“In 1849 the plains were crossed with ox-teams, on the route via Salt Lake City; and the journey was brought to an end at Frémont, California, a place at the junction of the Feather and Sacramento rivers”

San Sebastuab Avnue

For many years I have been looking for any trace John Fremont founded a State Capitol in California Eureka! I found it – in the history Judge Joshua Walton, whose memory was dug up in the middle of the night – and cast out of the University that no doubt used the Walton-Skinner family to show parents the University of Oregon – WAS STEEPED IN THE TRADITION OF THE PIONEER FAMILIES!

When did the UofO first receive Government Grants? I am going to file a claim for the 100,000 acres the Feds gave to found the UofO. Did the Walton-Skinner family donate money – and land – believing they would be honored – forever

I am also going to file a lawsuit for 70 acres that the Fremont’s owned at Fort Mason. I suspect the Mason family became concerned when it was rumored Prussia wanted to purchase California. The Mason’s descend from Signer George Mason, and may be the most powerful family in America. How about, the world? I have long suspected Fremont and his wife were plagued by assassins – who might have been…..

CAVALIERS

I believe I found the hidden reason for the Revolutionary war – and the Civil War?

John Presco

President: Royal Rosamond Press

Mason’s great-grandfather George Mason I was a Cavalier who was born in 1629 in Pershore, Worcestershire, England. Militarily defeated in the English Civil War, Mason and other Cavaliers emigrated to the American colonies in the 1640s and 1650s.[6]

In 1841, John C. Fremont (28 years old) marries Jesse Benton, daughter of the powerful Missouri Senator Charles Benton

Partially due to Fremont’s ignorance with military rank and procedure, he found himself at odds with Col. Richard B. Mason when Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny appointed Mason the Governor of California, a position which Fremont held after being appointed earlier by Commodore Stockton. Furious with his impending removal as governor, Fremont challenged Mason to a duel, but after the duel was postponed General Kearny had Fremont arrested and sent to Fort Leavenworth where he was court-martialed and charged with disobedience toward a superior officer and military misconduct.

The University of Oregon first received federal land grants in 1859 when Oregon became a state. Congress granted Oregon 100,000 acres for the establishment and support of a state university. This led to the University of Oregon’s establishment in 1872, with instruction beginning in 1876.

October 12, 1872: The University of Oregon was established by an act of the Oregon State Legislature despite funding concerns. Area residents struggled to help finance the institution, holding numerous fundraising events such as strawberry festivals, church socials, and produce sales. Lane County citizens raised an astounding $27,500 to buy seventeen acres of land and build Deady Hall. Since then, the donation

Map of Oregon and Upper California from the Surveys of John Charles Freemont and Other Authorities

Biography of Judge Joshua J. Walton

JUDGE JOSHUA J. WALTON. – This eminent jurist and public leader of our state was born April 6, 1838, at Rushville, Illinois. At the age of two years he was taken by his parents to a new home near Springfield, Illinois. After a brief sojourn there another move was made, bringing the family as far west as St. Louis, Missouri; and in 1842 they moved on to Keosauque, Iowa. In 1849 the plains were crossed with ox-teams, on the route via Salt Lake City; and the journey was brought to an end at Frémont, California, a place at the junction of the Feather and Sacramento rivers. Two years later the line of march was resumed; and Yreka was made the objective. The next year a more permanent location was found in the Rogue river valley; and a Donation claim was taken on Wagner creek on the beautiful farm now known as the Beason place. That was at a time when the Rogue river Indians were very troublesome, and quite generally on the warpath. The elder Walton engaged to some extent in mining at Jacksonville and Rich Gulch; and young Joshua, then but a lad of fourteen, also essayed to make his pile by rocking a “Long Tom.” With his father he also used to go on freighting expeditions to procure goods from the Willamette valley for the market at Jacksonville, Yreka, or the mining camps on the Klamath; and his work was to ride the bell animal. While thus occupied he carried his school books, and spent the slow hours in the saddle acquiring the rudiments of an education.

Upon the outbreak of the Indian war in 1853, the family went to the fort at Jacob Wagner’s, and remained until the autumn. By the various scares and indeed great perils of the time, Mrs. Walton had acquired a constant dread of the savages, and, in order to giver her less anxiety, Mr. Walton decided to seek a new location, less isolated and less exposed, and consequently sold his right to Mr. Beason, and made the same year a new home in the Umpqua valley, a few miles west of Oakland, in a little oasis known as Green valley. Among other benefits derived from this change was the advantage of a good school then just started, at which Joshua made rapid progress in his books under the tutelage of Professor J.S. Gilbert, a worthy man and an excellent teacher.

In the fall of 1858 a final removal was made to Eugene City, Oregon. At that beautiful place a permanent home was located; and there Judge Walton resides at the present time. With the exception of a short time spent in the Idaho mines, he has resided there continuously. At that center, which even in the early days boasted much culture and ability, young Walton found opportunities not hitherto enjoyed for the development of his mind, and soon began the study of law under Honorable Riley E. Stratton, then circuit judge of the second judicial district. He also read somewhat with Honorable Stukeley Ellsworth. He was admitted to the bar in 1863, at the September term of the supreme court, in the first class ever examined by that court in open session. The class was large, including in the number some whose names have since become eminent, as C.B. Bellinger, Joseph F. Watson, P.S. Knight and other men of mark.

Soon after completing his studies, Mr. Walton was called upon to occupy public positions, and has spent the greater part of his life in official or other public duties. In 1866 he was elected county judge of Lane county. In 1876 he was appointed to the same position by Governor L.F. Grover, to fill the place made vacant by the resignation of Judge John M. Thompson. In the same year his position was confirmed by election; and he served out a full term. In 1874 he was elected president of the Union University Association, and successfully superintended the erection of the university building at Eugene, and also succeeded in securing the location of the State University at that city. In 1880 he received the nomination for circuit judge of the second judicial district; but the contest resulted in the election of his opponent on the Republican ticket, Honorable Joseph F. Watson.

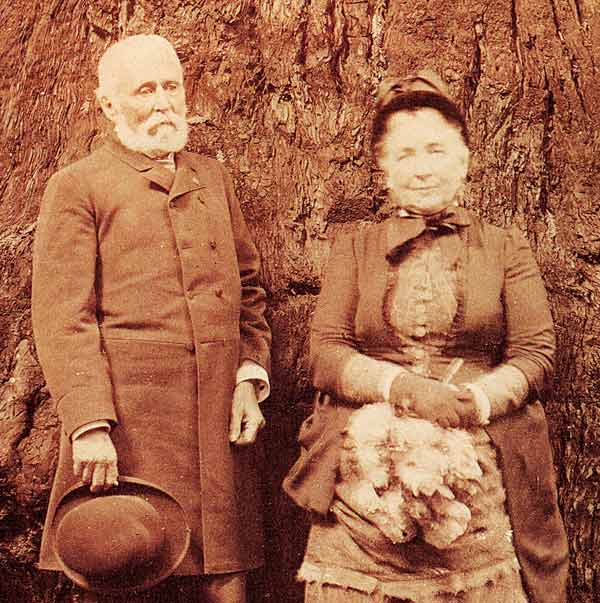

Judge Walton has been twice married, first to Miss Lizzie Gale, who died in 1873, and secondly, in 1876, to Miss Emma Fisher.

Fremont Landing, California

| Fremont Landing | |

|---|---|

| Former settlement | |

Coordinates:  38°46′58″N 121°37′08″W 38°46′58″N 121°37′08″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Yolo County |

| Elevation[1] | 26 ft (8 m) |

Fremont Landing (also known as Fremont and Fremonts[2]) was a former settlement in Yolo County, California, United States. It was located on the Sacramento River 5.5 miles (8.9 km) east-southeast of Knights Landing,[2] at an elevation of 26 feet (8 m).[3]

History

The area was settled by Jonas Spect on March 22, 1849, one half of a mile below the merging of the Feather River into the Sacramento River.[2][4] Lt. George H. Derby wrote about the town on his report to the Secretary of War in 1849 and stated, “The Town of Vernon is situated at the junction of the Feather and Sacramento Rivers, and that of Fremont immediately opposite. Each contains some twenty houses and one or two hundred inhabitants.”[4]

Spect chose to settle at this site because of the potential business benefits of being upriver. Mexican law entitled people to a three league town if they would start a ferry service, which Spect then began. He hired John I. McCaughn to survey his three league town soon after he started his ferry business. The town was named after John C. Frémont, who had risen to public notoriety only three years beforehand. During the Municipal Election of October 1, 1849, there were around 300 voters in the area.[4]

On April 5, 1850, the town received its first post office, the Fremont Post Office, and the title of county seat.[4] Severe floods during the previous winters foreshadowed the fall of the city. These floods allowed for travel upriver and led to the founding of Marysville, closer to the mines. A legal battle for land rights between Spect and James Madison Harbin didn’t help assuage fears of the townspeople. In 1851 the town of Fremonts Landing was disbanded; people moved out and took the town’s buildings with them. Washington became the county seat on June 30, 1851. Very few citizens stayed in the area, with only three voters in the September 1855 general election. The post office was also closed, then opened again in the same year. The post office closed its doors permanently in November 1864. In 1870 the town had one house left.[4]

References

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Fremont Landing, California

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Durham, David L. (1998). California’s Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, California: Word Dancer Press. p. 488. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- ^ “GNIS – Fremont Landing”. USGS. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Three Maps of Yolo County. Woodland, CA: Yolo County Historical Society. 1970. p. 1.

External links

Retrieved from “https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fremont_Landing,_California&oldid=1180726592“Last edited 2 years ago by Funster78

Languages

Drawn By: Charles Preuss Litho By: E. Weber & Co.

Date: 1848 (dated) Baltimore

Dimensions: 33.25 x 26.5 inches (84.5 x 67.3 cm)

Increasingly rare and important map of Upper California and the Oregon Territory drawn from the expeditions of John C. Fremont, Christopher “Kit” Carson, and Charles Preuss to the American Western Frontier. This landmark map has historical importance for a number of reasons, but none more than its support for the prevailing 19th century idea of Manifest Destiny and the cartographic documentation of Freemont’s three expeditions.

In 1841, John C. Fremont (28 years old) marries Jesse Benton, daughter of the powerful Missouri Senator Charles Benton whom championed the expansionist movement, a political cause that became known as Manifest Destiny. Through his political power and influence, Benton procured funding and patronage for his new son-in-law John Fremont to lead three separate expeditions into the Oregon Territory, Great Basin, Sierra Nevada Range, and several parts unknown in what was then Upper California. Fremont’s first expedition of 1842 ultimately created the official path of the Oregon Trail and lead him to meet the legendary trapper and scout Kit Caron who would guide much of the three expeditions to which Fremont is given credit.

Fremont’s 2nd Expedition (1843-44)

Fremont set out with the intention to find an alternate route to Oregon and the Pacific through what is now Colorado. Unable to traverse the Colorado Rockies, the expedition continued along their first route through South Pass, (which was already crowded with emigrants on the Oregon Trail) to the Great Salt Lake where he discovered the previously unknown Mormon settlement, which is noted on the map. The expedition continued northwest to Fort Hall and Fort Boise then along the Snake and Columbia River deep into Oregon country, coming within sight of the Cascade Range and mapping Mount St. Helens and Mount Hood. After a “quick” stop to the British-held Fort Vancouver for supplies, the party turned south to further explore the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the Great Basin of present-day Utah. Fremont was the first American to see Lake Tahoe and accurately determined that the Great Basin was endoheric which means a land that is absent of any rivers that flow to an ocean.

Fremont’s 3rd Expedition (1845)

Again, Fremont with the guidance of Kit Carson and cartographic skillset of Charles Preuss set out for the west. This expedition however was partly as a scientific expedition, but also as a military operation under the request of then-president James H. Polk who was willingly trying to bring about a war with Mexico in an effort to conquer new territory and connect the eastern half of the country with California. During this expedition, Fremont split his party into two in an effort to cover more ground and ultimately played a role in taking control of California for Mexico. During this expedition, Fremont named the Golden Gate entrance to San Francisco Bay, and made his way through the old Spanish forts and towns of Monterey, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and San Diego.

Court-martial of John C. Fremont

Partially due to Fremont’s ignorance with military rank and procedure, he found himself at odds with Col. Richard B. Mason when Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny appointed Mason the Governor of California, a position which Fremont held after being appointed earlier by Commodore Stockton. Furious with his impending removal as governor, Fremont challenged Mason to a duel, but after the duel was postponed General Kearny had Fremont arrested and sent to Fort Leavenworth where he was court-martialed and charged with disobedience toward a superior officer and military misconduct.

Having been court-marshaled and dismissed from the Army in 1847, Fremont was asked to not publish the details of this last expedition by the Corps of Topographical Engineers as would normally be required. Instead, a geographical memoir comprised his report. It was published nonetheless by Congress at the behest of the powerful Senator Thomas Hart Benton, Fremont’s father-in-law. The memoir with which this map appeared is also known as Misc. Doc. No. 148, 30th Congress, 1st Session. Fremont would later make two more expeditions in the west, however these were regarded as far less successful and are deemed of less historical importance than the first three.

Important Cartographic Aspects of Fremont’s Map

This map is loaded with detail that only becomes more intriguing as one looks closer. Numerous native American tribes are noted throughout including the Navahoes, Apaches, Pah-Utah, Yumas, Shoshones, Nez-Perce, Umpqua, Chinooks, Wallah-Wallah, and Flatheads to name a few. As mentioned earlier, important early towns, forts, and geographical regions are also named, including “Mormon Settlements” near Great Salt Lake, “El Dorado of Gold Region” near the American River, “Golden Gate,” Pyramid Lake, Puebla de Los Angeles, S. Diego, S. Barbara, Monterey, Fort Hall, Fort Boise, South Pass, etc.

As much as this map was an early cartographic breakthrough in the mapping of the west, there is still a lot that was left unknown. One obvious example of this is a vast are in the Great Basin that is simply labeled “Unexplored.” Additionally, there is an exaggerated or false mountain range running east-west that is labeled “Dividing Range Between the Waters of the Pacific and the Waters of the Great Basin.” The map notes just beneath this range that “These mountains are not explored, being only seen from elevate points on the northern exploring line.”

Condition: This spectacular map is in A condition with bold original outline color on clean paper that has been lightly toned with age. The map has been flattened and linen-backed for preservation and presentation purposes.

Inventory #11917

1200 W. 35th Street #425 Chicago, IL 60609 | P: (312) 496 – 3622

Richard Barnes Mason, born in Fairfax County, Virginia, January 16, 1797, was the son of George Mason and Elizabeth Mary Ann Barnes Hooe, who were married April 22, 1784.”[6] His grandfather was famous founder George Mason. Richard Barnes Mason inherited a considerable estate, consisting mostly of land and enslaved men and women. Upon the death of his father, he and his siblings frequently squabbled over the division of the estate and the profits made by selling enslaved men and women. In 1823, Richard complained to his brother George that “I wish you would make some exertion to pay me for Tom Clarke [an enslaved man whom the family sold]. It is now six years since you sold him, and I have not yet received a cent. It is not right that, you should, who inherited half my father’s fortune, withhold from me, who got none, what is so justly my due.” Like so many other enslavers and prominent Virginians, Mason’s wealth was heavily dependent upon the labor and bodies of the people he held as slaves.

Mason’s great-grandfather George Mason I was a Cavalier who was born in 1629 in Pershore, Worcestershire, England. Militarily defeated in the English Civil War, Mason and other Cavaliers emigrated to the American colonies in the 1640s and 1650s.[6]

George Mason (December 11, 1725 [O.S. November 30, 1725] – October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, where he was one of three delegates who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including substantial portions of the Fairfax Resolves of 1774, the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, and his Objections to this Constitution of Government (1787) opposing ratification, have exercised a significant influence on American political thought and events. The Virginia Declaration of Rights, which Mason principally authored, served as a basis for the United States Bill of Rights, of which he has been deemed a father.

Little is known of Mason’s political views prior to the 1760s, when he came to oppose British colonial policies.[29] In 1758, Mason successfully ran for the House of Burgesses when George William Fairfax, holder of one of Fairfax County’s two seats, chose not to seek reelection.[30] Also elected were Mason’s brother Thomson for Stafford County, George Washington for Frederick County, where he was stationed as commander of Virginia’s militia during the French and Indian War, and Richard Henry Lee, who worked closely with Mason through their careers.[31]

Revolutionary War

[edit]

In May 1774, Mason was in Williamsburg on real estate business. Word had just arrived of the passage of the Intolerable Acts, as Americans dubbed the legislative response to the Boston Tea Party, and a group of lawmakers including Lee, Henry, and Jefferson asked Mason to join them in formulating a course of action. The Burgesses passed a resolution for a day of fasting and prayer to obtain divine intervention against “destruction of our Civil Rights”, but the governor, Lord Dunmore, dissolved the legislature rather than accept it. Mason may have helped write the resolution and likely joined the members after the dissolution when they met at Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg.[39][40]

Views on slavery

[edit]

Mason routinely spoke out against slavery, even before America’s independence. In 1773, he wrote that slavery was “that slow Poison, which is daily contaminating the Minds & Morals of our People. Every Gentlemen here is born a petty Tyrant.” In 1774, he advocated ending the international slave trade.[142]

Like nearly all Virginia land owners at the time, Mason owned many slaves. In Fairfax County, only George Washington owned more, and Mason is not known to have freed any, even in his March 1773 will[143] ultimately transcribed into the Fairfax County probate records in October 1792 (the original was then lost). That will divided his slaves among his children (between twenty and three years old when Mason wrote it). Mason would continue trading in land as well as remarry (with a marriage agreement recorded in Prince William County in April 1780),[144] and Virginia legalized manumission in May 1782.[145] The childless Washington, in his will executed shortly before his death, ordered his slaves be freed after his wife’s death, and Jefferson manumitted a few slaves, mostly of the Hemings family, including his own children by Sally Hemings.[146] According to Broadwater, “In all likelihood, Mason believed, or convinced himself, that he had no options. Mason would have done nothing that might have compromised the financial futures of his nine children.”[147] Peter Wallenstein, in his article about how writers have interpreted Mason, argued that he could have freed some slaves without harming his children’s future, if he had wanted to.[148]

Black Point

[edit]

Black Point, a promontory point of the San Francisco coastline, is situated on the far point of the headland of Fort Mason.[6][7][8] Originally named Punta Medanos and Punta de San José by the Spanish settlers, it was renamed Black Point after 1849. Black Point was named for the abundance of dark-colored California bay laurel trees that grew on the bluff.[7][9][10] The shoreline of Black Point is the last remaining section of original coastline in San Francisco east of the Golden Gate Bridge.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

Spanish and Mexican eras

[edit]

In 1797, the Spanish Presidio of San Francisco constructed the Bateria de Yerba Buena at Punta Medanos (now called Black Point) as an artillery battery to provide additional protection to the Yerba Buena anchorage. The site was only briefly occupied and was abandoned by 1806.[11][12]

Private ownership by John C. Frémont

[edit]

The nucleus of Fort Mason was a private property owned by John C. Frémont, the explorer of the western U.S., who also spearheaded the conquest of California from Mexico, and ran as the first presidential nominee of the extant Republican Party in 1856. As alleged in a 1968 federal lawsuit[13] filed by his descendants over the 70-acre parcel then at issue, Frémont bought a 13.5-acre property in the mid-1850s for $42,000, and then improved it by about $40,000.

Appointed a major general in the Union army at the start of the Civil War, Frémont’s repeated serious conflicts with President Lincoln led him to resign by late 1862. In 1863, the government seized the property without payment, by executive order of Lincoln, on the grounds it was needed for the war effort. Frémont would again contest the US presidency in 1864, running as the candidate of Radical Democracy Party, only resigning the effort when Lincoln fired a political enemy in his cabinet as a concession.

The 1968 lawsuit was perhaps the last shot of a century-long legal struggle[14] to obtain compensation for the seized realty. In 1870, the government returned property to 49 parties in the vicinity, but not to Frémont and a few others. At that time, Frémont was still very preoccupied with enough of the vast fortune he had made through gold-mining before the Civil War that the matter was unlikely of concern to him; but by 1872[15] he was in grave financial trouble he would never escape before his death in 1890. Over the years, at least 24 Congressional committees would vote to compensate Frémont, and finally in February 1898 President William McKinley signed a bill directing that the court of claims fix the compensation due. But in 1968 the Frémont heirs complained it had failed to carry out this direction, with John Frémont then recently dead and his widow Jessie over 70 years old.

The fort as government property

[edit]

The Civil War prompted the construction of several coastal defense batteries located inside the Golden Gate. Initially these defenses were built as temporary wartime structures rather than permanent fortifications and one of these was constructed in 1864 at Point San Jose, as the location of Upper Fort Mason was then known. A breast-high wall of brick and mounts for six 10-inch (250 mm) Rodman cannons and six 42-pounder guns were built on the site. Excavation in the early 1980s uncovered the well-preserved remains of the western-half of the temporary battery, and it has now been restored to its condition during the Civil War.[16]

George Mason University (GMU) is a public research university in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. Located in Northern Virginia near Washington, D.C., the university is named in honor of George Mason, a Founding Father of the United States.[9]

In 2018, a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit revealed that conservative donors, including the Charles Koch Foundation and Federalist Society, were given direct influence over faculty hiring decisions at the university’s law and economics schools. GMU President Ángel Cabrera acknowledged that the revelations raised questions about the university’s academic integrity and pledged to prohibit donors from sitting on faculty selection committees in the future.[37]

The Fairfax Resolves were a set of resolutions adopted by a committee in Fairfax County in the Colony of Virginia on July 18, 1774, in the early stages of the American Revolution. Written at the behest of George Washington and others, they were authored primarily by George Mason. The resolutions rejected the British Parliament’s claim of supreme authority over the American colonies. More than thirty counties in Virginia passed similar resolutions in 1774, “but the Fairfax Resolves were the most detailed, the most influential, and the most radical.”[1]

English Civil War

[edit]

“Cavalier” is chiefly associated with the Royalist supporters of King Charles I in his struggle with Parliament in the English Civil War. It first appears as a term of reproach and contempt, applied to Charles’ followers in June 1642:

1642 (June 10) Propositions of Parlt. in Clarendon v. (1702) I. 504 Several sorts of malignant Men, who were about the King; some whereof, under the name of Cavaliers, without having respect to the Laws of the Land, or any fear either of God or Man, were ready to commit all manner of Outrage and Violence. 1642 Petition Lords & Com. 17 June in Rushw. Coll. III. (1721) I. 631 That your Majesty..would please to dismiss your extraordinary Guards, and the Cavaliers and others of that Quality, who seem to have little Interest or Affection to the publick Good, their Language and Behaviour speaking nothing but Division and War.[2]

At the end of the First Civil War, Astley gave his word that he would not take up arms again against Parliament and having given his word he felt duty bound to refuse to help the Royalist cause in the Second Civil War; however, the word was coined by the Roundheads as a pejorative propaganda image of a licentious, hard drinking and frivolous man, who rarely, if ever, thought of God. It is this image which has survived and many Royalists, for example Henry Wilmot, 1st Earl of Rochester, fitted this description to a tee.[13] Of another Cavalier, George Goring, Lord Goring, a general in the Royalist army,[14] the principal advisor to Charles II, Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, said:

[He] would, without hesitation, have broken any trust, or done any act of treachery to have satisfied an ordinary passion or appetite; and in truth wanted nothing but industry (for he had wit, and courage, and understanding and ambition, uncontrolled by any fear of God or man) to have been as eminent and successful in the highest attempt of wickedness as any man in the age he lived in or before. Of all his qualifications dissimulation was his masterpiece; in which he so much excelled, that men were not ordinarily ashamed, or ou

Donald Trump is battling America’s elite universities—and winning

The Ivy League sees little point in fighting the federal government in court

Apr 10th 2025|WASHINGTON, DCShare

Editor’s note: On April 14th the Trump administration froze $2.2bn of federal funds for Harvard University after the Ivy League college

Harvard’s DEI Rebrand Will Serve It Well

Students walk towards Sever Hall in Harvard Yard. By Barbara A. Sheehan

By The Crimson Editorial Board

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

3 days ago

Harvard’s latest DEI makeover demonstrates that the best offense is a stalwart defense.

On Monday, Harvard announced two key changes to its diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives: It will rename the Office of Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging to “Community and Campus Life,” and it will no longer fund or host affinity celebrations during Commencement. Given Washington’s grievances with all things DEI, one may assume Harvard is merely doing what some of its compatriot institutions have done — accede to Trump.

Because of Harvard’s unique, full-throated rejection of Trump’s demands, the new moves are far from an empty gesture of submission. Instead, they represent a practical shift in Harvard’s approach, helping to both better define the work of its office and to insulate itself from unnecessary criticism. The changes will shore up Harvard’s image while retaining the more uncontroversial functions of DEI.

As Trump’s incursion against higher education has progressed, schools like Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania have abandoned the language of DEI in appeasement of the White House amid threats of federal funding cuts.

With its filing of a lawsuit against the federal government, Harvard proved its willingness to fight the Trump administration and its wildly overreaching demands — so why make conciliatory schemes now? With a legal battle underway, there is no value in giving in — Harvard has attempted to preserve its independence. These decisions aren’t about appeasing Trump — they are about fighting him.

Like it or not, DEI — or any permutation of those three letters — is controversial. Recent polling suggests that Americans are deeply divided on DEI, with a slim plurality supporting its elimination. After a year and a half of abysmal public relations, the last thing Harvard needs is to further invite criticism from half the American public. What’s more, we don’t need an office labeled “DEI” to have diversity on our campus.

As the White House makes demand after demand, Harvard needs every bit of public goodwill it can muster — seeking to be less divisive could be decisive. We wager many would be surprised to learn that some of the work done by Harvard’s DEI office seems remarkably uncontroversial and worth supporting, as we noted in an editorial last year.

Previous initiatives include a pre-orientation program that gives incoming first-generation and low-income first-years guidance on navigating Harvard and funding for more accurate medical textbooks for various body types that represent the wide range of human body types. There is no reason for such work to fall victim to undeserved criticism, and a rebrand helps ensure it won’t.

As it continues its remodeling of the office, Harvard should strive for increased transparency. Thus far, the University has been unforthcoming with details, only offering language hinting at changes to come. It should tell us precisely what its offices — DEI or by another name — do in order for judgements to be made.

Advertisement

Luckily, we have already seen some judicious pruning of Harvard’s diversity work: the recent announcement that the University will no longer host or fund affinity graduations. To be clear, places for students to gather within their communities are undeniably a good thing — different groups face different challenges at Harvard, and such spaces are a key resource for many. Also, affinity celebrations are not intended to override or replace Commencement — they simply provide a space for students and their families to celebrate.

But Harvard shouldn’t fund them directly. The University specifically allocating funding to affinity celebrations necessitates a litigation: What groups and identities are deserving of their own ceremony? Every Harvard student is unique, so where do we stop?

We hope that the renaming of Harvard’s diversity office and the end of University-funded graduation ceremonies are a signal of a shift in DEI policy. Without divisive branding, common-sense programs can continue without having their name tarred and feathered in the court of public opinion.

By removing fuel from the fires of controversy, Harvard has increased its odds in the public relations sweepstakes. Let’s hope it wins big.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

Have a suggestion, question, or concern for The Crimson Editorial Board? Click here.

Leave a comment