and luxuries to Confederate ports in return for cotton and tobacco.[2] In Manchester, the massive reduction of available American cotton caused an economic disaster referred to as the Lancashire Cotton Famine.[3] Despite the high unemployment, some Manchester cotton workers refused out of principle to process any cotton from America, leading to direct praise from President Lincoln, whose statue in Manchester bears a plaque which quotes his appreciation for the textile workers in “helping abolish slavery”.[4] Top British officials debated offering to mediate in the first 18 months, which the Confederacy wanted but the United States strongly rejected.

Large-scale trade continued between Britain and the US. The US shipped grain to Britain, and Britain sold manufactured items and munitions to the US. British trade with the Confederacy fell over 90% from the prewar period, with a small amount of cotton going to Britain and hundreds of thousands of munitions and luxury goods slipped in by numerous small blockade runners operated and funded by British private interests.[2]

The Confederate strategy for securing independence was based largely on the hope of military intervention by Britain and France. A serious diplomatic dispute erupted over the “Trent Affair” in late 1861 but was resolved peacefully after five weeks.

British intervention was likely only in co-operation with France, which had an imperialistic venture underway in Mexico. By early 1863, intervention was no longer seriously considered, as Britain turned its attention elsewhere, especially toward Russia and Greece.[5] In addition, at the outbreak of the American conflict, for both the United Kingdom and France the costly and controversial Crimean War (October 1853 to February 1856) was in the still-recent past, the United Kingdom had major commitments in British India in the wake of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, and France had major imperial ambitions outside of the Western Hemisphere, and was considering or had already commenced military ventures in Morocco, China, Vietnam, North Africa, and Italy.

A long-term issue was the sales of arms and warships to the Confederacy. Despite vehement protests from the US, Britain did not stop the sales of its arms and its shipyard (John Laird and Sons) from building two warships for the Confederacy, including the CSS Alabama.[6] Known as the Alabama Claims, the controversy was partially resolved peacefully after the Civil War when the US was awarded $15.5 million in arbitration by an international tribunal only for damages caused by the warships.

In the end, British involvement did not significantly affect the outcome of the war.[7] The US diplomatic mission, headed by Minister Charles Francis Adams Sr., proved to be much more successful than the Confederate missions, which were never officially recognized by Britain.[8]

Confederate policies

Main article: Diplomacy of the American Civil War

Confederate opinion, led by President Jefferson Davis, was dominated by “King Cotton,” the idea that British dependence on cotton for its large textile industry would lead to diplomatic recognition and mediation or military intervention. [citation needed]The Confederates had not sent out agents ahead of time to ascertain if the King Cotton policy would be effective.[citation needed] Instead, it was by popular demand, not government action, that shipments of cotton to Europe were ended in spring 1861.[citation needed] When the Confederate diplomats arrived, they tried to convince British leaders that the US naval blockade was an illegal paper blockade.[9] Historian Charles Hubbard writes:

Davis left foreign policy to others in government and, rather than developing an aggressive diplomatic effort, tended to expect events to accomplish diplomatic objectives. The new president was committed to the notion that cotton would secure recognition and legitimacy from the powers of Europe. The men Davis selected as secretary of state and emissaries to Europe were chosen for political and personal reasons – not for their diplomatic potential. This was due, in part, to the belief that cotton could accomplish the Confederate objectives with little help from Confederate diplomats.[10]

Hubbard added that Davis’s policy was stubborn and coercive. The King Cotton strategy was resisted by the Europeans. Secretary of War Judah Benjamin and Secretary of the Treasury Christopher Memminger warned that cotton should be immediately exported to build up foreign credits.[11]

Union policies

Main article: Diplomacy of the American Civil War

The Union’s main goal in foreign affairs was to maintain friendly relations and large-scale trade with the world and to prevent any official recognition of the Confederacy by any country, especially Britain.[citation needed] Other concerns included preventing the Confederacy from buying foreign-made warships; gaining European support for policies against slavery; and attracting immigrant laborers, farmers, and soldiers.[citation needed]There had been continuous improvement in Anglo-American relations throughout the 1850s. [citation needed]The issues of Oregon, Texas and the border between the United States and the British colonies had all been resolved, and trade was brisk. Secretary of State William H. Seward, the primary architect of American foreign policy during the war, intended to maintain the policy principles that had served the country well since the American Revolution: “non-intervention by the United States in the affairs of other countries and resistance to foreign intervention in the affairs of the United States and other countries in this hemisphere.”[12]

British policies

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2025) |

British public opinion was divided on the American Civil War, though historians have noted that most Britons did not express an opinion on the matter.[13][1] The Confederacy tended to have disproportionate support from the Catholic, and Irish, with one national petition of 300,000 signatories in support of secession having almost half its support from the Irish, and Catholic clergy, a demographics that made up less than 25% of the 28.8 million population of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1861: Britain: 23, Ireland: 5.8 million).[14] Similarly it is noted approximately 40,000 Irishmen (0.1% of the population), and 10,000 Englishmen (0.04% of the population) would sign on to serve the Confederacy, while 170,000 Irish (2.9% of the population), and 50,000 British (0.2% of the population) would fight for the Union, a ratio of 4.6:1 in favour of Union service.[15][16] Of the 658 MPs sitting in the Commons in 1861, twenty one (3%) would join the Manchester headquartered, Confederacy supporting, Southern Independence Association, as would ten Lords.[17] Others assert elites: the aristocracy and the landed gentry, which identified with the Southern planter class, and Anglican clergy and some professionals who admired tradition, hierarchy and paternalism. The Union was favored by the middle classes, the religious Nonconformists, intellectuals, reformers and most factory workers, who saw slavery and forced labor as a threat to the status of the working man.[citation needed]

As for the government, Chancellor of the Exchequer William Ewart Gladstone, whose family fortune had been based on slavery in the West Indies before 1833, supported the Confederacy. Foreign Minister Lord Russell wanted neutrality. Prime Minister Lord Palmerston wavered between support for national independence, his opposition to slavery and the strong economic advantages of Britain remaining neutral.[18]

Even before the war started, Lord Palmerston pursued a policy of neutrality. His international concerns were centered in Europe, where he had to watch both Napoleon III‘s ambitions in Europe and Otto von Bismarck‘s rise in Prussia. There were also serious problems involving Italy, Poland, Russia, Denmark and China. British reactions to American events were shaped by past British policies and their own national interests, both strategically and economically.[citation needed] In the Western Hemisphere, as relations with the United States improved, Britain had become cautious about confronting it over issues in Central America. As a naval power, Britain had a long record of insisting that neutral nations abide by its blockades, a perspective that led from the earliest days of the war to de facto support for the Union blockade and frustration in the South.[19]

Diplomatic observers were suspicious of British motives. The Russian Minister in Washington, Eduard de Stoeckl, noted, “The Cabinet of London is watching attentively the internal dissensions of the Union and awaits the result with an impatience which it has difficulty in disguising.” De Stoeckl advised his government that Britain would recognize the Confederacy at its earliest opportunity.[citation needed] Cassius Clay, the United States Minister in Russia, stated, “I saw at a glance where the feeling of England was. They hoped for our ruin! They are jealous of our power. They care neither for the South nor the North. They hate both.”[20]

Lincoln appointed Charles Francis Adams Sr., as minister to Britain. An important part of his mission was to make clear to the British that the war was a strictly internal insurrection and afforded the Confederacy no rights under international law.[citation needed] Any movement by Britain to recognizing the Confederacy officially would be considered an unfriendly act toward the US. Seward’s instructions to Adams included the suggestion that it should be made clear to Britain that a nation with widely scattered possessions, as well as a homeland that included Scotland and Ireland, should be very wary of “set[ting] a dangerous precedent.”[21]

Lord Lyons was appointed as the British minister to the United States in April 1859. An Oxford graduate, he had two decades of diplomatic experience before being given the American post. Lyons, like many British leaders, had reservations about Seward and shared them freely in his correspondence, which was widely circulated within the British government.[22][23] As early as January 7, 1861, well before the Lincoln administration had even assumed office, Lyons wrote to British Foreign Secretary Lord Russell about Seward:

I cannot help fearing that he will be a dangerous foreign minister. His view of the relations between the United States and Britain had always been that they are a good material to make political capital of…. I do not think Mr. Seward would contemplate actually going to war with us, but he would be well disposed to play the old game of seeking popularity here by displaying violence toward us.[24]

Despite his distrust of Seward, throughout 1861, Lyons maintained a “calm and measured” diplomacy that contributed to a peaceful resolution to the Trent crisis.[23]

Slavery and trade with the Confederacy

The Confederate States came into existence after seven of the fifteen slave states seceded because of the election of Republican President Lincoln, whose party committed to the containment of slavery geographically and the weakening of slaveowners‘ political power. Slavery was the cornerstone of the South’s plantation economy, although it was repugnant to the moral sensibilities of most people in Britain, which had abolished slavery in its Empire in 1833. Until the fall of 1862, the immediate end of slavery was not an issue in the war; in fact, some Union states (Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Delaware, and what became West Virginia) allowed slavery. In 1861, Missouri had sought to extradite an escaped slave from Canada to face trial for a murder committed in his flight for which some in Britain falsely believed the punishment was to be burned alive.[25][26][27]

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, announced in preliminary form in September 1862, made ending slavery an objective of the war and caused European intervention on the side of the South to be unpopular. However, some British leaders expected it would cause a large-scale race war that might need foreign intervention.[citation needed] Gladstone opened a cabinet debate over whether Britain should intervene, emphasizing the humanitarian intervention to stop the staggering death toll, risk of a race war, and failure of the Union to achieve decisive military results. Ultimately, the cabinet decided that the American situation was less urgent than the need to contain Russian expansion, so it rejected intervention.[28]

During the Civil War, several British arms companies and financial firms secretly conducted business with Confederate agents in Europe, supplying the Confederacy with badly needed arms and military wares throughout the conflict, in exchange for Southern cotton. Companies like Trenholm, Fraser & Company also provided funding for British shipyards which built blockade runners[29] used for running the Union blockade to import badly needed cotton which textile factories in Britain were heavily dependent on. British companies like Sinclair, Hamilton and Company, S. Isaac, Campbell & Company, London Armoury Company and others were the primary suppliers of arms and military supplies, frequently extending credit to Confederate agents for them to make such purchases.[30][31][32] One historian estimated that these actions extended the Civil War by two years and cost 400,000 more lives of Union and Confederate soldiers and civilians.[33]

Trent Affair

Main article: Trent Affair

Outright war was a possibility in late 1861, when the U.S. Navy took control of a British mail ship and seized two Confederate diplomats. Confederate President Jefferson Davis had named James M. Mason and John Slidell as commissioners to represent Confederate interests in England and France. They went to Havana, in Spanish Cuba, where they took passage for England on the British mail steamer RMS Trent.[34] The American warship USS San Jacinto under Captain Charles Wilkes was looking for them.

It was generally then agreed that a nation at war had the right to stop and search a neutral merchant ship if it suspected that ship of carrying the enemy’s dispatches. Mason and Slidell, Wilkes reasoned, were in effect Confederate dispatches and so he had the right to remove them. On November 8, 1861, he fired twice across the bow of the Trent, sent a boat’s crew aboard, seized the Confederate commissioners, and bore them off in triumph to the US, where they were held prisoner in Boston. Wilkes was hailed as a national hero.

The violation of British neutral rights triggered an uproar in Britain. Britain sent 11,000 troops to Canada, and the British fleet was put on a war footing with plans to blockade New York City if war broke out. In addition, the British put an embargo on the export of saltpetre which the US needed to make gunpowder. Approximately 90% of the world’s natural reserves of saltpetre were in British territory and the US had a purchasing commission in London buying up every ounce it could get.[35] A sharp note was dispatched to Washington to demand the return of the prisoners as an apology. Lincoln, concerned about Britain entering the war, ignored anti-British sentiment, issued what the British interpreted as an apology without actually apologizing, and ordered the prisoners to be released.[34]

War was unlikely in any event, as not only was the United States importing saltpetre from Britain, it was also providing Britain with over 40% of its wheat imports during the war years, and suspension would have caused severe disruption to its food supply. Britain imported about 25–30% of its grain (“corn” in British English), and poor crops in 1861 and 1862 in France made Britain even more dependent on shiploads from New York City. Furthermore, British banks and financial institutions in the City of London had financed many projects such as railways in the US. There were fears that war would result in enormous financial losses as investments were lost and loans defaulted on.[36]

Britain’s shortage of cotton was partially made up by imports from India and Egypt by 1863.[37] The Trent Affair led to the Lyons-Seward Treaty of 1862, an agreement to clamp down hard on the Atlantic slave trade by using the US Navy and the Royal Navy.

Possibility of recognizing Confederacy

The possibility of recognizing the Confederacy came to the fore late in the summer of 1862. At that time, as far as any European could see, the war seemed to be a stalemate. The US attempt to capture the Confederate capital had failed, and in the east and west alike, the Confederates were on the offensive. Charles Francis Adams Sr., warned Washington that the British government might very soon offer to mediate the difficulty between North and South, which would be a polite but effective way of intimating that in the opinion of Britain, the fight had gone on long enough and should be ended by giving the South what it wanted. Recognition, as Adams warned, risked all-out war with the United States. War would involve an invasion of Canada, a full-scale American attack on British shipping interests worldwide, an end to American grain shipments that were providing a large part of the British food supply, and an end to British sales of machinery and supplies to the US.[38] The British leadership, however, thought that if the Union armies were decisively defeated, the US might soften its position and accept mediation.[39]

Earl Russell, British Foreign Secretary, had given Mason no encouragement, but after news of the Second Battle of Bull Run reached London in early September, Palmerston agreed that in late September, there could be a cabinet meeting at which Palmerston and Russell would ask approval of the mediation proposal. Then, Russell and Palmerston decided not to bring the plan before the cabinet until they got further word about Lee’s invasion of the North. If the Northerners were beaten, the proposal would go through; if Lee failed, it might be well to wait a little longer before taking any action.[40]

The British working-class population, most notably the British cotton workers who suffered the Lancashire Cotton Famine, remained consistently opposed to the Confederacy. A resolution of support was passed by the inhabitants of Manchester and sent to Lincoln. His letter of reply has become famous:

I know and deeply deplore the sufferings which the working people of Manchester and in all Europe are called to endure in this crisis. It has been often and studiously represented that the attempt to overthrow this Government which was built on the foundation of human rights, and to substitute for it one which should rest exclusively on the basis of slavery, was likely to obtain the favor of Europe.

Through the action of disloyal citizens, the working people of Europe have been subjected to a severe trial for the purpose of forcing their sanction to that attempt. Under the circumstances I cannot but regard your decisive utterances on the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country. It is indeed an energetic and re-inspiring assurance of the inherent truth and of the ultimate and universal triumph of justice, humanity and freedom.

I hail this interchange of sentiments, therefore, as an augury that, whatever else may happen, whatever misfortune may befall your country or my own, the peace and friendship which now exists between the two nations will be, as it shall be my desire to make them, perpetual.

— Abraham Lincoln, 19 January 1863

There is now a statue of Lincoln in Manchester, with an extract from his letter carved on the plinth.

Lincoln became a hero amongst the British working class with progressive views. His portrait, often alongside that of Garibaldi, adorned many parlour walls. One can still be seen in the boyhood home of David Lloyd George, now part of the Lloyd George Museum.

The decisive factor, in the fall of 1862 and increasingly thereafter was the Battle of Antietam and what grew out of it. Lee’s invasion was a failure at Antietam, and he barely escaped back to Virginia. It was now obvious that no final, conclusive Confederate triumph could be anticipated. The swift recession of the high Confederate tide was as visible in Britain as in America, and in the end, Palmerston and Russell dropped any notion of bringing a mediation-recognition program before the cabinet.

Emancipation Proclamation

During the late spring and early summer of 1862, Lincoln had come to see that he must broaden the base of the war. The Union itself was not enough; the undying vitality and drive of Northern anti-slavery men must be brought into full, vigorous support of the war effort and so the United States chose to declare itself officially against slavery. The Lincoln administration believed that slavery was the basis of the Confederate economy and leadership class, and that victory required its destruction. Lincoln had drafted a plan and waited for a battlefield victory to announce it. The Battle of Antietam gave Lincoln victory, and on September 22, he gave the Confederacy 100 days’ notice to return to the Union or else on January 1, 1863, all slaves held in areas in rebellion would be free.[28] William Ewart Gladstone, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and a senior Liberal leader, had accepted slavery in his youth; his family had grown wealthy through the ownership of slaves in the West Indies. However, the idea of slavery was abhorrent to him, and his idea was to civilise all nations.[41] He strongly spoke out for Confederate independence. When the Emancipation Proclamation was announced, he tried to make the counterargument that an independent Confederacy would do a better job of freeing the slaves than an invading northern army would. He warned that a race war was imminent and would justify British intervention.[42] Emancipation also alarmed the British Foreign Secretary Lord John Russell, who expected a bloody slave uprising. The question then would be British intervention on humanitarian grounds. However, there was no slave uprising and no race war. The advice of the war minister against going to war with United States, as well as the tide of British public opinion, convinced the cabinet to take no action.[43]

Confederate diplomacy

Further information: Cotton diplomacy

Once the war with the US began, the best hope for the survival of the Confederacy was military intervention by Britain and France. The US realized that as well and made it clear that recognition of the Confederacy meant war and the end of food shipments into Britain. The Confederates who had believed in “King Cotton” (Britain had to support the Confederacy to obtain cotton for its industries) were proven wrong. Britain, in fact, had ample stores of cotton in 1861 and depended much more on grain from the US.[44]

During its existence, the Confederate government sent repeated delegations to Europe; historians do not give them high marks for diplomatic skills. James M. Mason was sent to London as Confederate minister to Queen Victoria, and John Slidell was sent to Paris as minister to Napoleon III. Both were able to obtain private meetings with high British and French officials, but they failed to secure official recognition for the Confederacy. Britain and the US were at sword’s point during the Trent Affair in late 1861. Mason and Slidell had been seized from a British ship by an American warship. Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, helped calm the situation, and Lincoln released Mason and Slidell and so the episode was no help to the Confederacy.[45]

Throughout the early years of the war, British foreign secretary Lord Russell, Napoleon III, and, to a lesser extent, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, explored the risks and advantages of recognition of the Confederacy or at least offering a mediation. Recognition meant certain war with the US, loss of American grain, loss of exports, loss of investments in American securities, potential invasion of Canada and other North American colonies, higher taxes, and a threat to the British merchant marine with little to gain in return. Many party leaders and the general public wanted no war with such high costs and meager benefits. Recognition was considered following the Second Battle of Manassas, when the British government was preparing to mediate in the conflict, but the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, combined with internal opposition, caused the government to back away.[46]

In 1863, the Confederacy expelled all foreign consuls (all of them British or French diplomats) for advising their subjects to refuse to serve in combat against the US.[47]

Throughout the war, all European powers adopted a policy of neutrality, meeting informally with Confederate diplomats but withholding diplomatic recognition. None ever sent an ambassador or official delegation to Richmond. However, they applied principles of international law and recognized both sides as belligerents. Canada allowed both Confederate and Union agents to work openly within its borders.[48]

Postwar adjustments and Alabama claims

Northerners were outraged at British tolerance of non-neutral acts, especially the building of warships and blockade runners smuggling weapons to the South. The United States at first only demanded vast reparations for “direct damages” caused by British-built commerce raiders, especially CSS Alabama. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the chairman of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, also demanded that “indirect damages” be included, specifically the British blockade runners.[49]

However, Palmerston bluntly refused to pay, and the dispute continued for years after the war. After Palmerston’s death, Prime Minister Gladstone agreed to include the US war claims in treaty discussions on other pending issues, such as fishing rights and border disputes. In 1872, pursuant to the resultant Treaty of Washington, an international arbitration board awarded $15,500,000 to the US only for “direct damages” caused by British-built Confederate ships, and the British apologized for the destruction but admitted no guilt.[50]

Long-term impact

The Union victory emboldened the forces in Britain that demanded more democracy and public input into the political system. The resulting Reform Act 1867 enfranchised the urban working class men in England and Wales, thus weakening the upper-class landed gentry, who identified more with the Southern planters. Influential commentators included Walter Bagehot, Thomas Carlyle, John Stuart Mill and Anthony Trollope.[51] Additionally, many British and Irish men saw service in both the Union and Confederate State Army.

Debt Forgiveness

Posted on November 14, 2012 by Royal Rosamond Press

I posted the following five years ago.

Jon

Jesus has been called `The Wind’ and it was a devastating wind that

struck New Orleans and exposed for the whole world to see how poorly

the evangelico right-wing Christian Republican party have been

treating the needy and the destitute in America. They have been

taking from the poor, and giving unto the rich, using Biblical

teaching, assuring us it is God’s plan to create a trickle-down

economy where the very rich are catered to and given unlimited power

and wealth so they can produce capitol for our Capitalist system

they promise to change into an ecclesiastical state and Kingdom of

God. However, within the very Laws of God, given to Moses in the

Mosaic Laws, already established that Kingdom and bid it be

sustained by the Sabbatical and Jubilee Year to ensure that “the

meek shall inherit the earth” verses the pyramid system that held

the Jews as slaves for many generations, until God gave them LIBERTY.

It is this Liberty that is at the core of the Jubilee where the

Shofar, the horn of the Ram is blown on the Day of Atonement. And

the curtain of the Tabernacle was opened from the top to the bottom,

and come forth the priests carrying the Ark of the Covenant. And

atop the Ark sat The Lord as if upon His thrown. And the trumpets

sounded, and the priests called loudly to the multitude;

“Prepare a way for thy Lord. Make straight paths for him”

I invited all good souls from all nations, who wish to see the

Jubilee Year restored, and thus the Kingdom of God here on Earth –

and never in heaven – to come forth and help prepare the way for the

least amongst you, the poor, the disenfranchised, the disabled, the

blind, all those who have been bruised by the yoke of slavery. It is

time all the poor in America be forgivin of their debts. If the rich

can be forgiven of paying their taxes, by those who claim they are

of God, then anything is possbile.

I have been bid to reveal the core of my book I have been authoring

for many years as there is no time to waste. I will show you how

Paul of Tarsus was bid to created a false teaching to counter this

Jubilee that Jesus brought becacua it was a great threat to Rome,

the great slave-state in the history of humankind. I will show you

how Gentiles were playing a huge role in God’s own revolution that

was sweeping into Europe, and was poised to turn the Roman world

upside down.

Let the Christians in the Red States make atonement for the sin of

slavery, and rid themselves of the false priests who used God’s

words, and Jesus’s teaching to justify slavery. Surley they came

upon the Jubilee Year, and the sound of Jesus blowing the Shofar in

their ear, but, they chose to ignore that Judgement Day. How dare

they force their own upon us, and this Democracy!

I will show you that Jesus was the author of Revelations that are

composed of, and are a continuation of the visions of Ezekiel,

Haggai, and Zechariah, and are the only valid End Times. I declare

the End Time visions of Margaret McDonald, John Darby, and the

Plymouth Brethren, a false revelation.

Throw Jesus Down the Cliff Again?

Jesus Returns Again to Nazareth.

But They Don’t Try to Throw Him Off the Cliff.

So, What’s Different This Time?

What’s the deal?

In the summer of AD 27, Jesus had gone to visit Capernaum after a wedding in Cana. Deciding to change his residence to the house of Peter’s mother-in-law in Capernaum, he stopped at his childhood home in Nazareth during an evangelistic tour of Galilee. While there, he preached in the synagogue where the people attending took offense at him. They had heard of the healings Jesus had been doing, and it seems that they wanted Jesus to stay in the Nazareth area to become their local country doctor. But Jesus was moving on, and some roughnecks in the synagogue tried to throw Jesus down the cliff. Jesus just walked away from them (Luke 4:16-30).

So, he actually went there again?

Yes. Much later, in the late autumn of AD 28, Jesus returned to Nazareth on another evangelical tour. His preaching was scoffed at again, and doubts reigned about his healing powers, but no one tried to toss Jesus down the cliff this time. There was no sign of the angry ruffians from his first visit. What changed? (Mark 6:1-6a.)

Was someone there to protect Jesus?

It looks like that may be the case, and there are some clues in the Bible verses that support that idea. In Luke’s story of the first visit, Jesus arrives in Nazareth apparently alone, and “in the power of the Spirit” fresh from his baptism and 40 days in the desert (Luke 4:14).

For the second visit, Mark is explicit in saying that his disciples were “with him” (Mark 6:1). And the listeners who were astonished by his preaching said, “Aren’t his sisters here with us?” (Mark 6:3b). I would suggest that the ruffians in the synagogue would be less likely to cause a ruckus, for I cannot see a circumstance where Jesus’ disciples would simply let their teacher be thrown down the cliff. And with his sisters there as witnesses, perhaps they may have been shamed into refraining from inciting violence.

And where were Jesus’ four brothers?

It seems that four able-bodied construction workers (“carpenters”) would be a strong deterrent against violence. Even if none of Jesus’ brothers (all older than he) yet believed in him, if they allowed their younger brother to be bullied, they would lose honor in the town and be seen as pantywaists.

I propose that Jesus’ brothers (from Joseph’s first marriage) were absent from Nazareth during Jesus’ first visit, perhaps gainfully employed in the active construction work under way in the nearby Roman city of Sepphoris. And then at his second visit, it is probable from Mark’s text that Jesus’ brothers were in town, or at least nearby.

In the company of Jesus’ disciples, his brothers, and yes, even his sisters, there was plenty of motivation for the town ruffians to refrain from messing with Jesus.

Why Did Jesus Heal Few in Nazareth?

Mark 6:5 relates, “He could do no miracles there, except that He laid His hands on a few sick people and healed them” (Mark 6:5 NASB). This verse has troubled theologians for centuries. Jesus didn’t have the power to heal them?

The answer lies in Jesus’ healing practices. In most every case, Jesus healed those who came to him asking for healing. (One exception was at Bethesda, where he asked, “Do you want to be healed?”) But in Nazareth there was little belief or confidence, and even less respect for his ministry.

Jesus could not heal many there because few came forward to be healed. Simple.

Leave a comment