There are no hits when you Google Ken Kesey and Frodo. How – odd! “Frodo lives!” was a Hippie motto.

“A longtime fan of the Marx Brothers, Tolkien was a prankster even in his youth. When Tolkien attended Oxford as a young adult, he had a reputation as a joker: as a freshman, he started a club called the Apolausticks, “those who are devoted to self-indulgence,” and once he and a friend leapt inside an empty bus and drove around picking up other students and making speeches to the crowd that had assembled.”

Here is a good article about Ken’s book series, which can be considered his….BLOG? Forrester talks about the house Ken and Faye lived in when I attended the New Hope program as Serenity Lane. You can see the house from the third floor balcony of the quad I lived in in 16th. I was very tempted to drop in, or, call Nancy to get me an invite. But I was afraid Ken and I would be in a bar within an hour of meeting. It would be a two day drunk – with drugging! I would blow his mind! An hour ago, I figured out why. My friend Bill Arnold and I invented a New Bohemianism – for twelve year old boys – in 1959! Kesey hadn’t even started yet. Nancy was Bill’s lover, We did pranks and art events all the time. But, here’s the rub……I did not go get stoned with Ken! I chose to get sober, and own an alternative way of life, which meant, being…….nothing like Ken Kesey! I did this with the help of my brother’s in AA.

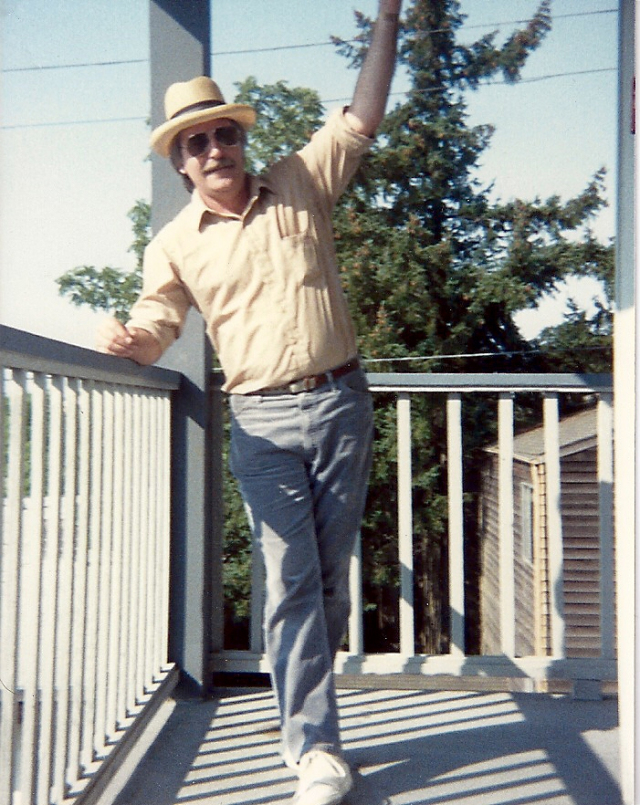

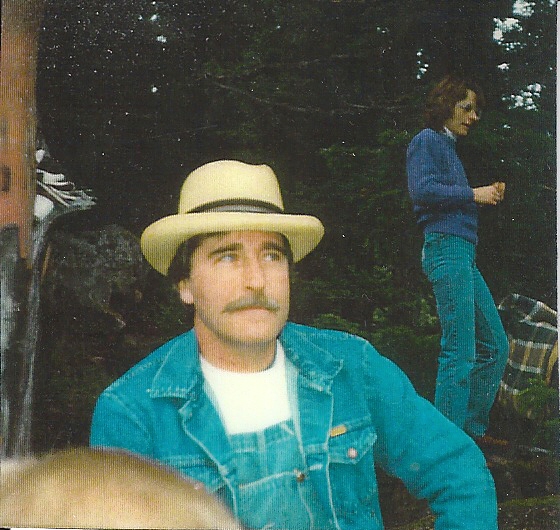

That’s a pic of me getting off the train in Eugene in 19 86. In the other pic I am at a waterfall with Dianne Dundon, whose grandson shot himself in April of 2024. I found out twenty minutes after I discovered my niece Drew Benton took her life. Dianne is three generation Fynn Rock. She married Michael Dundon, who worked for a couple of old logging companies. She ran the Whitewater Cafe in Blue River that burned down. Michael became a cook at the Cougar Room and the Log Cabin Inn. Gone!

A friend thinks I have the longest blog in the world. I lost the previous one. I am thirty eight years sober? I am alive! I write all……..ALONE! I tried being not ALONE with a writing group. They almost lynched me! There were two people there who were not writers! They were…..J

SPRINGFIELD JUDGERS – looking to get their kicks!

“Frodo lives!…..without drugs and alcohol!”

JP

Writing Group of the Damned

Posted on February 16, 2020 by Royal Rosamond Press

Memoirs #10479

Idea For a Series

by

John Presco

Copyright 2020

An old Hippie, who was on the bus with Ken Kesey, joins a writing group and starts with memoirs of his childhood gang ‘The Cheetah’s. He makes the mistake of telling this group he knew Nancy, and met Ken – several times. He compounds this blunder with playing Patten’s famous words about Rummel that severely agitates another member of the group that wrote a small book about a War Hero, and served time in Vietnam.

J.R.R. Tolkien loved to pull pranks on his students.

January 3, 2022, 3:58pm

Today marks the 130th birthday of J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings writer, academic, and, as it turns out, prank enthusiast. It makes sense that the mind behind the extensive lore and joyful traditions of Middle-earth would embrace a sense of play in the everyday; but Tolkien took his love of pranks to Improv Everywhere levels of extreme.

A longtime fan of the Marx Brothers, Tolkien was a prankster even in his youth. When Tolkien attended Oxford as a young adult, he had a reputation as a joker: as a freshman, he started a club called the Apolausticks, “those who are devoted to self-indulgence,” and once he and a friend leapt inside an empty bus and drove around picking up other students and making speeches to the crowd that had assembled.

Years later, when he was a don at Oxford, he was known for “dress[ing] up as an Anglo-Saxon warrior with an ax and chas[ing] an astonished neighbour”; this was apparently a stunt he pulled multiple times. He pulled pranks while lecturing as well; apparently he would occasionally pull a four-inch green shoe from his pocket as “proof that leprechauns exist.” (Sending up academia? Is this guy a Brooklyn alt comic in 2016?)

He loved costumes—once he and C.S. Lewis went to a party dressed as polar bears, in sheepskin and whiteface. No, it wasn’t a costume party; he just did this for fun.

And Tolkien’s playful streak persisted through old age: often he handed shopkeepers his false teeth when he was giving them change. This guy!

Wrote Tolkien, “I have a very simple sense of humour, which even my appreciative critics find tiresome.” I wouldn’t call dressing up as an axe-wielding Anglo-Saxon warrior simple—but I can understand how to even an appreciative shopkeeper, the false teeth gag could grow tiresome.

Hobbits and hippies: Tolkien and the counterculture

19 November 2014ShareSave

Jane Ciabattari

Features correspondent

JRR Tolkien was a deeply religious Oxford professor and World War I veteran – but his works had a huge impact on the ‘60s counterculture. Jane Ciabattari reports.

It was a time of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Not to mention protest against the Vietnam War and marches for civil rights and the women’s movement. Who would think a figurehead for this social upheaval would be a tweedy Christian philologist at Oxford? But during the 1960s, a time of accelerating social change driven in part by 42 million Baby Boomers coming of age, Tolkien’s The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings became required reading for the nascent counterculture, devoured simultaneously by students, artists, writers, rock bands and other agents of cultural change. The slogans ‘Frodo Lives’ and ‘Gandalf for President’ festooned subway stations worldwide as graffiti.

Middle Earth, JRR Tolkien’s meticulously detailed and mythic alternate universe, was created against the backdrop of two world wars. As a professor at Oxford , Tolkien taught Anglo-Saxon, Old Icelandic and medieval Welsh and translated Beowulf, which inspired his later monsters. His fantasy vision, and his sense of evil looming over the good life, was shaped by his devout Catholicism and his experience serving in World War I, in which he lost all but one of his close friends. “The Dead Marshes and the approaches to the Morannon owe something to northern France after the Battle of the Somme,” he wrote in a 1960 letter. Frodo and Sam struggling to reach Mordor is a cracked mirror reflection of the young soldiers caught in the blasted landscape and slaughter of trench warfare on the Western Front.

For decades, fans have been obsessed with Tolkien’s Great War of the Ring, with its wizards and magicians, the legions of hobbits, dwarves, elves, orcs, giants, ents, the dragon Smaug guarding his treasure and the threatening Dark Lord. They were popular initially but sales of The Hobbit (published in 1937) and The Lord of the Rings (beginning in 1954) exploded in the mid-1960s, driven by a young generation charmed by Tolkien’s imaginative abundance, the splendour of his tales from a pre-Christian time and his obsessive cataloguing of the history, language and geography of his invented world. But deeper than this, certain aspects of Tolkien’s worldview matched the perspective of hippies, anti-war protestors, civil rights marchers and others seeking to change the established order. In fact, the values articulated by Tolkien were ideally suited for the 1960s counterculture movements. Today we’d think of Tolkien’s work as being aligned with the geek set of Comic-Con, but it was once closer to the Woodstock crowd. How did this happen?

A real trip

The drug culture of Tolkien’s novels may have served as an initial hook for the Boomer generation. Many of the characters of Middle Earth are drawn to hallucinogenic plants. The ‘little people’ in the Shire used hallucinogenic drugs, mostly “the herb called pipeweed”. Even the dark wizard Saruman, who was curious about the Shire because Gandalf showed an interest, had taken to the “halflings’ leaf”. He was sceptical of it too: Saruman says to Gandalf in Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring, “Your love of the halflings’ leaf has clearly slowed your mind”.

Advertisement

The high fantasy of The Lord of the Rings was “hobbit-forming,” as T-shirt slogans of the ‘60s and ‘70s put it. “A whole generation of young Americans could lose themselves and their troubles in the intricacies of this triple-decker epic,” said Professor Ralph C Wood, a Tolkien scholar. Middle Earth was a literary escape hatch for a generation haunted by the Vietnam War and the atomic bomb, a return to simple living. Many felt the experience of reading the text itself is akin to an acid trip. According to Wood, “Indeed, the rumour got about – a wish seeking fulfillment, no doubt – that Tolkien had composed The Lord of the Rings under the influence of drugs.”

Also appealing to the burgeoning anti-war, feminist and civil rights movement activists was Tolkien’s political subtext of the ‘little people’, the Hobbits, and their wizard ally, leading a revolution. The military industrial complex targeted by protestors resembled Mordor in its mechanised, impersonal approach to an unpopular war. When he is drafted into bearing the Ring to Mount Doom, Frodo feels an “overwhelming longing to rest and remain at peace… in Rivendell.” Those who led the fight against Sauron’s army stood reluctantly, hoping this would be the “War to End All Wars”.

Likewise, Lady Éowyn of Rohan, struggling to overcome the limits of patriarchal society, answered Aragorn’s question, “What do you fear, lady?” with lines that resonated among the second wave feminists of the 1960s: “A cage,” Éowyn said. “To stay behind bars, until use and old age accept them, and all chance of doing great deeds is gone beyond recall or desire.”

Tolkien’s anti-materialistic worldview, in which he extolled the wonders of growing things and of the ordinary – “stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine”, as he put it in his 1947 essay On Fairy-Stories – also dovetailed with the countercultural values. Some hippies built hand-crafted houses, went back to the land to grow organic vegetables, wore simple clothing, ate vegetarian meals and lived communally, all seemingly in keeping with the pleasurable simple life in the Shire. Earth Day, which launched the environmental movement in 1970, with 20 million Americans rallying from coast to coast in a rare show of bipartisanship, aligned with Tolkien’s glorification of nature, clean and pure, and his distaste for the polluting aspects of industrialisation. (This was a professor who rode his bicycle instead of driving a car.)

Mordor matters

Tolkien’s literary world directly inspired some of the most high profile agents of change within the counterculture. Rock bands whose anthems served as a soundtrack for the upending of the establishment clearly read Tolkien’s work. In the 1960s the Beatles envisioned a film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings – Paul as Frodo, Ringo as Sam, George as Gandalf and John as Gollum – that never came to fruition. Pink Floyd’s 1967 song The Gnome featured a little man named Grimble Grumble in a red tunic, and others like him in their homes, who were, like the hobbits, “Eating, sleeping, drinking their wine.”

In 1970, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Genesis all had Lord of the Rings-themed songs on the charts. In the opening verse of Led Zeppelin’s Ramble On, Robert Plant sings, “’Twas in the darkest depths of Mordor/I met a girl so fair/But Gollum and the evil one crept up…” Two 1971 Led Zeppelin songs, Misty Mountain Hop and The Battle of Evermore, in which the “ring wraiths ride in black”, also were inspired by Tolkien. Black Sabbath’s The Wizard is an anthem for Gandalf. Genesis’ Stagnation was clearly influenced by the Middle Earth ethos. Rush recorded Rivendell, based on the Elven homeland, in 1975 and followed in 1976 with The Necromancer (Tolkien’s original name for Sauron), who keeps watch with “magic prism eyes.”

This ground-breaking music mirrored the mind-expanding drugs, magical excursions, pagan celebrations and Bohemian lifestyle associated with the counterculture – and characters in Tolkien’s books.

It’s hard to imagine anyone today watching The Lord of the Rings or Hobbit films and thinking of alternative lifestyles or radical activism. What happened?

Tolkien himself would possibly be horrified by the multiplatform industry built upon his work. Today his saga is best known through Peter Jackson’s multi-billion-dollar-grossing movies. In these blockbuster films, Tolkien’s intricate narrative arc has been scaled beyond its original humanity and reduced to CGI eye-candy. The spirit of his work remains, in his original texts. Go there to the books, and rediscover Tolkien the mythmaker, the believer in the mysteries of faith and storytelling. And someone who was once so square he was cool.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

Ken Kesey

SPIT IN THE OCEAN: KEN KESEY’S FORGOTTEN BOOK SERIES

Benito Vila·September 26, 2019

All Please Kill Me PostsBenito VilaBooksCool PeopleHistoryInterviews

1.4k

SHARES

Ken Kesey assembled his Merry Pranksters and other kindred spirits for one more, and final, prank—a semi-regular book series that contained pieces of his unfinished novel about his beloved grandmother, and contributions from a who’s who of the counterculture. Benito Vila gathered the 7 issues of the series—published over 20 years time—read them, then contacted Ed McClanahan, who edited the last volume, published after Kesey died in 2001, and Jeff Forrester, who was one of Kesey’s writing students. What ensued was a cosmic conversation worthy of Kesey’s ghost.

Prologue: Caution– Weird Read

After trading emails over a couple weeks in January, I call Zane Kesey to talk to him about his father, Ken, and about his own experience growing up Kesey. Zane picks up, I remind him why I’m calling, and I hear, “Yeah, I’ll do an interview with you, but not today.” I get ready to ask when would be good to call again when he says, “And I don’t know when will be good. You’ll have to keep calling. And be ready; one day will be the right one.”

Ah, the perfect Prankster commitment coming from a master of Prankster life. After all, this is Zane Kesey––the same Zane Kesey who in 1990 made off with the second Further, the sort-of-like-the-original-bus Ken Kesey was mischievously driving from Oregon to Washington, D.C. to present to the Smithsonian as being the original. Not having any of it, the younger Kesey instead drove the “new” bus home in the middle of a California night, out-pranking his dad by leaving a crime-scene-like chalked outline of the bus in its place, along with the words “Nothing Lasts”––artfully declaring Further was never meant to live in a museum.

Our brief conversation that day turned towards what Zane sells on his “official Ken Kesey site”––blotter acid art, Prankster-and-Further-themed DVDs, magnets, pins, posters, T-shirts, and his dad’s books––including Spit In The Ocean, an obscure 1974-to-1981 book series. Zane described Ken conceiving Spit––or SITO as it also became known––as having seven issues with each issue having its own theme and its own editor. When it became clear our talk was coming to a close, I ordered the six Spit issues Zane had on hand and went to Amazon to order Spit in the Ocean #7: All About Kesey. I had no idea what I was in for.

Spitologue: Kesey’s Game

Spit 7 arrived first, so I went at it, finding All About Kesey contains remembrances of Kesey by friends, neighbors and collaborators, including a who’s who of counterculture miscreants. In the collection are pieces by Hunter S. Thompson, Paul Krassner, George Walker, Rosalie Sorrels, Chloe Scott, Sterling Lord, Gus Van Sant and Kesey himself. Edited by novelist and long-time Kesey confederate Ed McClanahan, the book chronicles the development of the Spit series and then jumps into the spontaneous genius that attracted so many to Kesey and his way of doing things.

That way consistently expresses itself in a poke-fun humor that leads Kesey to steal into an apartment shared by Stewart Brand and Paul Krassner to cut-out-and-redraw the eyes in a Richard Nixon poster so that Nixon might more easily follow people around the room (Kesey left their Geronimo poster untouched). Kesey’s playful jester-jock-farmer-storyteller persona comes through in letters to friends and in his own accounts of the situations he found himself in. Spit 7 presents the next Kesey generation wondering aloud, “Who will teach us to hypnotize the chickens?” and Wavy Gravy cautioning everyone to, “Never trust a Prankster, even under ground.” The book closes with a set of Brother Kesey’s Words to the Wise, including “Fame is a wart”; “When you don’t know where you’re going, you have to stick together just in case someone gets there”, and, ultimately, “Nothing Lasts.”

It turns out the Spit series was first conceived by Kesey as a way to serialize an unpublished novel recounting the adventures or “prayers” of one Grandma Whittier. Who Grandma Whittier is remains obscure and open to interpretation––“She symbolizes a lot of things,” Kesey compatriot George Walker said last week, “but she’s mostly Ken’s Grandma Smith, who he was close to”. Kesey created six installments of the novel, each one closing out each of the first six editions of Spit before Grandma Smith passed on in the early 1980s.

In Spit 1, Kesey uses an Old English style to describe the structure of the series: “My game? each issue around gats a new wylde dealer and a new wylde dealer’s choice. And I, being first merrie, as I sayd, and, merrie, being first to chose, do chose to deal this opening hand about the common table, Age.” True to his word, in each of those first six editions, Kesey curates a discussion around a single topic, with his selected editors, writers and illustrators giving voice to––in Spit 1 through Spit 6––the aches of aging; the challenges of change; the search for higher intelligence; the insights of creative women; a mid-70s trip to the Pyramids and the life of Neal Cassady.

Nowhere, in any of the books, does Kesey describe the unruly literary card game he’s playing. Spit in the Ocean itself is a variety of poker, one in which each player is dealt four cards facedown and is left to combine those with a card dealt face-up––that faced card, and all others of the same rank, are then considered wild cards––leaving the player free to give those cards any conceivable value. The game is known to spark crazed emotions: in the film A Streetcar Named Desire, it’s after winning a hand of Spit in the Ocean that a drunken Stanley (Brando) gets up enraged, tosses a radio playing a tedious waltz through a window and then beats the perplexed Stella (Vivien Leigh)––all that soon leading to his standing in the street pleading “Stella!” at the top of his lungs.

Leave a comment