The California Kid

by

John Presco

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

On the morning of May 11, 2025, I John Presco read this…

“By the early 1860s, Fort Alcatraz was housing confederate prisoners of war as well as private citizens accused of treason or being confederate sympathizers after the suspension of habeas corpus. The number of prisoners in Fort Alcatraz climbed steadily through the Civil War and additional cells were constructed as the island facility transitioned into a long-term military prison in 1868.:

“citizens accused of treason or being confederate sympathizers after the suspension of habeas corpus.”

The biggest story today is whether the President will suspence the right of habeas corpus. I wonder of Trump, and his Neo-Confederate supporter want to lock up the Pelosi and Newsom families on Alcatraz, that was once called “Fremont Island”. Today, my families battle for Alcatraz, commences. As does the battle for my grandson, Tyler Hunt, who was rested friom me by a radical Tea Party family – whose son could not sire a child! His seed was no good. They were pretty poround of their white history, until they saw my family history. They wanted my history, Then set out to own it via my daughter, Heather Hanson. Via a marriage cirtificate, they tried to capture the Benton-Fremont tree, They failed.

This morning I found evidence Fremont did not own Alcatraz, but, tried to own it through legal deception, and outright fraud. Is this evidence – conclusive? I am seeking an attorney in order to force the United States Governor pay me and my family $7,000,000 million dollars, which is the inflation value of $500,000 dollars. I keep the Copyright to my family story, titled ‘The California Kid’, This should have been Fremont’s moniker, but in the last few days I found a confederacy of Pro-Slavery “knights” who came West to subvert Fremont’s claims, and destroy the Bear Flag Rebellion. When these Knights discovered Fremont was prepared to sell California to Prussia, and creat a New Nation in the West that would enter the Civil War on the side of the Union, the Cartel did all they could to destory the Benton-Fremont family, and make Calfornia a Slave State member of the Confederacy,

Above is a photograph of me taking Tyler for a stroll in his stroller. Here is the historic-fiction I began November 21, 2021. Need I say, again I am…a prophet? A California Prophet!……know as…..

THE CALIFORNIA KID!

Opening Scene: Oakpatch. Johnny Oakland stands on his balcony and points to Alcatraz Island.

“I’ll own that island, one day! And Belmont! They dug up my Janke grandparents, the founders of Belmont, and threw them in a hole in Redwood City. Nothing good came our of that town! Soon, I will have my revenge. If my name isn’t The California Kid, I will be the Mayor of Belmont – and the Governor of Fremont Island!”

Rollins may be released from San Quentin, but he is still imprisoned in an ambivalent relationship with the wife he thinks betrayed him (Joanne Dru).

WASHINGTON (AP) — White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller says President Donald Trump‘s administration is looking for ways to expand its legal power to deport migrants who are in the United States illegally. To achieve that, he says the administration is “actively looking at” suspending habeas corpus, the constitutional right for people to legally challenge their detention by the government.

Such a move would be aimed at migrants as part of the Republican president’s broader crackdown at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“The Constitution is clear, and that of course is the supreme law of the land, that the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus can be suspended in a time of invasion,” Miller told reporters outside the White House on Friday.

“So, I would say that’s an option we’re actively looking at,” Miller said. “Look, a lot of it depends on whether the courts do the right thing or not.”

The Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, 12 Stat. 755 (1863), entitled An Act relating to Habeas Corpus, and regulating Judicial Proceedings in Certain Cases, was an Act of Congress that authorized the president of the United States to suspend the right of habeas corpus in response to the American Civil War and provided for the release of political prisoners. It began in the House of Representatives as an indemnity bill, introduced on December 5, 1862, releasing the president and his subordinates from any liability for having suspended habeas corpus without congressional approval.[1] The Senate amended the House’s bill,[2] and the compromise reported out of the conference committee altered it to qualify the indemnity and to suspend habeas corpus on Congress’s own authority.[3] Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law on March 3, 1863, and suspended habeas corpus under the authority it granted him six months later. The suspension was partially lifted with the issuance of Proclamation 148 by Andrew Johnson,[4] and the Act became inoperative with the end of the Civil War.[citation needed] The exceptions to Johnson’s Proclamation 148 were the States of Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas, the District of Columbia, and the Territories of New Mexico and Arizona.

Buying power of $500,000 in 1800

This chart shows a calculation of buying power equivalence for $500,000 in 1800 (price index tracking began in 1635).

For example, if you started with $500,000, you would need to end with $12,690,436.51 in order to “adjust” for inflation (sometimes refered to as “beating inflation”).

Alcatraz Island and the Workman and Temple Families, Part Two

- by homesteadmuseum

- Posted on

by Paul R. Spitzzeri

If President Millard Fillmore’s executive order of December 1850 stipulating that Alcatraz Island, along with other California parcels, was government property was truly the last word about the legal status of the island, this post would have been limited to yesterday’s part one.

But, over five years later, a newspaper article appeared in the Los Angeles Star that caught the eye of F.P.F. Temple, who executed an agreement in early March 1847 with U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont to sell the island for $5,000 with the proviso that the federal government would approve the deal.

Not only did this not happen, but Frémont was court-martialed later that year for a number of reasons, including the Alcatraz arrangement. With Fillmore’s order, the matter would appear to have been over, except that Frémont, characteristically, was not done with the issue.

The Star notice of 23 February 1856 was simple:

Palmer, Cook, and Co. have commenced suit against the U.S. authorities for the recovery of Alcatraz Island, upon which fortifications to the value of $500,000 have been erected. It appears that Palmer, Cook, and Co., purchased the Island of Fremont, Fremont from a Mr. Temple, Mr. Temple from Julian Workman, who obtained it from Pio Pico.

At least this brief reporting was correct in terms of the island’s chain of ownership, as opposed to federal documents which stated that Temple was given the grant to the island from Pico, rather than his father-in-law Workman. Also noteworthy is the statement about the expenditure of a half million dollars to fortify the island for military purposes. This week’s reporting of archaeological work on the island mentions that Civil War-era remnants of tunnels and structures at Alcatraz were unearthed, but there were prior fortifications there as the 1856 article shows.

The situation involving the San Francisco banking firm of Palmer, Cook and Company and Frémont is complicated, but there was a court action in early February that led to a Sheriff’s sale of Frémont’s interest in Alcatraz being auctioned for $200 to Edward Jones, who received a certificate of the sale and then handed it over to William H. Palmer. This may have been part of a larger scheme involving Frémont and the firm who had such close ties that, when Frémont was the first Republican candidate for president later in the year, it was believed the bank would benefit from their connections to him, though Frémont lost to Democrat James Buchanan.

Temple did not wait long to respond to the news he read in the Star. On 4 March, he penned a letter to either three men or to one, depending on the source. A transcription of the missive made by Temple’s son, John, had the names N. Callahan, John G. Downey, and V.E. Howard, while a typed transcript, likely provided by John H. Temple to an attorney, simply had the addressee as “Howard, Esq., San Francisco.”

The identity of Callahan has not been determined, but John G. Downey (1827-1894) was a native of Ireland who came to the United States in his teens, living in Baltimore with family before he was apprenticed to a druggist in Washington, D.C.. He practiced that trade in Vicksburg, Mississippi and Cincinnati, where, at the latter, he had a drug store with a partner.

With the onset of the Gold Rush, Downey sold out his share in the business and headed to California. As for so many, prospecting yielded little, so Downey went to work for a wholesale drug company in San Francisco and dabbled as a money lender. At the end of 1850, he bought a cache of drugs and medicines and shipped them to Los Angeles, where he was advised to go by James P. McFarland who became his partner in the City of Angels, opening the first drug store in the town.

The business operated for just a couple of years when it was sold, but, by then, Downey, who’d become a naturalized American citizen in 1851, entered local politics, serving on the Los Angeles Common [City] Council and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. He was serving on the latter when Temple wrote his letter, but in September 1856 won election to the California Assembly.

In February 1852, Downey married María Jesús Guirado, whose family had a ranch in modern Whittier, though they two were childless, and that relationship would help with his future activities in real estate. This included joining Phineas Banning, Benjamin D. Wilson and others in buying part of Rancho San Pedro for a new port and town, which became Wilmington. Then, with McFarland, he foreclosed on Rancho Santa Gertrudes, whose insolvent owner, Lemuel Carpenter, killed himself as a result. On this land, Downey later subdivided his namesake town.

Volney E. Howard (1809-1889) is a remarkable figure. Born in Maine, he went to Mississippi in his early twenties to join an uncle in a law practice, but arrived to find the elder Howard died weeks before. He went ahead and was admitted to the bar and opened a practice, but he also ran a newspaper and was elected to the state legislature. Howard was, for several years, the reporter of the Mississippi Supreme Court and, in 1840, ran for governor, though he lost. After a controversy over the state’s role in a bank led to a duel in which Howard was wounded, he left for Texas, then readying for admittance into the Union.

He’d been at San Antonio for just a short time when he was elected to the convention that drafted the Texas state constitution. Resuming a law practice, which was successful, he also secured election to the House of Representatives, serving in Congress from 1850 to 1853 and resigning his seat when he was named federal attorney for land claims cases in California stemming from an act of Congress passed in March 1851. Howard came out to San Francisco and was later joined by his wife Catherine, and their many children, including sons who became lawyers.

Dissatisfied with the position, however, Howard soon resigned and opened up another law practice, specializing in land titles. One client was William Workman, specifically for a claim for the lands of the secularized Mission San Gabriel, the deed of which Workman and Hugo Reid received in 1846 at the time the Alcatraz grant was made by Governor Pío Pico.

Later in 1856, Howard got into difficulties as serious as the one that led him to flee Mississippi. A vigilance committee formed in San Francisco, ostensibly because of high crime but which also took on political dimensions that led to martial law. After Governor J. Neely Johnson ordered the committee to disband and was ignored, he appointed Howard, a vocal opponent of the vigilantes, a militia general, but he was unable to end the vigilante regime. Howard left for Sacramento and later lived in Oakland and briefly returned to San Francisco, though his anti-vigilante past was held against him and he moved south, settling in San Gabriel in 1861.

Howard raised oranges, practiced law and later was Los Angeles County District Attorney and a member of the 1879 convention that rewrote California’s constitution. He served a term as Superior Court Judge, when that new level of court was created in 1879, and then retired. He kept his residence at San Gabriel, but declining health led him to Santa Monica where he died.

Temple’s letter, apparently directed primarily to Howard because of the attorney’s extensive experience with land cases, stated that he’d noticed the article in the Star and added:

for my part, I cannot see the least shadow of right Fremont had to dispose of the island . . . Alcatras Island was granted to my father-in-law, Mr. W. Workman, in the spring or early in the summer of 1846 by Don Pio Pico, then Governor of California. A few months afterwards Mr. Workman transferred to me the original documents with a deed from him. Then Col. J.C. Fremont was in this place in 1847. I sold him the Island in the name of the U.S. (not to him as a private individual) for the sum of Five Thousand Dollars for which he gave me his bond in the name of the U.S., said amount on any part of it has never been paid (at which time I gave him the original title and transfer.

Temple went on to note that when Fremont was court-martialed the purchase was disallowed by the federal government, but now he tried to claim the island “without the slightest ground in justice.” Given the circumstances, Temple told Howard “I consider my claim to the Island still good” and asked the attorney to “examine into the merits of the case” and if recovery for Temple seemed feasible, “I will give you fifteen per cent interest in the claim, if you feel disposed to attend to the business without any further expense on my part.”

He concluded that “the Island is very valuable, and I am confident if my claim is presented Palmer Cook and Co. will have no show whatever to recover the island. By examining Fremont’s trial, I think you will see a copy of the bond he gave me.”

Notably, John H. Temple wrote, decades later, some notes concerning Alcatraz, stating that on 20 April 1848, his father “endorsed Gov. Fremont’s bond in favor of Capt. William D. Phelps which said captain took to Washington to collect . . . [but] it was not collected,” as documented in a letter F.P.F. wrote to his brother Abraham, that September. Phelps, incidentally, was captain of the bark Tasso, which brought F.P.F. Temple to California from Boston seven years before.

We’ll pick up the story soon with part three of this post, so check back for the continuation of this fascinating story!

The Captivating History of Alcatraz Island: From Military Fort to National Historic Landmark

By Javier Fernandez

Overlooking the San Francisco Bay, Alcatraz Island has captured the public’s imagination for generations, often serving as the setting for books and movies. Better known for its past as a federal prison, housing the nation’s most notorious criminals and troublesome inmates, Alcatraz Island has a rich history which also includes its function as a military fort, the site of a civil protest occupation, a GSA managed asset and a National Historic Landmark.

Located 1.25 miles offshore from the city of San Francisco, Alcatraz Island received its name from Spanish naval officer Juan Manuel de Ayala y Aranza in 1775 while charting the San Francisco Bay. Ayala named the island using a now archaic Spanish word for pelicans which translates to “La Isla de los Alcatraces” or “The Island of the Pelicans”. Control of the island shifted to Mexico following the country’s successful war of independence against Spain in 1821, and lastly to the U.S. following the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

Fort Alcatraz

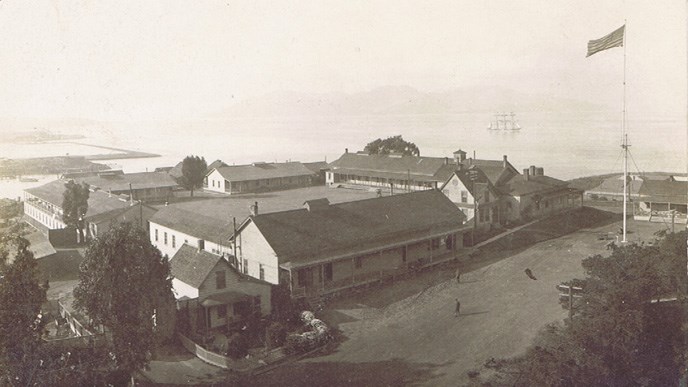

Following the Mexican-American War, President Milliard Fillmore recognized the island’s strategic military value and ordered Alcatraz Island to be set aside as a military reservation. Construction of Fort Alcatraz was completed in 1858.

By the early 1860s, Fort Alcatraz was housing confederate prisoners of war as well as private citizens accused of treason or being confederate sympathizers after the suspension of habeas corpus. The number of prisoners in Fort Alcatraz climbed steadily through the Civil War and additional cells were constructed as the island facility transitioned into a long-term military prison in 1868.

Men of the 13th infantry on Alcatraz Island circa 1902. – Courtesy NPS Archive

Military Prison

Alcatraz Island’s geographic location in the middle of San Francisco Bay made it uniquely suited to serve as a prison. The bay’s strong sea currents and frigid waters would prove deadly for escapees. After the end of the Civil War, the prisoner demographics grew to include Native American prisoners from the Indian Wars.

Development and construction on the island would continue through the 1880s to accommodate a growing prisoner population that had ballooned to over 450 during the Spanish-American War. The prison cells’ wooden construction was vulnerable to fires and after multiple incidents, they were replaced by longer-lasting and less vulnerable concrete structures; a trend which continued through the 1930s.

The prison was not seriously impacted by the 1906 earthquake which ravaged the city. Alcatraz temporarily housed prisoners from the city whose quarters were destroyed by the quake. It was also around this time that the island’s military defense operations ceased completely and shifted entirely to operational functions as a U.S. military prison. Between 1910 and 1912, the prison was entirely rebuilt in concrete by prisoners at a cost of $250,000. The new prison was renamed as “the Pacific Branch, U.S. Disciplinary Barracks for the U.S. Army” or more popularly known as “The Rock” by those who worked or were incarcerated there.

Federal Penitentiary

Alcatraz inmates entering the mess hall, 1954 – Courtesy NPS Archives

In 1933, the U.S. War Department determined that the Alcatraz military prison was no longer needed for defense purposes and transferred the facility to the Federal Bureau of Prisons the following year. In August 1934, the island prison was modernized and fortified, leading prison officials to declare Alcatraz America’s strongest prison and the ideal place to house the nation’s most ruthless and notorious criminals. Bank robbers, kidnappers, mobsters and murderers including Al Capone, Robert Franklin Stroud, better known as “the Birdman of Alcatraz”, and George “Machinegun” Kelly all served time on the island.

In total, 36 prisoners attempted to escape the island prison; 23 were captured alive, six were shot dead, two drowned, and five were officially listed as “missing and presumed drowned”. In 1962, the only successful escape occurred when John Paul Scott succeeded in swimming to the shore. He was quickly apprehended when four teenagers found the fugitive unconscious and hypothermic at Fort Point beneath the Golden Gate Bridge.

By the late 1950s, the high operational and maintenance costs of running the island prison were making the Bureau of Prisons question the long term viability of Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary. A 1959 report stated that Alcatraz cost three times as much to operate than a comparable prison; it cost $10 per prisoner per day compared to $3 in other prisons. Continuous exposure to salt spray contributed heavily to the prison’s structural deterioration and engineers determined it would cost $5 million to repair the damage. Ultimately, these underlying costs led to the closure of Alcatraz on March 21, 1963.

GSA’s Role and Native American Occupation

Robert Robertson, Executive Director of the Vice President’s National Council on Indian Opportunity, and Thomas Hannon, Regional Administrator of the General Services Administration, meet with the island’s occupants in January 1970.

The Department of Justice declared Alcatraz Island to be excess federal property on April 12, 1963, and a presidential committee was formed to determine the island’s future use. At a March 1964 meeting, five Sioux Indians filed a claim for Alcatraz citing the right of tribes to claim excess government lands in a hope to transform the former prison into a university focused on Native American Studies and an American Indian Museum.

Later that month, the U.S. Attorney dismissed the group’s claim as being without foundation and GSA assumed custody of Alcatraz Island in July 1964. Following the City of San Francisco’s stated interest in turning Alcatraz Island into a recreational park site, GSA issued the Department of Interior a December 1969 deadline to explore the site as a federal recreation area.

A group of Native American activists, composed mainly of college students, occupied Alcatraz island on November 20, 1969. The group, who called themselves the “United Indians of All Tribes”, rejected orders to leave Alcatraz Island.

Upon learning of the activists occupying Alcatraz, GSA Region 9 Regional Administrator Thomas Hannon traveled to the island to initiate “peaceable” talks with the activist group. The aim was to find an “amicable solution” and reassure the group that there would be no forceful confrontation. Regional Administrator Hannon’s involvement with the activists came to an end when then President Nixon tapped Leonard Garment, special advisor to the president for minority affairs, and his assistant to take over negotiations.

By Christmas 1969, approximately 200 Native Americans occupied Alcatraz Island. The group suffered numerous mishaps including the tragic death of the group leader’s 13-year-old daughter and an accidental fire that destroyed numerous buildings, including the warden’s home, lighthouse keepers’ house, and Coast Guard quarters. Nineteen grueling months of struggles took its toll, and slowly activist occupiers began to desert the island. On June 11, 1971, federal agents landed on Alcatraz Island and removed the last 15 people remaining.

While the occupation proved unsuccessful, many historians now view their efforts as a watershed moment for Native American activism. The effort led the U.S. government to deed hundreds of acres of federal land in Yolo County to Native Americans, and Mexican Americans founded Deganawidah-Quetzalcoatl University in 1971.

Ranger Ruth Lawrence with a group of youth in Alcatraz cell block, c. 1979. – Courtesy NPS Archive

National Historic Landmark

In 1972, President Richard Nixon signed legislation to establish the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, allocating $120 million for the

acquisition and development of the land. GSA facilitated the transfer of Alcatraz Island and Fort Mason from the U.S. Army to the National Park Service. Alcatraz Island was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

Today, Alcatraz Island ranks as one of the National Park Service’s most popular tourist attractions with over 1.4 million visitors annually. As we celebrate National Historic Preservation Month, we can appreciate that Alcatraz remains accessible to the public and will continue to be accessible to future generations.

Gold War

Posted on November 14, 2021 by Royal Rosamond Press

Gold War

An idea for a movie or series by

John Presco

Copyright 2021

Mark Twain offered Thomas Starr King and Herman Melville one of his Cuban cigars to go with their mint julip that Jessie Benton Fremont made for them and the other guests of her salon that she held at her new home in Black Point. Jessie had just introduced Brett Harte, when the conversation digressed to the scuttlebutt over the idea of General Fremont forming a nation in the west now that it was certain the South would secede from the Union. The garrison at Fort Sumpter was put on alert. With the reports coming in that a very large vein of gold was lying thirty feet under the San Joaquin River, and perhaps the whole valley cradled the largest gold deposit in the world, powerful and wealthy men were meeting with John behind closed doors. They wanted him – to grab the gold!

“Scientists are concluding a series of glaciers scraped the gold from the Sierra Foothills as they melted, and lay down a river of gold in the valley. If we don’t grab it, Napoleon may invade from Mexico – with the help of the Hapsburgs.” offered Starr, as he waved off Twain’s cigar. “I don’t smoke!”

“What is that?” Melville asked, as he saw puffs of smoke come through the haze that lingered at the Golden Gate. Then came the booms of canon.

“What the hell!” exclaimed Twain, and ran inside to get a spyglass. He emerged with General Fremont. Together they focussed on the warships that came sailing out of the mist, all cannons firing on the small fortification at the point.

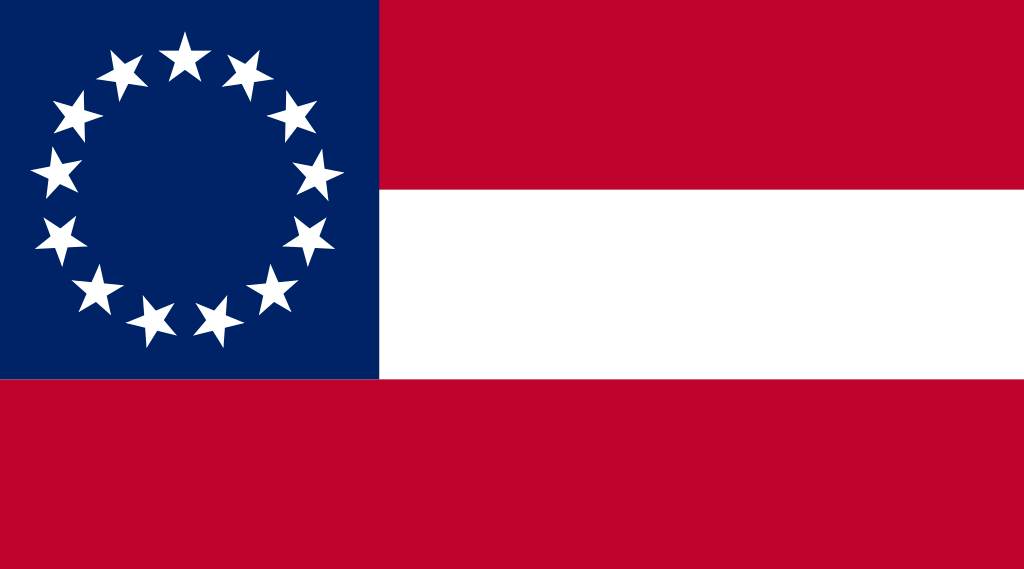

“They’re flying the new flag of the Confederacy!” cried the General.

“Look! There fly the flag of Napoleon!” shouted Melville!

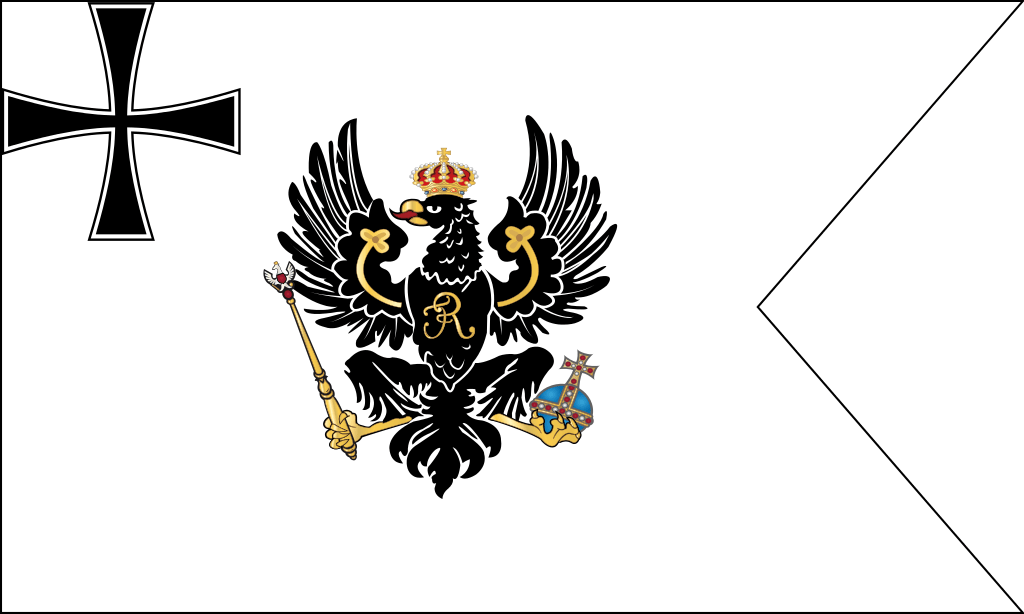

“To arms!” cried Mr. Harte, and he was given a look that went around world. At the exact same time a Prussian fleet sailed out of port in Chile. There were three frigates, and five troop transports. But what got the attention of the German colonizers, and the Native Americans, was the sight to the four ironclads that belched smoke and steam.

“Laviathans!”

Prussia had made an offer to purchase California, but the discovery of gold, and the Gold Rush, forced the military kingdom that threatened Europe, to back out the deal. But, the Prussian Royalty had a plan. Timing is everything. When Wilhelm got news of – The Firing On Fort Mason – his fleet was sighted by the citizens of Los Angeles. Many of them were German immigrants. On cue, they formed militias, and would march into the San Joaquin Valley from the South!

‘When Senator Thomas Hart Benton was informed the South had landed an army in Oakland, he told his men to send the Ozark Brigade to Oregon to meet the British force he knew would come down from Canada to fight their old foe, the Scott-Irish. There were Germans from Saint Louis in this bunch.

“Gentleman! The Gold War….has begun!”

__________________________________

Author’s Notes

Jessie Fremont ins Sunshine Magazine said the British had plans to take over the San Joaquin Valley and move tens of thousands of Irish Catholics there. Prussian offered six million dollars for California. Radical German Forty-Eighters put Lincoln in office. Lincoln put tens of thousands of Abolitionist German Immigrants in Freemont’s ‘Mountain Department’ with no Confederate army anywhere near. Did Lincoln fear the Turner Germans would throw Lincoln out of office in a coup, because he kept putting off Emancipating the slaves? Did Joseph Lane have plans to make Oregon a slave slate – and California? Did Blair have a plan to make peace with the Southern slave owners by offering them the West, and ending slavery in the Original Thirteen Colonies? The British may have promised to thwart this idea because they were putting an end to slavery all over the world.

An hour ago I read an article by Joe Ryan who asks the questions I have been asking for ten years – at least! I have wondered if my great grandfather, Carl Janke, was part of a Prussian plan to colonize California – without a purchase. Just start moving in Germans from all over the world. Much of the world’s cotton is grown in the San Joachim Valley. How close did we come to having poor Irish Catholics being the Cotton Picker of The World…Cotton Mundi. Protestant England is free of the Pope – alas! Remember Drake and the sinking of the Spanish Armada that was built with New World gold.

Mankind’s love of gold……will be with us forever!

John Presco

President: Royal Rosamond Press

Understanding General John Fremont (joeryancivilwar.com)

In the process, harking back to Frémont’s glory days as the Pathfinder, Lincoln created the “Mountain Department” and sent Frémont on an illusionary mission to nowhere, conveniently stashing on the perimeter of Virginia territory thirty thousand men. It appears that most of these men were Germans, many of whom spoke no English. Whether this fact has something to do with Lincoln’s thinking here, who knows?

Flags of the Confederate States of America – Wikipedia

The Prussian Navy was created in 1701 from the former Brandenburg Navy upon the dissolution of Brandenburg-Prussia, the personal union of Brandenburg and Prussia under the House of Hohenzollern, after the elevation of Frederick I from Duke of Prussia to King in Prussia. The Prussian Navy fought in several wars but was active mainly as a merchant navy throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as Prussia’s military consistently concentrated on the Prussian Army. The Prussian Navy was dissolved in 1867 when Prussia joined the North German Confederation, and its naval forces were absorbed into the North German Federal Navy.

The naval preference of the last Prussian king, German Emperor Wilhelm II, prepared the end of the Prussian monarchy. The German naval buildup of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was one of the causes of World War I; and it was the mutinying sailors of the High Seas Fleet who forced the abdication of the Emperor during the German Revolution of 1918–1919. The Navy continued as the Reichsmarine (Reich Navy) and later the Kriegsmarine (War Navy), until at the end of World War II, it faced its own end.

Between the mid-1860s and the early 1880s, the Prussian and later Imperial German Navies purchased or built sixteen ironclad warships.[1][a] In 1860, however, the Prussian Navy consisted solely of wooden, unarmored warships. The following year, Prince Adalbert and Albrecht von Roon wrote an expanded fleet plan that included four large ironclads and four smaller ironclads. Two of the latter were to be ordered from Britain immediately,[8]

Confederate States Navy – Wikipedia

List of ironclad warships of Germany – Wikipedia

Civil War at Fort Mason

Understanding John Fremont

By: Joe Ryan

Share this:

The Captivating History of Alcatraz Island: From Military Fort to National Historic Landmark

By Javier Fernandez

Overlooking the San Francisco Bay, Alcatraz Island has captured the public’s imagination for generations, often serving as the setting for books and movies. Better known for its past as a federal prison, housing the nation’s most notorious criminals and troublesome inmates, Alcatraz Island has a rich history which also includes its function as a military fort, the site of a civil protest occupation, a GSA managed asset and a National Historic Landmark.

Located 1.25 miles offshore from the city of San Francisco, Alcatraz Island received its name from Spanish naval officer Juan Manuel de Ayala y Aranza in 1775 while charting the San Francisco Bay. Ayala named the island using a now archaic Spanish word for pelicans which translates to “La Isla de los Alcatraces” or “The Island of the Pelicans”. Control of the island shifted to Mexico following the country’s successful war of independence against Spain in 1821, and lastly to the U.S. following the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

Fort Alcatraz

Following the Mexican-American War, President Milliard Fillmore recognized the island’s strategic military value and ordered Alcatraz Island to be set aside as a military reservation. Construction of Fort Alcatraz was completed in 1858.

By the early 1860s, Fort Alcatraz was housing confederate prisoners of war as well as private citizens accused of treason or being confederate sympathizers after the suspension of habeas corpus. The number of prisoners in Fort Alcatraz climbed steadily through the Civil War and additional cells were constructed as the island facility transitioned into a long-term military prison in 1868.

Men of the 13th infantry on Alcatraz Island circa 1902. – Courtesy NPS Archive

Military Prison

Alcatraz Island’s geographic location in the middle of San Francisco Bay made it uniquely suited to serve as a prison. The bay’s strong sea currents and frigid waters would prove deadly for escapees. After the end of the Civil War, the prisoner demographics grew to include Native American prisoners from the Indian Wars.

Development and construction on the island would continue through the 1880s to accommodate a growing prisoner population that had ballooned to over 450 during the Spanish-American War. The prison cells’ wooden construction was vulnerable to fires and after multiple incidents, they were replaced by longer-lasting and less vulnerable concrete structures; a trend which continued through the 1930s.

The prison was not seriously impacted by the 1906 earthquake which ravaged the city. Alcatraz temporarily housed prisoners from the city whose quarters were destroyed by the quake. It was also around this time that the island’s military defense operations ceased completely and shifted entirely to operational functions as a U.S. military prison. Between 1910 and 1912, the prison was entirely rebuilt in concrete by prisoners at a cost of $250,000. The new prison was renamed as “the Pacific Branch, U.S. Disciplinary Barracks for the U.S. Army” or more popularly known as “The Rock” by those who worked or were incarcerated there.

Federal Penitentiary

Alcatraz inmates entering the mess hall, 1954 – Courtesy NPS Archives

In 1933, the U.S. War Department determined that the Alcatraz military prison was no longer needed for defense purposes and transferred the facility to the Federal Bureau of Prisons the following year. In August 1934, the island prison was modernized and fortified, leading prison officials to declare Alcatraz America’s strongest prison and the ideal place to house the nation’s most ruthless and notorious criminals. Bank robbers, kidnappers, mobsters and murderers including Al Capone, Robert Franklin Stroud, better known as “the Birdman of Alcatraz”, and George “Machinegun” Kelly all served time on the island.

In total, 36 prisoners attempted to escape the island prison; 23 were captured alive, six were shot dead, two drowned, and five were officially listed as “missing and presumed drowned”. In 1962, the only successful escape occurred when John Paul Scott succeeded in swimming to the shore. He was quickly apprehended when four teenagers found the fugitive unconscious and hypothermic at Fort Point beneath the Golden Gate Bridge.

By the late 1950s, the high operational and maintenance costs of running the island prison were making the Bureau of Prisons question the long term viability of Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary. A 1959 report stated that Alcatraz cost three times as much to operate than a comparable prison; it cost $10 per prisoner per day compared to $3 in other prisons. Continuous exposure to salt spray contributed heavily to the prison’s structural deterioration and engineers determined it would cost $5 million to repair the damage. Ultimately, these underlying costs led to the closure of Alcatraz on March 21, 1963.

GSA’s Role and Native American Occupation

Robert Robertson, Executive Director of the Vice President’s National Council on Indian Opportunity, and Thomas Hannon, Regional Administrator of the General Services Administration, meet with the island’s occupants in January 1970.

The Department of Justice declared Alcatraz Island to be excess federal property on April 12, 1963, and a presidential committee was formed to determine the island’s future use. At a March 1964 meeting, five Sioux Indians filed a claim for Alcatraz citing the right of tribes to claim excess government lands in a hope to transform the former prison into a university focused on Native American Studies and an American Indian Museum.

Later that month, the U.S. Attorney dismissed the group’s claim as being without foundation and GSA assumed custody of Alcatraz Island in July 1964. Following the City of San Francisco’s stated interest in turning Alcatraz Island into a recreational park site, GSA issued the Department of Interior a December 1969 deadline to explore the site as a federal recreation area.

A group of Native American activists, composed mainly of college students, occupied Alcatraz island on November 20, 1969. The group, who called themselves the “United Indians of All Tribes”, rejected orders to leave Alcatraz Island.

Upon learning of the activists occupying Alcatraz, GSA Region 9 Regional Administrator Thomas Hannon traveled to the island to initiate “peaceable” talks with the activist group. The aim was to find an “amicable solution” and reassure the group that there would be no forceful confrontation. Regional Administrator Hannon’s involvement with the activists came to an end when then President Nixon tapped Leonard Garment, special advisor to the president for minority affairs, and his assistant to take over negotiations.

By Christmas 1969, approximately 200 Native Americans occupied Alcatraz Island. The group suffered numerous mishaps including the tragic death of the group leader’s 13-year-old daughter and an accidental fire that destroyed numerous buildings, including the warden’s home, lighthouse keepers’ house, and Coast Guard quarters. Nineteen grueling months of struggles took its toll, and slowly activist occupiers began to desert the island. On June 11, 1971, federal agents landed on Alcatraz Island and removed the last 15 people remaining.

While the occupation proved unsuccessful, many historians now view their efforts as a watershed moment for Native American activism. The effort led the U.S. government to deed hundreds of acres of federal land in Yolo County to Native Americans, and Mexican Americans founded Deganawidah-Quetzalcoatl University in 1971.

Ranger Ruth Lawrence with a group of youth in Alcatraz cell block, c. 1979. – Courtesy NPS Archive

National Historic Landmark

In 1972, President Richard Nixon signed legislation to establish the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, allocating $120 million for the

acquisition and development of the land. GSA facilitated the transfer of Alcatraz Island and Fort Mason from the U.S. Army to the National Park Service. Alcatraz Island was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

Today, Alcatraz Island ranks as one of the National Park Service’s most popular tourist attractions with over 1.4 million visitors annually. As we celebrate National Historic Preservation Month, we can appreciate that Alcatraz remains accessible to the public and will continue to be accessible to future generations.

Hell on Frisco Bay (1955)

Date: July 17, 2023Author: mikestakeonthemovies6 Comments

“I want trouble. I need it.”

One could honestly say that this Warner Bros. mid fifties gangster film feels like the studio recycled an old George Raft script from the late thirties and I wouldn’t disagree. Still, that doesn’t stop it from being a rugged gangland tale that offers up Alan Ladd in one if his best tough guy performances from the latter part of his career. To top it off the studio or perhaps Ladd’s own production company, Jaguar, who had a hand in the film have cast Johnny Rocco himself, Edward G. Robinson, as the tough talking hood that Ladd is set to face off against for an enjoyable 98 minutes.

Leave a comment