This morning I found out David is a fellow Bohemian and Lamp Freak Also, folks are making lamps from cremation urns. I have made great lamps and was going to sell them at the Saturday Market.

Below is a quote that David would – love to death! He would be happy – that he surprised me! I was….not aware! I can’t even – spell it!

JRP

“David spoke about his Transcendtal Meditation, but, regrets he did not take the last step into the light like I did, when I became a seeker of Weird Lamps in Goodwill and Saint Vincent De Paul stores. I drove down 99 in my quest in my 1972 Ford pickup.. Alas I found, not one – but two Grails. You can see in this video….I am a happy man!”

Yes, David Lynch lived the life of a bohemian painter in Philadelphia before becoming a filmmaker. He envisioned a bohemian lifestyle as a teenager, and his work is said to be a mix of the unworldly and the bohemian.

Explanation

- As a teenager, Lynch imagined a bohemian lifestyle of drinking coffee, smoking cigarettes, and dating.

- He lived in a crime-ridden area of Philadelphia with his wife and baby daughter.

- His first short films featured scenes of blood, vomiting, and crying babies.

- Lynch’s work is often associated with “New American Gothic”, which depicts violent menace and sexual and physical aberrancy.

430 miles from the Bohemian Grove

LAMPS OF LYNCH: TWIN PEAKS, PILOT AND SEASON 16/13/20180 CommentsI’m always looking for new ways to enjoy watching through David Lynch’s filmography. One thing I notice each and every time I work through it is how beautiful and fastidiously placed the props always are. In Twin Peaks: The Return, I was especially dazzled by all the sculptural elements in play and fell in love with any number of the gorgeous lamps on display. The intentional and prominent placement of lamps in key scenes–from broken flashlights to midcentury modern museum pieces–seemed to be such a pervasive thematic presence throughout The Return that it got me to wondering what I might find if I watched back through the entire corpus–from the short films and Eraserhead all the way through Twin Peaks Season 3–with eyes peeled for noteworthy lamps. My curiosity on this score has resulted in a new Instagram project, Lamps of Lynch: Finding Light in the Work of David Lynch. If you follow lampsoflynch, you’ll get a guided tour of the whole nine yards: every single noteworthy lamp, torch, lightbulb, fixture, flashlight, candle, candelabra, and chandelier from Short Films, Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune, Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks (Pilot, Seasons 1 and 2), Wild At Heart, Fire Walk With Me, Lost Highway, The Straight Story, Mulholland Drive, Inland Empire, and Twin Peaks (Season 3). The results so far have brightened up the last couple of weeks for me and produced some illuminating insights into the prominent role of light in Lynch’s films even and especially in some of the very darkest scenes. I just finished working my way through Twin Peaks Pilot and Season 1 and decided to make these light-filled images available to readers at THE GLASS BOX who may not follow Instagram. I’ll make sure to follow up with similar posts for Fire Walk With Me and Seasons 2 and 3 as time allows. Press PLAY in the top left corner of the featured image below to start a slideshow or peruse the thumbnails above the featured image to choose a specific image.  https://www.facebook.com/v2.6/plugins/like.php?action=like&app_id=190291501407&channel=ht https://www.facebook.com/v2.6/plugins/like.php?action=like&app_id=190291501407&channel=ht |

La dernière panique

The Riddle of Lumen: Lynch’s Lamps

In a gallery exhibition of new work, David Lynch’s functional sculptures evoke the uncanny existence of light and darkness in his art.

•

17 Jan 2023

David Lynch, Red Zig-Zag (2022), © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

I imagine that everyone who came to see David Lynch’s “Big Bongo Night” exhibition at the Pace gallery in New York last autumn was probably already familiar with Lynch’s movies and television. Though he has been making paintings for decades (not to mention sculptures, music, coffee, and daily weather reports), the word “Lynchian” typically applies to films like Eraserhead (1977) and Lost Highway (1997), for which he is far better known. You, too, have come across this article because you are reading a film journal. In this sense, the exhibition did not disappoint. The large-scale paintings featured motifs recognizable from his cinematic worlds: multiplied and sometimes exploded heads, snippets of banal yet unnerving dialogue, dream worlds collapsed into waking ones. Despite the shift in medium to canvas, heavily caked paint, and at least one Band-Aid, these works were familiar and creepy, creepily familiar. Blunt, smudged, and lumpy, all the works appeared deliberately handmade, with the uncanny simplicity of outsider art. I snapped a photo of a tiny clay head, with sunken eyes and delicately poked nostrils, at which a pencil-drawn arrow pointed the words: “what the FUCK?”

Then there were the lamps. Watching a Lynch film teaches you to notice—and fear—the things that don’t fit, because they often come back later. In the gallery, I spent most of my time peering into the paintings, but found myself later unnerved by the lamps. There were eleven in all, and like the paintings, most had been made in 2022 or the past several years. Nine stood in the center of the gallery floor, along two sides of a half-wall. They were arrayed evenly in a row, as if on display in a furniture store. Like many lighting fixtures in Lynch’s films, these spindly ciphers had unusually small, dim heads. One, “Love Light #2,” glowed weakly red from atop a long, hand-chiseled pole. A set of four nearly identical lamps were laid out along one side, their heads made out of different blocks of wood varieties but cut in the same sharp, accordion fold. Each shone in ascending brightness, though never rising above accent wattage. “Red Zig-Zag,” which stood at the fore, featured a long passage up to what resembled a tiny, demonic phone booth.

The works were listed as “sculptures with light components,” but they were undeniably lamps. For one, they had black cables, not altogether drawn tightly, leading back to the half-wall that powered them. They also had switches. These were small, but often centrally and noticeably placed. In “White Table Top Lamp,” the switch protruded like a belly button from the bone-white resin base. The switches indicated that they were furniture. They were functional. If I were bolder I would have tried flicking one off.

David Lynch, Big Bongo Night (installation view), courtesy Pace Gallery.

The lamps posed a riddle: what was their function, here, in this room? Elsewhere in Lynch’s films, interiors are typically dingy and dark, warmed with a vellum shade, like the small red one by Diane’s phone in Mulholland Dr. (2001), or the Tiffany lamp that festoons Isabella Rossellini’s mauve den in Blue Velvet (1986). These are useless, say, for reading. Here, the lamps had the effect of turning the gallery space into a Lynch interior. Though the ambient light from the ceiling was brighter than most of his films, the lamps created a similarly quiet and eerie setting. With the windows additionally covered with heavy gray curtains, it was, as a man recounts of a dream in Mulholland Dr., “not day or night, it’s kind of half night. But it looks just like this. Except for the light.”

Light defines a space, making it knowable and finite. In Lynch’s films, there is another kind of light, one that intrudes on and deranges a space. Violence erupts through this light: bright, blue-white flashes, spotlights, and strobes. These are otherworldly manifestations, like the troupe of Polish prostitutes who inexplicably appear and dance the “Locomotion” before a pulsing glare in Inland Empire (2006). While some lights, like the Big Bongo lamps, have an identifiable electrical source, these lights are unlocatable, annihilating and occasionally sublime. (Tellingly, the fluted floor lamps in Twin Peaks’s mysterious Black Lodge don’t emit any light, nor do they have cables.) They can also suddenly disappear, as when the Palmer house goes dark at the end of Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). The known, illuminated place, comes undone. In darkness, it becomes anywhere.

A unique feature of Lynch’s films is the absence of pathology. There is no psychoanalytic key to resolve the disorder; like these otherworldly lights, there is no source. It’s beside the point to explain the motives of the grinning Mystery Man of Lost Highway or Frank Booth’s “baby” persona in Blue Velvet. Though detectives abound in Lynch’s films, the abundant sadism and cruelty of his worlds are not mysteries to be solved. Instead, they are features of the nightmare itself. The lights, too, are not reflections of interior states in any expressionist sense. In a real sense, they are the Manichean forces whose struggle plays out in otherwise unassuming locations: living rooms, bedrooms, bars, diners, gas stations, roads traversed at night. These are familiar to us, “except for the light.”

The lamps of Big Bongo Night had a function, and that was to turn the gallery into an interior open to sudden, shocking disturbances. This is what followed me in the days and weeks after I’d visited the show. Maybe it was the smile on the half-exploded head of someone labeled “Billy???” in “I Call Out Your Name,” the crossed-out words in “He Went and He Did Do That Thing,” or the ominously titled “Car Accident by my House.” The bad thing might have already happened, or was yet to come—in Lynch’s work, both are usually true. But what was more unnerving, what had me looking over my shoulder after I’d left, was the sensation that these forces were not tidily contained in their frames on the walls. The lamps had put me in the space with them, touched by the same, dark glow.

David Lynch, He Went and He Did Do That Thing (n.d.), © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Don’t miss our latest features and interviews.

David Lynch’s most iconic real and fictional spaces

Interiors, News I 17.01.25 I by Betty Wood and Rosella Degori

Courtesy Sky Atlantic

Over his 50-year career, David Lynch created some of cinema’s most iconic visual spaces, from the psychologically charged Red Room in Twin Peaks to Club Silencio in Mulholland Drive. Following the director’s death this week, aged 78, we take a look at his spatial legacy – celluloid sets that became characters in their own right and the real-world interiors he left behind.

A Thinking Room – Milan

Lynch launched his cinematic installation A Thinking Room at the Rho Fiera during last year’s Salone del Mobile in Milan (16-21 April 2024), teaming up with curator Antonio Monda on the immersive installation. Two identical ‘Thinking Rooms’ embodied his auteurial language and passion for furniture design; each featured a single, oversized throne-like armchair designed by Lynch (himself a passionate furniture designer) and surrounded by heavy blue velvet drapes – a reference to his 1986 hit, Blue Velvet. Overhead, brass tubes reached towards a gilded ceiling, while screens on the outskirts of the space played abstract videos, offering a ‘glimpse’ of the world beyond the room.

The ephemeral Thinking Room was conceived as a space for reflection and pause, away from the bustle of the fair. Lynch drew all the concept sketches for the exhibition design, and his vision was brought to life by the Milanese firm Lombardini22 and set designers from the Piccolo Theater.

Red Room – ‘Twin Peaks’ (1990, 2017)

Arguably, his most iconic set design, the Red Room has inspired and intrigued generations of cinema-goers. Crimson red curtains envelop the space, with a black-and-white chevron patterned floor adding a hypnotic touch, giving the space the eerie feeling of being out of sync with time and reality. Lynch was particularly interested in the psychological impact of colours and motifs: red is a recurrent visual cue to convey a sense of paranoia, dread and fear, with the director using his recurrent red curtains in Twin Peaks, Eraserhead, Blue Velvet and Lost Highway.

See more on Twin Peaks season 3’s scene-stealing set designs.

‘Rabbits’ (2002) living room

Rabbits is a series of eight short horror web films Lynch wrote and directed in 2002 about a trio of humanoid rabbits voiced by Scott Coffey, Laura Elena Harring and Naomi Watts. All of the action and conversation takes place in the living room, which quickly becomes the fourth character as the series progresses.

Poorly lit, with dramatic shadows dancing across its walls and ceiling, Rabbits’ living room has a monochrome palette of dark, muted tones and spartan furniture that seems to embody the drabness and depression of the characters who inhabit the room. The vintage-style midcentury sofa is arranged off-kilter, adding to the psychological tension of the space. At the same time, you can’t see through the room’s singular window, adding to the sense of claustrophobia and anxiety about what lies outside.

Betty’s apartment, ‘Mulholland Drive (2001)’

Obscure and impenetrable, Mulholland Drive explores Lynch’s recurrent theme of doubling, among other things, and is an uncanny journey through Los Angeles’s underbelly, exploring its seductive yet frightening nature. The plot follows aspiring actress Betty Elms’ arrival in the city to stay in her aunt’s vacant apartment in Hollywood. Here, she encounters Rita, who appears lost and confused and eventually becomes her love interest.

Betty’s fictional apartment is actually located in the real life, historic Il Borghese Apartments in Hancock Park, near West Hollywood. Designed by architect Charles Gault in 1929, this building is a striking example of Spanish architecture, complete with a leafy courtyard and a fountain. It is also said to have been the former residence of Shirley Temple and a popular party venue for many Hollywood personalities, including Errol Flynn.

Madison House – ‘Lost Highway’ (1997)

Considered by many Lynch fans to be the thematic ‘sequel’ to Blue Velvet (1986), Lost Highway continues Lynch’s exploration of duality, fluid identities, and the hidden, dark side of mundane life. Protagonists Fred and René Madison (Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette) live in the angular Hollywood Hills home; their ordinary lives are disrupted when they begin receiving video tapes through their door, and Fred suspects his wife of infidelity.

In real life, the property was owned by Lynch (among three on the same street, including a residence designed by Frank Lloyd Wright’s son, Lloyd Wright). From the outside, the concrete fortress encapsulates Fred’s paranoid state of mind, while the minimalist interior has those signature red curtains and large, empty rooms with furniture floating in negative space. Low ceilings and winding corridors add to the sense of disruption and paranoia.

Henry’s apartment – Eraserhead (1977)

Never has an interior embodied a character’s dismal psychological state quite so well as Henry’s apartment in Lynch’s 1977 film Eraserhead. The room is small, sparsely furnished, and dirty: the walls look dingy with peeling wallpaper, the bed is unkempt with dirty bed sheets, and there’s little else beyond the radiator, a small table and a nightstand. Like Rabbits’ living room, the space is shadowy and dimly lit, manifesting Henry’s psychological anxiety as a visual cue for the audience as he unravels.

Silencio Paris

David Lynch took cues from his fictional Club Silencio, featured in Mulholland Drive when creating this real-life private members’ club in Paris back in 2011. Everything from the 1950s furniture to the black toilet bowls was conceived by the director in his role as Silencio’s artistic director, and it’s designed to ‘induce and sustain a specific state of alertness and openness to the unknown’.

Since then, the Silencio portfolio has expanded to NYC. And though Lynch was not directly involved in the design of the Manhattan clubhouse, it was done in collaboration with his original Silencio Paris. Consequently, the Manhattan space mirrors the concept of the Parisian club.

Crosby Studios founder Harry Nuriev designed the Manhattan outpost’s interiors and they’re every inch the David Lynch fever dream, distilling the director’s visual language through the use of red curtains and LED strips outlining the walls. Stepping into the space feels like you’re stepping into a slippery Lynchian world.

Read next: 10 real-world locations from David Lynch’s film catalogue

New York nightclub Silencio is a David Lynch fever dream

ERUPTIONS OF THE STRANGE: ON DAVID LYNCH’S LAMPS

David Lynch, Zebrawood Top Lamp, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

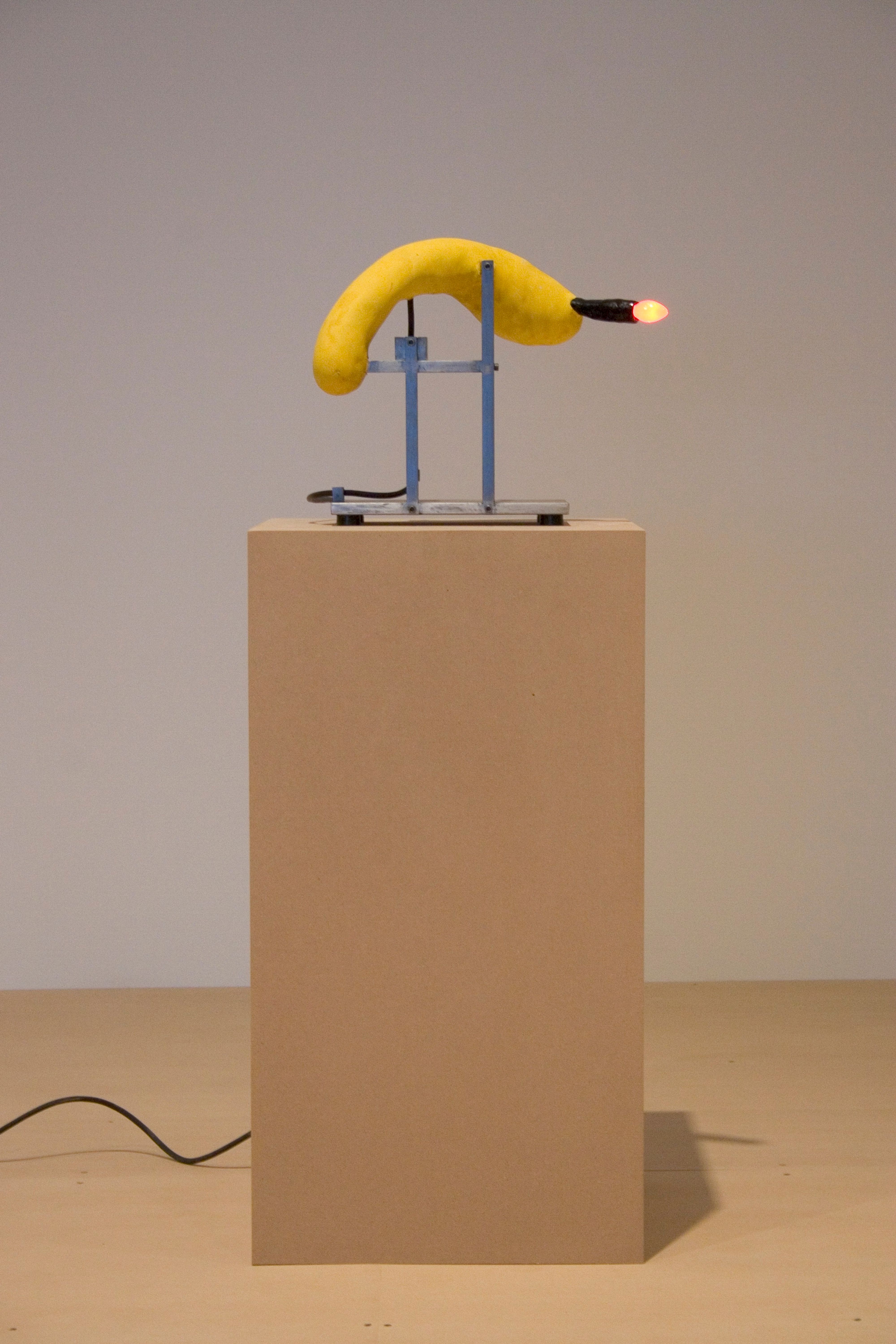

Consider David Lynch, lamp designer. In his Red Black Yellow Table Lamp (2011), a libidinal red pustule glows at the tip of a septic yellow phallus, fixed in place by an assemblage of orthogonal metal rods and plates. Its elegant brutality suggests Gerrit Rietveld-designed laboratory equipment. The lamp provides precisely enough light to be useless. On Planet Lynch, seeing clearly is less important than seeing with feeling.

Even people unversed in design history will notice Lynch’s unusual handling of the lamp’s cord. It seems to represent a restraining leash, as though to keep the phallus from wriggling away. On an overlapping wavelength, it expresses architectural Modernism’s fetish for control. Lynch’s cord — a loose, flaccid material — is disciplined by a series of rectilinear metal standoffs, which opens up a third reading: the cord as umbilical. It both supplies a vital current of electricity and it might be severed, setting free the phallus in question. Vitality, repression, architectural critique. What more can we ask of a lamp cord?

David Lynch, Red Black Yellow Table Lamp, 2011. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

A feeling of decisive precision pervades Lynch’s designs. There is a sense that his lamps have arrived at their forms through a process of calculated reasoning. This impression rubs against the precarity of many of his structural choices — in which ad hoc solutions just short of bubble gum hold things together. See, for instance, Love Light #2 (2022), in which the transition between the joined wooden rod and the lightbulb fixture appears to be a wadded smush of epoxy clay.

Lynch is a quixotic individual. For about nine hundred consecutive days he maintained a YouTube account dedicated to two jaw-droppingly mundane daily video series, produced by the auteur with what appears to be a foggy phone camera. In the first series, he picks “today’s number” out of a jar, announcing it with utter sincerity before finishing his script with the text overlay “WHAT WILL TOMORROW’S NUMBER BE?” These videos are as uninterpretable as the portions of his films that critics alternately describe as “inscrutable,” “self-indulgent” and “savagely uncompromising.” Perhaps predictably, they have their own cult following — with initiates creating highly involved interpretations and representations of the selected numbers. In the second series, Lynch provides the daily weather report, interspersing observations like, “It looks like these clouds are going to remain until late afternoon,” with such ponderings as: “I’m thinking about tree trunks and epoxy.” This banality is its own kind of provocation from a man better known, in his precocious youth, for making the film Blue Velvet, in which a psychotic lunatic in a bolo tie opens a scene with, “Shut up! It’s daddy you shithead!”, before huffing nitrous oxide and spluttering on the ground, rising to his knees, demanding his blackmail victim spread her legs, and plaintively addressing her vagina as “mommy” while proceeding to rape her. Lynch also founded a school of transcendental meditation.

The impulse to associate Lynch’s films with his furniture designs may at first seem specious, but as a director he often replaces narrative logics with choreographed atmospheres in which lamps, curtains, and characters diffuse into mood. These moods can be so engrossing that you simply forget, moment to moment, that you don’t know what is going on — or that such knowledge becomes insignificant in comparison to the overwhelming stimulation of the sensual input. In Inland Empire, long shots of ominously amber-colored lampshades are central to the creeping sense of menace. Some of Lynch’s directorial fixations with objects and interiors might be ascribable to his admiration for another filmmaker, the French comic master Jacques Tati. Tati’s crowning achievement, Playtime, is spun out from nothing more than the disastrous interactions between a protagonist and squeaky International Style chairs, anonymous office building façades, and impatient automatic doors. Modernism is the film’s sole antagonist and plot-driver.

David Lynch, Love Light #2, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

David Lynch, Clear Top Lamp, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Lynch has a keen sense of how small changes to the familiar can detonate cataclysmically. Throughout Eraserhead, a plant sits on the protagonist’s bedside table without a pot. What is a potted plant without its pot? Ungoverned nature: something which can, if not suppressed, destroy an entire house, an entire city. Nothing more than a ceramic shell insulates cozy domesticity from this whirlpool of anarchy, atavism, and ominous possibility.

David Lynch is a world maker — and what that means, critically, is that he is not above being a lamp maker. A separate question to puzzle over is why any lamp maker would not have designs on the world. A room, after all, shapes the presence of the lamp. And rooms are modeled by the spaces which precede them, the spaces that enmesh them, and the glimpses they offer of what lies beyond. Our perceptions of luminosity and color temperature are connected to the natural light conditions at a given moment, so a skilled lamp designer may need to adjust the sun to better suit the lamp.

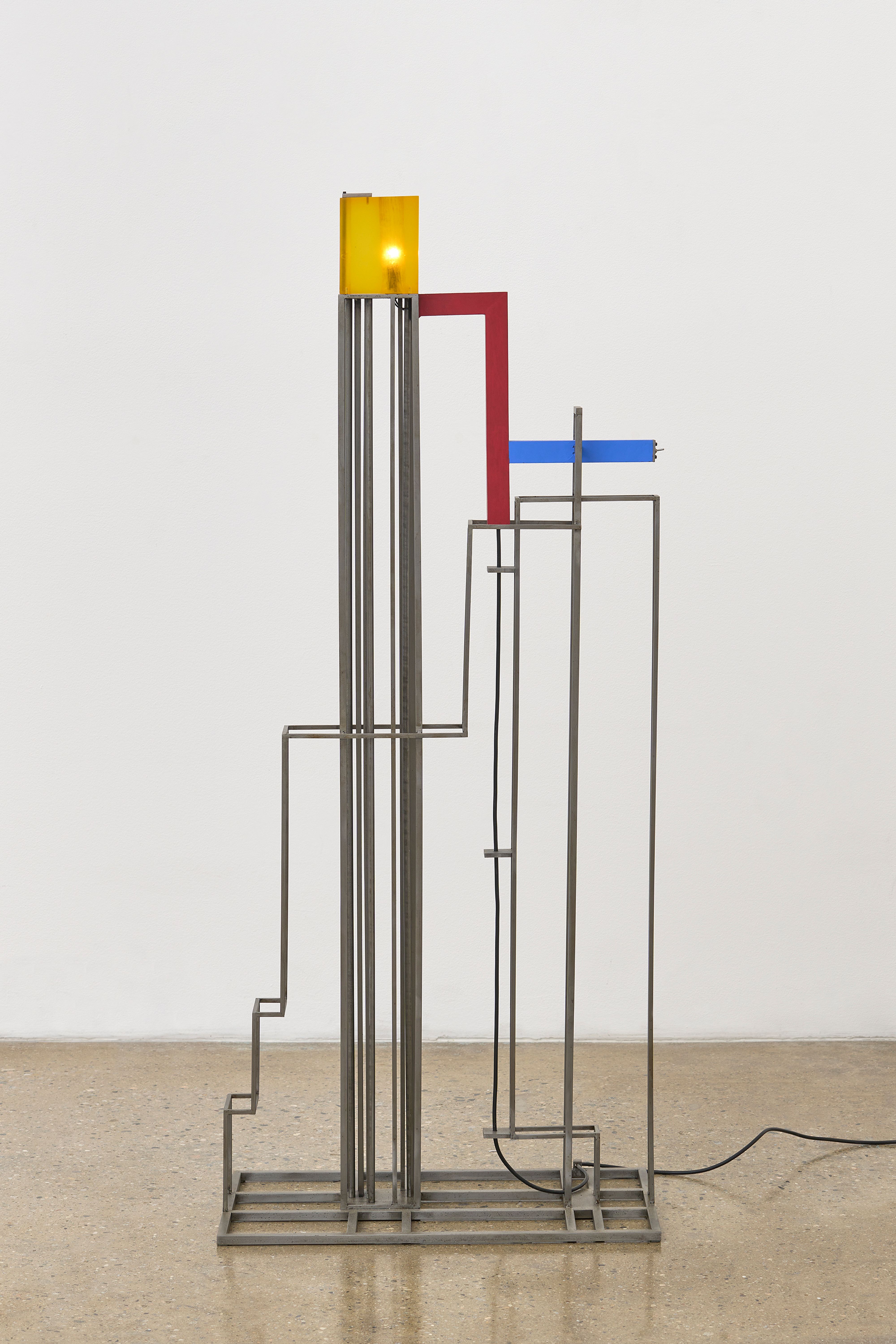

David Lynch, Tricolor Highrise Lamp, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

In interviews, Lynch has expressed a fondness for the Bauhaus. Like other modernisms, that movement was distinctly utopian — it took as a premise that design might reshape humanity at large. It was also a set of aesthetic preferences: rectilinearity, primary colors, expressive structures, undisguised joinery. All of these can be found in Lynchian works including Tricolor Highrise Lamp (2022). Lynch peels away Modernism’s performative rationalism and relishes its underlying craziness — in which repression descends into fetish. Think of Adolf Loos’s lush, carpeted interiors in relation to his stark raving mad anti-ornamentalist invectives (see his “Ornament is Crime”). Lynch too has utopian inclinations. He says his mission in founding a school of transcendental meditation is to lead humanity into an “ocean of pure, vibrant consciousness.” Out there, in the ocean, the light looks strange.

Leave a comment