” Americans deserve a government committed to serving every person with equal dignity and respect”

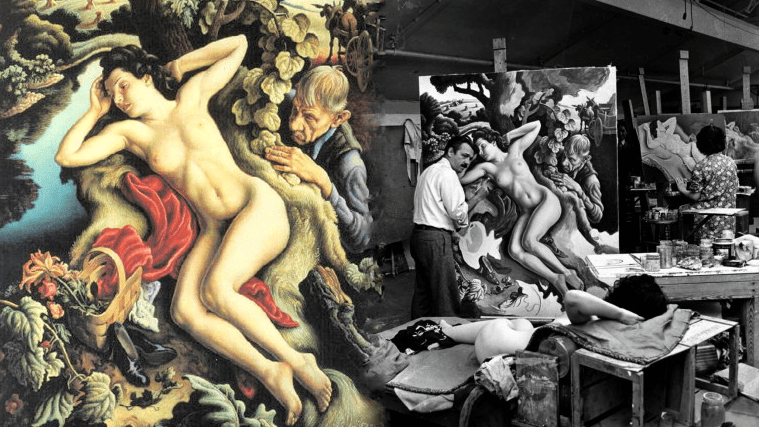

Capturing Beauty

by

John Presco

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

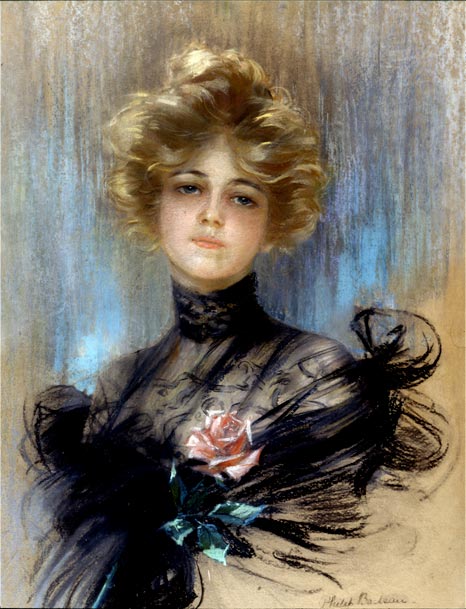

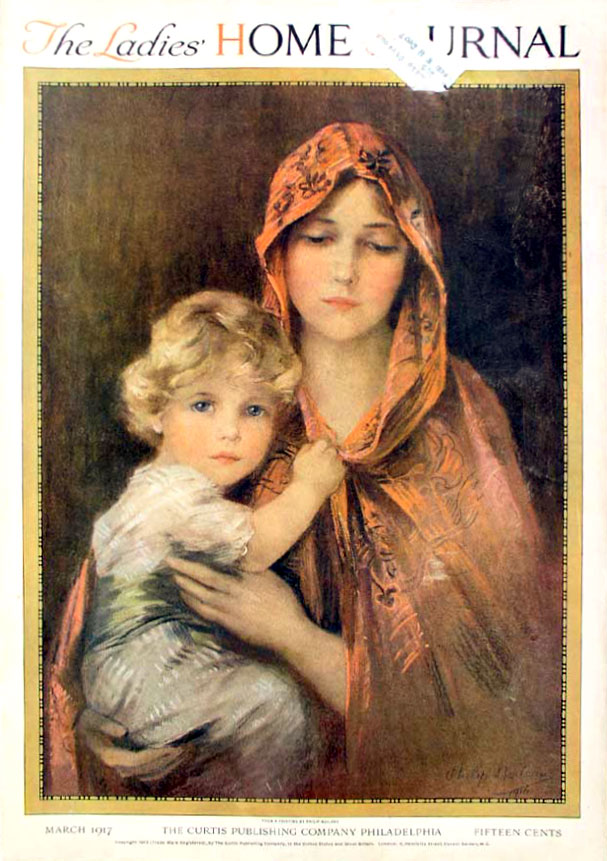

The Benton Family History was written by Maecenas E Benton in 1915. His world famous son was 26. I will research famous Thomas Hart Benton was. Maecenas mentions his relative Philip Bolieau, who was a famous Candain artist – whose beutiful women are sisters to the beautiful women my sister rendered. Christine Rosamond Presco married the muralist Paul Gsrfield Betnon. They gave life to my niece, Drew Taylor Rosamond Benton, who got – BUTCHERED! All that knew her do not believe she inflicted the terrible wounds she came to own. On April 19, 2025, at 9:A.M. I found a painting by Phillip titled ‘Woman With Long Stem Rose’. Was there a model? Was the model – Sarah Benton – his mother? I see Drew looking at me with those foreloin eyes – from beyond the grave. I a,m still in mourning. Drew was in a refrigerator for over twenty days. The police had to track down one cousin while another did not respmd to two letters – to this day!

I have spent hundreds of dollars on Ancestry.Com. Im not alone. Doing your genealogly is somehting 90 million people, do. No one wants to be forgotten. What Ed Ray and his five person team ofhistorians did, was zero in on Senator Thomas Hart Benton, castrate his history, and put a black woman in his place. President Trump signed an executive order making this – KIND OF THING – illegsl. What kind of thing are we talking about? The Supreme Court just made a ruling on this THING, and may do so again. I need an attorney! Jesse Benton, married John Fremont, who are the MODEL TARGETS for the President and Vice President.

Tomorrow is Easter Sunday. I will not spend it with my daughter and grandson thank to a Drunken Tea Party Crazy who father wanted my grandson, because his son could no conceive. How many death threat would I receive if I used AI to put Hattie Redmond’s head on the body of Jesus dying on the cross. I hear her say this – from the home of the dead!

“Hey! Don’t put me in the middle of your crazy-ass famous family feud!”

You can blame this crazy-shit on Joseph Orosco – FOR STARTERS!

Dear Governor Kotek: Today I learned that Joseph Orosco wrote a paper

The latter died in his minority. Sarah married Baron Bolieau, French Minister to the U.S. in the forties, and was the mother of the celebrated artist Philip Bolieau later of New York, now deceased.

And Benton Annex will be named the Hattie Redmond Women and Gender Center. Hattie Redmond was a leader in the struggle for women’s suffrage in Oregon in the early 20th century. The right to vote was especially important to Hattie, who was a black woman living in a state that had black exclusion laws in its constitution. Her work is credited with laying the groundwork for the civil rights movement in Oregon in the mid-twentieth century.

Beginning this academic year, we will develop public educational materials that will share the histories of these three buildings and their previous namesakes. These public displays will be within each of these buildings. As well, we will provide similar information within Gill Coliseum and Arnold Dining Center – two buildings whose names last fall I announced would not change. In the years ahead, OSU will document and display the history of all university buildings within each respective building, on the university website and within a mobile app.

Pursuant to Executive Order 13985 and follow-on orders, nearly every Federal agency and entity submitted “Equity Action Plans” to detail the ways that they have furthered DEIs infiltration of the Federal Government. The public release of these plans demonstrated immense public waste and shameful discrimination. That ends today. Americans deserve a government committed to serving every person with equal dignity and respect, and to expending precious taxpayer resources only on making America great.

This statement covers the direct line from Abner Benton the Englishman who came to America in 1731, down to and including all of the present generation of whom the writer has any knowledge.

Compiled by Maecenas E Benton of Neosho, Missouri, from old family records, from Dorothy Myra Benton’s family bible and from his personal knowledge.

Dated July 22, 1915 (signed) ME Benton

Benton Genealogy

at Thomas Hart Benton Home and Studio State Historic Site

The Bentons were originally established in Lincolnshire England. A branch of the family went to South Wales. In 1731, three brothers, Benton, came from Wales to America. They intended to settle on Chesapeake Bay, but contrary winds drove the ship south, and the brothers landed on Albermarle Sound, North Carolina, whence they went to the uplands and settled at Hillsboro, Orange County, N.C. These brothers were Samuel, Abner, and Jesse. The latter never married. Abner married in Wales, Samuel in North Carolina. This sketch has to do with Abner Benton and heirs. To him was born Jesse B. and Catherine. The latter never married, both born in North Carolina U.S.A. Jesse B. Benton was sent to England and educated. On his return from England, he was appointed (by the Crown), Secretary to the Lord Tryon, Governor of the Province. Afterwards an ugly British General in the Revolutionary War, Jesse B. Benton broke with his chief in the War for American Independence, and was an officer in the American Patriot Army. He, Jesse B. Benton, was married during the War for Independence to Ann Gooch, the daughter of a disreputable English officer under Lord Tryon. Her mother was named Hart and was American born, and Ann Gooch always said, “I came from a family of Harts.” Her cousin Col. Nathaniel Hart was killed at the “River Raisin”, in a battle with British and Indians, during the War of 1812. To the union between Jesse B. Benton and Ann Gooch, there was born Thomas Hart [the Senator], Jesse, Samuel, Nathaniel, Susan, and Catherine Benton. Susan and Catherine never married. In 1793, at the age of 46, Jesse B. Benton died at Hillsboro, N.C.

In 1796, the year Tennessee was admitted to the Union, Jesse B. Benton’s widow Ann, with her family, moved to Tennessee, and settled some forty miles south of Nashville, on land provided by her husband during his life. In 1800 Ann Benton’s sons Thomas H. and Nathaniel returned to North Carolina and entered the State school at Chapel Hill. Neither of them graduated. Of the four brothers Thomas H., Jesse, Samuel, and Nathaniel, the following facts are worthy of record: Samuel married in 1808, a Miss Grundy, and raised six children all born in Carroll County, West Tennessee. Four of these were boys, Nathaniel, Abner, Thomas H., and Samuel (the latter twins) and Catherine and Sarah. Catherine never married. The elder, Nat, went to California and reared a family. Abner died in youth. Thomas H. settled in Iowa, was a Democrat, was a Colonel and Brig. General in the U.S. Army during the Civil War. Was father of Maria Benton, a brilliant woman who married Ben Cable of Illinois and is living. Samuel settled in Holly Springs, Mississippi, reared a family, was twice a Whig Candidate for Congress, was a Confederate Colonel and brevet Brigadier General, was wounded at Resaca, Ga., and died in 1864. Sarah married a Brandt, reared a family and lived and died in St. Louis. Jesse, son of Jesse B. and Ann Benton, married in middle Tennessee, Mary (Polly) Childress, both of whom in old age died near Nashville without children. Thomas Hart, the eldest son was a member of the Tennessee Legislature, a lawyer and a Lieut. Colonel in the War of 1812. An unfortunate break between Generals Jackson, Carroll and Coffee, and Thos. H., Jesse and Nathaniel Benton brothers, resulted in a street duel in Nashville, in September 1813, in which General Jackson and General Carroll were both shot. In 1814 Thos. H. and Nathaniel moved to the Territory of Missouri. Thos. Hart Benton was elected one of the two first United States Senators for Missouri, and served thirty consecutive years, followed by two years in the lower House of Congress. After becoming a Senator he married a daughter of Governor McDowell of Virginia. To this union were born: Sarah, Mary, Jesse Ann, Elizabeth, and Randolph Benton. The latter died in his minority. Sarah married Baron Bolieau, French Minister to the U.S. in the forties, and was the mother of the celebrated artist Philip Bolieau later of New York, now deceased. Mary married a Mr. Jacobs of Jefferson County, Kentucky, an extensive Planter. Jesse Ann married Jon C Fremont, a U.S. Lieutenant of French descent, and afterwards the California Pathfinder, and later in 1856 the first Republican Candidate for President, against James Buchanan, and was not supported by Col. Benton, his father-in-law. Fremont was a Major General U.S.A. in the Civil War. Fremont and Jesse Ann Benton, had born to them John C. (who was a U.S. Naval Captain), and Lilly, who never married but lived to be sixty years old. John C. Jr., died a Captain and has a son John C. now a Captain in the U.S. Navy, and two girls not married. Elizabeth married Commodore Jones, U.S.N. and died in Florence, Italy in 1903.

Nathaniel Benton (our direct ancestor), was born in February 1788, in Hillsboro, Orange County, North Carolina, moved with his mother and family to middle Tennessee in 1796, spent afterwards two years in the North Carolina University and in 1810 married Dorothy Myra Branch, daughter [cousin] of Governor Branch of North Carolina. To this union were born Nathaniel in 1811, Alfred in 1814, Columbus in 1819, Abner in 1816, Susan in 1822, Thomas Hart in 1825, Rufus in 1829, and Maecenas in 1831. Nathaniel and Alfred were born in middle Tennessee; Abner, Columbus and Susan were born in Jefferson County, Missouri; Thomas Hart, Rufus and Maecenas were born in Dyer County, Tennessee. The elder of this family Nat Benton, spent two years at West Point Military Academy, resigned, and with his mother’s family (his father Nat Benton having died in 1833) moved to Texas in October 1835, and settled on the Brazos, near Waco. In February 1836, Nat Benton together with his brother Alfred joined the army of General Sam Houston for the liberation of Texas from Mexican domination. Nat Benton, however, accidentally shot himself in the foot, and came near passing away. Alfred Benton and Ben McCulloch were with Houston at San Jacinto and helped in Texas Independence in 1836. Nat Benton in 1837 returned to Tennessee and married Harriet, the sister of Henry and Ben McCulloch. To this union was born Benjamine Eustace Benton. Nat Benton’s wife died in 1845. In 1853 Nat Benton and son left Dyersburg, Tennessee and went to Texas. Both he and his son Eustace were in the Texas Rangers, and while so engaged Eustace was badly wounded, losing one eye. Captain Nat Benton married again during the’50s to a Miss Harris and children were born to this marriage, but the family history to which I had access did not state how many children, nor where the second Mrs. Benton died.

Nat Benton was a soldier in the Confederate army attaining the rank of Colonel, and was badly wounded at Port Hudson. He returned to Sequing Texas, and lived there till his death which occurred in 1873. His son Capt. Ben Eustace Benton married during the Civil War on April 15 1863, Miss Margaret C. Walker, daughter of General B.W. Walker, and to this union was born Miss Eulalia Benton now living in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Capt Ben E. Benton died at Pine Bluff, Arkansas June 13 1914.

Alfred Benton, second son of Nat and Dorothy M. Benton, after serving in the war for Texas Independence, died in Texas in 1838. Abner the third son, married Mary Ann Wardlaw of Ripley, Lauderdale County, Tenn., and to this union were born eleven children. Fannie, the eldest, married Tom W. Neal at Dyersburg, had two children. Ella N. Crook, now of Little Rock, Arkansas, and Lillian Simpson, and died in 1880. Alfred lives in Louisville, Ky., Ed at Trenton, Tennessee, Hattie at Memphis, Annie at Dyersburg, Tenn., and Minne at Memphis, others all dead. Columbus Benton died in infancy. Susan married one Boggess, had eleven children, none of whom are living to my knowledge, and she died in June 1885.

Thos H. Benton Jr, son of Nat and Dollie Benton, married Mary Ellen Eason, whose father was Carter T. Eason, and mother Ellen, daughter of Gen. Daniel Morgan who defeated Tarleton at the “Cow Pens”. To this union were born Maecenas E., Mary Ellen, Nat (both the latter died in infancy), Jesse Ann, Thomas H. (both of whom died when about grown), Dollie who married Frank E. Miller and had one child named Mary Ruth Miller. Dollie Benton Miller died May 1895. Samuel Abner born in 1863 died in 1894, and Fannie May, who married E.L. Logan and has had two children, Sam Benton and Ernestine. They live in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Maecenas E. Benton, the eldest of this family is a lawyer, born in Obion County, Tennessee, removed to Missouri in 1869. Was two terms State’s attorney, one term as State Representative, one term United States Attorney, and five terms a member of Congress. He was married in 1888 to Elizabeth Wise of Waxahachie, Texas and of Kentucky parentage. To whom were born Thomas Hart [the artist], Mary Elizabeth, Nathaniel Wise, and Mildred Benton, all now grown.

Rufus and Maecenas, the youngest of the children of Nat and Dorothy Benton and brothers of Nat, Abner, and Thomas H., died in youth.

This statement covers the direct line from Abner Benton the Englishman who came to America in 1731, down to and including all of the present generation of whom the writer has any knowledge.

Compiled by Maecenas E Benton of Neosho, Missouri, from old family records, from Dorothy Myra Benton’s family bible and from his personal knowledge.

Dated July 22, 1915 (signed) ME Benton

Situated on a gentle slope called “College Hill” just west of downtown Corvallis, present-day Oregon State University was born with the laying of the cornerstone for the Administration Building in 1887. On July 2, 1888, Oregon’s governor, Sylvester Pennoyer, accepted the new Administration Building (later renamed Benton Hall; present-day Community Hall) and property for the state as a gift of the citizens of Corvallis and Benton County. The first classes were held in the building in the fall of 1888.

Designed by architect Wilbur R. Boothby, of Salem, and costing $25,000 to construct, the building originally housed everything – from all the college’s classrooms, to administrative offices and laboratory space. Materials comprising the College’s library were housed there until 1918, and the President’s Office resided there until 1923. The Music Department took up residence in 1916, and is the building’s sole remaining tenant.

The modern-day clock tower was installed during the university’s centennial; until that time the face was painted on. The Administration Building was renamed Benton Hall in 1947.

JEFFERSON CITY — When artist Thomas Hart Benton returned to Missouri in 1935, his name was almost synonymous with his home state.

Benton had risen to prominence as an American regionalist artist in the 1930s, landing his face on the cover of TIME magazine in 1934.

He was the son of Maecenas Benton, a four-time U.S. congressman from Missouri and named after the first U.S. senator from Missouri, Thomas Hart Benton, his great-great uncle.

With such strong ties to the state and the nation’s eyes on him, Benton’s work was a natural choice to add to the collection of art in the Capitol.

He quickly was commissioned to paint the House Lounge on the building’s third floor. The legislature appropriated $16,000 to pay Benton for his work, the first added to the Capitol since it formally opened in 1924.

Benton’s namesake is depicted in one of four murals in the Missouri Senate chamber and was also depicted as a character during the 1924 pageant celebrating the new Capitol.

In the summer of 1936, Benton began painting what would be the largest piece of art in the Capitol by a Missourian.

When Benton went about deciding what to depict on the mural, he had originally wanted to do a tribute to “Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain, said Bob Priddy, former president of the State Historical Society of Missouri and author of “The Art of the Missouri Capitol: History Canvas, Bronze and Stone.”

Priddy said Benton moved from the Huckleberry Finn idea to focus instead on the people of Missouri after seeing the available space in the House Lounge. Benton named the work “The Social History of Missouri.”

“He didn’t want to do a military history or political history because those are limiting,” Priddy said. “He wanted to do a history of the people of Missouri because he very much believed that the strength of the state is in the people.”

“Politicians come and go, governors come and go, but there’s always the people, and it’s the people who do the work,” Priddy said. “It’s the people who actually shape the society.”

For 14 months before beginning to paint, Benton researched and traveled the state sketching buildings, animals and especially people. Not one face in the mural is the same as another, and many are based on Missourians whom Benton knew.

“The two boys fighting over the watermelon are Benton’s nephews, and the guy with the cigar who’s looking down at them is Sen. (Edward) Barbour, who is the one who introduced the bill to hire Benton to do the mural,” Priddy said.

One of the faces Benton used was that of Harold Brown Jr., son of the then-adjutant general. He is depicted as a naked baby being attended to by a woman in the political rally section.

Benton’s mural does not glorify the state in the same way many of the other Capitol works do. Poverty, slavery and violence are evident in the work, and the mural is far more diverse, including more Black people and women.

“Benton has a somewhat more unvarnished part of our history,” Priddy said. “You don’t see Jesse James in any of the paintings by the original Decoration Commission. They’re all positive views.”

To work freely, Benton rejected the original proposal that would have required him to work under state supervision as other artists had done.

“Without that freedom, I could be channeled into producing a commonplace official work full of trite and mushy symbols,” Benton later said in his autobiography.

The mural can largely be read from left to right, beginning with pioneers moving into the state and trading with Native Americans, and ending with a highlight of the industry present in segments depicting the state’s two largest cities.

Benton includes among the faces of ordinary people a few notable Missourians. Jesse James, for example, is seen robbing a bank and hijacking a train.

Missouri political boss Tom Pendergast is seated prominently in the Kansas City portion of the painting. Pendergast ran a political machine known for bribing police to allow alcohol distribution during Prohibition and for having a hand in the selection of political figures in the state.

When he later went to jail for tax evasion, someone vandalized the mural by writing Pendergast’s prison number on the back of his figure in the mural.

Missouri News Network

Join the MNN Newsletter for a behind-the-scenes look at how the Columbia Missourian, KOMU, KBIA, MBA and Vox magazine build connections across Missouri.Sign up

Benton also addresses environmental issues. Trees frame scenes of Missouri pioneers and a scene of the early lumber industry, but by the political rally scene, all that is left is a chopped trunk.

They are scarcely seen in the painting from then on, reflecting Benton’s view of environmental devastation caused by the forestry industry.

Benton also confronts the state’s history of lead mining, which often included slave labor. He depicts Black laborers working machinery and pulleys. One laborer is being whipped by a white man.

Slavery is also addressed. In one scene, a slave auction is depicted. Elsewhere is a depiction of Missourians driving the Mormon population from the state during the Mormon War because of their religion, which included abolitionist views.

“The Mormon War was one of two or three times in Missouri history when freedom of religion didn’t mean anything,” Priddy said.

Other images of Black Missourians include a white man holding an ax positioned above a Black man in the lumber scene and a Black man leaning on a dead tree at the political rally.

Jordon Chambers, a St. Louis political figure of the time, had objected to the then-governor that the mural did not show how far Black Americans had come since slavery. Benton was called into the governor’s office and disarmed Chambers by asking if he would like to be included in the mural, Priddy said.

Chambers can be seen at the political rally but is separated from the seated white men.

“Black people were no longer slaves, which he’d been portraying on the first two panels,” Priddy said. “They now were part of the political system, but they were not in the political system.”

Tensions during Reconstruction and violence against Black people, including numerous lynchings, are not depicted by Benton.

Benton paints women in a far more active role than had previously been seen in any of the earlier art at the Capitol, although he paints an incomplete picture.

In the political rally scene, men sit idly listening to the speaker, while women prepare food and take care of children. In the scene of an older couple at home, the husband reads the newspaper while the wife rolls dough.

In the St. Louis panel, women can be seen working independently, a group can be seen sewing in a shop, some dance at a restaurant and another woman works at a typewriter.

“Benton just wanted to put a woman in the painting to show that women had broken out of their stereotypical roles and were now productive and parts of the working economy,” Priddy said.

Women did not have a Missouri House representative until 1923 or a member of the Missouri Senate until 1973.

When the painting was finished, some legislators quickly objected to the depiction of the state, specifically the inclusion of a baby’s butt, slavery, the slaughtering of cattle in the Kansas City section and the inclusion of figures such as Jesse James and Pendergast.

According to Priddy, then-Speaker of the House John G. Christy objected to the painting, saying that no one would be able to relax in the room because the figures were jumping off of the walls. Christy tried and failed to pass a resolution to have the paintings redone.

Priddy recounts that the day before the legislative session began, Christy and then-Majority Floor Leader Morris Osborn had breakfast at the Madison House Hotel. Christy loudly ranted, “Have you seen those damnable paintings in the House Lounge?”

Osborn grew increasingly nervous as Christy spoke, finally pointing out to Christy that Benton was sitting behind him at the next table. At that moment a woman approached Benton to get his autograph, complimenting the art.

Benton got up, stood next to Christy and told the woman, “I just heard some comments about art from somebody who knows nothing about it, and if he studied the rest of his life would know even less.”

With that, Benton left the restaurant and Jefferson City and didn’t return for 25 years, returning then to do repairs and cleanings on the mural.

Benton Hall, Benton Annex and Avery Lodge receive new names

July 30, 2018

Oregon State University community members,

I am writing to share my decision regarding new names for three buildings on OSU’s Corvallis campus. These buildings are Avery Lodge, Benton Hall and Benton Annex.

Over the past two years, following scholarly research on the history of these buildings and their namesakes, hundreds of students and OSU employees, as well as community stakeholders and alumni participated in numerous meetings about these buildings and their names. Hundreds more people contributed their thoughts by e-mail, in phone calls, letters, and through a website comment form. Following my decision last fall to change the names of these buildings, the OSU community along with stakeholder committees helped to consider new names for these buildings. (A description of this process, renaming criteria, and the naming policy of the university, along with the research on these buildings and their namesakes, are available on the OSU Building and Place Name website.)

This extensive and thoughtful review was very appropriate.

The names of buildings and places play a very important role in our university. They speak to the history of OSU, the university’s values and mission, and our efforts to create an inclusive community for all. Names also recognize and honor the positive contributions of those associated with the university.

Based upon input gathered, as well as recommendations of the university Architectural Naming Committee, I have decided to provide:

- Avery Lodge with a name that honors the contributions and history of Native Americans within the nearby Willamette Valley and recognizes that federal lands deeded to the state of Oregon to create this university were taken from tribes that have lived in this region for many generations;

- A new name for Benton Hall that recognizes the contributions made by Benton County community residents to create the college in the 1860’s and 70’s that eventually became Oregon State; and

- Benton Annex with a name that appropriately recognizes the building as home to the Women’s Center.

GOING FORWARD:

With the assistance of Siletz tribal leaders and Native American linguists and historians, I have decided that Avery Lodge will be called Champinefu Lodge. In the dialect of the Kalapuya tribe, which inhabited this region, the word Champinefu is translated to mean “At the place of the blue elderberry.” Blue elderberries are specific to the Willamette Valley and the areas around our campus are where Kalapuya tribal members historically would travel to harvest blue elderberries. Phonetically, this name is pronounced: CHOM-pin-A-foo.

Benton Hall will be renamed Community Hall to reflect the contributions of local residents in establishing this university, and helping it reach its 150th anniversary and excel as Oregon’s statewide university.

And Benton Annex will be named the Hattie Redmond Women and Gender Center. Hattie Redmond was a leader in the struggle for women’s suffrage in Oregon in the early 20th century. The right to vote was especially important to Hattie, who was a black woman living in a state that had black exclusion laws in its constitution. Her work is credited with laying the groundwork for the civil rights movement in Oregon in the mid-twentieth century.

These renamings occur as we celebrate OSU150: Oregon State’s 150th anniversary as Oregon’s statewide university. OSU150 runs through October and has offered a rare opportunity to celebrate the university’s past and present, reconcile past problems, and improve for our future. As I have said before, we must acknowledge our past, avoid hypocrisy and recognize the history of those who established this extraordinary university.

Beginning this academic year, we will develop public educational materials that will share the histories of these three buildings and their previous namesakes. These public displays will be within each of these buildings. As well, we will provide similar information within Gill Coliseum and Arnold Dining Center – two buildings whose names last fall I announced would not change. In the years ahead, OSU will document and display the history of all university buildings within each respective building, on the university website and within a mobile app.

I thank everyone who has participated in this important process. Moreover, I thank those who will continue to be engaged as we document the histories of other buildings. Through these many efforts, including OSU150 and the university’s update of its strategic plan, we will remain mindful of the university’s history, as well as its values and mission of inclusive service to our community and all Oregonians.

Sincerely,

Edward J. Ray

President

Oregon State University community members,

I am writing to share my decision regarding new names for three buildings on OSU’s Corvallis campus. These buildings are Avery Lodge, Benton Hall and Benton Annex.

Over the past two years, following scholarly research on the history of these buildings and their namesakes, hundreds of students and OSU employees, as well as community stakeholders and alumni participated in numerous meetings about these buildings and their names. Hundreds more people contributed their thoughts by e-mail, in phone calls, letters, and through a website comment form. Following my decision last fall to change the names of these buildings, the OSU community along with stakeholder committees helped to consider new names for these buildings. (A description of this process, renaming criteria, and the naming policy of the university, along with the research on these buildings and their namesakes, are available on the OSU Building and Place Name website.)

This extensive and thoughtful review was very appropriate.

The names of buildings and places play a very important role in our university. They speak to the history of OSU, the university’s values and mission, and our efforts to create an inclusive community for all. Names also recognize and honor the positive contributions of those associated with the university.

Based upon input gathered, as well as recommendations of the university Architectural Naming Committee, I have decided to provide:

Avery Lodge with a name that honors the contributions and history of Native Americans within the nearby Willamette Valley and recognizes that federal lands deeded to the state of Oregon to create this university were taken from tribes that have lived in this region for many generations;

A new name for Benton Hall that recognizes the contributions made by Benton County community residents to create the college in the 1860’s and 70’s that eventually became Oregon State; and

Benton Annex with a name that appropriately recognizes the building as home to the Women’s Center.

GOING FORWARD:

With the assistance of Siletz tribal leaders and Native American linguists and historians, I have decided that Avery Lodge will be called Champinefu Lodge. In the dialect of the Kalapuya tribe, which inhabited this region, the word Champinefu is translated to mean “At the place of the blue elderberry.” Blue elderberries are specific to the Willamette Valley and the areas around our campus are where Kalapuya tribal members historically would travel to harvest blue elderberries. Phonetically, this name is pronounced: CHOM-pin-A-foo.

Benton Hall will be renamed Community Hall to reflect the contributions of local residents in establishing this university, and helping it reach its 150th anniversary and excel as Oregon’s statewide university.

And Benton Annex will be named the Hattie Redmond Women and Gender Center. Hattie Redmond was a leader in the struggle for women’s suffrage in Oregon in the early 20th century. The right to vote was especially important to Hattie, who was a black woman living in a state that had black exclusion laws in its constitution. Her work is credited with laying the groundwork for the civil rights movement in Oregon in the mid-twentieth century.

These renamings occur as we celebrate OSU150: Oregon State’s 150th anniversary as Oregon’s statewide university. OSU150 runs through October and has offered a rare opportunity to celebrate the university’s past and present, reconcile past problems, and improve for our future. As I have said before, we must acknowledge our past, avoid hypocrisy and recognize the history of those who established this extraordinary university.

Beginning this academic year, we will develop public educational materials that will share the histories of these three buildings and their previous namesakes. These public displays will be within each of these buildings. As well, we will provide similar information within Gill Coliseum and Arnold Dining Center – two buildings whose names last fall I announced would not change. In the years ahead, OSU will document and display the history of all university buildings within each respective building, on the university website and within a mobile app.

I thank everyone who has participated in this important process. Moreover, I thank those who will continue to be engaged as we document the histories of other buildings. Through these many efforts, including OSU150 and the university’s update of its strategic plan, we will remain mindful of the university’s history, as well as its values and mission of inclusive service to our community and all Oregonians.

Sincerely,

Edward J. Ray

President

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Maecenas Eason Benton | |

|---|---|

| From Volume 1 of 1899’s Autobiographies and Portraits of the President, Cabinet, Supreme Court, and Fifty-fifth Congress | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri‘s 15th district | |

| In office March 4, 1897 – March 3, 1905 | |

| Preceded by | Charles Germman Burton |

| Succeeded by | Cassius M. Shartel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 29, 1848 Dyersburg, Tennessee |

| Died | April 27, 1924 (aged 76) Springfield, Missouri |

| Resting place | Odd Fellows Cemetery, Neosho, Missouri |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Children | Thomas Hart Benton |

| Alma mater | Saint Louis University |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States of America |

| Branch/service | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Maecenas Eason Benton (January 29, 1848 – April 27, 1924) was a U.S. Representative from Missouri. He was the father of Thomas Hart Benton, who gained fame as a painter of the American Scene. His uncle was Thomas Hart Benton, one of the first two United States Senators elected from Missouri.[1]

Biography

[edit]

Born near Dyersburg, Tennessee, Benton attended two west Tennessee academies and Saint Louis University. He was graduated from the Cumberland School of Law at Cumberland University, Lebanon, Tennessee, in 1870. He served in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War. He was admitted to the bar and commenced practice in Neosho, Missouri. He served as prosecuting attorney of Newton County, Missouri, from 1878 to 1884 and subsequently the United States attorney from March 1885 to July 1889. He also served as delegate to the 1896 Democratic National Convention. On June 24, 1888 he married Elizabeth Wise of Waxahachie, Texas.

Congressional career

[edit]

Benton was elected as a Democrat to the 55th, 56th, 57th, and 58th congresses (March 4, 1897 – March 3, 1905).[2] An unsuccessful candidate for re-election in 1904 to the 59th Congress, he resumed his law practice in Neosho, Missouri, and served as member of the State constitutional conventions in 1922 and 1924. He died in Springfield, Missouri, April 27, 1924 of throat cancer and was interred in the Odd Fellows Cemetery, Neosho, Missouri. He is pictured in the 1939 Neosho centennial mural, in Neosho, Missouri, by James Duard Marshall.

Oregon State to rename Avery, Benton buildings; retain Gill Coliseum, Arnold Dining names

by News StaffMon, November 27th 2017 at 1:13 PM

Updated Mon, November 27th 2017 at 1:18 PM

Oregon State University’s Gill Coliseum, September 14, 2017. (SBG)

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Oregon State will change the names of a building named for an advocate of slavery and two other buildings that share a name with a 19th century U.S. lawmaker who opposed abolishing slavery and favored removing Native Americans from Western lands, President Ed Ray announced Monday.

But Ray favors retaining the names of a former OSU president who was born into a slave-owning family and served in the Confederate army.

And the university president said he found no evidence to support contentions that the namesake of the school’s basketball arena – Gill Coliseum – held discriminatory viewpoints.

The University of Oregon conducted a similar review, which resulted in stripping the name of a former Ku Klux Klan leader from a residence hall.

he announcement is the culmination of two years of public input and scholarly review, Ray said.

“By exploring our past, we will recognize that everything and everyone who preceded us, helped get us to who and where we are today,” Ray said. “This knowledge will guide us to improve. And in doing so, reconcile past injustices and provide for greater future inclusivity and success for all.”

Ray explained his thinking in detail on each of the 5 buildings:

AVERY LODGE:

The preponderance of evidence gathered by the scholar’s report and this naming review process – and shared by other historians in the past – indicates that Joseph C. Avery’s views and political engagement in the 1850’s to advance slavery in Oregon are inconsistent with Oregon State’s values. At the time, he was linked to the Occidental Messenger, a pro-slavery, Corvallis-based publication. I recognize that Joseph C. Avery made important contributions in the early days to help establish Corvallis College, which became what is now OSU. I also am mindful that over the past decades, other members of the Avery family have contributed to OSU and I thank them for their support of the university. However, it is my decision that going forward, OSU will no longer recognize Joseph C. Avery’s legacy with the name of a university building.

ARNOLD DINING CENTER:

It is clear from the scholar’s report and naming review process that Benjamin Lee Arnold, president of Corvallis College and Oregon Agricultural College from 1872-1892, was born into a Virginia family that owned slaves and benefitted from slavery. Benjamin Lee Arnold did not own slaves himself. It is also true that as a college student, he spent time studying slavery as an economic system. He also served within the Confederate Army – although it appears that he was frequently ill during the Civil War and details of his service are unclear. As president of Corvallis College, he led the institution to stability during a very difficult, formative time. He served as an administrator, taught classes, and contributed to fundraising so that the college could maintain its land grant status under the Morrill Act. It is not clear whether Arnold privately or publicly held or espoused discriminatory views, however, his contributions to the institution are evident and notable. As president, the college grew and women students and faculty were welcomed, nearly a century before Ivy League schools enrolled women. The college admitted and graduated its first Native American students during this time, as well. When the college changed from a church-related school to a public college in the mid-1880s, the new oversight board retained President Arnold in his position. It is my judgment that the preponderance of evidence supports retaining the name of Arnold Dining Center.

BENTON HALL:

The university sought to honor the residents of Benton County in 1947 by naming OSU’s first building, Benton Hall. History shows that members of the community remarkably raised a significant amount of funds for the construction of the building in January 1887. This same community has since supported the university and its mission. In contrast, according to the scholar’s report and naming review process, the name of this building does not seek to honor former Missouri U.S. Sen. Thomas Hart Benton, who in the 1820’s through the 1850’s, was a national architect of westward expansion and promoter of Manifest Destiny, and for whom Benton County is named. During that era, Benton supported federal legislation to remove Native Americans from their tribal lands and, while he was opposed to extending slavery into western states, he was not in favor of abolishing slavery elsewhere. The current name of the building does not make this distinction clear. It is my judgment that the name of Benton Hall should be changed to a name that honors the contributions of community and county residents who believed in and invested in higher education early on. Thanks to their initial leadership and contributions, Oregon State University has endured and pursued its mission.

BENTON ANNEX:

I find that the 1972 naming of this building and its connection to Benton Hall lacks an explanation. While the building has been an important part of the university since 1882, its current role serving as the OSU Women’s Center was not determined until 1973. Going forward, this building should have a new name that recognizes the important role that this center contributes to Oregon State.

GILL COLISEUM:

It is my decision that this athletics center will continue to be named in honor of Amory T. “Slats” Gill, who served from 1928-64 as Oregon State’s basketball coach and eventually as athletic director. I find that the scholars’ report and naming review process offers no evidence that Gill deliberately sought to keep the Oregon State men’s basketball team from becoming integrated. I also find no evidence that he held or expressed discriminatory views about African-Americans. It appears Gill was a product of his time regarding the style of play of his teams, which he perfected. He coached at Oregon State during an era in which few African-Americans attended this institution, and those who did faced frequent discrimination. This was a troubled era in the university’s history, but I do not find that Gill supported such a lack of inclusivity. In fact, the historical review indicates he tried unsuccessfully to recruit several African-American student-athletes. While a tough taskmaster for all of his players, Gill also was active in the Corvallis community, serving on the school board and helping lead community and university organizations.

Ray directed the University’s Architectural Naming Committee to “undertake a process that engages the overall Oregon State University community to consider and to recommend to me new names for these three buildings” this winter.

He also asked the committee to lead an effort to gather and document the history of all OSU buildings and their namesakes as the University celebrates its 150th year.

Community Hall (formerly the Administration Building, then Benton Hall) was the first building constructed on the Oregon State University campus in Corvallis, Oregon and the oldest structure on its campus today. Its original name was simply the “Administration Building” while the university itself was using the name under which it was first organized: Oregon State Agricultural College. It is situated on a gentle slope called “College Hill,” just west of the city’s commercial center on the west bank of the Willamette River, there anchoring what remains of the school’s original buildings on the “Lower Campus” (given with current names and years built): Apperson Hall (1899), Benton Annex (1892), Education Hall (1902) and Gladys Valley Gymnastics Center (1898).

History

[edit]

In 1860 a lien was placed on the first building to occupy the site, by a carpenter who had not been paid for his work. The ensuing sheriff’s sale resulted in ownership of the building, the land and the school operating there (Corvallis College) transferring to Rev. Orceneth Fisher on behalf of the Methodist Episcopal Church South, where he served as pastor. By 1885, calls from local leaders were growing loud to convert it to a state institution which would be eligible for federal funds under the Morrill Land-Grant Acts and the church agreed to relinquish control.[3] In response, the Oregon State Legislature passed an act that reorganized the school as the state’s agricultural college, but skeptical of the actual awarding of land-grant status it decided to require the citizens of Benton County to bear the full costs for the construction of a suitable building to house its offices, which the act required to be no less than $25,000 (equivalent to $675,000 in 2020), and if successful the building would become de jure property of the state upon completion through eminent domain.

The 1880 census had reported only 1,400 households within the entire county, but less than two years later the sum had been raised, permits secured and construction began on the building still standing today, largely unchanged, as Community Hall.[4] The cornerstone was laid by the Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Oregon on August 17, 1887[5] and it officially opened in September 1889 at the start of the school’s final academic year as the State Agricultural College of Oregon; it opened for the 1890 term as simply the Oregon Agricultural College.[6][7]

On October 28, 1987, Governor Neil Goldschmidt signed a proclamation declaring the day as “Benton Hall Day”.[5]

Benton Hall was renamed Community Hall in November 2017.[8][9]

Oregon State student sues Trump administration for revoking visa

By Troy Brynelson (OPB)

April 17, 2025 7:10 a.m.

Aaron Ortega Gonzalez says he’s never committed a crime despite ICE officials’ claims.

An international student at Oregon State University has filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration after it revoked his legal status earlier this month.

Aaron Ortega Gonzalez is a Mexican citizen and a PhD student at Oregon State, where he’s been researching the impact of wildfires on ranchlands. Ortega Gonzalez has reportedly been given no reason why the federal government ended his legal status.

According to the lawsuit, filed in the U.S. District Court of Oregon on Wednesday, officials with Immigration and Customs Enforcement went into a government-controlled database of student visas on April 4 and terminated Ortega Gonzalez’s status.

Immigration officials wrote in the database: “individual identified in criminal records check and/or has had their VISA revoked,” the filing said.

According to the lawsuit, Oregon State University’s Offices of International Services emailed Ortega Gonzalez on April 8 alerting him to the change in his status. University officials did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

THANKS TO OUR SPONSOR:

The 32-year-old has not been detained, but was told that he is “expected to depart the United States immediately.” The lawsuit asks the court to reinstate Ortega Gonzalez’s status.

Ortega Gonzalez was born and raised in Mexico, where he obtained his undergraduate degree. He applied for and received a student visa in 2021. He received a master’s degree at a university in Texas before moving to Corvallis to pursue his doctorate.

Attorneys for Ortega Gonzalez say he has never committed a crime or a traffic violation. He’s never withdrawn from his studies — which can result in visa termination — nor has he “engaged in unauthorized employment.”

“Not only was Aaron unilaterally stripped of his status and denied due process rights, as it violates the law, the critical research he was working on has been halted,” Ortega Gonzalez’s attorneys said in a press release.

ICE officials declined to comment, citing the litigation.

Three legal teams are representing him: the ACLU of Oregon, the legal nonprofit Innovation Law Lab, and immigration law firm Nelson Smith LLP.

The move comes as the federal government continues to target international students across the United States by quashing their visas. That includes four students at the University of Oregon and two students at Portland State University.

Publicly, many of the federal governments’ moves have ostensibly aimed at ending antisemitism. On April 9, Homeland Security officials announced the agency has begun monitoring social media activity of people seeking “lawful permanent resident status,” as well as international students, for posts that “support antisemitic terrorism.”

Tiffany Camhi contributed to this report.

Harriet “Hattie” Redmond (1862-1952)

“Mrs. Redmond says that while there were 2500 colored women of voting age in this city the [Colored Women’s Equal Suffrage Club] has only 14 members… She attributed this largely to the influence of their husbands and ignorance of the benefits to be derived from the franchise.” – The Oregonian, 1912

“Mrs. Redmond says that while there were 2500 colored women of voting age in this city the [Colored Women’s Equal Suffrage Club] has only 14 members… She attributed this largely to the influence of their husbands and ignorance of the benefits to be derived from the franchise.” – The Oregonian, 1912

The daughter of freed slaves, Redmond resided in Portland during a time when Oregon’s laws and constitution were written to prevent Black Americans from living or owning property in the state. Undeterred, Redmond struggled for acceptance and representation for Black women in Oregon and beyond. Portland society barred Redmond from the women’s rights groups frequented by white suffragists. She instead organized meetings and lectures on suffrage at Mt. Olivet First Baptist Church and in 1912 served as president of the Colored Women’s Equal Suffrage Association.

Like many other women of color, Redmond’s life and contributions to suffrage were virtually unknown until the 21st century. Widowed in 1907, she made a living as a hairdresser, domestic worker, and a duster in a department store until becoming a janitor for Oregon’s U.S. District Court in 1910 – a post she held for 29 years. Historians in Portland uncovered her records in 2012 while conducting research during the centennial of Oregon woman suffrage. Celebrated only after her death, Redmond’s grave at Lone Fir Cemetery now bears the inscription “Black American Suffragist.” Oregon State University students now pursue women’s studies in the Hattie Redmond Women and Gender Center.

In 1856, Frémont (age 43) became the first presidential candidate of the newly-formed Republican Party. The Republicans, whose party had been established in 1854, were united in their opposition to the Pierce Administration and the spread of slavery into the West.[110] Initially, Frémont was asked to be the Democratic candidate by former Virginia Governor John B. Floyd and the powerful Preston family.[98] Frémont announced that he was for Free Soil Kansas and was against the enforcement of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law.[98]

The campaign was particularly abusive, as the Democrats attacked Frémont’s illegitimate birth and alleged Frémont was Catholic.[98] In a counter-crusade against the Republicans, the Democrats ridiculed Frémont’s military record and warned that his victory would bring civil war. Much of the private rhetoric of the campaign focused on unfounded rumors regarding Frémont – talk of him as president taking charge of a large army that would support slave insurrections, the likelihood of widespread lynchings of slaves, and whispered hope among slaves for freedom and political equality.[115][113]

Philip Boileau

1864–1917

Philip Boileau was born in Canada in 1864 to a career diplomat father, serving under Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, and the daughter of the noted United States Senator from Missouri, Thomas Hart Benton. Traveling for most of his early life, the Boileau family moved to England in 1871, where Philip was educated. At the age of 23, he moved to Italy to study art and married a Russian singer, who unfortunately passed a short time later.

In 1897, Philip Boileau emigrated to Baltimore, MD, and found success in painting formal portraits of the city’s high society. In 1900 he moved to Philadelphia, where he met his greatest inspiration, Emily Gilbert. During this time his artworks found greater recognition and were exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Two years later he moved to New York, the center of the expanding art market, and in 1903 he created his first commercially successful illustration, “Peggy,” a head-and-shoulders portrait Emily Gilbert. These beautiful portraits of Emily became his first commercial success, and in 1907, the two married amid Boileau’s flourishing career. In 1915, he placed second in Pictorial Review Magazine’s “Artist of the Year” contest.

In 1917, just fourteen years after painting “Peggy”, Boileau contracted pneumonia and died at his home on Long Island, Douglas Manor at just 53. Had he lived longer his total artistic output would have been significantly larger and he would most likely have become as famous as Charles Dana Gibson or Harrison Fisher.

Ending Radical And Wasteful Government DEI Programs And Preferencing

The White House

January 20, 2025

By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered:

Section 1. Purpose and Policy. The Biden Administration forced illegal and immoral discrimination programs, going by the name “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI), into virtually all aspects of the Federal Government, in areas ranging from airline safety to the military. This was a concerted effort stemming from President Biden’s first day in office, when he issued Executive Order 13985, “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government.”

Pursuant to Executive Order 13985 and follow-on orders, nearly every Federal agency and entity submitted “Equity Action Plans” to detail the ways that they have furthered DEIs infiltration of the Federal Government. The public release of these plans demonstrated immense public waste and shameful discrimination. That ends today. Americans deserve a government committed to serving every person with equal dignity and respect, and to expending precious taxpayer resources only on making America great.

Sec. 2. Implementation. (a) The Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), assisted by the Attorney General and the Director of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), shall coordinate the termination of all discriminatory programs, including illegal DEI and “diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility” (DEIA) mandates, policies, programs, preferences, and activities in the Federal Government, under whatever name they appear. To carry out this directive, the Director of OPM, with the assistance of the Attorney General as requested, shall review and revise, as appropriate, all existing Federal employment practices, union contracts, and training policies or programs to comply with this order. Federal employment practices, including Federal employee performance reviews, shall reward individual initiative, skills, performance, and hard work and shall not under any circumstances consider DEI or DEIA factors, goals, policies, mandates, or requirements.

(b) Each agency, department, or commission head, in consultation with the Attorney General, the Director of OMB, and the Director of OPM, as appropriate, shall take the following actions within sixty days of this order:

(i) terminate, to the maximum extent allowed by law, all DEI, DEIA, and “environmental justice” offices and positions (including but not limited to “Chief Diversity Officer” positions); all “equity action plans,” “equity” actions, initiatives, or programs, “equity-related” grants or contracts; and all DEI or DEIA performance requirements for employees, contractors, or grantees.

(ii) provide the Director of the OMB with a list of all:

(A) agency or department DEI, DEIA, or “environmental justice” positions, committees, programs, services, activities, budgets, and expenditures in existence on November 4, 2024, and an assessment of whether these positions, committees, programs, services, activities, budgets, and expenditures have been misleadingly relabeled in an attempt to preserve their pre-November 4, 2024 function;

(B) Federal contractors who have provided DEI training or DEI training materials to agency or department employees; and

(C) Federal grantees who received Federal funding to provide or advance DEI, DEIA, or “environmental justice” programs, services, or activities since January 20, 2021.

(iii) direct the deputy agency or department head to:

(A) assess the operational impact (e.g., the number of new DEI hires) and cost of the prior administration’s DEI, DEIA, and “environmental justice” programs and policies; and

(B) recommend actions, such as Congressional notifications under 28 U.S.C. 530D, to align agency or department programs, activities, policies, regulations, guidance, employment practices, enforcement activities, contracts (including set-asides), grants, consent orders, and litigating positions with the policy of equal dignity and respect identified in section 1 of this order. The agency or department head and the Director of OMB shall jointly ensure that the deputy agency or department head has the authority and resources needed to carry out this directive.

(c) To inform and advise the President, so that he may formulate appropriate and effective civil-rights policies for the Executive Branch, the Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy shall convene a monthly meeting attended by the Director of OMB, the Director of OPM, and each deputy agency or department head to:

(i) hear reports on the prevalence and the economic and social costs of DEI, DEIA, and “environmental justice” in agency or department programs, activities, policies, regulations, guidance, employment practices, enforcement activities, contracts (including set-asides), grants, consent orders, and litigating positions;

(ii) discuss any barriers to measures to comply with this order; and

(iii) monitor and track agency and department progress and identify potential areas for additional Presidential or legislative action to advance the policy of equal dignity and respect.

Sec. 3. Severability. If any provision of this order, or the application of any provision to any person or circumstance, is held to be invalid, the remainder of this order and the application of its provisions to any other persons or circumstances shall not be affected.

Sec. 4. General Provisions. (a) Nothing in this order shall be construed to impair or otherwise affect:

(i) the authority granted by law to an executive department or agency, or the head thereof; or

(ii) the functions of the Director of the Office of Management and Budget relating to budgetary, administrative, or legislative proposals.

(b) This order shall be implemented consistent with applicable law and subject to the availability of appropriations.

(c) This order is not intended to, and does not, create any right or benefit, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law or in equity by any party against the United States, its departments, agencies, or entities, its officers, employees, or agents, or any other person.

THE WHITE HOUSE,

January 20, 2025.

Photo by Carl Van Vechten. Public domain. Via Wikimedia Commons at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tom_benton.jpg EditEdit profile photo

| Thomas Hart Benton (1889 – 1975) | |

| Birthdate: | April 15, 1889 |

| Birthplace: | Neosho, Newton County, Missouri, United States |

| Death: | January 19, 1975 (85) while working in his studio, Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri, United States  |

| Immediate Family: | Son of Rep. Maecenas Eason Benton, U.S. Congress and Elizabeth Benton Husband of Rita Benton Father of Thomas Piacenza Benton and Jessie Benton Brother of Mary Elizabeth Benton; Nathaniel Wise Benton and Mildred Benton |

|---|---|

| Managed by: | Private User |

| Last Updated: | February 26, 2025 |

Historical records matching Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton in U.S. Social Security Death Index (SSDI)

Thomas Hart Benton in Biographical Summaries of Notable People

Thomas Hart Wise in MyHeritage family trees (Cole Web Site)

Thomas Hart Benton in MyHeritage family trees (Turner Web Site)

Thomas Hart Wise in MyHeritage family trees (Cole Web Site)

Thomas Hart Wise in MyHeritage family trees (Cole Web Site)

Thomas Hart Benton in Compilation of Famous Artists

Thomas Hart Benton in MyHeritage family trees (Prather Web Site)

Thomas Hart Benton in Famous People Throughout History

Thomas H Benton in 1950 United States Federal Census

Thomas Hart Benton in Lawrence Journal-World – Jan 23 1975

Thomas Hart Benton in Daytona Beach Morning Journal – Jan 21 1975

Immediate Family

- Rita Bentonwife

- Thomas Piacenza Bentonson

- Jessie Bentondaughter

- Source: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/114605723/elizabeth-bentonElizabeth Bentonmother

- Photo from The Neale Company (Washington, DC), publisher. – “Autobiographies and Portraits of the President, Cabinet, Supreme Court, and Fifty-fifth Congress”. Volume 1. 1899. Page 329. Public domain. Via Wikimedia Commons at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maecenas_Eason_Benton_(Missouri_Congressman).jpgRep. Maecenas Eason Benton, U.S….father

- Mary Elizabeth Bentonsister

- Nathaniel Wise Bentonbrother

- Mildred Bentonsister

About Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton (April 15, 1889 – January 19, 1975) was an American painter, muralist, and printmaker. Along with Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry, he was at the forefront of the Regionalist art movement. The fluid, sculpted figures in his paintings showed everyday people in scenes of life in the United States.

His work is strongly associated with the Midwestern United States, the region in which he was born and which he called home for most of his life. He also studied in Paris, lived in New York City for more than 20 years and painted scores of works there, summered for 50 years on Martha’s Vineyard off the New England coast, and also painted scenes of the American South and West.

Benton was born in Neosho, Missouri, into an influential family of politicians. He had two younger sisters, Mary and Mildred, and a younger brother, Nathaniel. His mother was Elizabeth Wise Benton and his father, Col. Maecenas Benton, was a lawyer and four times elected as U.S. congressman. Known as the “little giant of the Ozarks”, Maecenas named his son after his own great-uncle, Thomas Hart Benton, one of the first two United States Senators elected from Missouri.

At the age of 33, Benton married Rita Piacenza, an Italian immigrant, in 1922. They met while Benton was teaching art classes for a neighborhood organization in New York City, where she was one of his students. They were married for almost 53 years until Benton’s death in 1975; Rita died eleven weeks after her husband. The couple had a son, Thomas Piacenza Benton (1926-2010), and a daughter, Jessie Benton, (1939-2023), who became a major figure in the Fort Hill Community founded by Mel Lyman; Benton himself was identified as a “benefactor” to the community, giving them “dozens of paintings.” (Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sources

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/25089171

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hart_Benton_%28painter%29

- http://www.house.mo.gov/famous.aspx?fm=5

- Benton, Thomas Hart (1951), An Artist in America, University of Kansas City Press.

- Benton, Thomas Hart (1969), An American in Art: A Professional and Technical Autobiography, University Press of Kansas

- https://kansassampler.org/8wondersofkansas-art/a-thomas-hart-benton…

Philip Boileau and Christine Rosamond

Posted on May 19, 2012 by Royal Rosamond Press

“Christine worked almost exclusively from photographs and

figures she cut from magazines like Vanity Fair and Vogue and

Glamour,” Garth recalls. “That’s why the women in her middle period

were so exquisite – the inspiration for them came from elegant

magazines that set the standard.”

The artist, Philip Boileau, was the son Susan Taylor Virginia McDowell Benton, the sister of Jessie Benton, the daughter of Thomas Hart Benton, whose grandson was the famous artist of the same name, who was the cousin of Garth Benton, who married Christine Rosamond Presco, who is kin to Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor, according to Jimmy Rosamond, the Rosamond Family genealogists.

Elizabeth Taylor appeared on the cover of LIFE magazine, and was on the cover of numerous magazines, as were the beautiful women painted by Boileau, that resemble Rosamond Women. No one, but I, knew of these relations after the death of the world famous artist ‘Rosamond’.

Recently two paintings by Andy Warhol of Liz Taylor sold for a hundred million dollars. ‘The Men In Her Life’ sold for $60,000,000 million dollars. Eddie Fisher is in this Warhol work, he the father of the actress , Carrie Fischer, who wrote a screenplay about my later sister, who is the mother of the artists, Drew Benton.

Christine and Drew are kin to John Fremont who was a co-founder of Republican Party, and its firs Presidential Candidate. Three years ago I registered as a Republican in order to stand in the way of the take over my kindred’s party by the Evangelical Cult. Today, there is a new threat coming from the Mormon Cult who are into Ancestor Worship. Evangelicals call Mitt Romney a cult candidate. The Jewish Defence League is irate about the Mormons baptizing Jews and joining them to their celestial genealogies.

At Hollywood’s Temple Israel, on March 27, 1959, Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor converted to Judaism whose genealogies are found in both books of the Bible. Elizabeth is our Family Madonna, who if alive, would lead Beautiful Women in battle against the Evangelical Mormon Axis of Evil, who wage a War on Women, the elderly, the hungry, and the poor.

Christine Rosamond Benton, and Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor, are in America’s Family Tree, the foremont genealogy of American and Judaic History – not to mention Art History. Jessie and Susan Benton held Salons in San Francisco and Paris. Gottschalk Rosemont, was a the Master of ‘The Falcon’ art college, and was a Renaissance teacher of art and religious history. Liz Taylor and her uncle had fabulous art collections. Garth and Christine Benton, were friends of J.Paul Getty. We are talking about the Rose of the World family Art Dynasty. Consider the Roza Mira prophecy.

Jon Presco

Copyright 2012

Celebrity death and marketability go hand and hand, which could bode well for the unidentified private owner whose sale of an iconic Andy Warhol painting of Elizabeth Taylor was announced Thursday by the auction house Phillips de Pury & Co.

The estimated price for “Liz #5,” painted in 1963, is $20 million to $30 million. Is this a bid to exploit Taylor’s death?

View Elizabeth Rosamond Taylor, Dame’s complete profile:

See if you are related to Elizabeth Rosamond Taylor, Dame

Request to view Elizabeth Rosamond Taylor, Dame’s family tree

When dealing with the salons, historians have traditionally focused upon the role of women within them.[28] Works in the nineteenth and much of the twentieth century often focused on the scandals and ‘petty intrigues’ of the salons.[29] Other works from this period focused on the more positive aspects of women in the salon.[30] Indeed, according to Jolanta T. Pekacz, the fact women dominated history of the salons meant that study of the salons was often left to amateurs, while men concentrated on ‘more important’ (and masculine) areas of the Enlightenment.[31]

Portrait of Mme Geoffrin, salonnière, by Marianne Loir (National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC)Historians tended to focus on individual salonnières, creating almost a ‘great-woman’ version of history that ran parallel to the Whiggish, male dominated history identified by Herbert Butterfield. Even in 1970, works were still being produced that concentrated only on individual stories, without analysing the effects of the salonnières’ unique position.[32] The integral role that women played within salons, as salonnières, began to receive greater – and more serious – study in latter parts of the twentieth century, with the emergence of a distinctly feminist historiography.[33] The salons, according to Carolyn Lougee, were distinguished by ‘the very visible identification of women with salons’, and the fact that they played a positive public role in French society.[34] General texts on the Enlightenment, such as Daniel Roche’s France in the Enlightenment tend to agree that women were dominant within the salons, but that their influence did not extend far outside of such venues.[35]

Never has there been such a wonderous day as today in regards to my

genealogical research. I have found another artist lost in our Family

Tree. Philip Boileau is the son of Baron Gauldree Boileau who married

Susan Benton, the daughter of Senator Thomas Hart Benton, and sister

to Jesse Benton who married the ‘Pathfinder’ and Presidential

candidate, John Freemont. My late sister, the artist Christine

Rosamond Benton, married the cousin of the famous artist, Thomas Hart

Benton, and thus one can find Philip Boileau “the painter of fair

women” in the same family tree as Rosamond, the name she used to sign

her portraits of beautiful and fair women that bare an uncanny

resemblance to her predecessor – though she never saw his work!

This is due no doubt to the work of Gibson of the ‘Gibson Girls’

fame, that we as children admired. A book of Gibson’s work was kept

with magazines from the twenties and thirties wherein were published

the short stories of our grandfather, Royal Reuben Rosamond, who self-

published four novels about the Ozark folks, and like the artist,

Thomas Hart Benton, was good friends with the Ozark historian, Otto

Rayburn.

Philip Boileau self-published his work ‘Peggy’ as it was considered

too innovative. His portrait of a young man ‘Youth’ appeared on the

cover of Post magazine on April 19,1913. I suspect Philip had an

influence on Norman Rockwell who used the same empty spaces that were

peculiar to Philip’s work. As a profound coincidence, these spaces

made my sister famous.

In filling in the blanks, and while doing the Family Tree, I

discovered Philip, he too dying a untimely death at the height of his

success. When one now beholds the work of those who are kin to the

Bentons, one knows this family is blessed with a love for beauty as

found in America, in the dreams of those who sought safety and

Democracy within our shores. May the Quest of those who look for such

fair wonders, never end.

Jon Presco

Copyright 2003

“Almost entirely self-taught – and nearly always painting in

solitude out of fear of criticism – Chrsitne used photographs and

family snapshots as resources from the very beginning.”

The most mimicked image in the world (Mime Mundi) is THE ROSE. I wrote this twenty years ago;

“After God made the world, He began to make His rose, but, left it undone for His Man to finish so he can present it to the Woman he loves.”

Man and woman kind have made many species of the rose, but, is there an archetypal rose?

Above we see the beautiful women of Philip Boileau “The painter of fair women”. He is my kin, he the son of Susan Benton and Baron Boileau. Next to Boileau’s women, are the women of the artist Sara Moon, who is a man who mimicked the rosy images of my late sister, Christine Rosamond Benton. Sara’s woman with scarf looks like my mother, Rosemary Rosamond, who is kin to Baron Boileau who owned a fabulous art collection that was gather in the wake of Napoleon’s conquests. Rosemary’s son-in-law is Garth Benton, a muralist and cousin to the artist, Thomas Hart Benton. Is Rosemary the archetypal rose? No! But, her mother, Mary Magdalene Rosamond, is! You can not own a more archetypal rose name, other then Mary Rose of the World ‘Mother of God and Lord Jesus Creator of the World and Universe’!

One can conclude God made Mary perfect so He could come to earth and be a mortal – for just a little while! Because we mortals did not recognize Jesus as an immortal, we tortured God and put a wreath of thorns upon His head, and thus He is sometimes called ‘The Rose of Sharon’.

Having a blueprint of perfection, all of humanity is bid to BE LIKE JESUS, but too much like Jesus! There can only be ONE JESUS! All imitators will be tied to a stake and burned alive! NO MIMES – PLEASE!

Although Elizabeth was raised a Christian Scientist, she converted to Judaism at Hollywood’s Temple Israel on March 27, 1959. Although she wanted to convert to the Jewish faith while Mike Todd was alive, her desire to do so reached a fever pitch after his tragic death. Elizabeth wrote: “Now, in my steady, gnawing grief for Mike, I felt a desperate need for a formalized religion. I had discovered that I had no way of expressing myself in prayer other than an almost wordless howl to God—’Oh, God, oh God, oh God.’ I wanted something more channeled, more profound, more satisfying.” Elizabeth said she had always felt a connection towards the Jewish faith. “I felt terribly sorry for the suffering of the Jews during the war. I was attracted to their heritage. I guess I identified with them as underdogs.” According to Elizabeth, she “studied for about nine months, went to the temple regularly and converted.” Elizabeth’s Hebrew name is Elisheba Rachel. Elizabeth has always been very proud of her adopted faith—finding great comfort and peace in her adopted religion.

The Call of Gold (1936) by Newell D. Chamberlain

——————————————————————————–

CHAPTER XXVIII

FREMONT’S LATER CAREER

Through the formation of the Wall Street corporation, Fremont realized at least two million dollars. Had the Company not been wrecked within such a short time, he would have made even more.

After the Civil War, he devoted his time and fortune to the promotion of overland transportation. He laid the foundation of the Kansas and Pacific Railroad, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, and the Memphis and Pacific Railroad, in the last of which, through the misconduct of French agents in Paris, his fortune was really lost.

While promoting railroads, he and his family lived luxuriously. He had been so greatly benefited by the stock-selling scheme of the Mariposa Company that he thought he could be successful in promoting stock to build railroads. Being only a visionary dreamer, however, with no practical experience in corporate financing, he became an easy mark for shrewd schemers.

His Memphis and El Paso Railroad had been chartered by the State of Texas and given 18,000,000 acres of land, on the strength of which, bonds were floated. Several millions of dollars worth of these bonds were sold in France, but the agents and banking house kept forty per cent, leaving but sixty per cent for the building of the proposed railroad.

In 1870, the Company became insolvent and Fremont and many of his friends lost everything, to say nothing of the losses sustained by thousands who had purchased stock on the glittering representations of agents. Fremont’s inside knowledge as to the condition of the Company gave him advance information of the impending failure and he could have used that knowledge to save a part of his fortune, had he been dishonest.

The following article appeared in the Mariposa Gazette of April 17, 1874:

“Fremont’s brother-in-law, Baron Boileau, who was sentenced to imprisonment by a Memphis and El Paso R. R. affair, is confined in the conciergerie in Paris. Mme. Boileau and her six children were at last accounts at Boulogne, dependent on the generosity of friends.

“Nine or ten years ago, Baron Boileau was the French consul at New York City, trusted, respected, popular and accomplished. While there, he married Susan, daughter of Colonel Thomas H. Benton, who served thirty years in the United States Senate and who was long the political autocrat of Missouri. The marriage was happy. After his union with Miss Benton, Baron Boileau was appointed French minister to Ecuador, but certain acts of his while Consul at New York were brought to the notice of the government and led to his recall from Ecuador and his discharge from his country’s service.

“While in New York, he became involved in railroad schemes and was induced to recommend, in his capacity as an official agent of the French government, the negotiation of the Memphis and El Paso Railroad bonds. It was for this plain violation of the country’s law, that his government, rigid in such matters, recalled, discharged, fined, imprisoned, in short, ruined him.

“The same Court, which tried him, found General Fremont guilty of raising money on the Memphis and El Paso R. R. bonds, by false representations and sentenced him to serve a year in prison. He made good his escape from France and is beyond the reach of the French Government, it being a strange fact, that although France and America upheld a common cause and fought side by side on fields of battle, they have with each other no extradition treaty.

“Mrs. Fremont was the favorite daughter of Colonel Benton, a woman of rare accomplishments and great ambition. Her hopes have withered; she beholds, as the result of an unfortunate speculation, her husband, who once almost grasped the highest prize in this country’s gift, declared a felon by a friendly Republic and the devoted companion of her sister, hurled from a high pinnacle into ruin and disgrace. How marvelous and melancholy are some of time’s mutations?”

It was later proven that Fremont was not guilty of misrepresentation in the sale of bonds in France. That he acted with absolute honesty but with a lamentable shortness of business judgment, was proven by a letter sent him by the unfriendly Receiver of the defunct company, which read as follows: “I deem it fair that throughout the long and careful scrutiny which I have made into the affairs of the company, I have found no proof that would sustain the charges brought against you, regarding the fraudulent sale of the company’s bonds in France.”

Fremont had proven a dismal failure as a business man and had wrecked many of his friends and relatives.

In 1878, he was appointed Governor of Arizona Territory, by President Hayes, and served four years, at a salary of $2000 a year. On his way out to assume his duties, he visited San Francisco and was given a reception by the Society of California Pioneers.