I believe I recorded a news item that said Waltz and Rubio were in Saudi Arabia during the attack on the Houthi. Rubio said he was included in the Signal chain. I am investigating.

I watched the movie Executive Suite last night starring William Holden. Does Trump love this movie, and, sees himself as…..The Savior of World Companies? Is this why Trump put Elm Musk in all our business? Is there a Huge Corporate Takerover going down? The person who could best answer this question, is Jeffrey Goldstein, who may know Arthur Jensen’s speech in the movie Network by heart.Im going to ask him for an interview. Um going to ask him if he has a theory as to how Jeffrey Goldberg got insluced in a Top Secret War Room chit-chat.

My theory is a secret oil deal is going down, and a big world banker guy is needed to hold THE BIG BAG. Think Poker Game Casino. This is very High Stakes. There are terrorist getting in the way of Big Oil Business. The Houthi are hitting oil tankers taking Saudi Oil to all parts of the globe. Whoever gets rid of the Houthi will be sitting pretty when it comes to Winning The Big Deal.

You want to show investors and The World Bankers, you are the man for the job. You hold a Board Meeting (A War Chit-chat Group) and INVITE SPECTATORS to an attack on the Houthi p for the sake of THE PRINCE. This is why there is discussion about Saudi Arabia where Kurshner went to. The concern is looking hypocritical after ABANDONING Ukraine and Europe.Where was Marco Rubio during the attack?

Why attack the Houthi on THAT DAY? Did Rubio set up a…..WAR CHAT with the billionaire Oil Sheiks, who want assurance the U.S. will make war against the Houthi – as long as it takes? Wouldnt World Banks – want the same assurance? Does the EU have their loyal bankers? Do they see a

HOSTILE TAKEOVER?

Trump os playing a game of Risk – for real! Every World Dictator wants to conquer Europe.

WAKE UP!

They know the Democrats are Allies of NATO Countries. They – just destroyed the Democrats with the help of…..THE PRINC:EY FAMI:Y! How many f them were on THE LIST! Who suggested Jeffrey Godstein be on….THE LIST!

I am going to destroy Vance’s Hillbilly Rights to World Domination bullshit! Greenland just threw his wife out!

John Presco

President: Royal Rosamond Press

Secretary of State Marco Rubio weighed in Wednesday on the ongoing firestorm surrounding a Signal group chat in which Trump officials inadvertently included a journalist while discussing highly sensitive military plans.

The Context

Rubio’s comments came after The Atlantic‘s editor-in-chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, reported that national security adviser Mike Waltz accidentally added him to the Signal group in March, as officials spent several days debating whether to launch military strikes against Houthi targets in Yemen.

The United States has designated the Houthis a foreign terrorist organization. The militant group has been launching attacks on Western commercial vessels in the Red Sea for more than a year.

(L-R) U.S. National Security Advisor Mike Waltz, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan and National Security Advisor Mosaad bin Mohammad al-Aiban, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha, Ukrainian Head of Presidential Office Andriy Yermak and Ukrainian Minister of Defense Rustem Umerovto attend a meeting between the US and Ukraine hosted by the Saudis on March 11, 2025 in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. An American delegation led by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio is in Jeddah to attend a high-stakes meeting with Ukrainian officials, in efforts to lay the groundwork for peace negations to end Russia’s war in Ukraine. The talks come after Zelensky met with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on Monday, and in the wake of a recent rift in US-Ukraine relations.

The group chat had top national security and Cabinet-level officials, including Rubio, Waltz, Vice President JD Vance, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard, CIA director John Ratcliffe and others.

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development.[6] The World Bank is the collective name for the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and International Development Association (IDA), two of five international organizations owned by the World Bank Group. It was established along with the International Monetary Fund at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference. After a slow start, its first loan was to France in 1947. In its early years, it primarily focused on rebuilding Europe.[7] Over time, it focused on providing loans to developing world countries.[8] In the 1970s, the World Bank re-conceptualized its mission of facilitating development as being oriented around poverty reduction.[8] For the last 30 years, it has included NGOs and environmental groups in its loan portfolio. Its loan strategy is influenced by environmental and social safeguards.

As of 2022, the World Bank is run by a president and 25 executive directors, as well as 29 various vice presidents. IBRD and IDA have 189 and 175 member countries, respectively. The U.S., Japan, China, Germany and the U.K. have the most voting power. The bank aims loans at developing countries to help reduce poverty. The bank is engaged in several global partnerships and initiatives, and takes a role in working toward addressing climate change. The World Bank hosts an Open Knowledge Repository for its publications.

In 2020, the World Bank’s total commitments amounted to USD 77.1 billion, it had 12,300 full-time staff, and it operated in 145 countries.[5] World Bank projects cover a range of areas from building schools to fighting disease, providing water and electricity, and environmental protection.[5]

Fidelity National Information Services, Inc. (FIS) is an American multinational corporation which offers a wide range of financial products and services. FIS is most known for its development of Financial Technology, or FinTech, and as of Q2 2024 it offers its solutions in two primary segments: Banking Solutions & Capital Market Solutions. Annually, FIS facilitates the movement of roughly $9 trillion through the processing of approximately 75 billion transactions in service to more than 20,000 clients around the globe.[2]

FIS was ranked second in the FinTech Forward 2016 rankings.[3] After acquiring Worldpay for $35 billion in Q3 of 2019, FIS became the largest processing and payments company in the world.[4]

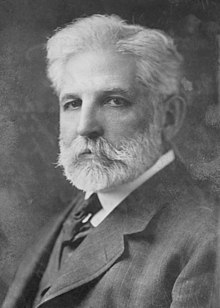

Jeffrey A. Goldstein (born 1955) is a United States economist who was Under Secretary of the Treasury for Domestic Finance from March 27, 2010, to 2011. Jeffrey is currently the chairman of the board of directors of Fidelity National Information Services (FIS).[2]

Biography

[edit]

Jeffrey A. Goldstein, was born on December 2, 1955.[3] He was educated at Vassar College and the London School of Economics,[4] receiving an A.B. in Economics from Vassar in 1977.[3] He then attended graduate school at Yale University, earning an M.A., M.Phil., and a Ph.D. in Economics.[3]

In 1982, Goldstein taught economics at Princeton University.[3] He then worked at the Brookings Institution, focusing his research on international financial policy.[4] Goldstein then joined Wolfensohn & Co., working there for fifteen years.[4] When Wolfensohn & Co. was purchased by Bankers Trust in 1996, Goldstein stayed on as co-chairman of BT Wolfensohn and as a member of Bankers Trust’s management committee.[4]

In 1999, Goldstein became a managing director of the World Bank.[4] He became chief financial officer of the World Bank in 2003, where he was a member of the Management Committee responsible for corporate leadership and strategy. Mr. Goldstein also oversaw the Bank’s work with its client countries in strengthening financial and capital market systems. He helped lead the World Bank’s relationship with the G-8 countries. He served as the Bank’s representative on the Financial Stability Forum and on the IMF’s Capital Markets Consultative Group and chaired the Bank’s Pension Finance Committee. He joined Hellman & Friedman in 2004.[4]

In July 2009, President Barack Obama nominated Goldstein to be Under Secretary of the Treasury for Domestic Finance and he held that office until 2011.[4] In that role, he advised the Secretary on policy issues related to the US banking and financial systems, regulatory reform, financial stability, federal government financing, US housing finance, management of the US Government portfolio of investments in financial institutions and auto companies, fiscal affairs and related economic and financial matters. He was also the Chairman of the Deputies of the Financial Stability Oversight Council and served on the board of the Securities Investor Protection Corporation and was the Board Representative to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.[5]

In July 2011, Secretary of the Treasury Timothy F. Geithner, awarded Goldstein with the Alexander Hamilton award, the highest honor for a presidential appointee.

Mr. Goldstein serves on the board of Bank of New York Mellon, where he is Chairman of the Finance Committee, and sits on the Executive, Compensation, and Risk committees.[6] He also serves as Chairman of the Board of Fidelity National Information Services (FIS),[7] as well as on the boards of Westfield Corporation,[8] Edelman Financial,[8] Vassar College,[8] and Grosvenor Capital Management.[5] He was formerly a Director of LPL Financial, AlixPartners and Arch Capital. He also served on the boards of Save the Children, the International Center for Research on Women, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, the Brookings Institution Global Leadership Council and the London School of Economics North American Advisory Board. Mr. Goldstein was a member and past President of the Board of Trustees of Big Brothers/Big Sisters of New York City. Mr. Goldstein is also a member of the Council on Foreign Relations.[5]

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is an independent and nonpartisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.[3] CFR is based in New York City, with an additional office in Washington, D.C. Its membership has included senior politicians, secretaries of state, CIA directors, bankers, lawyers, professors, corporate directors, CEOs, and prominent media figures.

CFR meetings convene government officials, global business leaders, and prominent members of the intelligence and foreign-policy communities to discuss international issues. CFR publishes the bi-monthly journal Foreign Affairs since 1922. It also runs the David Rockefeller Studies Program, which makes recommendations to presidential administrations and the diplomatic community, testifies before Congress, interacts with the media, and publishes research on foreign policy issues.

Michael Froman is the organization’s 15th president.

Hellman & Friedman LLC (H&F) is an American private equity firm, founded in 1984 by Warren Hellman[2][3] and Tully Friedman, that makes investments primarily through leveraged buyouts as well as growth capital investments. H&F has focused its efforts on several core target industries including media, financial services, professional services and information services. The firm tends to avoid asset intensive or other industrial businesses (e.g., manufacturing, chemicals, transportation). H&F is based in San Francisco, with offices in New York and London.

In June 2024, Hellman & Friedman ranked 13th in Private Equity International‘s PEI 300 ranking among the world’s largest private equity firms.[4]

History

[edit]

| History of private equity and venture capital |

|---|

| Early history |

| (origins of modern private equity) |

| The 1980s |

| (leveraged buyout boom) |

| The 1990s |

| (leveraged buyout and the venture capital bubble) |

| The 2000s |

| (dot-com bubble to the credit crunch) |

| The 2010s |

| (expansion) |

| The 2020s |

| (COVID-19 recession) |

| vte |

Founding

[edit]

Hellman & Friedman was founded in 1984 by Warren Hellman and Tully Friedman. Before H&F, Hellman was a founding partner of Hellman, Ferri Investment Associates, which would later be renamed Matrix Management Company. Today, Matrix is among the most prominent venture capital firms in the U.S. Before that, Hellman worked in investment banking at Lehman Brothers, where he served as president as well as head of the Investment Banking Division and Chairman of Lehman Corporation.[citation needed] Tully Friedman was formerly a managing director at Salomon Brothers. In 1997, Friedman left the firm to found Friedman Fleischer & Lowe, a private equity firm also based in San Francisco.[citation needed]

Recent

[edit]

As of 2011, H&F employed approximately 50 investment professionals, including 15 managing directors, 6 principals and 13 associates as well as senior advisors and general counsels.[citation needed] In August 2013, the firm acquired Canada‘s largest insurance broker, Hub International, for around $4.4 billion.[5] In March 2014, the firm acquired Renaissance Learning, a firm providing assessment methods such as electronic tests that adapt questions in real time depending on how successfully the student is answering, for $1.1 billion in cash.[6]

In February 2015, it was announced that Hellman & Friedman were putting together a takeover bid for used car company Auto Trader, which could amount to an offer of £2 billion.[7] On May 18, 2017, Hellman & Friedman made a A$2.9 billion bid for Fairfax Media in Australia, starting a bidding war with TPG Group for the company.[8]

- Arthur Jensen: You have meddled with the primal forces of nature, Mr. Beale, and I won’t have it! Is that clear? You think you’ve merely stopped a business deal. That is not the case! The Arabs have taken billions of dollars out of this country, and now they must put it back! It is ebb and flow, tidal gravity! It is ecological balance! You are an old man who thinks in terms of nations and peoples. There are no nations. There are no peoples. There are no Russians. There are no Arabs. There are no third worlds. There is no West. There is only one holistic system of systems, one vast and immane, interwoven, interacting, multivariate, multinational dominion of dollars. Petro-dollars, electro-dollars, multi-dollars, reichmarks, rins, rubles, pounds, and shekels. It is the international system of currency which determines the totality of life on this planet. That is the natural order of things today. That is the atomic and subatomic and galactic structure of things today! And YOU have meddled with the primal forces of nature, and YOU… WILL… ATONE! Am I getting through to you, Mr. Beale? You get up on your little twenty-one inch screen and howl about America and democracy. There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM, and ITT, and AT&T, and DuPont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today. What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state, Karl Marx? They get out their linear programming charts, statistical decision theories, minimax solutions, and compute the price-cost probabilities of their transactions and investments, just like we do. We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr. Beale. The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable bylaws of business. The world is a business, Mr. Beale. It has been since man crawled out of the slime. And our children will live, Mr. Beale, to see that… perfect world… in which there’s no war or famine, oppression or brutality. One vast and ecumenical holding company, for whom all men will work to serve a common profit, in which all men will hold a share of stock. All necessities provided, all anxieties tranquilized, all boredom amused. And I have chosen you, Mr. Beale, to preach this evangel.

- Howard Beale: Why me?

- Arthur Jensen: Because you’re on television, dummy. Sixty million people watch you every night of the week, Monday through Friday.

- Howard Beale: I have seen the face of God.

- Arthur Jensen: You just might be right, Mr. Beale.

History

[edit]

Origins, 1918 to 1945

[edit]

In September 1917, near the end of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson established a working fellowship of about 150 scholars called “The Inquiry“, tasked with briefing him about options for the postwar world after Germany was defeated. This academic group, directed by Wilson’s closest adviser and long-time friend “Colonel” Edward M. House, and with Walter Lippmann as Head of Research, met to assemble the strategy for the postwar world.[5]: 13–14 The team produced more than 2,000 documents detailing and analyzing the political, economic, and social facts globally that would be helpful for Wilson in the peace talks. Their reports formed the basis for the Fourteen Points, which outlined Wilson’s strategy for peace after the war’s end. These scholars then traveled to the Paris Peace Conference 1919 and participated in the discussions there.[6]: 1–5

As a result of discussions at the Peace Conference, a small group of British and American diplomats and scholars met on May 30, 1919, at the Hotel Majestic in Paris. They decided to create an Anglo-American organization called “The Institute of International Affairs”, which would have offices in London and New York.[5]: 12 [6]: 5 Ultimately, the British and American delegates formed separate institutes, with the British developing the Royal Institute of International Affairs (known as Chatham House) in London. Due to the isolationist views prevalent in American society at that time, the scholars had difficulty gaining traction with their plan and turned their focus instead to a set of discreet meetings which had been taking place since June 1918 in New York City, under the name “Council on Foreign Relations”. The meetings were headed by corporate lawyer Elihu Root, who had served as Secretary of State under President Theodore Roosevelt, and attended by 108 “high-ranking officers of banking, manufacturing, trading and finance companies, together with many lawyers”.

The members were proponents of Wilson’s internationalism, but they were particularly concerned about “the effect that the war and the treaty of peace might have on postwar business”.[6]: 6–7 The scholars from the inquiry saw an opportunity to create an organization that brought diplomats, high-level government officials, and academics together with lawyers, bankers, and industrialists to influence government policy. On July 29, 1921, they filed a certification of incorporation, officially forming the Council on Foreign Relations.[6]: 8–9 Founding members included its first honorary president, Elihu Root, and first elected president, John W. Davis, vice-president Paul D. Cravath, and secretary–treasurer Edwin F. Gay.[7][4]

In 1922, Gay, who was a former dean of the Harvard Business School and director of the Shipping Board during the war, headed the Council’s efforts to begin publication of a magazine that would be the “authoritative” source on foreign policy. He gathered US$125,000 (equivalent to $2,348,161 in 2024) from the wealthy members on the council, as well as by sending letters soliciting funds to “the thousand richest Americans”. Using these funds, the first issue of Foreign Affairs was published in September 1922. Within a few years, it had gained a reputation as the “most authoritative American review dealing with international relations”.[5]: 17–18

In the late 1930s, the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Foundation began financially supporting the Council.[8] In 1938, they created various Committees on Foreign Relations, which later became governed by the American Committees on Foreign Relations in Washington, D.C., throughout the country, funded by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation. Influential men were to be chosen in a number of cities, and would then be brought together for discussions in their own communities as well as participating in an annual conference in New York. These local committees served to influence local leaders and shape public opinion to build support for the Council’s policies, while also acting as “useful listening posts” through which the Council and U.S. government could “sense the mood of the country”.[5]: 30–31

During the Second World War, the Council achieved much greater prominence within the government and the State Department, when it established the strictly confidential War and Peace Studies, funded entirely by the Rockefeller Foundation.[6]: 23 The secrecy surrounding this group was such that the Council members who were not involved in its deliberations were completely unaware of the study group’s existence.[6]: 26 It was divided into four functional topic groups: economic and financial; security and armaments; territorial; and political. The security and armaments group was headed by Allen Welsh Dulles, who later became a pivotal figure in the CIA‘s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). CFR ultimately produced 682 memoranda for the State Department, which were marked classified and circulated among the appropriate government departments•[6]: 23–26

Cold War era, 1945 to 1979

[edit]

A critical study found that of 502 government officials surveyed from 1945 to 1972, more than half were members of the Council.[6]: 48 During the Eisenhower administration 40% of the top U.S. foreign policy officials were CFR members (Eisenhower himself had been a council member); under Truman, 42% of the top posts were filled by council members. During the Kennedy administration, this number rose to 51%, and peaked at 57% under the Johnson administration.[5]: 62–64

In an anonymous piece called “The Sources of Soviet Conduct” that appeared in Foreign Affairs in 1947, CFR study group member George Kennan coined the term “containment“. The essay would prove to be highly influential in US foreign policy for seven upcoming presidential administrations. Forty years later, Kennan explained that he had never suspected the Russians of any desire to launch an attack on America; he thought that it was obvious enough and he did not need to explain it in his essay. William Bundy credited CFR’s study groups with helping to lay the framework of thinking that led to the Marshall Plan and NATO. Due to new interest in the group, membership grew towards 1,000.[6]: 35–39

Dwight D. Eisenhower chaired a CFR study group while he served as President of Columbia University. One member later said, “whatever General Eisenhower knows about economics, he has learned at the study group meetings.”[6]: 35–44 The CFR study group devised an expanded study group called “Americans for Eisenhower” to increase his chances for the presidency. Eisenhower would later draw many Cabinet members from CFR ranks and become a CFR member himself. His primary CFR appointment was Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. Dulles gave a public address at the Harold Pratt House in New York City in which he announced a new direction for Eisenhower’s foreign policy: “There is no local defense which alone will contain the mighty land power of the communist world. Local defenses must be reinforced by the further deterrent of massive retaliatory power.” After this speech, the council convened a session on “Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy” and chose Henry Kissinger to head it. Kissinger spent the following academic year working on the project at Council headquarters. The book of the same name that he published from his research in 1957 gave him national recognition, topping the national bestseller lists.[6]: 39–41

CFR played an important role in the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community.[9] CFR promoted a blueprint of the ECSC and helped Jean Monnet promote the ESCS.[9]

On November 24, 1953, a study group heard a report from political scientist William Henderson regarding the ongoing conflict between France and Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh‘s Viet Minh forces, a struggle that would later become known as the First Indochina War. Henderson argued that Ho’s cause was primarily nationalist in nature and that Marxism had “little to do with the current revolution.” Further, the report said, the United States could work with Ho to guide his movement away from Communism. State Department officials, however, expressed skepticism about direct American intervention in Vietnam and the idea was tabled. Over the next twenty years, the United States would find itself allied with anti-Communist South Vietnam and against Ho and his supporters in the Vietnam War.[6]: 40, 49–67

The Council served as a “breeding ground” for important American policies such as mutual deterrence, arms control, and nuclear non-proliferation.[6]: 40–42

In 1962 the group began a program of bringing select Air Force officers to the Harold Pratt House to study alongside its scholars. The Army, Navy and Marine Corps requested they start similar programs for their own officers.[6]: 46

A four-year-long study of relations between America and China was conducted by the Council between 1964 and 1968. One study published in 1966 concluded that American citizens were more open to talks with China than their elected leaders. Henry Kissinger had continued to publish in Foreign Affairs and was appointed by President Richard Nixon to serve as National Security Adviser in 1969. In 1971, he embarked on a secret trip to Beijing to broach talks with Chinese leaders. Nixon went to China in 1972, and diplomatic relations were completely normalized by President Carter‘s Secretary of State, another Council member, Cyrus Vance.[6]: 42–44

The Vietnam War created a rift within the organization. When Hamilton Fish Armstrong announced in 1970 that he would be leaving the helm of Foreign Affairs after 45 years, new chairman David Rockefeller approached a family friend, William Bundy, to take over the position. Anti-war advocates within the Council rose in protest against this appointment, claiming that Bundy’s hawkish record in the State and Defense Departments and the CIA precluded him from taking over an independent journal. Some considered Bundy a war criminal for his prior actions.[6]: 50–51

In November 1979, while chairman of CFR, David Rockefeller became embroiled in an international incident when he and Henry Kissinger, along with John J. McCloy and Rockefeller aides, persuaded President Jimmy Carter through the State Department to admit the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, into the US for hospital treatment for lymphoma. This action directly precipitated what is known as the Iran hostage crisis and placed Rockefeller under intense media scrutiny (particularly from The New York Times) for the first time in his public life.[10][11]

In his book, White House Diary, Carter wrote of the affair, “April 9 [1979] David Rockefeller came in, apparently to induce me to let the shah come to the United States. Rockefeller, Kissinger, and Brzezinski seem to be adopting this as a joint project”.[12]

Membership

[edit]

Main article: Members of the Council on Foreign Relations

The CFR has two types of membership: life membership; and term membership, which lasts for 5 years and is available only to those between the ages of 30 and 36. Only U.S. citizens (native born or naturalized) and permanent residents who have applied for U.S. citizenship are eligible. A candidate for life membership must be nominated in writing by one Council member and seconded by a minimum of three others. Visiting fellows are prohibited from applying for membership until they have completed their fellowship tenure.[13]

Corporate membership is divided into “Associates”, “Affiliates”, “President’s Circle”, and “Founders”. All corporate executive members have opportunities to hear speakers, including foreign heads of state, chairmen and CEOs of multinational corporations, and U.S. officials and Congressmen. President and premium members are also entitled to attend small, private dinners or receptions with senior American officials and world leaders.[14]

The CFR has a Young Professionals Briefing Series designed for young leaders interested in international relations to be eligible for term membership.[15]

Women were excluded from membership until the 1960s.[16]

Board members

[edit]

As of 2024, members of CFR’s board of directors include:[17]

- David M. Rubenstein (chairman) – cofounder and co-chief executive officer, The Carlyle Group, regent of the Smithsonian Institution, chairman of the board for Duke University, co-chair of the board at the Brookings Institution, president of the Economic Club of Washington, and owner of the Baltimore Orioles.

- Blair Effron (vice chairman) – cofounder, Centerview Partners

- Jami Miscik (vice chairman) – senior advisor at Lazard Geopolitical Advisory and chief executive officer of Global Strategic Insights; former chief executive officer and vice chairman, Kissinger Associates, Inc. Ms. Miscik served as the global head of sovereign risk at Lehman Brothers. She also serves as a senior advisor to Barclays Capital

- Michael Froman (president) – former vice chairman and president, strategic growth, at Mastercard; former U.S. trade representative (2013–2017) under President Barack Obama

- Nicholas F. Beim − partner at Venrock

- Afsaneh Mashayekhi Beschloss − founder and chief executive officer, RockCreek

- Margaret Brennan − moderator, Face the Nation; chief foreign affairs correspondent, CBS News

- Sylvia Mathews Burwell – president, American University; former United States Secretary of Health and Human Services (2014–2017) under President Barack Obama

- Kenneth I. Chenault − chairman and managing director, General Catalyst

- Tony Coles − executive chairman, Cerevel Therapeutics; co-founder and co-chair for the Black Economic Alliance

- Cesar Conde – chairman, NBCUniversal News Group

- Michèle Flournoy – cofounder and managing partner, WestExec Advisors; cofounder, former chief executive officer, and now chair of the Center for a New American Security (CNAS)

- Jane Fraser – chief executive officer, Citi

- Stephen Freidheim – chief investment officer, founder, managing partner, Cyrus Capital Partners L.P.

- James P. Gorman – executive chairman, Morgan Stanley

- Stephen Hadley – principal at Rice, Hadley, Gates, and Manuel; he was the 21st National Security Advisor

- Margaret (Peggy) Hamburg − former US FDA commissioner; former foreign secretary, National Academy of Medicine

- William Hurd − former U.S. representative for Texas’s 23rd congressional district (2015−2021); former CIA clandestine officer

- Charles R. Kaye − chief executive officer, Warburg Pincus

- James Manyika − senior vice president, head of technology and society, Google; senior partner emeritus and chair emeritus of the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI)

- Laurene Powell Jobs – founder and president, Emerson Collective

- William H. McRaven – professor of national security, Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin

- Justin Muzinich – chief executive officer, Muzinich & Company; former U.S. Deputy Secretary of the Treasury (2018–2021)

- Janet Napolitano – professor of public policy, Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley, former U.S. Attorney (1993–1997), Attorney General of Arizona (1999–2003), Governor of Arizona (2003–2009), and President Barack Obama‘s first Homeland Security Secretary (2009–2013)

- Meghan L. O’Sullivan − director of Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor of the Practice of International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School

- Deven J. Parekh – managing director, Insight Partners

- Charles Phillips − managing partner and cofounder, Recognize

- Richard L. Plepler – founder and chief executive officer, Eden Productions

- Ruth Porat – president, chief investment officer, and chief financial officer, Alphabet and Google

- L. Rafael Reif – president emeritus, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Mariko Silver – president and chief executive officer, The Henry Luce Foundation; former president, Bennington College

- James D. Taiclet – chairman, president, and chief executive officer, Lockheed Martin; associate fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Frances Fragos Townsend − executive vice president of corporate affairs, corporate secretary, chief compliance officer, Activision Blizzard

- Tracey T. Travis – executive vice president of finance and chief financial officer, Estée Lauder Companies

- Fareed Zakaria – host, CNN’s Fareed Zakaria GPS; columnist for the Washington Post, contributing editor for the Atlantic; former managing editor of Foreign Affairs (1992–2000)

- Amy Zegart – Morris Arnold and Nona Jean Cox senior fellow at the Hoover Institution; professor of political science by courtesy at Stanford University

- Jon F. Weber – Investor, corporate restructuring specialist, and former executive at Icahn Enterprises, Elliott Investment Management, and Goldman Sachs Special Situations Group.

As a charity

[edit]

The Council on Foreign Relations received a three-star rating (out of four stars) from Charity Navigator in fiscal year 2016, as measured by an analysis of the council’s financial data and “accountability and transparency”.[18] In fiscal year 2023, the council received a four-star rating (98 percent) from Charity Navigator.[19]

Reception

[edit]

In an article for The Washington Post, Richard Harwood described the membership of the CFR as “the nearest thing we have to a ruling establishment in the United States”.[20]

The CFR has been criticized for its perceived elitism and influence over U.S. foreign policy, with detractors arguing that it serves as a networking hub for government officials, corporate executives, and media figures, reinforcing an establishment consensus that prioritizes globalist policies over national interests.[21][22][23]

In 2019, CFR was criticized for accepting a donation from Len Blavatnik, a Ukrainian-born billionaire with close links to Vladimir Putin.[24] The council was reported to be under fire from its own members and dozens of international affairs experts over its acceptance of a $12 million gift to fund an internship program.[25] Fifty-five international relations scholars and Russia experts wrote a letter to the organization’s board and CFR president Richard N. Haass:

“It is our considered view that Blavatnik uses his ‘philanthropy’—funds obtained by and with the consent of the Kremlin, at the expense of the state budget and the Russian people—at leading western academic and cultural institutions to advance his access to political circles. We regard this as another step in the longstanding effort of Mr. Blavatnik—who … has close ties to the Kremlin and its kleptocratic network—to launder his image in the West.”[26]

Additionally, critics have accused the CFR of promoting interventionist foreign policies, arguing that its reports and recommendations have often supported U.S. military interventions and regime-change efforts. Some opponents claim that its influence contributes to a bipartisan consensus that favors global military engagement, economic neoliberalism, and the interests of multinational corporations.[27][28][29]

Bank of New York

[edit]

The first bank in the U.S. was the Bank of North America in Philadelphia, which was chartered by the Continental Congress in 1781; Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were among its founding shareholders.[8] In February 1784, The Massachusetts Bank in Boston was chartered.[8]

The shipping industry in New York City chafed under the lack of a bank, and investors envied the 14% dividends that Bank of North America paid, and months of local discussion culminated in a June 1784 meeting at a coffee house on St. George’s Square which led to the formation of the Bank of New York company.[citation needed] The bank operated without a charter for seven years.[9] The initial plan was to capitalize the company with $750,000, a third in cash and the rest in mortgages, but after this was disputed the first offering was to capitalize it with $500,000 in gold or silver. When the bank opened on June 9, 1784, the full $500,000 had not been raised; 723 shares had been sold, held by 192 people. Aaron Burr had three of them, and Hamilton had one and a half shares. The first president was Alexander McDougall and the Cashier was William Seton.[10][11][12][13]

Its first offices were in the old Walton Mansion in New York City.[3][10][11] In 1787, it moved to a site on Hanover Square that the New York Cotton Exchange later moved into.[10]

The bank provided the United States government its first loan in 1789. The loan was orchestrated by Hamilton, then Secretary of the Treasury, and it paid the salaries of United States Congress members and President George Washington.[14]

The Bank of New York was the first company to be traded on the New York Stock Exchange when it first opened in 1792.[15] In 1796, the bank moved to a location at the corner of Wall Street and William Street, which would later become 48 Wall Street.[10][16]

The bank had a monopoly on banking services in the city until the Bank of the Manhattan Company was founded by Aaron Burr in 1799; the Bank of New York and Hamilton vigorously opposed its founding.[10]

During the 19th century, the bank was known for its conservative lending practices that allowed it to weather financial crises. It was involved in the funding of the Morris and Erie canals, and steamboat companies.[17][18] The bank helped finance both the War of 1812 and the Union Army during the American Civil War.[19][20] Following the Civil War, the bank loaned money to many major infrastructure projects, including utilities, railroads, and the New York City Subway.[17]

Standard Oil is the common name for a corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founded in 1870 by John D. Rockefeller. The trust was born on January 2, 1882, when a group of 41 investors signed the Standard Oil Trust Agreement, which pooled their securities of 40 companies into a single holding agency managed by nine trustees.[6] The original trust was valued at $70 million. On March 21, 1892, the Standard Oil Trust was dissolved and its holdings were reorganized into 20 independent companies that formed an unofficial union referred to as “Standard Oil Interests.”[7] In 1899, the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) acquired the shares of the other 19 companies and became the holding company for the trust.[8]

Jersey Standard operated a near monopoly in the American oil industry from 1899 until 1911 and was the largest corporation in the United States. In 1911, the landmark Supreme Court case Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States found Jersey Standard guilty of anticompetitive practices and ordered it to break up its holdings. The charge against Jersey came about in part as a consequence of the reporting of Ida Tarbell, who wrote The History of the Standard Oil Company.[9] The net value of companies severed from Jersey Standard in 1911 was $375 million, which constituted 57 per cent of Jersey’s value. After the dissolution, Jersey Standard became the United States’ second largest corporation after United States Steel.[10]

The Standard Oil Company (New Jersey), which was renamed Exxon in 1973 and ExxonMobil in 1999, remains one of the largest public oil companies in the world. Many of the companies disassociated from Jersey Standard in 1911 remained powerful businesses through the twentieth century. These included the Standard Oil Company of New York, Standard Oil Company (Indiana), Standard Oil Company (California), Ohio Oil Company, Continental Oil Company, and Atlantic Refining Company.

Founding and early years

[edit]

Standard Oil’s prehistory began in 1863, as an Ohio partnership formed by industrialist John D. Rockefeller, his brother William Rockefeller, Henry Flagler, chemist Samuel Andrews, silent partner Stephen V. Harkness, and Oliver Burr Jennings, who had married the sister of William Rockefeller’s wife.[11] In 1870, Rockefeller abolished the partnership and incorporated Standard Oil in Ohio. The company was established with $1 million in capital.[11] Of the initial 10,000 shares, John D. Rockefeller received 2,667, Harkness received 1,334, William Rockefeller, Flagler, and Andrews received 1,333 each, Jennings received 1,000, and the firm of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler received 1,000.[12] Rockefeller chose the “Standard Oil” name as a symbol of the reliable “standards” of quality and service that he envisioned for the nascent oil industry.[13]

In the early years, John D. Rockefeller dominated the combine; he was the single most important figure in shaping the new oil industry.[15] He quickly distributed power and the tasks of policy formation to a system of committees, but always remained the largest shareholder. Authority was centralized in the company’s main office in Cleveland, but decisions in the office were made cooperatively.[16]

The company grew by increasing sales and through acquisitions. After purchasing competing firms, Rockefeller shut down those he believed to be inefficient and kept the others. In a seminal deal, in 1868, the Lake Shore Railroad, a part of the New York Central, gave Rockefeller’s firm a going rate of one cent a gallon or forty-two cents a barrel, an effective 71% discount from its listed rates in return for a promise to ship at least 60 carloads of oil daily and to handle loading and unloading on its own.[17] Smaller companies decried such deals as unfair because they were not producing enough oil to qualify for discounts.

Standard’s actions and secret transport deals helped its kerosene price to drop from 58 to 26 cents from 1865 to 1870.[18] Rockefeller used the Erie Canal as a cheap alternative form of transportation—in the summer months when it was not frozen—to ship his refined oil from Cleveland to the industrialized Northeast. In the winter months, his only options were the three trunk lines—the Erie Railroad and the New York Central Railroad to New York City, and the Pennsylvania Railroad to Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.[19]

Competitors disliked the company’s business practices, but consumers liked the lower prices. Standard Oil, being formed well before the discovery of the Spindletop oil field (in Texas, far from Standard Oil’s base in the Midwest) and a demand for oil other than for heat and light, was well placed to control the growth of the oil business. The company was perceived to own and control all aspects of the trade.

South Improvement Company

[edit]

In 1872, Rockefeller joined the South Improvement Co. which would have allowed him to receive rebates for shipping and drawbacks on oil his competitors shipped. He successfully convinced refineries in Cleveland to sell their businesses to Standard Oil in exchange for cash or stock.[20] But when this deal became known, competitors convinced the Pennsylvania Legislature to revoke South Improvement’s charter. No oil was ever shipped under this arrangement.[21] Using highly effective tactics, later widely criticized, it absorbed or destroyed most of its competition in Cleveland in less than two months[how?] and later throughout the northeastern United States.

Hepburn Committee

[edit]

A. Barton Hepburn was directed by the New York State Legislature in 1879, to investigate the railroads’ practice of giving rebates to their largest clients within the state.[22] Merchants without ties to the oil industry had pressed for the hearings. Prior to the committee’s investigation, few knew of the size of Standard Oil’s control and influence on seemingly unaffiliated oil refineries and pipelines—Hawke (1980) cites that only a dozen or so within Standard Oil knew the extent of company operations.[23]

The committee counsel, Simon Sterne, questioned representatives from the Erie Railroad and the New York Central Railroad and discovered that at least half of their long-haul traffic granted rebates and much of this traffic came from Standard Oil. Even independent companies not allied with Standard Oil confirmed receiving these rebates such as Simon Bernheimner, who was once a partner of the Olefin Oil Company.[24] The committee then shifted its focus to Standard Oil’s operations. John Dustin Archbold, as president of Acme Oil Company, denied that Acme was associated with Standard Oil. He then admitted to being a director of Standard Oil.[23]

The committee’s final report scolded the railroads for their rebate policies and cited Standard Oil as an example. This scolding was largely moot to Standard Oil’s interests since long-distance oil pipelines were now their preferred method of transportation.[23]

Standard Oil Trust

[edit]

In response to state laws that had the result of limiting the scale of companies, Rockefeller and his associates developed innovative ways of organizing to effectively manage their fast-growing enterprise. On January 2, 1882,[25] they combined their disparate companies, spread across dozens of states, under a single group of trustees. By a secret agreement, the existing 37 stockholders conveyed their shares “in trust” to nine trustees:[26] John and William Rockefeller, Oliver H. Payne, Charles Pratt, Henry Flagler, John D. Archbold, William G. Warden, Jabez Bostwick, and Benjamin Brewster.[27]

“Whereas some state legislatures imposed special taxes on out-of-state corporations doing business in their states, other legislatures forbade corporations in their state from holding the stock of companies based elsewhere. (Legislators established such restrictions in the hope that they would force successful companies to incorporate—and thus pay taxes—in their state.)” [28][29] Standard Oil’s organizational concept proved so successful that other giant enterprises adopted this “trust” form.

By 1882, Rockefeller’s top aide was John Dustin Archbold, whom he left in control after disengaging from business to concentrate on philanthropy after 1896. Other notable principals of the company include Henry Flagler, developer of the Florida East Coast Railway and resort cities, and Henry H. Rogers, who built the Virginian Railway.

In 1885, Standard Oil of Ohio moved its headquarters from Cleveland to its permanent headquarters at 26 Broadway in New York City. Concurrently, the trustees of Standard Oil of Ohio chartered the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey (SOCNJ) to take advantage of New Jersey’s more lenient corporate stock ownership laws.

Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890

[edit]

In 1890, Congress overwhelmingly passed the Sherman Antitrust Act (Senate 51–1; House 242–0), a source of American anti-monopoly laws. The law forbade every contract, scheme, deal, or conspiracy to restrain trade, though the phrase “restraint of trade” remained subjective. The Standard Oil group quickly attracted attention from antitrust authorities leading to a lawsuit filed by Ohio Attorney General David K. Watson.

Earnings and dividends

[edit]

From 1882 to 1906, Standard paid out $548,436,000 (equivalent to $13,941,200,000 in 2023) in dividends at a 65.4% payout ratio. The total net earnings from 1882 to 1906 amounted to $838,783,800 (equivalent to $21,321,800,000 in 2023), exceeding the dividends by $290,347,800, which was used for plant expansions.

1895–1913

[edit]

In 1896, John Rockefeller retired from the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey, the holding company of the group, but remained president and a major shareholder. Vice-president John Dustin Archbold took a large part in the running of the firm. In the year 1904, Standard Oil controlled 91% of oil refinement and 85% of final sales in the United States.[31] At this time, state and federal laws sought to counter this development with antitrust laws. In 1911, the U.S. Justice Department sued the group under the federal antitrust law and ordered its breakup into 39 companies.

Standard Oil’s market position was initially established through an emphasis on efficiency and responsibility. While most companies dumped gasoline in rivers (this was before the automobile was popular), Standard used it to fuel its machines. While other companies’ refineries piled mountains of heavy waste, Rockefeller found ways to sell it. For example, Standard bought the company that invented and produced Vaseline, the Chesebrough Manufacturing Co., which was a Standard company only from 1908 until 1911.

One of the original “Muckrakers” Ida M. Tarbell, was an American author and journalist whose father was an oil producer whose business had failed because of Rockefeller’s business dealings. After extensive interviews with a sympathetic senior executive of Standard Oil, Henry H. Rogers, Tarbell’s investigations of Standard Oil fueled growing public attacks on Standard Oil and monopolies in general. Her work was published in 19 parts in McClure’s magazine from November 1902 to October 1904, then in 1904 as the book The History of the Standard Oil Co.

The Standard Oil Trust was controlled by a small group of families. Rockefeller stated in 1910: “I think it is true that the Pratt family, the Payne–Whitney family (which were one, as all the stock came from Colonel Payne), the Harkness-Flagler family (which came into the company together) and the Rockefeller family controlled a majority of the stock during all the history of the company up to the present time.”[32]

These families reinvested most of the dividends in other industries, especially railroads. They also invested heavily in the gas and the electric lighting business (including the giant Consolidated Gas Co. of New York City). They made large purchases of stock in U.S. Steel, Amalgamated Copper, and even Corn Products Refining Co.[33]

Weetman Pearson, a British petroleum entrepreneur in Mexico, began negotiating with Standard Oil in 1912–13 to sell his “El Aguila” oil company, since Pearson was no longer bound to promises to the Porfirio Díaz regime (1876–1911) to not to sell to U.S. interests. However, the deal fell through and the firm was sold to Royal Dutch Shell.[34]

China

[edit]

Standard Oil’s production increased so rapidly it soon exceeded U.S. demand, and the company began viewing export markets. In the 1890s, Standard Oil began marketing kerosene to China’s large population of close to 400 million as lamp fuel.[35] For its Chinese trademark and brand, Standard Oil adopted the name Mei Foo (Chinese: 美孚) as a transliteration.[36][37] Mei Foo also became the name of the tin lamp that Standard Oil produced and gave away or sold cheaply to Chinese farmers, encouraging them to switch from vegetable oil to kerosene. The response was positive, sales boomed, and China became Standard Oil’s largest market in Asia. Prior to Pearl Harbor, Stanvac was the largest single U.S. investment in Southeast Asia.[38]

The North China Department of Socony (Standard Oil Company of New York) operated a subsidiary called Socony River and Coastal Fleet, North Coast Division, which became the North China Division of Stanvac (Standard Vacuum Oil Company) after that company was formed in 1933.[39] To distribute its products, Standard Oil constructed storage tanks, canneries (bulk oil from large ocean tankers was re-packaged into 5-US-gallon (19 L; 4.2 imp gal) tins), warehouses, and offices in key Chinese cities. For inland distribution, the company had motor tank trucks and railway tank cars, and for river navigation, it had a fleet of low-draft steamers and other vessels.[40]

Stanvac’s North China Division, based in Shanghai, owned hundreds of vessels, including motor barges, steamers, launches, tugboats, and tankers.[41] Up to 13 tankers operated on the Yangtze River, the largest of which were Mei Ping (1,118 gross register tons (GRT)), Mei Hsia (1,048 GRT), and Mei An (934 GRT).[42] All three were destroyed in the 1937 USS Panay incident.[43]

Mei An was launched in 1901 and was the first vessel in the fleet. Other vessels included Mei Chuen, Mei Foo, Mei Hung, Mei Kiang, Mei Lu, Mei Tan, Mei Su, Mei Hsia, Mei Ying, and Mei Yun. Mei Hsia, a tanker, was specially designed for river duty. It was built by New Engineering and Shipbuilding Works of Shanghai, who also built the 500-ton launch Mei Foo in 1912.[44][45]

Mei Hsia (“Beautiful Gorges”) was launched in 1926 and carried 350 tons of bulk oil in three holds, plus a forward cargo hold, and space between decks for carrying general cargo or packed oil. She had a length of 206 feet (63 m), a beam of 32 feet (9.8 m), a depth of 10 feet 6 inches (3.2 m), and had a bulletproof wheelhouse. Mei Ping (“Beautiful Tranquility”), launched in 1927, was designed off-shore, but assembled and finished in Shanghai. Its oil-fuel burners came from the U.S. and water-tube boilers came from England.[44][45]

Middle East

[edit]

Standard Oil Company and Socony-Vacuum Oil Company became partners in providing markets for the oil reserves in the Middle East. In 1906, SOCONY (later Mobil) opened its first fuel terminals in Alexandria. It explored in Palestine before the World War broke out, but ran into conflict with the local authorities.[46]

Monopoly charges and antitrust legislation

[edit]

See also: Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States

By 1890, Standard Oil controlled 88 percent of the refined oil flows in the United States. The state of Ohio successfully sued Standard, compelling the dissolution of the trust in 1892. But Standard simply separated Standard Oil of Ohio and kept control of it. Eventually, the state of New Jersey changed its incorporation laws to allow a company to hold shares in other companies in any state.[47]

So, in 1899, the Standard Oil Trust, based at 26 Broadway in New York, was legally reborn as a holding company, the Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey (SOCNJ), which held stock in 41 other companies, which controlled other companies, which in turn controlled yet other companies. According to Daniel Yergin in his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (1990), this conglomerate was seen by the public as all-pervasive, controlled by a select group of directors, and completely unaccountable.[47]

In 1904, Standard controlled 91 percent of production and 85 percent of final sales. Most of its output was kerosene, of which 55 percent was exported around the world. After 1900 it did not try to force competitors out of business by selling at a loss.[48] The federal Commissioner of Corporations studied Standard’s operations from the period of 1904 to 1906[49] and concluded that “beyond question … the dominant position of the Standard Oil Co. in the refining industry was due to unfair practices—to abuse of the control of pipe-lines, to railroad discriminations, and to unfair methods of competition in the sale of the refined petroleum products”.[50]

Because of competition from other firms, their market share gradually eroded to 70 percent by 1906 which was the year when the antitrust case was filed against Standard. Standard’s market share was 64 percent by 1911 when Standard was ordered broken up.[51] At least 147 refining companies were competing with Standard including Gulf, Texaco, and Shell.[52] It did not try to monopolize the exploration and extraction of oil (its share in 1911 was 11 percent).[citation needed]

In 1909, the U.S. Justice Department sued Standard under federal antitrust law, the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, for sustaining a monopoly and restraining interstate commerce by:

Rebates, preferences, and other discriminatory practices in favor of the combination by railroad companies; restraint and monopolization by control of pipe lines, and unfair practices against competing pipe lines; contracts with competitors in restraint of trade; unfair methods of competition, such as local price cutting at the points where necessary to suppress competition; [and] espionage of the business of competitors, the operation of bogus independent companies, and payment of rebates on oil, with the like intent.[53]

The lawsuit argued that Standard’s monopolistic practices had taken place over the preceding four years:

The general result of the investigation has been to disclose the existence of numerous and flagrant discriminations by the railroads on behalf of the Standard Oil Co. and its affiliated corporations. With comparatively few exceptions, mainly of other large concerns in California, the Standard has been the sole beneficiary of such discriminations. In almost every section of the country that company has been found to enjoy some unfair advantages over its competitors, and some of these discriminations affect enormous areas.[54]

The government identified four illegal patterns: (1) secret and semi-secret railroad rates; (2) discriminations in the open arrangement of rates; (3) discriminations in classification and rules of shipment; (4) discriminations in the treatment of private tank cars. The government alleged:

Almost everywhere the rates from the shipping points used exclusively, or almost exclusively, by the Standard are relatively lower than the rates from the shipping points of its competitors. Rates have been made low to let the Standard into markets, or they have been made high to keep its competitors out of markets. Trifling differences in distances are made an excuse for large differences in rates favorable to the Standard Oil Co., while large differences in distances are ignored where they are against the Standard. Sometimes connecting roads prorate on oil—that is, make through rates which are lower than the combination of local rates; sometimes they refuse to prorate; but in either case the result of their policy is to favor the Standard Oil Co. Different methods are used in different places and under different conditions, but the net result is that from Maine to California the general arrangement of open rates on petroleum oil is such as to give the Standard an unreasonable advantage over its competitors.[55]

The government said that Standard raised prices to its monopolistic customers but lowered them to hurt competitors, often disguising its illegal actions by using bogus, supposedly independent companies it controlled.

The evidence is, in fact, absolutely conclusive that the Standard Oil Co. charges altogether excessive prices where it meets no competition, and particularly where there is little likelihood of competitors entering the field, and that, on the other hand, where competition is active, it frequently cuts prices to a point which leaves even the Standard little or no profit, and which more often leaves no profit to the competitor, whose costs are ordinarily somewhat higher.[56]

On May 15, 1911, the US Supreme Court upheld the lower court judgment and declared the Standard Oil group to be an “unreasonable” monopoly under the Sherman Antitrust Act, Section II. It ordered Standard to break up into 39 independent companies with different boards of directors, the biggest two of the companies being Standard Oil of New Jersey (which became Exxon) and Standard Oil of New York (which became Mobil).[57]

Standard’s president, John D. Rockefeller, had long since retired from any management role. But, as he owned a quarter of the shares of the resultant companies, and those share values mostly doubled, he emerged from the dissolution as the richest man in the world.[58] The dissolution had actually propelled Rockefeller’s personal wealth.[59]

Breakup

[edit]

Main articles: Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States and Successors of Standard Oil

By 1911 the Supreme Court of the United States ruled, in Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, that Standard Oil of New Jersey must be dissolved under the Sherman Antitrust Act and split into 34 companies.[60][61] Two of these companies were Standard Oil of New Jersey (Jersey Standard or Esso), which eventually became Exxon, and Standard Oil of New York (Socony), which eventually became Mobil; those two companies later merged into ExxonMobil.

Over the next few decades, both companies grew significantly. Jersey Standard, led by Walter C. Teagle, became the largest oil producer in the world. It acquired a 50 percent share in Humble Oil & Refining Co., a Texas oil producer. Socony purchased a 45 percent interest in Magnolia Petroleum Co., a major refiner, marketer, and pipeline transporter. In 1931, Socony merged with Vacuum Oil Co., an industry pioneer dating back to 1866, and a growing Standard Oil spin-off in its own right.[61]

In the Asia-Pacific region, Jersey Standard had oil production and refineries in the Dutch East Indies but no marketing network. Socony-Vacuum had Asian marketing outlets supplied remotely from California. In 1933, Jersey Standard and Socony-Vacuum merged their interests in the region into a 50–50 joint venture. Standard-Vacuum Oil Co., or “Stanvac”, operated in 50 countries, from East Africa to New Zealand, before it was dissolved in 1962.

Rockefeller’s original company, Standard Oil Company of Ohio (Sohio), effectively ceased to exist when it was purchased by BP in 1987.[62] BP continued to sell gasoline under the Sohio brand until 1991.[62] Other Standard oil entities include “Standard Oil of Indiana” which became Amoco after other mergers and a name change in the 1980s, and “Standard Oil of California” which became the Chevron Corp.

Legacy and criticism of breakup

[edit]

This logo used by Amoco (originally Standard Oil of Indiana, today a subsidiary of BP) is often affiliated with Standard Oil

In the western United States, Standard Oil’s successors used a chevron logo, paving the way for Standard Oil of California to rename itself to Chevron Corporation

Some have speculated that if not for that court ruling, Standard Oil could have possibly been worth more than $1 trillion in the 2000s.[63] Whether the breakup of Standard Oil was beneficial is a matter of some controversy.[64] Some economists believe that Standard Oil was not a monopoly, and argue that the intense free market competition resulted in cheaper oil prices and more diverse petroleum products. Critics claimed that success in meeting consumer needs was driving other companies, who were not as successful, out of the market.[65]

An example of this thinking was given in 1890, when Rep. William Mason, arguing in favor of the Sherman Antitrust Act, said: “trusts have made products cheaper, have reduced prices; but if the price of oil, for instance, were reduced to one cent a barrel, it would not right the wrong done to people of this country by the trusts which have destroyed legitimate competition and driven honest men from legitimate business enterprise”.[65]

The Sherman Antitrust Act prohibits the restraint of trade. Defenders of Standard Oil insist that the company did not restrain trade; they were simply superior competitors. The federal courts ruled otherwise.

Some economic historians have observed that Standard Oil was in the process of losing its monopoly at the time of its breakup in 1911. Although Standard had 90 percent of American refining capacity in 1880, by 1911, that had shrunk to between 60 and 65 percent because of the expansion in capacity by competitors.[66] Numerous regional competitors (such as Pure Oil in the East, Texaco and Gulf Oil in the Gulf Coast, Cities Service and Sun in the Midcontinent, Union in California, and Shell overseas) had organized themselves into competitive vertically integrated oil companies, the industry structure pioneered years earlier by Standard itself.[67]

In addition, demand for petroleum products was increasing more rapidly than the ability of Standard to expand. The result was that although in 1911 Standard still controlled most production in the older regions of the Appalachian Basin (78 percent share, down from 92 percent in 1880), Lima-Indiana (90 percent, down from 95 percent in 1906), and the Illinois Basin (83 percent, down from 100 percent in 1906), its share was much lower in the rapidly expanding new regions that would dominate U.S. oil production in the 20th century. In 1911, Standard controlled only 44 percent of production in the Midcontinent, 29 percent in California, and 10 percent on the Gulf Coast.[67]

Some analysts argue that the breakup was beneficial to consumers in the long run, and no one has ever proposed that Standard Oil be reassembled in pre-1911 form.[68] ExxonMobil, however, does represent a substantial part of the original company.

Since the breakup of Standard Oil, several companies, such as General Motors and Microsoft, have come under antitrust investigation for being inherently too large for market competition; however, most of them remained together.[69][70][71] The only company since the breakup of Standard Oil that was divided into parts like Standard Oil was AT&T, which after decades as a regulated natural monopoly, was forced to divest itself of the Bell System in 1984.[72]

Successor companies

[edit]

Main article: Successors of Standard Oil

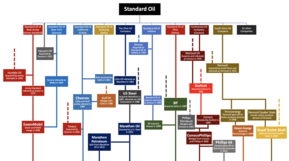

Standard Oil’s breakup split the company into 39 separate companies.[73] Several of these companies were considered among the Seven Sisters who dominated the industry worldwide for much of the 20th century, and both Standard Oil’s direct and indirect descendants make up Big Oil.

Today, Standard Oil’s influence is primarily concentrated in a few companies:

- ExxonMobil, continuation of Standard Oil of New Jersey (later Exxon) which merged with Standard Oil of New York (later Mobil)

- Chevron, continuation of Standard Oil of California which acquired Kentucky Standard

- BP, continuation of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company which acquired Standard Oil of Ohio and Standard Oil of Indiana

- Marathon Oil and Marathon Petroleum,[a] continuations of The Ohio Oil Company

- ConocoPhillips and Phillips 66,[b] continuations of the Continental Oil Company

Many of today’s largest oil and gas companies are or have acquired a descendant of Standard Oil. Moreover, many other companies have acquired or been created from Standard Oil descendants over time, including Unilever (which acquired Standard descendant Vaseline in 1987), TransUnion (created originally as a holding company for Standard descendant Union Tank Car) and Berkshire Hathaway (which later acquired Union Tank Car).[74][75]

Rights to the name

[edit]

Of the 39 “Baby Standards”, 11 were given rights to the Standard Oil name, based on the state they were in. Conoco and Atlantic elected to use their respective names instead of the Standard name, and their rights would be claimed by other companies.

By the 1980s, most companies were using their brand names instead of the Standard name, with Amoco being the last one to have widespread use of the “Standard” name, as it gave Midwestern owners the option of using the Amoco name or Standard.

Three supermajor companies now own the rights to the Standard name in the United States: ExxonMobil, Chevron Corp., and BP. BP acquired its rights through acquiring Standard Oil of Ohio and merging with Amoco and has a small handful of stations in the Midwestern United States using the Standard name. Likewise, BP continues to sell marine fuel under the Sohio brand at various marinas throughout Ohio. ExxonMobil keeps the Esso trademark alive at stations that sell diesel fuel by selling “Esso Diesel” displayed on the pumps.

ExxonMobil has full international rights to the Standard name, and continues to use the Esso name overseas and in Canada. To protect its trademark, Chevron has one station in each state it owns the rights to be branded as Standard.[76] Some of its Standard-branded stations have a mix of some signs that say Standard and some signs that say Chevron. Over time, Chevron has changed which station in a given state is the Standard station. As of December 2024 Chevron got a new federal trademark registered for the Standard name for its new electric charging fuel stations.

In February 2016, ExxonMobil successfully asked a U.S. federal court to lift the 1930s trademark injunction that banned it from using the Esso brand in some states. Neither BP nor Chevron objected to the decision. ExxonMobil asked for it to be lifted primarily so it could have universal marketing material for its stations globally and, likewise, the Esso name returned to some minor station signage at both Exxon and Mobil stations.[77][78]

As of 2021, six states that have the Standard Oil name rights are not being actively used by the companies that own them. Chevron withdrew from Kentucky (home of the Standard Oil of Kentucky, which Chevron acquired in 1961) in 2010, while BP gradually withdrew from five Great Plains and Rocky Mountain states (Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Wyoming) since the initial conversion of Amoco sites to BP. As ExxonMobil has stations in all of these states, with the aforementioned minor signage ExxonMobil has de facto claimed the Standard trademark in these states, though they are still held by their respective rights holders.

The Brookings Institution, often stylized as Brookings,[2] is an American think tank that conducts research and education in the social sciences, primarily in economics (and tax policy), metropolitan policy, governance, foreign policy, global economy, and economic development.[3][4] Brookings states that its staff “represent diverse points of view” and describes itself as nonpartisan.[5] Media outlets have variously described Brookings as centrist,[6] liberal,[7] and center-left.[8]

The University of Pennsylvania‘s Global Go To Think Tank Index Report has named Brookings “Think Tank of the Year” and “Top Think Tank in the World” every year since 2008.[9]

History

[edit]

20th century

[edit]

Brookings was founded in 1916 as the Institute for Government Research (IGR), with the mission of becoming “the first private organization devoted to analyzing public policy issues at the national level.”[10] The organization was founded on March 13, 1916, and began operations on October 1, 1916.[11]

Its stated mission is to “provide innovative and practical recommendations that advance three broad goals: strengthen American democracy; foster the economic and social welfare, security, and opportunity of all Americans; and secure a more open, safe, prosperous, and cooperative international system.”[12]

The Institution’s founder, philanthropist Robert S. Brookings (1850–1932), originally created three organizations: the Institute for Government Research, the Institute of Economics with funds from the Carnegie Corporation, and the Robert Brookings Graduate School affiliated with Washington University in St. Louis. The three were merged into the Brookings Institution on December 8, 1927.[4][13]

During the Great Depression, economists at Brookings embarked on a large-scale study commissioned by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to understand its underlying causes. Brookings’s first president, Harold G. Moulton, and other Brookings scholars later led an effort to oppose Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration because they thought it impeded economic recovery.[14]

With the U.S. entry into World War II in 1941, Brookings researchers turned their attention to aiding the administration with a series of studies on mobilization. In 1948, Brookings was asked to submit a plan for administering the European Recovery Program. The resulting organization scheme assured that the Marshall Plan was run carefully and on a businesslike basis.[15]

In 1952, Robert Calkins succeeded Moulton as Brookings’ president. He secured grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation and reorganized Brookings around the Economic Studies, Government Studies, and Foreign Policy Programs. In 1957, Brookings moved from Jackson Avenue to a new research center near Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C.[16]

In 1967, Kermit Gordon assumed Brookings’ presidency. He began a series of studies of program choices for the federal budget in 1969 titled “Setting National Priorities”.[17] He also expanded the Foreign Policy Studies Program to include research about national security and defense.

After Richard Nixon was elected president in the 1968 United States presidential election, the relationship between Brookings and the White House deteriorated. At one point, Nixon aide Charles Colson proposed a firebombing of the institution.[18] G. Gordon Liddy and the White House Plumbers actually made a plan to firebomb the headquarters and steal classified files, but it was canceled because the Nixon administration refused to pay for a fire engine as a getaway vehicle.[19] Yet throughout the 1970s, Brookings was offered more federal research contracts than it could handle.[20]

In 1976, after Gordon died, Gilbert Y. Steiner, director of the governmental studies program, was appointed the fourth president of the Brookings Institution by the board of trustees.[21][22] As director of the governmental studies program, Steiner brought in numerous scholars whose research ranges from administrative reform to urban policy, not only enhancing the program’s visibility and influence in Washington and nationally, but also producing works that have arguably survived as classics in the field of political science.[21][23]

By the 1980s, Brookings faced an increasingly competitive and ideologically charged intellectual environment.[24] The need to reduce the federal budget deficit became a major research theme, as did problems with national security and government inefficiency. Bruce MacLaury,[25] Brookings’s fifth president, also established the Center for Public Policy Education to develop workshop conferences and public forums to broaden the audience for research programs.[26]

An academic analysis of congressional records from 1993 to 2002 found that Brookings was cited by conservative politicians almost as often as by liberal politicians, earning a score of 53 on a 1–100 scale, with 100 representing the most liberal score.[27] The same study found Brookings to be the most frequently cited think tank by U.S. media and politicians.[27]

In 1995, Michael Armacost became the sixth president of the Brookings Institution and led an effort to refocus its mission heading into the 21st century.[28] Under his direction, Brookings created several interdisciplinary research centers, such as the Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy, now the Metropolitan Policy Program led by Bruce J. Katz,[29] which brought attention to the strengths of cities and metropolitan areas; and the Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies, which brings together specialists from different Asian countries to examine regional problems.[30]

21st century

[edit]

In 2002, Strobe Talbott became president of Brookings.[31] Shortly thereafter, Brookings launched the Saban Center for Middle East Policy and the John L. Thornton China Center. In 2006, Brookings announced the establishment of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center in Beijing. In July 2007, Brookings announced the creation of the Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform to be directed by senior fellow Mark McClellan,[32] and in October 2007 the creation of the Brookings Doha Center directed by fellow Hady Amr in Qatar.[33] During this period the funding of Brookings by foreign governments and corporations came under public scrutiny (see Funding controversies below).

In 2011, Talbott inaugurated the Brookings India Office.[34][35]

In October 2017, former general John R. Allen became the eighth president of Brookings.[36] Allen resigned on June 12, 2022, amid an FBI foreign lobbying investigation.[37]

As of June 30, 2019, Brookings had an endowment of $377.2 million.[38]

Brookings operated three international centers: in Doha, Qatar (Brookings Doha Center); Beijing, China (Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy); and New Delhi, India (Brookings India). In 2020 and 2021, the Institution announced it was separating entirely from its centers in Doha and New Delhi, and transitioning its center in Beijing to an informal partnership with Tsinghua University, known as Brookings-Tsinghua China.[39]

Publications

[edit]

Brookings as an institution produces an Annual Report.[40] The Brookings Institution Press publishes books and journals from the institution’s own research as well as authors outside the organization.[41] The books and journals it publishes include Brookings Papers on Economic Activity,[42] Brookings Review (1982–2003, ISSN 0745-1253),[43][44] America Unbound: The Bush Revolution in Foreign Policy, Globalphobia: Confronting Fears about Open Trade, India: Emerging Power, Through Their Eyes, Taking the High Road, Masses in Flight, US Public Policy Regarding Sovereign Wealth Fund Investment in the United States[45] and Stalemate. In addition, books, papers, articles, reports, policy briefs and opinion pieces are produced by Brookings research programs, centers, projects and, for the most part, by experts.[46][47] Brookings also cooperates with The Lawfare Institute in publishing the online multimedia publication Lawfare.[48]

Policy influence

[edit]

Brookings traces its history to 1916 and has contributed to the creation of the United Nations, the Marshall Plan, and the Congressional Budget Office, as well as to the development of influential policies for deregulation, broad-based tax reform, welfare reform, and foreign aid.[49] The annual think tank index published by Foreign Policy ranks it the number one think tank in the U.S.[50] and the Global Go To Think Tank Index believes it is the number one such tank in the world.[51] Moreover, in spite of an overall decline in the number of times information or opinions developed by think tanks are cited by U.S. media, of the 200 most prominent think tanks in the U.S., the Brookings Institution’s research remains the most frequently cited.[52][53]