Victor Hugo Presco was not a good looking man, but he was well liked. As a professioanl gambler on the Barbary Coast, and in Crockett, he must have seemed like a dashing and romantic character to my grandmother. That is Melba walking with her handsome son in downtown Oakland – her Love Child?

Rosemary told me she tried to talk her husband into moving to Los Angeles and get into Motion Pictures.

“I don’t want to be around a bunch of phonies.” was Vic’s reply.

In the first chapter of The Sea Wolf Jack London presents intillectual arguments as to what constututes a man.

My best freind Bill Arnold and I had such conversations when we were thirteen, we both fans of Jack London and John Steinbeck. Bill was impressed that I ran into the kitchen, got a big butcher knife, and ordered my drunken father out of our house where he was ordered to keep away from by the court. He had not visitation rights. He had come to take Vicki on hundred mile drunken drive to his mother’s house, and he was weaving into our antique furniture. I was twelve. He came at me. I saw murder in my father’s eyes.

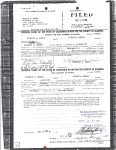

The father of the world famous artist, Rosamond, was born August 12, 1923: got married on September 17, 1944: got divorced February 17, 1960.

Jon Presco

Copyright 2011

The Barbary Coast was an outgrowth of Sydney-Town, the area at the foot of Broadway and Pacific Street formerly inhabited by the Australian immigrants known as Sydney Ducks. The area was already a hotbed of prostitution and vice by the time the Australian immigrants arrived. The neighborhood acquired its new name sometime around 1860 from the name of the coast of North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt) where Arab pirates attacked Mediterranean ships. The name Barbary is derived from the Berbers.

“The Barbary Coast is the haunt of the low and the vile of every kind. The petty thief, the house burglar, the tramp, the whoremonger, lewd women, cutthroats, murderers, all are found here. Dance-halls and concert-saloons, where blear-eyed men and faded women drink vile liquor, smoke offensive tobacco, engage in vulgar conduct, sing obscene songs and say and do everything to heap upon themselves more degradation, are numerous. Low gambling houses, thronged with riot-loving rowdies, in all stages of intoxication, are there. Opium dens, where heathen Chinese and God-forsaken men and women are sprawled in miscellaneous confusion, disgustingly drowsy or completely overcome, are there. Licentiousness, debauchery, pollution, loathsome disease, insanity from dissipation, misery, poverty, wealth, profanity, blasphemy, and death, are there. And Hell, yawning to receive the putrid mass, is there also.”[1]

Barbary Coast (1935) is a period film directed by Howard Hawks. Shot in black-and-white and set in San Francisco during the Gold Rush era, the film combines elements of crime, Western, melodrama and adventure genres, features a wide range of actors, from good-guy Joel McCrea to bad-boy Edward G. Robinson, and stars Miriam Hopkins in the leading role as Mary ‘Swan’ Rutledge.

On a foggy night in 1850, Mary Rutledge (Hopkins), accompanied by retired Colonel Marcus Aurelius Cobb (Frank Craven), arrives in San Francisco Bay from New York aboard the Flying Cloud. A gold digger of the other kind, she has come to wed the wealthy owner of a local saloon. The men at the wharf are more than happy to greet the ‘white woman,'[1] but reluctant to inform her that her fiancé is dead, murdered most likely by a certain Louis Chamalis (Robinson), the powerful owner of another Barbary Coast establishment, the Bella Donna restaurant and gambling house. Mary is at first quite upset, but quickly pulls herself together and asks the way to the Bella Donna, with a look of ambition on her face.

Mary meets Chamalis and quickly agrees to be his companion, not only for economic reasons (as an attraction, she helps draw in customers), but for personal pleasure as well. Chamalis gives her the name ‘Swan’ and she becomes more or less his female escort. She accompanies him on promenades in town (the ‘sinful’ unwed couple is insulted in one scene by the mayor’s wife) and he showers her with extravagant gifts. Their relationship sours rather quickly, however, and Swan is angered by some of Chamalis’s destructive power-mongering. She does not, however, mind running a crooked roulette wheel and cheating the miners out of their gold.

Chapter 1

I scarcely know where to begin, though I sometimes facetiously place the cause of it all to Charley Furuseth’s credit. He kept a summer cottage in Mill Valley, under the shadow of Mount Tamalpais, and never occupied it except when he loafed through the winter months and read Nietzsche and Schopenhauer to rest his brain. When summer came on, he elected to sweat out a hot and dusty existence in the city and to toil incessantly. Had it not been my custom to run up to see him every Saturday afternoon and to stop over till Monday morning, this particular January Monday morning would not have found me afloat on San Francisco Bay.

Not but that I was afloat in a safe craft, for the Martinez was a new ferry-steamer, making her fourth or fifth trip on the run between Sausalito and San Francisco. The danger lay in the heavy fog which blanketed the bay, and of which, as a landsman, I had little apprehension. In fact, I remember the placid exaltation with which took up my position on the forward upper deck, directly beneath the pilot-house, and allowed the mystery of the fog to lay hold of my imagination. A fresh breeze was blowing, and for a time I was alone in the moist obscurity; yet not alone, for I was dimly conscious of the presence of the pilot, and of what I took to be the captain, in the glass house above my head.

I remember thinking how comfortable it was, this division of labor which made it unnecessary for me to study fogs, winds, tides, and navigation, in order to visit my friend who lived across an arm of the sea. It was good that men should be specialists, I mused. The peculiar knowledge of the pilot and captain sufficed for many thousands of people who knew no more of the sea and navigation than I knew. On the other hand, instead of having to devote my energy to the learning of a multitude of things, I concentrated it upon a few particular things, such as, for instance, the analysis of Poe’s place in American literature, an essay of mine, by the way, in the current Atlantic. Coming aboard, as I passed through the cabin, I had noticed with greedy eyes a stout gentleman reading the Atlantic, which was open at my very essay. And there it was again, the division of labor, the special knowledge of the pilot and captain which permitted the stout gentleman to read my special knowledge on Poe while they carried him safely from Sausalito to San Francisco.

A red-faced man, slamming the cabin door behind him and stumping out on the deck, interrupted my reflections, though I made a mental note of the topic for use in a projected essay which I had thought of calling “The Necessity for Freedom: A Plea for the Artist.” The red-faced man shot a glance up at the pilot-house, gazed around at the fog, stumped across the deck and back (he evidently had artificial legs), and stood still by my side, legs wide apart, and with an expression of keen enjoyment on his face. I was not wrong when decided that his days had been spent on the sea.

“It’s nasty weather like this here that turns heads gray before their time,” he said, with a nod toward the pilot-house.

“I had not thought there was any particular strain,” answered. “It seems as simple as A, B, C. They know the direction by compass, the distance, and the speed. I should not call it anything more than mathematical certainty.”

“Strain!” he snorted. “Simple as A, B, C! Mathematical certainty!”

He seemed to brace himself up and lean backward against the air as he stared at me. “How about this here tide that’s rushin’ out through the Golden Gate?” he demanded, or bellowed, rather. “How fast is she ebbin’? What’s the drift, eh? Listen to that, will you? A bell-buoy, and we’re a-top of it! See ’em alterin’ the course!”

From out of the fog came the mournful tolling of a bell, and could see the pilot turning the wheel with great rapidity. The bell, which had seemed straight ahead, was now sounding from the side. Our own whistle was blowing hoarsely, and from time to time the sound of other whistles came to us from out of the fog.

http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/jlondon/bl-jlon-sea-1.htm

Leave a comment